Lucky Man Struggling Haberdashery That Features in “Cousins” (1983) and “The Death of Horton Foote’S Three Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

Board of Directors. I Want to Make Sure That There’S a Diversity Ourselves — We Live with Them for Long Periods of of Voices Being Published by DPS

ISSUE 16 DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE SPRING 2015 ROUND TABLE with JOHN PATRICK SHANLEY, Dramatists Play Service POLLY PEN, and LYNN NOTTAGE is very fortunate not just to publish and license the best BY PETER HAGAN, PRESIDENT American playwrights, but also to have four of them sit on our the publishing conversation. As a woman of always going to be slightly different from that of the color, I also see my role as one of advocacy; agents. Our plays are creative extensions of Board of Directors. I want to make sure that there’s a diversity ourselves — we live with them for long periods of of voices being published by DPS. time; we keep them close and protected until we release them into the world. The founding charter of the Play Service, back in As time has gone by, have you seen your Then we entrust our plays 1936, called for the Board to be split evenly position as a playwright member change? to others for safekeeping: between playwrights (all members of the initially agents, and eventually Dramatists Guild) and agents. Back then, the star John Patrick Shanley: When I first served on publishing companies like playwrights included Howard Lindsay, George the Board, I was skeptical and challenging DPS. For better or worse, Abbott, and Sidney Howard. Today our stars are and, frankly, young. But over time I morphed agents can approach the Donald Margulies, Polly Pen, Lynn Nottage, and from opponent to colleague. business of publishing with John Patrick Shanley, who have been members a certain level of objectivity of the board ranging from five years (Nottage) to PP: Ways of thinking about how theatrical and distance; however, it’s over 20 (Shanley). -

Theatrical CV

Represented by Miles Polaski SOUND DESIGNER & COMPOSER Michael Griffo [email protected] 773.905.4529 [email protected] www.milespolaski.com 212-556-6714 SOUND DESIGN — PLAYS (selected credits) PRODUCTION PLAYWRIGHT PRODUCING COMPANY DIRECTOR WHERE STORMS ARE BORN Harrison David Rivers Williamstown T h eatre Festival Saheem Ali TWO CLASS ACTS A.R. Gurney The Flea Theatre Stafford Arima FULFILLMENT Thomas Bradshaw The Flea Theatre Ethan McSweeny BOOK OF JOSEPH Karen Hartman Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Barbara Gaines BYHALIA MISSISSIPPI Evan Linder Contemporary American Thtr. Fest. Marc Masterson WASHER DRYER Nandita Shenoy Ma-Yi Theatre Benjamin Kamine SAGITTARIUS PONDEROSA MJ Kaufman Nat. Asian American Theatre Co. Ken Rus Schmoll A CHRISTMAS CAROL add. James Palmer Trinity Repertory James D. Palmer THE HAIRY APE Eugene O’Neill Goodman / The Hypocrites Sean Graney MEN ON BOATS Jaclyn Backhaus American Theatre Company William Davis PICNIC and ...LITTLE SHEBA William Inge Transport Group Jack Cummings III WANT Zayd Dohrn Steppenwolf Theatre Kimberly Senior MAN IN LOVE Christina Anderson Steppenwolf Theatre Robert O’Hara THE KID THING Sarah Gubbins Chicago Dramatists -

Selected Correspondence from the Horton Foote

SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 by SUSAN CHRISTENSEN Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Horton Foote for his generosity in granting me permission to include transcriptions of his family members’ correspondence in my dissertation. I would also like to thank his daughter Hallie for her kind assistance. I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Laurin Porter, my supervising professor, an extraordinary teacher, a remarkable scholar, and a generous and thoughtful person. During my graduate studies, her wisdom has inspired me and her encouragement has sustained me. I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to the members of my graduate committee, Dr. Desirée Henderson and Dr. Neill Matheson, and also to Dr. Wendy Faris and Dr. Thomas Porter, for their kindness and their work on my behalf. I am grateful to Dr. Russell Martin III, the director of the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University, and his staff, who assisted me during the many months I spent conducting archival research. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my husband Robert for his unwavering support and love. July 16, 2008 ii ABSTRACT SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 Susan Christensen, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Laurin Porter This dissertation includes a discussion of archival research and editorial procedures employed in the study, introductory essays on the private correspondence of the family of Horton Foote, and transcriptions of one hundred letters selected from the personal correspondence in the Horton Foote Collection reposited in the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, with extensive annotations and ancillary materials. -

