World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time-Varying Interdependencies of Tourism and Economic Growth: Evidence from European Countries

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dragouni, Mina; Filis, George; Antonakakis, Nikolaos Working Paper Time-Varying Interdependencies of Tourism and Economic Growth: Evidence from European Countries FIW Working Paper, No. 128 Provided in Cooperation with: FIW - Research Centre International Economics, Vienna Suggested Citation: Dragouni, Mina; Filis, George; Antonakakis, Nikolaos (2013) : Time-Varying Interdependencies of Tourism and Economic Growth: Evidence from European Countries, FIW Working Paper, No. 128, FIW - Research Centre International Economics, Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/121121 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an -

Cornell Dyson Wp0203

WP 2002-03 January 2002 Working Paper Department of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7801 USA Portugal and the Curse of Riches - Macro Distortions and Underdevelopment in Colonial Times Steven Kyle Abstract Portugal and the Curse of Riches - Macro Distortions and Underdevelopment in Colonial Times Steven Kyle Cornell University December 2001 This paper attempts to answer the following question: How, in economic terms, was being colonized by Portugal “different” for Lusophone African countries than was being colonized by France or Britain? Gervase Clarence-Smith addressed this question for the period after 1825, and comes to the conclusion that Portuguese economic motivations were much the same as those for other colonial powers. Nevertheless, this leaves open the question of whether the objective conditions of Portugal’s economy and its development trajectory over the long run (i.e. from the 15th century on) may have affected its colonial relations regardless of whether motivations were the same. The answer to this question is examined in terms of Portugal’s own lack of economic development and the economic processes which led to this. Most important is the fact that Portugal experienced a massive influx of foreign exchange (gold and revenue from the spice trade) during a period when other Northern European countries were undergoing the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution and the consequent transformations in their economies that this engendered. Portugal, however, never underwent these changes until the twentieth century, due at least in part to what is commonly called “Dutch Disease” in the economics literature, a name for a pattern of problems afflicting resource rich countries which distorts their development and retards the growth of productive sectors of the economy. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aiginger, Karl Working Paper Catching-up in Europe: The Experiences of Portugal, Spain and Greece in the Nineties WIFO Working Papers, No. 212 Provided in Cooperation with: Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna Suggested Citation: Aiginger, Karl (2003) : Catching-up in Europe: The Experiences of Portugal, Spain and Greece in the Nineties, WIFO Working Papers, No. 212, Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/128757 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ÖSTERREICHISCHES INSTITUT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG WORKING PAPERS Catching-up in Europe: The Experiences of Portugal, Spain and Greece in the Nineties Karl Aiginger 212/2003 Catching-up in Europe: The Experiences of Portugal, Spain and Greece in the Nineties Karl Aiginger WIFO Working Papers, No. -

Rthe Political Economy of Agricultural Pricing Policy

Public Disclosure Authorized 10198 ThePolitical Economy of Public Disclosure Authorized AgriculturalPricing Policy VO LUME 3 Africa Public Disclosure Authorized and the Mediterranean Edited by AnneO .Krueger i MaunceScbiff i AlbertoVald& Public Disclosure Authorized A World Bank Comparative Study ?' -i I rThe PoliticalEconomy of Agricultural PricingPolicy VOLUME3 AFRICA ANDTHEM MEDITERRANEAN A World Bank Comparative Study Thne PoliticalEconomy o Agricultural PricingPolicy VOLUME 3 AFRICA ANDlTHE MEDITERRANEAN A World Bank Comparative Study Edited by * Anne 0. Krueger * Maurice Schifff * Alberto Valde' PUBLISHED FOR THE WORLD BANK The Johns Hopkins UniversityPress Baltimore and London (D 1991The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore, Maryland 21211-2190,U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing October 1991 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and policies of the World Bank or its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce portions of it should be sent to Director, Publications Department, at the address shown in the copyright notice above. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally give permission promptly and, when the reproduction is for noncommercial purposes, without asking a fee. Permissions to photocopy portions for classroom use is not required, though notification of such use having been made will be appreciated. The complete backlist of publications from the World Bank is shown in the annual Index of Publications, which contains an alphabetical title list and indexes of subjects, authors, and countries and regions. -

Recovery Program

an ' Recovery Program PORTUGAL ~ . COUNTRY STUDY Economic Cooperation Administration February 1949 • Washington, D. C. European Recovery Program Economic Cooperation Administration Febrary 1949 e Washington, D. C. United States Government Printing Office, Washington :1949 This document is based on the best information regarding Portugal currently available to the Economic Cooperation Administration, and the views expressed herein are the considered judgment of the Admin istration. Both the text and the figures for 1949-50 are still prelimi nary in character; participating countries will therefore understand that this report cannot be used to support any request, either to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation or to the,Eonomic Cooperation Administration, for aid in any particular amount for any. country or for any particular purchase or payment. FBMRNTAY 14, 1949. Administrator. III Contents Page -" 1 PART I. SUAIU AR Y AND CONCLUSIONS -- ......................... PART II: CHAPTER I. THE CURRENT SITUATION OF THE PORTuGUES ECONOMY: A. General Characteristics of the Portuguese Economy ------ ------ - B. Production --------------------------------------------- 4 C. Internal Finance---------------------------- -------------- 6 D. External Accounts: 1. General Charatetistics -------- "--------------------------7 2. Balance of Payments..--------------------------------- 10 3. Gold and Foreign Exchange Btoldings--------- ------------- 12 CRAPTER II. JUSTIFICATION OF POSSIBLE ERP AID IN 1949-50: A. Introduction ---------------------------------------------- -

