New Light on Mattia and Gregorio Preti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christmas Cantata (2019) 2

I. Come, O Come, Emmanuel (intro) (Numbers 24:17) Words of hope sustained God’s chosen people as they awaited the promised Messiah. (Numbers 24:17) A star will come out of Jacob; a scepter will rise out of Israel. “The Creation of Adam” - Michelangelo (1512) O come, O come, Emmanuel, "The Creation of Eve” - Michelangelo (1508-1512) And ransom captive Israel, "The Fall of Adam" - Michelangelo (1508-1512) That mourns in lonely exile here "The Expulsion From Paradise" - Michelangelo (1508-1512) Until the Son of God appear. "Labors of Adam and Eve" - Alonso Cano (1650) O come, Thou Dayspring, come and cheer "Cain and Abel" - Tintoretto (1550) our spirits by Thine Advent here; "The Lamentation of Abel” Pieter Lastman (1623) and drive away the shades of night, "Cain Flees" - William Blake (1825) and pierce the clouds and bring us light! Rejoice, Rejoice! Emmanuel shall come to thee, O Israel! (interlude) "The Flood” - J.M.W. Turner (1804) The King shall come when morning dawns “God’s Promise” Joseph Anton Koch (1803) and light triumphant breaks; “ God’s Covenant with Abram” Byzantine (6th Century) When beauty gilds the eastern hills “Jacob’s Dream” Lo Spangnoletto (1639) and life to joy awakes. ”Joseph Sold into Slavery" - Damiano Mascagni (1602) The King shall come when morning dawns ”Joseph Saves Egypt" – Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1644)) and earth’s dark night is past; “Hebrews Make Bricks” Tomb (1440 BC) O haste the rising of that morn, “Burning Bush” – Sebastien Bourdon (17th cent.) the day that e’er shall last. “Crossing of the Red Sea” Come, Emmanuel; “Israelites led by Pillar of Light” – William West (1845) Come, Emmanuel; “Israelites led by Pillar of Fire” The Morning Star shall soon arise, O Come, Emmanuel. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

No, Not Caravaggio

2 SEPTEMBER2018 I valletta 201 a NO~ NOT CARAVAGGIO Crowds may flock to view Caravaggio's Beheading of StJohn another artist, equally talented, has an even a greater link with-Valletta -Mattia Preti. n 1613, in the small town of Taverna, in Calabria, southern Italy, a baby boy was born who would grow up to I become one of the world's greatest and most prolific artists of his time and to leave precious legacies in Valletta and the rest of Malta. He is thought to have first been apprenticed to Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, who was known as a follower and admirer of Caravaggio. His brother, Gregorio, was also a painter and painted an altarpiece for the Chapel of . the world designed and built by Preti, sometime in the 1620s Preti joined.him in the Langue of Aragon, Preti offered to do and no fewer than seven of his paintings Rome. · more wor1< on the then new and very, hang within it. They include the There he grasped Caravaggio's bareSt John's Co-Cathedral. Grand monumental titular painting and others techniques and those of other famous Master Raphael Cotoner accepted his which fit perfectly in the architecturally and popular artists of the age, including offer·and commissioned him to decorate designed stone alcoves he created for Rubens and Giovanni Lanfranco. the whole vaulted ceiling. The them. Preti spent time in Venice between 1644 magnificent scenes from the life of St In keeping with the original need for and 1646 taking the chance to observe the John took six years and completely the church, the saints in the images are all opulent Venetian styles and palettes of transformed the cathedral. -

