Excavations at Abernethy Primary School, Abernethy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (Updated 22/2/2020)

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (updated 22/2/2020) Aberargie 17-1-1855: BRIDGE OF EARN. 1890 ABERNETHY RSO. Rubber 1899. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 29-11-1969. Aberdalgie 16-8-1859: PERTH. Rubber 1904. Closed 11-4-1959. ABERFELDY 1788: POST TOWN. M.O.6-12-1838. No.2 allocated 1844. 1-4-1857 DUNKELD. S.B.17-2-1862. 1865 HO / POST TOWN. T.O.1870(AHS). HO>SSO 1-4-1918 >SPSO by 1990 >PO Local 31-7-2014. Aberfoyle 1834: PP. DOUNE. By 1847 STIRLING. M.O.1-1-1858: discont.1-1-1861. MO-SB 1-8-1879. No.575 issued 1889. By 4/1893 RSO. T.O.19-11-1895(AYL). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 19-1-1921 STIRLING. Abernethy 1837: NEWBURGH,Fife. MO-SB 1-4-1875. No.434 issued 1883. 1883 S.O. T.O.2-1-1883(AHT) 1-4-1885 RSO. No.588 issued 1890. 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 30-9-2008 >Mobile. Abernyte 1854: INCHTURE. 1-4-1857 PERTH. 1861 INCHTURE. Closed 12-8-1866. Aberuthven 8-12-1851: AUCHTERARDER. Rubber 1894. T.O.1-9-1933(AAO)(discont.7-8-1943). S.B.9-9-1936. Closed by 1999. Acharn 9-3-1896: ABERFELDY. Rubber 1896. Closed by 1999. Aldclune 11-9-1883: BLAIR ATHOL. By 1892 PITLOCHRY. 1-6-1901 KILLIECRANKIE RSO. Rubber 1904. Closed 10-11-1906 (‘Auldclune’ in some PO Guides). Almondbank 8-5-1844: PERTH. Closed 19-12-1862. Re-estd.6-12-1871. MO-SB 1-5-1877. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

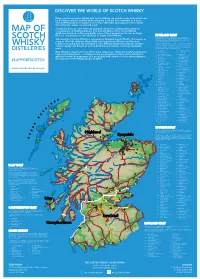

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Post Office Perth Directory

3- -6 3* ^ 3- ^<<;i'-X;"v>P ^ 3- - « ^ ^ 3- ^ ^ 3- ^ 3* -6 3* ^ I PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION 1 3- -e 3- -i 3- including I 3* ^ I KINROSS-SHIRE | 3» ^ 3- ^ I These books form part of a local collection | 3. permanently available in the Perthshire % 3' Room. They are not available for home ^ 3* •6 3* reading. In some cases extra copies are •& f available in the lending stock of the •& 3* •& I Perth and Kinross District Libraries. | 3- •* 3- ^ 3^ •* 3- -g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1878prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1878 AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ^ Jleto ^lan of the Citg ant) i^nbixons, ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY LEITCH & LESLIE. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS. I §ooksz\ltmrW'Xmm-MBy & Stationers, | ^D, SILVER, COLOUR, & HERALDIC STAMPERS, Ko. 23 Qeorqe $treet, Pepjh. An extensive Stock of BOOKS IN GENERAL LITERATURE ALWAYS KEPT IN STOCK, THE LIBRARY receives special attention, and. the Works of interest in History, Religion, Travels, Biography, and Fiction, are freely circulated. STATIONEEY of the best Englisli Mannfactura.. "We would direct particular notice to the ENGRAVING, DIE -SINKING, &c., Which are carried on within the Previises. A Large and Choice Selection of BKITISK and FOEEIGU TAEOT GOODS always on hand. gesigns 0f JEonogntm^, Ac, free nf rhitrge. ENGLISH AND FOREIGN NE^A^SPAPERS AND MAGAZINES SUPPLIED REGULARLY TO ORDER. 23 GEORGE STREET, PERTH. ... ... CONTENTS. Pag-e 1. -

