Empire and the Dispositif of Queerness Robert Nichols, University of Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homonationalism As Assemblagejindal Global Law Review 23 Volume 4, Issue 2, November 2013

2013 / Homonationalism As AssemblageJINDAL GLOBAL LAW REVIEW 23 VOLUME 4, ISSUE 2, NOVEMBER 2013 Homonationalism As Assemblage: Viral Travels, Affective Sexualities Jasbir K. Puar* In this article I aim to contextualise the rise of gay and lesbian movements within the purview of debates about rights discourses and the rights-based subject, arguably the most potent aphrodisiac of liberalism. I examine how sexuality has become a crucial formation in the articulation of proper citizens across registers like gender, class, and race, both nationally and transnationally. The essay clarifies homonationalism as an analytic category necessary for understanding and historicising why a nation’s status as “gay-friendly” has become desirable in the first place. Like modernity, homonationalism can be resisted and resignified, but not opted out of: we are all conditioned by it and through it. The article proceeds in three sections. I begin with an overview of the project of Terrorist Assemblages, with specific attention to the circulation of the term ‘homonationalism’. Second, I will elaborate on homonationalism in the context of Palestine/Israel to demonstrate the relevance of sexual rights discourses and the narrative of ‘pinkwashing’ to the occupation. I will conclude with some rumination about the potential of thinking sexuality not as an identity, but as assemblages of sensations, affects, and forces. This virality of sexuality productively destabilises humanist notions of the subjects of sexuality but also the political organising seeking to resist -

Monster, Terrorist, Fag: the War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots

Monster, Terrorist, Fag: The War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots Jasbir K. Puar, Amit Rai Social Text, 72 (Volume 20, Number 3), Fall 2002, pp. 117-148 (Article) Published by Duke University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/31948 Access provided by Duke University Libraries (30 Jan 2017 16:08 GMT) Monster, Terrorist, Fag: The War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots How are gender and sexuality central to the current “war on terrorism”? Jasbir K. Puar This question opens on to others: How are the technologies that are being and developed to combat “terrorism” departures from or transformations of Amit S. Rai older technologies of heteronormativity, white supremacy, and national- ism? In what way do contemporary counterterrorism practices deploy these technologies, and how do these practices and technologies become the quotidian framework through which we are obliged to struggle, sur- vive, and resist? Sexuality is central to the creation of a certain knowledge of terrorism, specifically that branch of strategic analysis that has entered the academic mainstream as “terrorism studies.” This knowledge has a history that ties the image of the modern terrorist to a much older figure, the racial and sexual monsters of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Further, the construction of the pathologized psyche of the terrorist- monster enables the practices of normalization, which in today’s context often means an aggressive heterosexual patriotism. As opposed to initial post–September 11 reactions, which focused narrowly on “the disappearance of women,” we consider the question of gender justice and queer politics through broader frames of reference, all with multiple genealogies—indeed, as we hope to show, gender and sex- uality produce both hypervisible icons and the ghosts that haunt the machines of war. -

Final Complete Dissertation Robertson

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Un-Settling Questions: The Construction of Indigeneity and Violence Against Native Women A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies by Kimberly Dawn Robertson 2012 © Copyright by Kimberly Dawn Robertson 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Un-Settling Questions: The Construction of Indigeneity and Violence Against Native Women by Kimberly Dawn Robertson Doctor of Philosophy in Women’s Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Mishuana R. Goeman, Co-chair Professor Andrea Lee Smith, Co-chair There is growing recognition that violent crime victimization is pervasive in the lives of Native women, impacts the sovereignty of Native nations, and destroys Native communities. Numerous scholars, activists, and politicians have considered Congress’ findings that violent crimes committed against Native women are more prevalent than for all other populations in the United States. Unfortunately, however, relatively all of the attention given to this topic focuses on reservation or near-reservation communities despite the fact that at least 60% of Native peoples now reside in urban areas. In Un-Settling Questions: The Construction of Indigeneity and Violence Against Native Women, I posit that this oversight is intimately connected to the ii ways in which urban indigeneity has been and continues to be constructed, marginalized, and excluded by the settler state and Native peoples. Thus, heavily informed by Native feminisms, critical ethnic studies, and indigenous epistemologies, Un-Settling Questions addresses settler colonial framings of violence against Native women by decentering hegemonic narratives that position “reservation Indians” as the primary victims and perpetrators of said violence while centering an exploration of urban indigeneity in relation to this topic. -

Feminist Biopolitics and Cultural Practice Winter 2015, MA, 4 Credits Time and Place TBA