Gallery Baroque Art in Italy, 1600-1700

Gallery Baroque Art in Italy, 1600-1700 The imposing space and rich color of this gallery reflect the Baroque taste for grandeur found in the Italian palaces and churches of the day. Dramatic and often monumental, this style attested to the power and prestige of the individual or institution that commissioned the works of art. Spanning the 17th century, the Baroque period was a dynamic age of invention, when many of the foundations of the modern world were laid. Scientists had new instruments at their disposal, and artists discovered new ways to interpret ancient themes. The historical and contemporary players depicted in these painted dramas exhibit a wider range of emotional and spiritual conditions. Artists developed a new regard for the depiction of space and atmosphere, color and light, and the human form. Two major stylistic trends dominated the art of this period. The first stemmed from the revolutionary naturalism of the Roman painter, Caravaggio, who succeeded in fusing intense physical observations with a profound sense of drama, achieved largely through his chiaroscuro, or use of light and shadow. The second trend was inspired by the Bolognese painter, Annibale Carracci, and his school, which aimed to temper the monumental classicism of Raphael with the optical naturalism of Titian. The expressive nature of Carracci and his followers eventually developed into the imaginative and extravagant style known as the High Baroque. The Docent Collections Handbook 2007 Edition Niccolò de Simone Flemish, active 1636-1655 in Naples Saint Sebastian, c. 1636-40 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 144 Little documentation exists regarding the career of Niccolò de Simone. -

Jusepe De Ribera and the Dissimulation of Sight

Jusepe de Ribera and the Dissimulation of Sight Paper abstract Itay Sapir, Italian Academy, Fall 2011 My overarching research program discusses seventeenth-century Central Italian painting as the site of epistemological subversion. In the Italian Academy project, the contribution of the Hispano-Neapolitan painter Jusepe/José de Ribera to the treatment of these issues will be analyzed. Early in his career, in his Roman years, Ribera was one of the most direct followers of Caravaggio; however, later on he evolved into a fully individual artistic personality, and developed further some of Caravaggio’s innovations. Most current research on Ribera concentrates on filling in the lacunae in the artist’s biography, on describing the change of style that arguably occurred around 1635 from darker, “naturalist” paintings to a more idealistic, classical style, and on discussing Ribera’s confused “national” character as a Spanish- born artist working in Spanish-ruled Naples to patrons both Spanish and Italian. My project will attempt to interpret Ribera’s art in terms of its epistemological stance on questions of sensorial perception, information transmission and opaque mimesis. Iconographical depictions of the senses are a convenient starting point, but I would like to show how Ribera’s pictorial interest in these issues can be detected even in works whose subject matter is more diverse. Some specific points of interest: Ribera’s depiction of figures’ eyes, often covered with thick shadows and thus invisible to the spectator’s gaze and complicating the visual network within the diegetic space of the work; sustained interest in sight deficiencies; and emphasis on haptic elements such as skin teXtures. -

Episode 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights

EpisodE 5 Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio Highlights Caravaggio’s painting contains a lesson to the viewer about the transience of youth, the perils of sensual pleasure, and the precariousness of life. Questions to Consider 1. How do you react to the painting? Does your impression change after the first glance? 2. What elements of the painting give it a sense of intimacy? 3. Do you share Januszczak’s sympathies with the lizard, rather than the boy? Why or why not? Other works Featured Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist (1607-1610), Caravaggio Young Bacchus (1593), Caravaggio The Fortune Teller (ca. 1595), Caravaggio The Cardsharps (ca. 1594), Caravaggio The Taking of Christ (1602), Caravaggio The Lute Player (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Contarelli Chapel paintings, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi: The Calling of St. Matthew, The Martyrdom of St. Matthew, The Inspiration of St. Matthew (1597-1602), Caravaggio The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (1608), Caravaggio The Sacrifice of Isaac (1601-02), Caravaggio David (1609-10), Caravaggio Bacchus (ca. 1596), Caravaggio Boy with a Fruit Basket (1593), Caravaggio St. Jerome (1605-1606), Caravaggio ca. 1595-1600 (oil on canvas) National Gallery, London A Table Laden with Flowers and Fruit (ca. 1600-10), Master of the Hartford Still-Life 9 EPTAS_booklet_2_20b.indd 10-11 2/20/09 5:58:46 PM EpisodE 6 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci Highlights A robbery and attempted forgery in 1911 helped propel Mona Lisa to its position as the most famous painting in the world. Questions to Consider 1. -

