Part 0-Prelims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Faith in the Charity and Development Sector in Karachi and Sindh, Pakistan

Religions and Development Research Programme The Role of Faith in the Charity and Development Sector in Karachi and Sindh, Pakistan Nida Kirmani Research Fellow, Religions and Development Research Programme, International Development Department, University of Birmingham Sarah Zaidi Independent researcher Working Paper 50- 2010 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: z How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? z How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? z In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. -

Research Publications by DISTINCTIONS Any Scientist of Pakistan in Last 10 Year and SERVICES Secretary General, the Chemical Society of Pakistan

CV and List of Publications PROF. DR. MUHAMMAD IQBAL CHOUDHARY (Hilal-e-Imtiaz, Sitara-e-Imtiaz, Tamgha-ei-Imtiaz) International Center for Chemical and Biological Sciences (H. E. J. Research Institute of Chemistry, Dr. Panjwani Center for Molecular Medicine and Drug Research) University of Karachi, Karachi-75270 Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 34824924, 34824925 Fax: 34819018, 34819019 E-mail: [email protected] Web Page: www.iccs.edu Biodata and List of Publications Pag No. 2 MUHAMMAD IQBAL CHOUDHARY (Hilal-e-Imtiaz, Sitara-e-Imtiaz, Tamgha-e-Imtiaz) D-131, Phase II, D. O. H. S., Malir Cant., Karachi-75270, Pakistan Ph.: 92-21-4901110 MAILING INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES ADDRESS (H. E. J. Research Institute of Chemistry Dr. Panjwani Center for Molecular Medicine and Drug Research) University of Karachi Karachi-74270, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 34824924-5 Fax: (92-21) 34819018-9 Email: [email protected] Web: www.iccs.edu DATE OF BIRTH September 11, 1959 (Karachi, Pakistan) EDUCATION Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) (University of Karachi ) 2005 Ph.D. (Organic Chemistry) 1987 H. E. J. Research Institute of Chemistry University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan Thesis Title: "The Isolation and Structural Studies on Some Medicinal Plants of Pakistan, Buxus papillosa, Catharanthus roseus, and Cissampelos pareira." M.Sc. (Organic Chemistry) 1983 University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan B.Sc. (Chemistry, Biochemistry, Botany) 1980 University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan AWARDS & Declared as the top most scientist (Number 1) among 1,650 HONORS scientists of Pakistan in all disciplines / fields of science and technology (year 2012) by the Pakistan Council for Science and Technology (Ministry of Science and Technology), Pakistan. -

Governance Structure of the State Bank of Pakistan

Governance Structure of the State Bank of Pakistan The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) is incorporated under the State Bank of Pakistan Act, 1956, which gives the Bank the authority to function as the central bank of the country. The Act mandates the Bank to regulate the monetary and credit system of Pakistan and to foster its growth in the best national interest with a view to securing monetary stability and fuller utilization of the country’s productive resources. Central Board of Directors The State Bank of Pakistan is governed by an independent Board of Directors, which is responsible for the general superintendence and direction of the affairs of the Bank. The Board is chaired by the Governor SBP and comprises of 8 non-executive Directors and Secretary Finance to the Federal Government. The Governor SBP is also the Chief Executive Officer of the Bank and manages the affairs of the Bank on behalf of the Central Board. The SBP Act, 1956 (as amended) stipulates that the Board members should be eminent professionals from the fields of economics, finance, banking and accountancy and shall have no conflict of interest with the business of the Bank. During FY13, all 7 vacant positions on the Board were filled through appointment of Directors by the Federal Government. Out of these 7 newly appointed Directors, 5 were appointed on February 26, 2013 followed by 2 appointments in March, 2013. Brief profile of the members of the Board is given on pages 9-10. The current composition of the Board brings a diverse range of professional expertise, adding value to the deliberations. -

