V63-I1-31-Fontana.Pdf (87.64Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiaroscuro in the Series of Books Titled the Art of Drawing Published by Search Press, Giovanni Civardi's Drawing Light &

Chiaroscuro In the series of books titled The Art of Drawing published by Search Press, Giovanni Civardi’s Drawing Light & Shade: Understanding Chiaroscuro discusses the application of this technique. Civardi says that “[c]hiaroscuro generally refers to the graduating tones, from light to dark, in a work of art, and the artist’s skill in using this technique to represent volume and mood” (Civardi, p. 3). Essentially, artists use chiaroscuro to show the contrast between light and dark areas in a composition “to suggest form in relation to a light source” (p. 3). The term chiaroscuro originated during the European Renaissance and artists developed the technique in various ways such as through composition, mood, and to show volume (p. 3; Harvard Art Museum glossary). For instance, chiaroscuro can be found in different kinds of art forms that include drawing, woodcuts, painting, photography, and in cinema (Hall; Landau and Parshall; Civardi). Within a compositional sense, Geertgen tot Sint Jans’s Nativity at Night (1490) is an example of establishing light sources within a painting (Earls; Hall). Ugo da Carpi, Giovanni Baglione, and Caravaggio developed the use of an unseen light source as part of the composition in their work (Earls; Hall). Caravaggio is accredited with developing the style which became known as tenebrism. This particular style stresses the intense contrast between light and dark where darkness is in prominence (Fichner-Rathus; Buser). In drawing and sketching, artists use pencil, charcoal, paint, ink, or a computer to create the effect of volume by establishing one or more light sources. In Drawing Light & Shade: Understanding Chiaroscuro, Civardi effectively explains form and cast shadow with a light source, the penumbra line “around the outer edge of the cast shadow [where] the darkness is less intense,” the shadow line, form shadow, the penumbra, cast shadow, and shadow line from the shadow cast by the object onto a surrounding surface (Civardi, pp. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

No, Not Caravaggio

2 SEPTEMBER2018 I valletta 201 a NO~ NOT CARAVAGGIO Crowds may flock to view Caravaggio's Beheading of StJohn another artist, equally talented, has an even a greater link with-Valletta -Mattia Preti. n 1613, in the small town of Taverna, in Calabria, southern Italy, a baby boy was born who would grow up to I become one of the world's greatest and most prolific artists of his time and to leave precious legacies in Valletta and the rest of Malta. He is thought to have first been apprenticed to Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, who was known as a follower and admirer of Caravaggio. His brother, Gregorio, was also a painter and painted an altarpiece for the Chapel of . the world designed and built by Preti, sometime in the 1620s Preti joined.him in the Langue of Aragon, Preti offered to do and no fewer than seven of his paintings Rome. · more wor1< on the then new and very, hang within it. They include the There he grasped Caravaggio's bareSt John's Co-Cathedral. Grand monumental titular painting and others techniques and those of other famous Master Raphael Cotoner accepted his which fit perfectly in the architecturally and popular artists of the age, including offer·and commissioned him to decorate designed stone alcoves he created for Rubens and Giovanni Lanfranco. the whole vaulted ceiling. The them. Preti spent time in Venice between 1644 magnificent scenes from the life of St In keeping with the original need for and 1646 taking the chance to observe the John took six years and completely the church, the saints in the images are all opulent Venetian styles and palettes of transformed the cathedral. -

Jusepe De Ribera and the Dissimulation of Sight

Jusepe de Ribera and the Dissimulation of Sight Paper abstract Itay Sapir, Italian Academy, Fall 2011 My overarching research program discusses seventeenth-century Central Italian painting as the site of epistemological subversion. In the Italian Academy project, the contribution of the Hispano-Neapolitan painter Jusepe/José de Ribera to the treatment of these issues will be analyzed. Early in his career, in his Roman years, Ribera was one of the most direct followers of Caravaggio; however, later on he evolved into a fully individual artistic personality, and developed further some of Caravaggio’s innovations. Most current research on Ribera concentrates on filling in the lacunae in the artist’s biography, on describing the change of style that arguably occurred around 1635 from darker, “naturalist” paintings to a more idealistic, classical style, and on discussing Ribera’s confused “national” character as a Spanish- born artist working in Spanish-ruled Naples to patrons both Spanish and Italian. My project will attempt to interpret Ribera’s art in terms of its epistemological stance on questions of sensorial perception, information transmission and opaque mimesis. Iconographical depictions of the senses are a convenient starting point, but I would like to show how Ribera’s pictorial interest in these issues can be detected even in works whose subject matter is more diverse. Some specific points of interest: Ribera’s depiction of figures’ eyes, often covered with thick shadows and thus invisible to the spectator’s gaze and complicating the visual network within the diegetic space of the work; sustained interest in sight deficiencies; and emphasis on haptic elements such as skin teXtures. -