Colnaghistudiesjournal Journal-01

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Xavier F. Salomon Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, The Frick Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Collection, New York. Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Salvador Salort-Pons Director, President & CEO, Detroit Francesca Baldassari Art Historian. Institute of Arts. Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Research Associate in Art History, Jack Soultanian Conservator, The Metropolitan Museum of Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is Art, New York. The Open University. to publish texts on significant pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition Bruce Boucher Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Nicola Spinosa Former Director of Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. that have recently come to light or about which new research is underway, as well as Till-Holger Borchert Director, Musea Brugge. Carl Strehlke Adjunct Emeritus, Philadelphia Museum of Art. on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the Antonia Boström Keeper of Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics Holly Trusted Senior Curator of Sculpture, Victoria & Albert broader context of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. & Glass, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Museum, London. Edgar Peters Bowron Former Audrey Jones Beck Curator of Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Benjamin van Beneden Director, Rubenshuis, Antwerp. European Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Editorial Committee, composed of specialists on painting, sculpture, architecture, Mark Westgarth Programme Director and Lecturer in Art History Xavier Bray Director, The Wallace Collection, London. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

“The Concert” Oil on Canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ Ins., 105.5 by 133.5 Cms

Dirck Van Baburen (Wijk bij Duurstede, near Utrecht 1594/5 - Utrecht 1624) “The Concert” Oil on canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ ins., 105.5 by 133.5 cms. Dirck van Baburen was the youngest member of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of artists all hailing from the city of Utrecht or its environs, who were inspired by the work of the famed Italian painter, Caravaggio (1571-1610). Around 1607, Van Baburen entered the studio of Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638), an important Utrecht painter who primarily specialized in portraiture. In this studio the fledgling artist probably received his first, albeit indirect, exposure to elements of Caravaggio’s style which were already trickling north during the first decade of the new century. After a four-year apprenticeship with Moreelse, Van Baburen departed for Italy shortly after 1611; he would remain there, headquartered in Rome, until roughly the summer of 1620. Caravaggio was already deceased by the time Van Baburen arrived in the eternal city. Nevertheless, his Italian period work attests to his familiarity with the celebrated master’s art. Moreover, Van Baburen was likely friendly with one of Caravaggio’s most influential devotees, the enigmatic Lombard painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622). Manfredi and Van Baburen were recorded in 1619 as living in the same parish in Rome. Manfredi’s interpretations of Caravaggio’s are profoundly affected Van Baburen as well as other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Van Baburen’s output during his Italian sojourn is comprised almost entirely of religious paintings, some of which were executed for Rome’s most prominent churches. -

Mario Minniti Young Gallants

Young Gallants 1) Boy Peeling Fruit 1592 2) The Cardsharps 1594 3) Fortune-Teller 1594 4) David with the Head 5) David with the Head of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Mario Minniti 1) Fortune-Teller 1597–98 2) Calling of Saint 3) Musicians 1595 4) Lute Player 1596 Matthew 1599-00 5) Lute Player 1600 6) Boy with a Basket of 7) Boy Bitten by a Lizard 8) Boy Bitten by a Lizard Fruit 1593 1593 1600 9) Bacchus 1597-8 10) Supper at Emmaus 1601 Men-1 Cecco Boneri 1) Conversion of Saint 2) Victorious Cupid 1601-2 3) Saint Matthew and the 4) John the Baptist 1602 5) David and Goliath 1605 Paul 1600–1 Angel, 1602 6) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis, 1609 K 1) Martyrdom of Saint 2) Conversion of Saint Paul 3) Saint John the Baptist at Self portraits Matthew 1599-1600 1600-1 the Source 1608 1) Musicians 1595 2) Bacchus1593 3) Medusa 1597 4) Martyrdom of Saint Matthew 1599-1600 5) Judith Beheading 6) David and Goliath 7) David with the Head 8) David with the Head 9) Ottavia Leoni, 1621-5 Holofernes 1598 1605 of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Men 2 Women Fillide Melandroni 1) Portrait of Fillide 1598 2) Judith Beheading 3) Conversion of Mary Holoferne 1598 Magdalen 1599 4) Saint Catherine 5) Death of the 6) Magdalen in of Alexandria 1599 Virgin 1605 Ecstasy 1610 A 1) Fortune teller 1594 2) Fortune teller 1597-8 B 1) Madonna of 2) Madonna dei Loreto 1603–4 Palafrenieri 1606 Women 1 C 1) Seven Acts of Mercy 2) Holy Family 1605 3) Adoration of the 4) Nativity with Saints Lawrence 1606 Shepherds -

