Cutting, Driving, Digging, and Harvesting: Re-Masculinizing the Working-Class Heroic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelle Bench Avid Editor

Michelle Bench Avid Editor Profile Michelle is a passionate editor and her technical knowledge is first-class - she has a thorough understanding of all aspects of the editing process. She was previously employed by facilities house M2 where she capably worked on some of their highest profile programmes and with the most demanding of clients. She has a natural talent in constructing and helping develop narratives. Michelle is incredibly hardworking and enthusiastic and along with her easy going friendly personality, she is a real asset to a production. Offline Credits – Entertainment “Pioneer Woman” 9 x 30min. Top rating cooking, documentary and reality series shot on a ranch in Pawhuska, Oklahoma with blogger Ree Drummond and her family. Otherwise known as the 'Pioneer Woman', Ree is a mother, wife and cook. The award-winning blogger and best-selling cookbook author comes to Food Network and shares her special brand of home cooking, from throw together suppers to elegant celebrations. Pacific Productions for Food Network “Barefoot Contessa” Ina Garten prepares a simple multi-course meal, usually for her close friends, colleagues or husband. Her recipes often include fresh herbs, which she 'hand- harvests' from her backyard garden. The show's title comes from the Italian word for countess and was originally used by Ina Garten in her best-selling cookbook. Pacific Productions for Food Network “13 Moments that Killed Michael Jackson” 1 x 90min. 3 part documentary series. This takes a look at the extraordinary life, and tragic death, of one of the world’s best loved entertainers. Counting down the fateful episodes that changed his life, this programme will explore the heartache behind the triumph, and the lows behind the highs in the life of a music icon. -

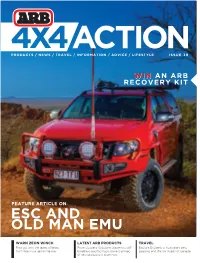

ESC and Old Man Emu

AI CT ON PRODUCTS / NEWS / TRAVEL / INFORMATION / ADVICE / LIFESTYLE ISS9 UE 3 W IN AN ARB RECOVERY KIT FEATURE ARTICLE ON ESC AND OLD MAN EMU WARN ZEON WINCH LATEST ARB PRODUCTS TRAVEL Find out why the latest offering From Outback Solutions drawers to diff Explore El Questro, Australia’s best from Warn is a game changer breathers and flip flops, there is a heap beaches and the Ice Roads of Canada of new products in store now CONTENTS PRODUCTS COMPETITIONS & PROMOTIONS 4 ARB Intensity LED Driving Light Covers 5 Win An ARB Back Pack 16 Old Man Emu & ESC Compatibility 12 ARB Roof Rack With Free 23 ARB Differential Breather Kit Awning Promotion 26 ARB Deluxe Bull Bar for Jeep WK2 24 Win an ARB Recovery Kit Grand Cherokee 83 On The Track Photo Competition 27 ARB Full Extension Fridge Slide 32 Warn Zeon Winch 44 Redarc In-Vehicle Chargers 45 ARB Cab Roof Racks For Isuzu D-Max REGULARS & Holden Colorado 52 Outback Solutions Drawers 14 Driving Tips & Techniques 54 Latest Hayman Reese Products 21 Subscribe To ARB 60 Tyrepliers 46 ARB Kids 61 Bushranger Max Air III Compressor 50 Behind The Shot 66 Latest Thule Accessories 62 Photography How To 74 Hema HN7 Navigator 82 ARB 24V Twin Motor Portable Compressor ARB 4X4 ACTION Is AlsO AvAIlABlE As A TRAVEL & EVENTS FREE APP ON YOUR IPAD OR ANDROID TABLET. 6 Life’s A Beach, QLD BACk IssuEs CAN AlsO BE 25 Rough Stuff, Australia dOwNlOAdEd fOR fREE. 28 Ice Road, Canada 38 Water For Africa, Tanzania 56 The Eastern Kimberley, WA Editor: Kelly Teitzel 68 Emigrant Trail, USA Contributors: Andrew Bellamy, Sam Boden, Pat Callinan, Cassandra Carbone, Chris Collard, Ken Duncan, Michael Ellem, Steve Fraser, Matt 76 ARB Eldee Easter 4WD Event, NSW Frost, Rebecca Goulding, Ron Moon, Viv Moon, Mark de Prinse, Carlisle 78 Gunbarrel Hwy, WA Rogers, Steve Sampson, Luke Watson, Jessica Vigar. -