The Economy of Portugal and the European Union: from High Growth Prospects to the Debt Crisis

The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 53 (2013) 345–352 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/qref The economy of Portugal and the European Union: From high growth prospects to the debt crisis a,∗ a,b a Werner Baer , Daniel A. Dias , Joao B. Duarte a University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States b CEMAPRE, Portugal a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper documents some of the recent economic history of Portugal, since its accession to the EEC, to Received 12 April 2012 the adoption of the Euro and more recently to the financial and economic crisis. In the first part of the Accepted 14 June 2012 paper we show the economic performance of Portugal during the last 25 years till now, from the fast Available online 6 August 2012 growth of the late 1980s and early 1990s to the current recession. We point out some of the reasons for this trajectory – slow productivity growth, disconnection between productivity and wages, continued Keywords: external and public deficits – and choose three areas that must be improved in order to reverse the current Portugal downward spiral – justice needs to be more effective and faster, education needs to improve its quality European Union and distribution across the population, and the public administration must become more efficient. Core and periphery © 2012 The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Published by Elsevier B.V. -

Decomposing the Growth of Portugal: a C Ase for Increasing Demand, Not Austerity, in a Small European Economy

DECOMPOSING THE GROWTH OF PORTUGAL: A CASE FOR INCREASING DEMAND, NOT AUSTERITY, IN A SMALL EUROPEAN ECONOMY Carlos Pinkusfeld Bastos1 & Gabriel Martins da Silva Porto2 ABSTRACT This paper presents an analysis of Portugal's economy from 1999 to 2015, providing an alternative to explanations that present the situation faced by Southern European countries after the Great Recession as a matter of excessive expenditure or loss in competitiveness. Based upon the Sraffian Supermultiplier model, we look at how demand components evolved along the analyzed period, in a growth accounting setting. This assessment evidences that insufficient effective (public) demand -- not balance-of-payments constrains nor an alleged excess of public expenditure -- is what explains Portugal's low-to-negative growth rates from 2001 forward. Given the limited productive structure, a labor market that is not strong enough to guarantee a solid internal credit expansion and the present institutional setting (which makes fiscal expenditure an also limited source of effective demand), we conclude that the only way for Portugal to abandon the low growth path would be a more cooperative fiscal stance from the European Union. KEYWORDS: Sraffian Supermultiplier, Growth Accounting, Euro Crisis, Portugal JEL CLASSIFICATION: E42, E58, E62 2016 1 Professor: Institute of Economics, Rio de Janeiro Federal University (UFRJ). 2 Researcher: Political Economy Group – Institute of Economics, Rio de Janeiro Federal University (UFRJ). 1. Intro Eight years after the start of the 2008 crisis Portugal did not recover the level of GDP per capita it had prior to this crisis. The labor market still shows a larger number of unemployed workers, a higher rate of unemployment and lower wages compared to the pre crisis period. -

Portuguese Guinea and the Liberation Movement•

Report <Yn PORTUGUESE GUINEA AND THE LIBERATION MOVEMENT• The following is Hr. Cabral's statement to the U.S. /louse Com mittee on Foreign AffDlrs on February 26, 1970. HR. CADRAL: Sir, I have some notes. HR. CIIARLE:S C. DIGGS, JR., Chalrman of the Subcommittee on Africa: You may proceed, air. HR. CJIDRAL: Sir, I thank you very much. I would liko to say first that my colonial language is Portuguese, and I would like to apeak Portuguese, but in order to get more understanding, I will try to speak English. First, I would like, on beha~f of the people of Guinea and cape Verde, on behalf of all my fellows, to salute you and the COtlfti ttee and to thank you very much for this opport\Ulity to inform you about the situation in our country, the situation of our people. We have been for seven years fighting a very hard fig~t against colonial dominati on for freedom, independence and progress. Our presence here is, first of all, to salute you and the lln1orlcan people. We think the major part of the 1\mcdcan nati on is with us in t hiu hard fight again at col onial rule. lln<l 1 t is very good for us to tell you that we are fighting, and are fol lowing the example given by the l'.merican people when they launch ed a great struqgle for the independence of this country. We would like alao to thnnk you very much, and this com mittee, for the work done in Africa about the African problems, for your last visit in Africa in a special study mission , and to tell you that maybe it was enough to show our agre et~~ent with the conclusions of your report, but it is necessary to inform you and to help you in order that you may help us. -