Episode 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights

EpisodE 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights Caravaggio’s painting contains a lesson to the viewer about the transience of youth, the perils of sensual pleasure, and the precariousness of life. Questions to Consider 1. How do you react to the painting? Does your impression change after the first glance? 2. What elements of the painting give it a sense of intimacy? 3. Do you share Januszczak’s sympathies with the lizard, rather than the boy? Why or why not? Other works Featured Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607-1610), Caravaggio Young Bacchus (1593), Caravaggio The Fortune Teller (ca. 1595), Caravaggio The Cardsharps (ca. 1594), Caravaggio The Taking of Christ (1602), Caravaggio The Lute Player (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Contarelli Chapel paintings, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi: The Calling of St. Matthew, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew, The Inspiration of St. Matthew (1597-1602), Caravaggio The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1608), Caravaggio The Sacrifice of Isaac (1601-02), Caravaggio David (1609-10), Caravaggio Bacchus (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Boy with a Fruit Basket (1593), Caravaggio St. Jerome (1605-1606), Caravaggio ca. 1595-1600 (oil on canvas) National Gallery, London A Table Laden with Flowers and Fruit (ca. 1600-10), Master of the Hartford Still-Life 9 EPTAS_booklet_2_20b.indd 10-11 2/20/09 5:58:46 PM EpisodE 6 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci Highlights A robbery and attempted forgery in 1911 helped propel Mona Lisa to its position as the most famous painting in the world. Questions to Consider 1. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

“The Concert” Oil on Canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ Ins., 105.5 by 133.5 Cms

Dirck Van Baburen (Wijk bij Duurstede, near Utrecht 1594/5 - Utrecht 1624) “The Concert” Oil on canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ ins., 105.5 by 133.5 cms. Dirck van Baburen was the youngest member of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of artists all hailing from the city of Utrecht or its environs, who were inspired by the work of the famed Italian painter, Caravaggio (1571-1610). Around 1607, Van Baburen entered the studio of Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638), an important Utrecht painter who primarily specialized in portraiture. In this studio the fledgling artist probably received his first, albeit indirect, exposure to elements of Caravaggio’s style which were already trickling north during the first decade of the new century. After a four-year apprenticeship with Moreelse, Van Baburen departed for Italy shortly after 1611; he would remain there, headquartered in Rome, until roughly the summer of 1620. Caravaggio was already deceased by the time Van Baburen arrived in the eternal city. Nevertheless, his Italian period work attests to his familiarity with the celebrated master’s art. Moreover, Van Baburen was likely friendly with one of Caravaggio’s most influential devotees, the enigmatic Lombard painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622). Manfredi and Van Baburen were recorded in 1619 as living in the same parish in Rome. Manfredi’s interpretations of Caravaggio’s are profoundly affected Van Baburen as well as other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Van Baburen’s output during his Italian sojourn is comprised almost entirely of religious paintings, some of which were executed for Rome’s most prominent churches. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Mario Minniti Young Gallants

Young Gallants 1) Boy Peeling Fruit 1592 2) The Cardsharps 1594 3) Fortune-Teller 1594 4) David with the Head 5) David with the Head of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Mario Minniti 1) Fortune-Teller 1597–98 2) Calling of Saint 3) Musicians 1595 4) Lute Player 1596 Matthew 1599-00 5) Lute Player 1600 6) Boy with a Basket of 7) Boy Bitten by a Lizard 8) Boy Bitten by a Lizard Fruit 1593 1593 1600 9) Bacchus 1597-8 10) Supper at Emmaus 1601 Men-1 Cecco Boneri 1) Conversion of Saint 2) Victorious Cupid 1601-2 3) Saint Matthew and the 4) John the Baptist 1602 5) David and Goliath 1605 Paul 1600–1 Angel, 1602 6) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis, 1609 K 1) Martyrdom of Saint 2) Conversion of Saint Paul 3) Saint John the Baptist at Self portraits Matthew 1599-1600 1600-1 the Source 1608 1) Musicians 1595 2) Bacchus1593 3) Medusa 1597 4) Martyrdom of Saint Matthew 1599-1600 5) Judith Beheading 6) David and Goliath 7) David with the Head 8) David with the Head 9) Ottavia Leoni, 1621-5 Holofernes 1598 1605 of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Men 2 Women Fillide Melandroni 1) Portrait of Fillide 1598 2) Judith Beheading 3) Conversion of Mary Holoferne 1598 Magdalen 1599 4) Saint Catherine 5) Death of the 6) Magdalen in of Alexandria 1599 Virgin 1605 Ecstasy 1610 A 1) Fortune teller 1594 2) Fortune teller 1597-8 B 1) Madonna of 2) Madonna dei Loreto 1603–4 Palafrenieri 1606 Women 1 C 1) Seven Acts of Mercy 2) Holy Family 1605 3) Adoration of the 4) Nativity with Saints Lawrence 1606 Shepherds -