Aurat Foundation

ResearchedMaliha Zia and Written By Pakistan NGO Alternative Report Riffat Butt onExecutive CEDAW Summary– 2005-2009 (With Updated Notes - 2009-2012) Articles 1 – 4: ReviewedNeelam Hussain By Naeem Mirza Definition of Discrimination; Policy Measures Nasreen Azhar to be undertaken to Eliminate Discrimination; Guarantee of Younas Khalid Basic Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms on an Equal ArticleBasis with 5: Men; Temporary Special Measures to Achieve ArticleEquality 6: Article 7: Sex Roles and Stereotyping Article 8: Trafficking and Prostitution Data Input by Aurat Article 9: Political and Public Life Foundation’s Team Participation at the International Level Article 10: Mahnaz Rahman, Rubina Brohi Nationality Article 11: (Karachi), Nasreen Zehra, Article 12: Equal Rights in Education Ume-Laila, Mumtaz Mughal, Article 13: Employment (Lahore), Shabina Ayaz, Article 14: Healthcare and Family Planning Saima Munir (Peshawar), Economic, Social & Cultural Benefits Haroon Dawood, Saima Javed Article 15: (Quetta), Wasim Wagha, Rural Women Article 16: Rabeea Hadi, Shamaila Tanvir, General RecommendationEquality before the 19: Law Farkhanda Aurangzeb, Myra Marriage and Family Imran (Islamabad) Violence against Women ChaptersImplementing Contributed CEDAW By in Pakistan DemocracyBy Tahira Abdullah and Women’s Rights: Pakistan’s Progress (2007-2012) Decentralization,By Ayesha Khan 18th Constitutional Amendment and Women’s Rights MinorityBy Rubina WomenSaigol of Pakistan: A Case of Double Jeopardy By Peter Jacob and Jennifer Jag Jewan Prepared By ii ThisAll publication rights is provided reserved gratis or sold, subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. -

Framework for Economic Growth, Pakistan

My message to you all is of hope, courage and confidence. Let us mobilise all our resources in a systematic and organised way and tackle the grave issues that confront us with grim determination and discipline worthy of a great nation. – Muhammad Ali Jinnah Core Team on Growth Strategy This framework for economic growth has been prepared with the help of thousands of people from all walks of life who were part of the many consultative workshops on growth strategy held inside and outside Pakistan. The core team was led by Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque, Minister/Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission, and included: • Dr. Khalid Ikram, Former Advisor, World Bank • Mr. Shahid Sattar, Member, Planning Commission • Dr. Vaqar Ahmed, National Institutional Adviser, Planning Commission • Dr. Talib Lashari, Advisor (Health), Planning Commission • Mr. Imran Ghaznavi, Advisor, P & D Division • Mr. Irfan Qureshi, Chief, P & D Division • Mr. Yasin Janjua, NPM, CPRSPD, Planning Commission • Mr. Agha Yasir, In-Charge, Editorial Services, CPRSPD • Mr. Nohman Ishtiaq, Advisor, MTBF, Finance Division • Mr. Ahmed Jamal Pirzada, Economic Consultant, P & D Division • Mr. Umair Ahmed, Economic Consultant, P & D Division • Ms. Sana Shahid Ahmed, Economic Consultant, P & D Division • Ms. Amna Khalid, National Institutional Officer, P & D Division • Mr. Muhammad Shafqat, Policy Consultant, P & D Division • Mr. Hamid Mahmood, Economist, P & D Division • Mr. Muhammad Abdul Wahab, Economist, P & D Division • Mr. Hashim Ali, Economic Consultant, P & D Division • Sara Qutab, Competitiveness Support Fund • Ms. Nyda Mukhtar, Economic Consultant, P & D Division • Mr. Mustafa Omar Asghar Khan, Policy Consultant, P & D Division • Dr. Haroon Sarwar, Assistant Chief, P & D Division • Mr. -

Acid Violence in Pakistan

Taiba Zia Acid Violence in Pakistan 47% of Pakistan’s nearly 190 million population are women.1 The country ratified CEDAW in 1996.2 More than 15 years have passed since then but Pakistan still has a dismal women’s rights record, ranking 134 out of 135 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report of 20123. By far the most egregious of these are crimes of violence against women, which range from “honor” killings4 and rapes to domestic violence and acid crimes. The Aurat Foundation, a local women’s rights organization, reports 8539 cases of violence against women in 2011, an alarming increase of 6.49% from the previous year. Of these, sexual assault increased by 48.65%, acid throwing by 37.5%, “honor” killings by 26.57% and domestic violence by 25.51%. The organization noted 44 cases of acid violence in 2011 compared to 32 in 2010. An important point to remember here is that these are only the cases reported in the media.5 Indeed, it is widely acknowledged that most cases do not make it to the media as women tend not to come forth with the crimes for a number of reasons, such as fear, stigma, lack of rights awareness, economic dependence on the perpetrators, lack of family and societal support, and mistrust of the police and judiciary, to name a few. Collecting data from isolated rural areas is also difficult. Valerie Khan, Chair of Acid Trust Foundation Pakistan, estimates acid attacks in Pakistan number 150 each year while Shahnaz Bokhari, chief coordinator at the Progressive Women’s Association, states that her organization has documented over 8800 cases of victims burnt by acid and fire since 1994.6 Bokhari adds the caveat that her figures are only from “Rawalpindi, Islamabad, and a 200-mile radius” and not the entire country. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