Residential Development at Ayton Farm, Aberargie, Perthshire, PH2 9NE

Residential Development at Ayton Farm, Aberargie, Perthshire, PH2 9NE Abernethy - 1.5m M90 - 2m Bridge of Earn – 2.5m Perth – 4m Dundee – 24m Edinburgh – 32m Nine attractive serviced rural house plots zoned for housing and ranging from £60,000 per plot upwards located beside the River Farg and within walking distance of the Baiglie Inn. There is also a substantial farmhouse for sale which will be available at a later date. Plots 6, 7, 8 and 9 may have access to a communal 2.4 acre paddock (as can be seen in the foreground of the photo above) and these four plots overlook it. The plots are just two miles from the M90 motorway (J9) and 4 miles from Perth. For Sale as a whole (6.51 Acres) or as 9 individual serviced plots + farmhouse. Plots 1-9 have had planning applications applied for and are under consideration The sellers would consider selling the whole property with the developers carrying out the installation of mains water, mains electricity and a private sewage treatment plant but the most likely scenario would be for the sellers to sell all of the plots off as serviced plots with access roads, mains electricity, water and a private sewage treatment plant installed by them. McCrae & McCrae Limited, Chartered Surveyors, 27 East Port, Dunfermline, KY12 7JG 01383 722454, 9 Charlotte Street, Perth PH1 5LW 01738 634669, 29 York Place, Edinburgh EH1 3HP. SITUATION Ayton Farmsteading is situated to the south of Aberargie, which is located just east of the Baiglie Inn mini roundabout junction linking the A912 Glenfarg road and the A913 Perth- Abernethy-Cupar Road. -

North Ayrshire Council North Lanarkshire Council

ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE Elgin, New and Amended Roadways, Junctions Shotts, Willowind Developments (Jersey) Ltd, Methven 1241 and Bridge, A96(T) 578 Starryshaw Wind Farm 968 Milnathort 1172 Elgin 682, 839, 966, 1003, 1176, 1347, 1381, Muthill 685, 1138, 1241, 1348, 1698 1728, 2010 ORKNEY ISLANDS COUNCIL Ochtertyre 1241 Findhorn 916 Birsay 719, 2009 Perth 648, 685, 761, 919, 964, 1002, 1094, Findochty 803, 1417, 1925 Cooke Aquaculture Scotland, Salmon Farming 1138, 1241, 1289, 1417, 1490, 1530, 1568, Fochabers 1090, 2010 Site 1619 1653, 1697, 1806, 1843, 1888, 1973 Forres 1810 Eday Sound, Scottish Sea Farms Ltd, Fish Pitlochry 1094, 1417, 1697, 1785, 1806 Keith 1533 Farm Cages (Replacement for those at Noust Rattray, Blairgowrie 919 Lossiemouth 1417, 1451, 1969 Geo (Backaland) and at Kirk Taing) 881, 1725 Snaigow, Dunkeld 685, 1785, 1843, 1973 Rathven 1276, 1887 Holm 1726 Spittalfield 1047 U96E Scotsburn – New Forres Road, Stopping Hoy 1239 St Kessogs, Dalginross 1697 up of Section Order 2014 683, 1571 Kirkwall 622, 718, Trinafour 718 NORTH AYRSHIRE COUNCIL 759, 916, 1274, 1307, 1493, 1532, 1656, 1657, RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL 1764, 1807, 1844, 1926, 1969 Ardrossan 839, 841 Lyness, Cooke Aquaculture Scotland Ltd, Bishopton 580, 1454, 1807 Beith 622 Finfish Farm, Chalmers Hope 1847 Bridge of Weir 966, 1172, 1276, 1726, 1764 Brodick 580 Lyness, Hoy 1138 Hillington Park Simplified Planning Zone 804, Dalry 761, 1767 Papa Westray 1656 805, 843 Irvine, (Jail Close) (Stopping Up) Order 2013 Rousay, Orkney 1887 Howwood 1175 1590 South Ronaldsay -