Course Syllabus (Draft) Feminist Biopolitics and Cultural Practice Winter 2015, MA, 4 Credits Time and Place TBA Hyaesin Yoon Email: [email protected] Office: Zrynyi 14, 510A Office Hours: TBA What do memorial displays for those who died from AIDS tell us about public mourning as a political measure of (disavowed) sexuality? How does the performance of dancers with disabilities challenge the normative understanding of gendered and racialized desire/desirability? How do literature and film afford space for re-imagining the relationship between women and other female animals in the circuits of biotechnology? This course examines how the biopolitical operations of gender, sexuality, race, species, and disability im/materialize through various forms of cultural practice. In this course, we will enter the conversation between feminist and queer theories and the discourse of biopolitics concerning the relationship of life (and death) to the political. We will pay particular attention to the entwinement between the biological, technological, and cultural as an important constituent of biopolitics, as most dramatically shown in – but not limited to – the emergence of bioarts and biomedia. From this perspective, the course explores a number of sites of cultural practice including digital archive, exhibit, dance, tattoo, biometrics, prosthetics, and graphic medicine as topoi of feminist criticisms and creative interventions. Learning Outcomes • Students will familiarize themselves with the major concepts and arguments in biopolitical theories, and their connections to and implications for gender studies in particular and critical theories in general. • Students will better understand and be able to analyze some of the important ways in which biopolitical power relations substantiate and operate through cultural practices in the contemporary world. -

Heteronormativity, Homonormalization, and the Subaltern Queer Subject Sebastián Granda Henao1

Heteronormativity, Homonormalization, and the Subaltern Queer Subject Sebastián Granda Henao1 Abstract: Norms are a constitutive part of the social world and political imaginaries. Without norms and rules of behavior, politics would be nonsensical, a nowhere. But then, what about norms and normativity over the individual, sexual and gendered bodies? What place is left for sexual identities, affective orientations, and diverse existences themselves when social norms dictate over non-normatively gendered people? Moreover, how about marginals from the acceptable abnormals, namely queer subaltern subjects? In this paper I intend to, first, draw a short review on what feminist and queer theory has to say about social norms regarding sex and gender – precisely on the matters of heteronormativity and homonormativity, so I can explore the trouble that such norms may produce. Second, I point out to the larger trouble that third world queers, as subaltern subjects –acknowledging queer itself is a subaltern category- may experience in their non-conformity to the double categories of being, on the one hand, gender abnormals, and on the other, by not fully compelling to the dominant Western modern, capitalist life experience. Finally, I conclude by putting in relation the discussion of gender in International Relations and the problem of heteronormativity and homonormalization of subaltern queer subjects. Key Words: Homonormativity, Queer Theory, Subaltern Subject. Heteronormatividade, Homonormalização, e o Sujeito Subalterno Queer Sebastián Granda -

Reading List 1: Feminist Theories/ Interdisciplinary Methods Chair: Liz Montegary I Am Interested in the Ways in Which Political

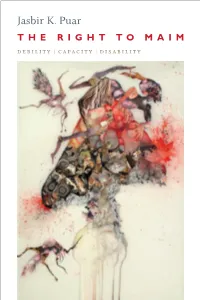

Reading List 1: Feminist theories/ Interdisciplinary methods Chair: Liz Montegary I am interested in the ways in which political and social categories get constructed through, and onto, the body. And in turn, the way bodies themselves are not fixed or given, but are constantly shaped and altered through material and political means. Biopower is central to this inquiry, as is feminist theories of gender, sex, race, and dis/ability. To me, this is both material and discursive, and I honestly question the distinction between the two. For this list, I am thinking through ways in which bodies get inscribed with meaning, measured, and surveyed, as well as the ways in which they are literally shaped by these same institutions which discipline, order, and attempt to optimize them. The idea of what is to be desired or “optimized” in a body is particularly important in thinking about sports - by that I mean that the ways in which disciplining the body is also about trying to enhance it. Biopower and Bodies Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality Volume I, 1978 Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeus Viscus, 2014 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990 Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex,’ 1993 Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism, 1994 Dean Spade, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics and the Limits of Law, 2011 Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention **Jasbir Puar, Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability, 2017 Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages, 2007 Eugenics History Jennifer Terry, An American Obsession Julian Carter, The Heart of Whiteness Stein, Melissa N. Measuring Manhood: Race and the Science of Masculinity, 1830–1934, 2015 Snorton, C. -

Jasbir K. Puar the RIGHT to MAIM Debility | Capacity | Disability PRAISE for the RIGHT to MAIM