Curriculum Vitae: Bruce F. Kawin

October 30, 2020 Curriculum Vitae: Bruce F. Kawin Professor Emeritus of English University of Colorado at Boulder Boulder, CO 80309 Home: 4393 13th St. Boulder, CO 80304 Phone: (303) 449-4845 (land line) — (303) 514-6707 (cell; use this or e-mail until further notice) Fax: (303) 449-2503 E-mail: [email protected] Born: Los Angeles, CA Education: Ph.D.: Cornell University, September 1970 Major: 20th Century British and American Literature Minor: Film History and Aesthetics Thesis: Telling It Again and Again: The Aesthetics of Repetition M.F.A.: Cornell University, June 1969 Major: Creative Writing Minor: Filmmaking Thesis: Slides Summer program in Documentary Film Production, UCLA, August 1968 B.A. cum laude: Columbia College, Columbia University, June 1967 Major: English and Comparative Literature Teaching Experience: Professor of English: English Department, University of Colorado at Boulder, 1975-2015. (Professor Emeritus, 2015-present; Full Professor since 1980; tenure awarded, 1979; Associate Professor, 1977- 80; Assistant Professor, 1975-77.) Taught half-time in Film Studies Program 1975-2006 (two Film Studies courses/year), then one Film Studies course/year through 2014; other film courses after 2006 taught in English Dept. Fields: Modern Literature, Film History and Theory, Creative Writing. Visiting Fellow: Theater Arts Board, College 5, University of California at Santa Cruz, 1980-81. Fields: Film History and Theory. Specialist in Film Analysis: Center for Advanced Film Studies, American Film Institute, 1974. Lecturer in English and Film: English Department, University of California at Riverside, 1973-75. Fields: Modern Literature, Film History, Composition, Women Studies. Assistant Professor of English: English Department, Wells College, 1970-73. -

Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde Edited by LESTER D. FRIEDMAN Syracuse University PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain ᭧ Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Stone Serif 10/14 pt. System DeskTopPro/UX [BV] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde / edited by Lester D. Friedman. p. cm. – (Cambridge film handbooks series) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-521-59295-X – ISBN 0-521-59697-1 (pbk.) 1. Bonnie and Clyde (Motion picture) I. Friedman, Lester D. II. Series. PN1997.B6797 1999 791.43'72 – dc21 98-32173 CIP ISBN 0 521 59295 X hardback ISBN 0 521 59697 1 paperback LESTER D. FRIEDMAN Introduction ARTHUR PENN’S ENDURING GANGSTERS HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES: COUNTERCULTURAL CINEMA Boy meets girl in small-town Texas. Their crime spree begins as girl goads boy into robbing a grocery store; they speed out of town in a stolen car, spirits high. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

20 Films on Politics and the Media | Thecommentary.Ca Page 1 of 5

20 films on politics and the media | thecommentary.ca Page 1 of 5 thecommentary.ca » • Home • About • Biography • Links Search... Home » The Commentary 20 films on politics and the media 29 December 2009 | Email This Post | Print This Post BY JOSEPH PLANTA VANCOUVER – A few weeks ago, Sean Holman, the talented and prodigious editor of Public Eye Online was on the program to discuss the year that was and the year to come in provincial politics. We got to talking movies, when I’d asked him if he’d seen State of Play, the fine American film based on the British miniseries of the same name. He suggested two other films: The Candidate and Shattered Glass. This got me thinking about what films had the best depictions of politics, media, journalism and the writing process. I came up with a few, and limited myself to twenty which seemed a workable number. Twenty favourites, as it were. Of course the list is subjective, and is in no particular order. I suspect if I ever get to watching Dr. Strangelove, or The Front Page, or Bob Roberts, or Silver City, they might be added to the list, perhaps even bumping off something already here. There’s nothing on this list that was made for television, otherwise the House of Cards trilogy would be here, as well as the original British miniseries State of Play, The Thick of It, The West Wing, and of course, the Yes, Minister/Yes, Prime Minister tandem. Perhaps Mr. Holman or others would like to add to or debate my choices. -

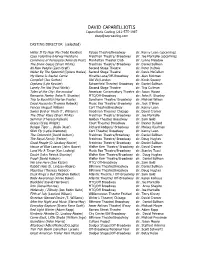

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. -

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony: St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard Bernstein BY KENNETH H. WINN 34 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2018/2019 In May 1944 25-year-old publicized story from a New Leonard Bernstein, riding a York high school newspaper, had tidal wave of national publicity, bobbysoxers sighing over him as was invited to serve as a guest the “pin-up boy of the symphony.” conductor of the St. Louis They, however, advised him to get The Pin-Up Boy 3 Symphony Orchestra for its a crew cut. 1944–1945 season. The orchestra For some of Bernstein’s of the Symphony and Bernstein later revealed that elders, it was too much, too they had also struck a deal with fast. Many music critics were St. Louis and the RCA’s Victor Records to make his skeptical, put off by the torrent first classical record, a symphony of praise. “Glamourpuss,” they Rise of Leonard Bernstein of his own composition, entitled called him, the “Wunderkind Jeremiah. Little more than a year of the Western World.”4 They BY KENNETH H. WINN earlier, the New York Philharmonic suspected Bernstein’s performance music director Artur Rodziński Jeremiah was the first of Leonard Bernstein’s was simply a flash-in-the-pan. had hired Bernstein on his 24th symphonies recorded by the St. Louis Symphony The young conductor was riding birthday as an assistant conductor, Orchestra in the spring of 1944. (Image: Washing- a wave of luck rather than a wave a position of honor, but one known ton University Libraries, Gaylord Music Library) of talent.