Mediterraneo in Chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer E Mattia Preti Da Malta a Roma Mostra a Cura Di Sandro Debono E Alessandro Cosma

Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma mostra a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma Roma, Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma - Palazzo Barberini 12 gennaio 2017 - 21 maggio 2017 COMUNICATO STAMPA Le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma presentano dal 12 gennaio a 21 maggio 2017 nella sede di Palazzo Barberini Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma, a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma. La mostra raccoglie alcuni capolavori della collezione del MUŻA – Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti (Heritage Malta) de La Valletta di Malta messi a confronto per la prima volta con celebri opere della collezione romana. La mostra è il primo traguardo di una serie di collaborazioni che le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma hanno avviato con i più importanti musei internazionali per valorizzare le rispettive collezioni e promuoverne la conoscenza e lo studio. In particolare l’attuale periodo di chiusura del museo maltese, per la realizzazione del nuovo ed innovativo progetto MUŻA (Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Museo Nazionale delle Arti), ha permesso di avviare un fruttuoso scambio che ha portato a Roma le opere in mostra, mentre approderanno sull’isola altrettanti dipinti provenienti dalle Gallerie Nazionali in occasione di una grande esposizione nell’ambito delle iniziative relative a Malta, capitale europea della cultura nel 2018. In mostra diciotto dipinti riprendono l’intensa relazione storica e artistica intercorsa tra l’Italia e Malta a partire dal Seicento, quando prima Caravaggio e poi Mattia Preti si trasferirono sull’isola come cavalieri dell’ordine di San Giovanni (Caravaggio dal 1606 al 1608, Preti per lunghissimi periodi dal 1661 e vi morì nel 1699), favorendo la progressiva apertura di Malta allo stile e alle novità del Barocco romano. -

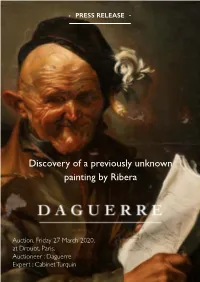

Discovery of a Previously Unknown Painting by Ribera

PRESS RELEASE Discovery of a previously unknown painting by Ribera Auction, Friday 27 March 2020, at Drouot, Paris. Auctioneer : Daguerre Expert : Cabinet Turquin Discovery of a previously unknown pain- ting by Ribera, a major 17th century artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) was only 20 years old when he painted this work, « The Mathematician ». The Spanish born artist was yet to achieve his renown as the great painter of Naples, the city considered to be one of the most important artistic centers of the 17th century. It is in Rome, before this Neapolitan period, in around 1610, that Ribera paints this sin- gular and striking allegory of Knowledge. The painting is unrecorded and was unknown to Ribera specialists. Now authenticated by Stéphane Pinta from the Cabinet Turquin, the work is to be sold at auction at Drouot on 27 March 2020 by the auction house Daguerre with an estimate of 200,000 to 300,000 Euros. 4 key facts to understand the painting 1. This discovery sheds new light on the artist’s early period that today lies at the heart of research being done on his oeuvre. 2. The painting portrays one of the artist’s favorite models, one that he placed in six other works from his Roman period. 3. In this painting, Ribera gives us one of his most surprising and colorful figures; revealing a sense of humor that was quite original for the time. 4. His experimenting with light and his choosing of a coarse and unfortunate sort of character to represent a savant echo both the chiaroscuro and the provocative art of Caravaggio.