Jasbir K. Puar THE RIGHT TO MAIM debility | capacity | disability PRAISE FOR THE RIGHT TO MAIM “ Jasbir K. Puar’s must-read book The Right to Maim revolutionizes the study of twenty-first-century war and biomedicine, offering a searingly impres- sive reconceptualization of disability, trans, and queer politics. Bringing to- gether Middle East studies and American studies, global political economy and gendered conflict studies, this book’s exciting power is its revelation of the incipient hegemony of maiming regimes. Puar’s shattering conclusions draw upon rigorous and systematic empirical analysis, ultimately offering an enthralling vision for how to disarticulate disability politics from this maiming regime’s dark power.” — paul amar, author of The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics, and the End of Neoliberalism “I n signature style, Jasbir K. Puar takes readers across multiple social and textual terrains in order to demonstrate the paradoxical embrace of the politics of disability in liberal biopolitics. Puar argues that even as liberal- ism expands its care for the disabled, it increasingly debilitates workers, subalterns, and others who find themselves at the wrong end of neoliberal- ism. Rather than simply celebrating the progressive politics of disability, trans identity, and gay youth health movements, The Right to Maim shows how each is a complex interchange of the volatile politics of precarity in contemporary biopower.” — elizabeth a. povinelli, author of Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism The Right to Maim ANIMA A SERIES EDITED BY MEL Y. CHEN AND JASBIR K. PUAR The Right to Maim Debility, Capacity, Disability jasbir k. puar Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press. -

ON BIOPOLITICS in QUEER THEORY I Am Entering This, and Any

Jasmine Rault ON BIOPOLITICS IN QUEER THEORY I am entering this, and any, conversation about Foucault from the angle of feminist queer theory – as well as the over- whelmingly Anglo-North American angle from which queer theory has been largely generated – and so I want to talk a little today about how his work influenced and continues to inform this field. Certainly from the time that queer theory was con- solidating into what would become known as a field, Foucault was central.1 In 1990 Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick published Epistemology of the Closet and Judith Butler published Gender Trouble which, along with Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands, pub- lished three years earlier, have become grounding texts in the early canon of queer theory2 – texts which each engage from different places the relationship between sex and biopower. Indeed, these early works might be the best way to introduce what becomes a sort of cleavage in queer theory’s engagement with Foucault – between a focus on the productive effects of power in the emergence and regulation of the category of ‘sex’ and ‘sexual identity’ and, on the other hand, a focus on the production and regulation of populations, race and state rac- ism. In Gender Trouble Butler asked us to recognize that power produced the apparent stability or originality of sex through a deployment of disciplinary norms of hetero-gender, but in what might be cast as a departure from Foucault, Butler leaned on Freudian psychoanalysis to thematize the sort of agential (though mostly unconscious) subversion of power effected through the redeployment, denaturalization and rematerializa- 97 On Biopolitics in Queer Theory tion of these norms – in an effort to disrupt the ease with which gay death was being accepted and administered by the state. -

Jasbir K Puar

JASBIR K PUAR Women’s & Gender Studies Rutgers University 162 Ryders Lane, Douglass Campus New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901 Education: 1999 Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, Department of Ethnic Studies. Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Dissertation: "Transnational Sexualities and Trinidad: Modern Bodies, National Queers." 1994 M.A. University of York, England, Women’s Studies. Thesis: "Identity, Racism, and Culture: Second Generation Sikh Women and Oppositionally Active Whiteness." (Distinction Awarded) 1989 B.A. Rutgers University, Economics and German. Current Appointment: 2017- Full Professor, Women’s and Gender Studies, Rutgers University 2014- Graduate Program Director, Women’s and Gender Studies Other Professional Appointments: 2007-17 Associate Professor, Women’s and Gender Studies Department, Rutgers University. 2014 Visiting Professor, Linkoping University, Sweden, April-May. 2012-13 Edward Said Chair of American Studies, American University of Beirut 2011 Visiting Fellow, Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Berlin, Germany, May-June. 2009 Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Performance Studies, New York University, Spring. 2000-07 Assistant Professor, Women’s and Gender Studies, Rutgers University. 2006 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Performance Studies, New York University, Fall. ACADEMIC HONORS Awards: Jasbir Kaur Puar 2016 Modern Languages Association GL/Q Caucus Crompton-Noll Award for Best Essay in Lesbian and Gay Studies Northeastern Association of Graduate Schools Teaching Award (Doctorate Level) 2013 Modern Languages Association GL/Q Caucus Michael Lynch Service Award Robert Sutherland Visitorship Award, Queens University 2011 Excellence in Graduate Teaching Award, The Graduate School, Rutgers University. 2007 Association for Asian American Studies Cultural Studies Book Award for Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. -

Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times

Queering the Problem TERRY GOLDIE Jasbir K. Puar. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Duke Univer- sity Press, 2007. 368 pp. he intention of this book is obvious and quite simple. Terrorist Assemblages con- Tfronts the American tendency post-9/11 to see terrorists under every bed and often in every bed. Jasbir Puar attacks the racist underpinnings of counter-terrorism, the heteronormativity of American “ethnic” groups who try to assert that they are not terrorists, and the homonormativity of gay and lesbian groups who try to assert that they are just as proudly American as anyone else who hates terrorists. Th e intention is simple and yet the book itself is extremely complex. One reason for this is suggested by the title. Th e idea of the assemblage comes from Deleuze. Argu- ably, the politics of the book are more informed by Foucault’s theories of power and knowledge, but the mode of the book is Deleuzian. A good example is the following section of the preface: Th e strategy of encouraging subjects of study to appear in all their queernesses, rather than primarily to queer the subjects of study, provides a subject-driven temporality in tandem with a method-driven temporality. Playing on this diff er- ence, between the subject being queered and queerness already existing within the subject (and thus dissipating the subject as such), allows for both the tempo- rality of being (ontological essence of the subject) and the temporality of always- becoming (continual ontological emergence, a Deleuzian becoming without be- ing) (xxiv). Many queer theorists are enamored of Deleuze. -

Bodies with New Organs Becoming Trans, Becoming Disabled

Social Text Bodies with New Organs Becoming Trans, Becoming Disabled Jasbir K. Puar “Transgender rights are the civil rights issue of our time.” So stated Vice President Joe Biden just one week before the November 2012 election. Months earlier President Barack Obama had publicly declared his sup- port for gay marriage, sending mainstream LGBT organizations and queer liberals into a tizzy. Though an unexpected comment for an elec- tion season, and nearly inaudibly rendered during a conversation with a concerned mother of Miss Trans New England, Biden’s remark,1 encoded in the rhetoric of recognition, seemed logical from a now well- established civil rights – era teleology:2 first the folks of color, then the homosexuals, now the trans folk.3 What happens to conventional understandings of “women’s rights” in this telos? Moreover, the “transgender question” puts into crisis the framing of women’s rights as human rights by pushing further the rela- tionships between gender normativity and access to rights and citizenship. I could note, as many have, that failing an intersectional analysis of these movements, we are indeed left with a very partial portrait of who benefits and how from this according of rights, not to mention their tactical invo- cation within this period of liberalism whereby, as Beth Povinelli argues, “potentiality has been domesticated.”4 As Jin Haritaworn and C. Riley Snorton argue, “It is necessary to interrogate how the uneven institution- alization of women’s, gay, and trans politics produces a transnormative subject, whose universal trajectory of coming out/transition, visibility, rec- ognition, protection, and self- actualization largely remain uninterrogated in its complicities and convergences with biomedical, neoliberal, racist, and imperialist projects.”5 In relation to this uneven institutionalization, Hari- taworn and Snorton go on to say that trans of color positions are “barely Social Text 124 • Vol. -

Review: Transnational Queer Theory and Unfolding Terrorisms Robert Diaz Wayne State University, [email protected]

Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState English Faculty Research Publications English 1-1-2008 Review: Transnational Queer Theory and Unfolding Terrorisms Robert Diaz Wayne State University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Diaz, R. (2008). Transnational Queer Theory and Unfolding Terrorisms. Criticism, 50(3), 533-541. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/englishfrp/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the English at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. TRANSNATIONAL Queer theory has always been at- tentive to often undertheorized re- QUEER THEORY lations between sexuality and cultural AND UNFOLDING citizenship. Recently, much of the TERRORISMS most exciting queer scholarship has Robert Diaz directed its attention toward an analysis of spaces outside of the United States and beyond the West, Terrorist Assemblages: Homona- focusing in particular on transna- tionalism in Queer Times by Jasbir tional communities affected by K. Puar. Durham: Duke University ever-expanding global capital and Press, 2007. Pp. 368. $89.95 cloth, imperialism. In an issue of Social Text $24.95 paper. (“What’s Queer about Queer Stud- ies Now?”), the editors suggest that a reinvigorated queer framework “insists on a broadened consideration of the late-twentieth-century global crises that have configured his- torical relations among political economies, the geopolitics of war and terror, and national manifesta- tions of sexual, racial, and gendered hierarchies.”1 In other words, a re- newed queer theoretical frame must thoroughly adapt to and expand upon the specifi c ways in which counterterrorism, mass consumer- ist culture, and battles for legal rec- ognition have compartmentalized nonnormative populations.