BAIGLIE COURTYARD Aberargie • Perth • Perth and Kinross • PH2 9NF

BAIGLIE COURTYARD AberArgie • Perth • Perth And Kinross • Ph2 9nF BAIGLIE COURTYARD AberArgie • Perth Perth And Kinross • Ph2 9nF A charming family home in a rural yet accessible location Bridge of Earn 1.8 miles, Perth 6.5 miles, Edinburgh 40 miles (all distances are approximate) = Kitchen, dining room, drawing room, breakfast room, study and utility room. Five bedrooms (1 en suite) and family bathroom Garden, driveway and garage EPC Rating = D Savills Perth Solicitors Earn House Shepherd & Wedderburn Broxden Business Park 1 Exchange Crescent Lamberkine Drive Conference Square Perth PH1 1RA Edinburgh [email protected] EH3 8UL Tel: 01738 445588 0131 228 9900 VIEWING Strictly by appointment with Savills – 01738 477525. DIRECTIONS From Bridge of Earn follow the A912 (towards Abernethy) for about 1.8 miles. Just before the roundabout at Aberargie take a right turn signposted to Dron. After about 380 yards, Baiglie Courtyard is on the right. SITUATION Baiglie Courtyard is located on a quiet country lane surrounded by rolling farmland. Although rural, the property is not isolated, having Baiglie Farmhouse as its neighbour and being only a few miles from local services at Bridge of Earn, which has a post office, general store, chemist and a primary school. Perthshire is considered to be one of the most desirable counties in which to live, and Perth (6.5 miles) has an excellent range of shops, professional services and leisure facilities. ‘The Fair City’ also has a concert hall, several art galleries and a race course. Bridge of Earn links directly onto the M90 and Edinburgh is about 40 miles away. -

The Post Office Perth Directory, for ... : with a Copious Appendix, Containing

GARVIE & SYME, (LATE JOHN ROY), 42 & 79 HIGH STREET, PERTH, HAVE ALWAYS A LARGE STOCK OF HOUSE FURNISHING AND GENERAL IRONMONGERY, (Btoro-gilber plate attb Jtiriul--§ilt)cr daroius, BUILDERS' AND CABINETMAKERS' FURNISHINGS, WASHING MACHINES, PATENT MANGLES AND WRINGING MACHINES, EDGE TOOLS OF EVERY DESCRIPTION, WIEE NETTING, FENCING WIKE, EOOFING FELT, LAMPS, OILS, &c. SHOWROOMS AND WAREHOUSES— 42 and 79 HIGH STREET, PERTH. GEORGE GRIEVE, WHOLESALE AND RETAIL JEWELLER MAGIC LANTERNS. LANTERN SLIDES. The new Improved Lantern, with An extensive variety of the finest Patent Refulgent Lamp for burn- Transparencies, including the ing Paraffin Oil, is now the best, Russo-Turkish War, Palestine, most compact, and easily manipu- Egypt, Continental Cities, Ameri- lated Lantern made. Price £4 4/- ca, Sights of London, Highlands Toy Lanterns & Slides, from 4/- of Scotland, Set of Brown and the Mouse, Trial of Sir Jaspar, copies On Hire — Lantern, Slides, and of Works of Art, &c. Screen. Exhibitions conducted with the Oxy-Hydrogen Light. Catalogues on application. STERLING SILVER NICKEL-SILVER ELECTRO-SSLVER Teaspoons, 1/-, 1/3, 1/6' BROOCHES— 1/9, 2/- half-doz. PLATE Dessert Spoons & Forks, Tea and Marmalade Over 80 Varieties. 3/-> 3/6, 4/3 half-doz. Spoons ; Dessert and Table Spoons & Forks, Table Spoons and Forks Earrings, Links, ; 3/6, 4/-, 5/6, 6/- half- Honey and Jelly Dishes; Studs, Pins, Lockets, doz. Breakfast and Dinner Salt, - Necklets, Thimbles, Mustard, & Caddy Cruets ; Toast Racks, Spoons all warranted Biscuit-Boxes, Smelling-Bottles. — &c. &c, to retain their colour. in all qualities. SUNDRIES. SUNDRIES. Britannia-Metal Teapots, Table- Gold Wedding, Keeper, and Spoons, Soup-Ladles, Dish Co- Gem Rings ; Gold Studs, Links, Pins, vers ; Spectacles, Eye Glasses, Albeits, Guards ; Writing Desks, Opera Glasses, Model Engines, Work Boxes, Tea Caddies, Ink Microscopes ; Theobald & Co.'s Stands, Leather Hand-Bags, Pur- Scientific Amusements ; Table and ses and Pocket-Books ; Combs, Parlour Games : O'Bryen & Dyer's Brushes, Perfumery, &c. -