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of August 29-September 4, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, AUGUST 28, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of August 29-September 4, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT AUGUST 29, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel “At- The Lawrence Welk Doc Martin “The Keeping As Time Father Brown Violet No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Brit- Globe Trekker Influ- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd lanta Homecoming” Show “You’re Never Admirer” Louisa has a Up Goes hopes to prove her in- mum “Jami Lynn” The Avett Brothers and ish songwriter Richard ence of Sicilian cuisine. KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden Inspirational songs. Too Young” rival. Å By Å nocence. Å Nickel Creek. Thompson. (In Stereo) KTIV $ 4 $ Horse Racing Estate News News 4 Insider American Ninja Warrior “Military Finals” Hannibal (In Stereo) News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Horse Racing Travers Stakes and Sword Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big American Ninja Warrior “Military Finals” Hannibal Will hopes to KDLT Saturday Night Live Taraji P. The Simp- NBC Pri- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Dancer Invitational. From Saratoga Race gram Nightly News Bang Obstacles include Doorknob Arch. (In Stereo) slay Francis Dolarhyde. News Henson; Mumford & Sons. (In sons metime News Å KDLT % 5 % Course in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. -

Ice Road Truckers Needn't Fret

Western Canada’s Trucking Newspaper Since 1989 December 2016 Volume 27, Issue 12 Rock slide: B.C. rock slide Helping truckers: Truckers STA gala: Saskatchewan RETAIL wipes out section of Trans- Christmas Group looks for Trucking Association holds ADVERTISING Canada Highway, costs donations to help trucking annual gala, addresses Page 13 Page 16 Page Page 12 Page industry thousands. families. industry issues. PAGES 29-39 truckwest.ca Safety on winter roads Winter driving conditions can pose challenge to even the biggest rig By Derek Clouthier Many believe that the use of airships, like the one depicted above, to deliver cargo to Canada’s northern region would bring REGINA, Sask. – Don’t be fooled by the business to the trucking industry. balmy mid-November temperatures that hit Western Canada this year – win- ter is just around the corner. And whether you’re trucking through mountainous terrain in British Colum- bia or making your way across the prai- Ice road truckers ries of Saskatchewan, slippery roads and reduced visibility can wreak havoc. The Saskatchewan Ministry of High- ways and Infrastructure urge truck Reach us at drivers to conduct thorough trip in- our Western needn’t fret spections, and to give extra time dur- Canada news ing the winter months to complete. bureau “Checking your truck, trailer(s), tires, brakes, lights and other equipment be- Contact How the use of airships would fore you start a trip is always impor- Derek Clouthier tant,” the ministry informed Truck Derek@ West. “With cold weather, extra care should be taken with these regular in- Newcom.ca help the trucking industry spections. -

Cablefax Program Awards 2021 Winners and Nominees

March 31, 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE CFX Program Awards Honoring the 2021 Nominees & Winners PROGRAM AWARDS March 31, 2021 The Cablefax Program Awards has a long tradition of honoring the best programming in a particular content niche, regardless of where the content originated or how consumers watch it. We’ve recognized breakout shows, such as “Schitt’s Creek,” “Mad Men” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” long before those other award programs caught up. In this special issue, we reveal our picks for best programming in 2020 and introduce some special categories related to the pandemic. Read all about it! As an interactive bonus, the photos with red borders have embedded links, so click on the winner photos to sample the program. — Amy Maclean, Editorial Director Best Overall Content by Genre Comedy African American Winner: The Conners — ABC Entertainment Winner: Walk Against Fear: James Meredith — Smithsonian Channel This timely documentary is named after James Meredith’s 1966 Walk Against Fear, in which he set out to show a Black man could walk peace- fully in Mississippi. He was shot on the second day. What really sets this The Conners shines at finding ways to make you laugh through life’s film apart is archival footage coupled with a rare one-on-one interview with struggles, whether it’s financial pressures, parenthood, or, most recently, the Meredith, the first Black man to enroll at the University of Mississippi. pandemic. You could forgive a sitcom for skipping COVID-19 in its storyline, but by tackling it, The Conners shows us once again that life is messy and Nominees sometimes hard, but with love and humor, we persevere. -