The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics the Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet

Nuncius 31 (2016) 288–331 brill.com/nun The Encounter of the Emblematic Tradition with Optics The Anamorphic Elephant of Simon Vouet Susana Gómez López* Faculty of Philosophy, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract In his excellent work Anamorphoses ou perspectives curieuses (1955), Baltrusaitis con- cluded the chapter on catoptric anamorphosis with an allusion to the small engraving by Hans Tröschel (1585–1628) after Simon Vouet’s drawing Eight satyrs observing an ele- phantreflectedonacylinder, the first known representation of a cylindrical anamorpho- sis made in Europe. This paper explores the Baroque intellectual and artistic context in which Vouet made his drawing, attempting to answer two central sets of questions. Firstly, why did Vouet make this image? For what purpose did he ideate such a curi- ous image? Was it commissioned or did Vouet intend to offer it to someone? And if so, to whom? A reconstruction of this story leads me to conclude that the cylindrical anamorphosis was conceived as an emblem for Prince Maurice of Savoy. Secondly, how did what was originally the project for a sophisticated emblem give rise in Paris, after the return of Vouet from Italy in 1627, to the geometrical study of catoptrical anamor- phosis? Through the study of this case, I hope to show that in early modern science the emblematic tradition was not only linked to natural history, but that insofar as it was a central feature of Baroque culture, it seeped into other branches of scientific inquiry, in this case the development of catoptrical anamorphosis. Vouet’s image is also a good example of how the visual and artistic poetics of the baroque were closely linked – to the point of being inseparable – with the scientific developments of the period. -

Artemisia Gentileschi : the Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-13-2010 Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar Deborah Anderson Silvers University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Silvers, Deborah Anderson, "Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3588 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Artemisia Gentileschi : The Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar by Deborah Anderson Silvers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Naomi Yavneh, Ph.D. Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 13, 2010 Keywords: Baroque, Susanna and the Elders, self referential Copyright © 2010, Deborah Anderson Silvers DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Fon Silvers. Nearly seven years ago, on my birthday, he told me to fulfill my long held dream of going back to school to complete a graduate degree. He promised to support me in every way that he possibly could, and to be my biggest cheerleader along the way. -

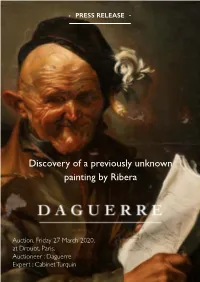

Discovery of a Previously Unknown Painting by Ribera

PRESS RELEASE Discovery of a previously unknown painting by Ribera Auction, Friday 27 March 2020, at Drouot, Paris. Auctioneer : Daguerre Expert : Cabinet Turquin Discovery of a previously unknown pain- ting by Ribera, a major 17th century artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) was only 20 years old when he painted this work, « The Mathematician ». The Spanish born artist was yet to achieve his renown as the great painter of Naples, the city considered to be one of the most important artistic centers of the 17th century. It is in Rome, before this Neapolitan period, in around 1610, that Ribera paints this sin- gular and striking allegory of Knowledge. The painting is unrecorded and was unknown to Ribera specialists. Now authenticated by Stéphane Pinta from the Cabinet Turquin, the work is to be sold at auction at Drouot on 27 March 2020 by the auction house Daguerre with an estimate of 200,000 to 300,000 Euros. 4 key facts to understand the painting 1. This discovery sheds new light on the artist’s early period that today lies at the heart of research being done on his oeuvre. 2. The painting portrays one of the artist’s favorite models, one that he placed in six other works from his Roman period. 3. In this painting, Ribera gives us one of his most surprising and colorful figures; revealing a sense of humor that was quite original for the time. 4. His experimenting with light and his choosing of a coarse and unfortunate sort of character to represent a savant echo both the chiaroscuro and the provocative art of Caravaggio.