![Landscape ? 2 +%, 7C E ?K\A]` (- 2.2 Why Is Landscape Important to Us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7C E \E^ 7C E 1Cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (Llas) 3 +%](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1205/landscape-2-7c-e-k-a-2-2-why-is-landscape-important-to-us-2-ad-z-7c-e-e-7c-e-1cdfe-2-3-local-landscape-areas-llas-3-2451205.webp)

Landscape ? 2 +%, 7C E ?K\A]` (- 2.2 Why Is Landscape Important to Us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7C E \E^ 7C E 1Cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (Llas) 3 +%

Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 +%* Ajh\j` B\n (' 2 BACKGROUND 2 +%+ 2_e Dh\]ba_ (* 2.1 What is landscape ? 2 +%, 7c_e ?k\a]` (- 2.2 Why is landscape important to us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7c_e \e^ 7c_e 1cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (LLAs) 3 +%. Cgg_h Ajh\j`_\he )) 3 POLICY CONTEXT 4 +%/ Aa^c\m 8acci ), 3.1 European Landscape Convention 4 +%'& =]`ac 8acci )/ 3.2 National landscape policy 4 +%'' ;f]` ;_l_e \e^ ;fdfe^ 8acci *( 3.3 Strategic Development Plan 5 6 WILD LAND AREAS 45 3.4 Local Development Plan 5 Wild Land Areas and LLAs map 46 4 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 7 7 SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING STATEMENTS 47 5 GUIDELINES FOR THE LLAs 9 . =2:53B9D5A *. Purpose of designation 9 9 MONITORING 49 Structure of Local Landscape Areas information 9 Local Landscape Areas map 11 1>>5<4935A +& +%' @\eef]` 6fh_ij '( * 9`]Z[PLY @LYO^NL[P 7ZYaPY_TZY OPlYT_TZY^ .) +%( ;f]` ;nfe \e^ ;f]` \e 4\ad` '+ 2 Landscape Character Units 51 +%) ;f]` B\n '. Landscape Supplementary Guidance 2020 INTRODUCTION 1 TST^ F`[[WPXPY_L]d ;`TOLYNP bL^ l]^_ []ZO`NPO _Z TYNZ][Z]L_P :ZWWZbTYR ZY Q]ZX _ST^ @H7 TOPY_TlPO L ^P_ ZQ []Z[Z^PO @ZNLW the review and update of Local Landscape Designations in Perth Landscape Designations (previously Special Landscape Areas) LYO ?TY]Z^^ TY_Z _SP 7Z`YNTWk^ [WLYYTYR [ZWTNd Q]LXPbZ]V TY +)*.( for consultation. This was done through a robust methodology GSP []PaTZ`^ OP^TRYL_TZY^ L]Z`YO DP]_S bP]P XLOP TY _SP *21)^ _SL_ TYaZWaPO L OP^V'ML^PO ^_`Od& L lPWO ^`]aPd LYO ^_LRP^ and were designated with a less rigorous methodology than is now ZQ ]PlYPXPY_( =Y LOOT_TZY _SP @@8E TOPY_TlPO XPL^`]P^ _Z available. -