On Reality Television During the Great Recession

Societies 2012, 2, 235–251; doi:10.3390/soc2040235 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article Working Stiff(s) on Reality Television during the Great Recession Sean Brayton Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB, T1K 3M4, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2012; in revised form: 22 October 2012 / Accepted: 23 October 2012 / Published: 29 October 2012 Abstract: This essay traces some of the narratives and cultural politics of work on reality television after the economic crash of 2008. Specifically, it discusses the emergence of paid labor shows like Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal and a resurgent interest in working bodies at a time when the working class in the US seems all but consigned to the dustbin of history. As an implicit response to the crisis of masculinity during the Great Recession these programs present an imagined revival of manliness through the valorization of muscle work, which can be read in dialectical ways that pivot around the white male body in peril. In Ax Men, Black Gold and Coal, we find not only the return of labor but, moreover, the re-embodiment of value as loggers, roughnecks and miners risk both life and limb to reach company quotas. Paid labor shows, in other words, present a complicated popular pedagogy of late capitalism and the body, one that relies on anachronistic narratives of white masculinity in the workplace to provide an acute critique of expendability of the body and the hardships of physical labor. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

Thursday Morning, March 10

THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH 10 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest Who Wants to Be The View Actress Michelle Rodri- Live With Regis and Kelly Talent 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (cc) a Millionaire guez. (N) (cc) (TV14) judge Jennifer Lopez. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 Early at 6 (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Aaron Eckhart; Avril Lavigne performs. (N) (cc) The Nate Berkus Show Do-it-your- 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) self projects. (cc) (TVPG) Sit and Be Fit Between the Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Search for the Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) Lions (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Blue Bar Pigeon. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) Better (cc) (TVPG) The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 Portland Public Affairs Paid Paid The Magic School Willa’s Wild Life Through the Bible Zola Levitt Pres- Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Bus (TVY7) ents (TVG) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Unfolding Majesty Life Change Cafe John Bishop TV Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) (cc) World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) George Lopez George Lopez The Young Icons Just Shoot Me My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Maury (cc) (TV14) Swift Justice- Swift Justice- The Steve Wilkos Show Abuse of a 32/KRCW 3 3 (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (TVG) (cc) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) Nancy Grace Nancy Grace young boy. -

Keeping Our Bearings with Difficult People

BEST PRACTICES Betsy Raskin Gullickson, Editor Keeping Our Bearings with The fishermen in Discovery Channel’s The Deadliest Catch Difficult People routinely deal with dangerous conditions caused by the ele- equipment—cages weighing hun- freeze when they come in contact ments. Those of us working in dreds of pounds apiece—during with metal, adding tons of weight offices don’t operate in life- intense work shifts, as much as to the boats and making them top threatening situations, but we 40 hours out of 50. The work heavy and at greater risk of tip- may see some parallels between would be physically demanding ping or sinking, much like the col- the deadly weather and some under the best of conditions, but league who throws cold water on of our difficult colleagues. crab fishing takes place between initiatives. October and January, when arctic A European executive is all-too- weather is extreme. The elements familiar with this kind of difficult hile surfers and swimmers have uncomfortable parallels in person: “We were colleagues at the Ware told to stay home when the work climate. Let’s take a look same hierarchical level; then I got Great White sharks appear close to at some. promoted, and he sort of needed shore, nobody closes the beach Howling Wind. Even when to provoke me to see how I would because of a crab sighting. Yet it’s storms blow winds up to 40 to 50 react. For example, I used to plan Alaskan crabs at the center of the knots, crew members must make the timetables for the week for all Discovery Channel program, The their way across the deck or stand the staff; he would come to me Deadliest Catch. -

Put Your Foot Down

PAGE SIX-B THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 2012 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurniture Your Feed Stop By New & Used Furniture & Appliances Specialists Frederick & May For All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! QUALITY Refrigeration Needs With A •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. Regular •Superior Design and Quality Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FOR ALL Remember We Service 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOUR $ 00 $379 • Animal Health Products What We Sell! •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms • Pet Food & Supplies •Horse Tack FARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty • Farm & Garden Supplies •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty FINANCING AVAILABLE! (Moved To New Location Behind Save•A•Lot) Lumber Co., Inc. Williams Furniture 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. • WEST LIBERTY We Now Have A Good Selection 548 Prestonsburg St. • West Liberty, Ky. 7598 Liberty Road • West Liberty, Ky. TPAGEHE LICKING TWE LVVAELLEY COURIER THURSDAYTHURSDAY, NO, VJEMBERUNE 14, 24, 2012 2011 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Of Used Furniture Phone (606) 743-3405 Phone: (606) 743-2140 Call 743-3136 PAGEor 743-3162 SEVEN-B Holliday’s Stop By Your Feed Frederick & May OutdoorElam’sElam’s Power FurnitureFurniture Equipment SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New4191 & Hwy.Used 1000 Furniture • West & Liberty, Appliances Ky.