Portuguese Labour Market Governance in Comparative Perspective

Draft chapter for the Oxford Handbook of Portuguese Politics, ed. J. Fernandes, P. Magalhaes and A. Costa Pinto. Portuguese Labour Market Governance in Comparative Perspective Alexandre Afonso, Leiden University Abstract. This chapter analyses the core characteristics of labour market governance in Portugal in a comparative perspective, analyzing the interplay of public and private regulation in the setting of wages and employment conditions. The chapter describes the main characteristics of the Portuguese employment model within the European context and how it departs from other Southern European countries, notably when it comes to female and low-skilled employment. The chapter argues that the power relationships that emerged out of the transition to democracy favoured a more liberal employment regime than in Spain, resulting in a lower threshold of unemployment but also higher income inequalities and lower wage protections. The models have tended to converge in recent years, and income inequality in Portugal has diminished. The chapter highlights the high level of female employment since the 1960s, a characteristic that departs significantly from other Southern European countries. It is explained by specific contextual factors, notably the legacy of the colonial war and high rates of emigration. Keywords: Portugal, labour market policies, collective bargaining, employment protection, employment, gender Words: 6557 Introduction Portugal is often bundled within the broader “Southern” or “Mediterranean” model of welfare and employment when it comes to the governance of its labour market (Ferrera 1996; Zartaloudis and Kornelakis 2017). In many ways, Portuguese labour market governance indeed shares many characteristics with Spain, Italy or Greece: high levels of segmentation between “insiders” and “outsiders”, relatively high levels of inequality, the large size of the informal sector, and a reliance on the state to regulate wages and employment rather than on social partners alone, as in Scandinavia. -

Economic Recovery in the Euro Area: the Asymmetrical Recoveries of Greece, Ireland and Portugal Following the Late 2000S European Debt Crisis

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 4-2020 Economic Recovery in the Euro Area: The Asymmetrical Recoveries of Greece, Ireland and Portugal Following the Late 2000s European Debt Crisis Zachary A. Jacobs University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Comparative Politics Commons Recommended Citation Jacobs, Zachary A., "Economic Recovery in the Euro Area: The Asymmetrical Recoveries of Greece, Ireland and Portugal Following the Late 2000s European Debt Crisis" 01 April 2020. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/248. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/248 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Economic Recovery in the Euro Area: The Asymmetrical Recoveries of Greece, Ireland and Portugal Following the Late 2000s European Debt Crisis Abstract The late 2000s financial crisis within the euro area had distinct effects on different member states of the polity despite a shared monetary policy and supranational organizational structure. Certain countries like Greece suffered a prolonged (and ongoing) economic crisis while others, Portugal and Ireland as discussed in this thesis, had periods of crisis but returned to normalcy after some time. Commitment to certain policies at the national level cannot fully explain the speed of these recoveries; Portugal and Ireland, for instance, had different levels of commitment to and popular willingness to endure austerity measures. All three countries will be discussed considering their parliamentary structures (i.e. whether governments held a parliamentary majority, were maintained by an ideologically consistent coalition, etc.) to show that the power and decisiveness of ruling parties played some role in economic recovery. -

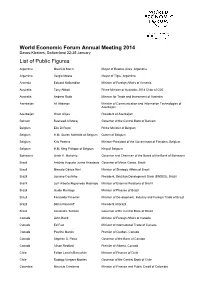

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

The Gross Agricultural Output of Portugal: a Quantitative, Unified Perspective, 1500-1850

European Historical Economics Society EHES WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY | NO. 98 The Gross Agricultural Output of Portugal: A Quantitative, Unified Perspective, 1500-1850 Jaime Reis Universidade de Lisboa JULY 2016 EHES Working Paper | No. 98 | July 2016 The Gross Agricultural Output of Portugal: A Quantitative, Unified Perspective, 1500-1850 Jaime Reis* Universidade de Lisboa Abstract This paper presents the first estimate to date of the anual output of Portugal’s agriculture between 1500 and 1850. It adopts the well-known indirect approach, which uses a consumption function for agricultural products. Prices and wages for this come from a recently created data base. It also verifies the assumption that agricultural consumption is equal or very close to national output. The method for calculating the income variable in the function is innovative since labour supplied per worker is not constant over time as in many estimates. Instead, it is made to vary, reflecting the ‘industrious revolution’ which occurred in Portugal during much of the period considered. The main finding is that the country’s agriculture displays a long-run upward trend, contrary to traditional stagnationist views. It was unable, however, to keep up with the even stronger concomitant growth of population. Food consumption consequently declined, sharply in the 16c. but more slowly in the 17c. It recovered during part of the 18c. but after the 1750s it slipped again and down to 1850 it lost all these welfare gains. JEL classification: N53, O13, Q10 Keywords: agricultural output, early modern Portugal, cycles, food consumption * This study has received valuable financial support from the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (projects PTDC/HAH/70938/2006 and PTDC/HIS-HIS/123046/2010).