Environment and Infrastructure Committee 5 September 2018

PERTH AND KINROSS COUNCIL ENVIRONMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE 5 SEPTEMBER 2018 ENVIRONMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE Minute of meeting of the Environment and Infrastructure Committee held in the Council Chamber, 2 High Street, Perth on 5 September 2018 at 10.00am. Present: Councillors A Forbes, A Bailey, K Baird, M Barnacle, S Donaldson, D Doogan (up to and including Art. 485), J Duff, A Jarvis, G Laing, R McCall, A Parrott, C Reid, W Robertson, L Simpson and M Williamson. In Attendance: B Renton, Executive Director (Housing and Environment); K Reid, Chief Executive; A Clegg, S D’All, C Haggart, S Laing (up to and including Art. 481), D Littlejohn, P Marshall, F Patterson (up to and including Art. 481), P Pease (up to and including Art. 481), S Perfett, B Reekie, K Spalding (up to and including Art. 481), K Steven (up to and including Art. 483) and W Young (all Housing and Environment) C Flynn and K Molley (both Corporate and Democratic Services). Councillor A Forbes, Convener, Presiding. 477. WELCOME AND APOLOGIES The Convener welcomed everyone to the meeting and gave a special welcome to K Baird as it was her first meeting committee meeting as Vice-Convener. 478. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST In terms of the Councillors’ Code of Conduct, Councillor K Baird declared a non-financial interest in Art. 482 (Community Green Space – Working with Communities) and Art. 486 (Perth and Kinross Outdoor Access Forum Annual Report 2017-18). 479. BURIAL AND CREMATION FEES The Convener provided an update to Committee on the decision taken at the last meeting (Art. -

Inventory Acc.4796 Fettercairn Papers

Acc.4796 January 2014 Inventory Acc.4796 Fettercairn Papers National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland The Fettercairn Papers, including personal, and financial correspondence and papers, estate papers and charters, and a large series of architectural plans and drawings, of the family of Forbes and Stuart Forbes of Fettercairn and Pitsligo, 1447 – 20th cent. Deposited, 1969, by the late Mrs.P.G.C. Somervell Summary of arrangement of the collection: 1. Correspondence of Sir William Forbes, 5th Bart., of Fettercairn & Pitsligo 2-32. General Correspondence of Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart. 33-48. Special Correspondence of Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart. 1. Letters to and from Sir William Forbes, 5th Bart, 1712 c.1743 2. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1761-63, 1766-74 3. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1775-77 4. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1778-79 5. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1780 6. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1781-April 1782 7. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, May-December 1782 8. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1783 9. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1784 10. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, January-June 1785 11. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, July-December 1785 12. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, 1786 13. Letters to Sir William Forbes, 6th Bart, January-August 1787 14a. -

Parishes and Congregations: Names No Longer in Use

S E C T I O N 9 A Parishes and Congregations: names no longer in use The following list updates and corrects the ‘Index of Discontinued Parish and Congregational Names’ in the previous online section of the Year Book. As before, it lists the parishes of the Church of Scotland and the congregations of the United Presbyterian Church (and its constituent denominations), the Free Church (1843–1900) and the United Free Church (1900–29) whose names have completely disappeared, largely as a consequence of union. This list is not intended to be ‘a comprehensive guide to readjustment in the Church of Scotland’. Its purpose is to assist those who are trying to identify the present-day successor of a former parish or congregation whose name is now wholly out of use and which can therefore no longer be easily traced. Where the former name has not disappeared completely, and the whereabouts of the former parish or congregation may therefore be easily established by reference to the name of some existing parish, the former name has not been included in this list. Present-day names, in the right-hand column of this list, may be found in the ‘Index of Parishes and Places’ near the end of the book. The following examples will illustrate some of the criteria used to determine whether a name should be included or not: • Where all the former congregations in a town have been united into one, as in the case of Melrose or Selkirk, the names of these former congregations have not been included; but in the case of towns with more than one congregation, such as Galashiels or Hawick, the names of the various constituent congregations are listed.