PROF. DR. ATTA-UR-RAHMAN, FRS Nishan-E-Imtiaz, Hilal-I-Lmtiaz, Sitara-I-Lmtiaz, Tamgha-I-Lmtiaz

List of Publications Atta-ur-Rahman Page 1 PROF. DR. ATTA-UR-RAHMAN, FRS Nishan-e-Imtiaz, Hilal-i-lmtiaz, Sitara-i-lmtiaz, Tamgha-i-lmtiaz PRESIDENT Network of Academies of Science in Countries of the Organization of Islamic Conference (NASIC) and Patron-in-Chief InternationalCenter for Chemical and Biological Sciences (H.E.J. Research Institute of Chemistry and Dr. PanjwaniCenter for Molecular Medicine and Drug Research) University of Karachi, Karachi Prof. Atta-ur-Rahman has over 1002 publications in the fields of organic chemistry including 37 patents, 173 books and 68 chapters in books published by major U.S. and European presses and 724 research publications in leading internatinal journals. BOOKS NAME OF BOOKS COUNTRY 1. “Biosynthesis of Indole Alkaloids”, Atta-ur-Rahman and A. Basha, Clarendon Press, UK Oxford(1983). 2. “Pakistan EncyclopaediaPlanta Medica,” Vol. I, Atta-ur-Rahman, H.M. Said and V.U. Pakistan Ahmad, Hamdard Foundation Press, Karachi (1986). 3. “Natural Product Chemistry”, Atta-ur-Rahman, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg (1986). Germany 4. “New Trends in Natural Products Chemistry”, Atta-ur-Rahman and P.W. Le Quesne, The Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam (1986). Netherlands 5. “Pakistan EncyclopaediaPlanta Medica”, Vol. 2, H.M. Said, V.U. Ahmad and Atta-ur- Pakistan Rahman, Hamdard Foundation Press, Karachi (1986). 6. “Nuclear Magnetic Resonance”, Atta-ur-Rahman, Springer-Verlag, New York(1986). USA Japanese Translation by Prof. Motoo Tori and Prof. Hiroshi Hirota published by Springer- Verlag, Tokyo (1988)]. 7. “Recent Advances in Natural Product Chemistry”, Atta-ur-Rahman, Shamim Printing Pakistan Press, Karachi (1987). Page 1 of 69 List of Publications Atta-ur-Rahman Page 2 8. -

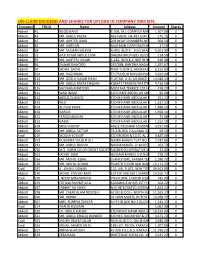

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

The Case of the Omar Asghar Khan

From Analysis to Impact Partnership Initiative Case Study Series The international community responded to the massive earthquake that struck Northwest Pakistan in 2005 with a flood of aid to help rebuild the devastated region. Unfortunately, three years after the quake little progress had been made to restore housing and critical public infrastructure. The Omar Asghar Khan Development Foundation mobilized the people in the Northwest to hold the government to account. Photo courtesy of the Omar Asghar Khan Development Foundation. The following presents a case study of the impact that civil society budget analysis and advocacy can have on government budget policies, processes, and outcomes, particularly as these relate to efforts to eliminate poverty and improve governance. This is a summary of a more in-depth study prepared by Dr. Pervez Tahir as part of the Learning Program of the IBP’s Partnership Initiative. The PI Learning Program seeks to assess and document the impact of civil society engagement in public budgeting. EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION IN outcome was a rapid increase in the rate of construction in the housing, health, water supply, and sanitation sectors. PAKISTAN: THE CASE OF THE OMAR ASGHAR KHAN DEVELOPMENT THE ISSUES: HOUSING AND FOUNDATION’S CAMPAIGN INFRASTRUCTURE AFTER THE On 8 October 2005 a devastating earthquake shook the EARTHQUAKE Hazara region and the Azad Kashmir province in Northwest Managing a disaster of the scale of the 2005 earthquake was Pakistan, destroying huge numbers of shelters, livelihoods, and beyond the capacity of Pakistan, a resource-starved and badly lives in an already marginalized region of this poor country. -

Islamabad Peace Exchange – Organisations Attending

ISLAMABAD PEACE EXCHANGE – ORGANISATIONS ATTENDING The Islamabad Peace Exchange aims to bring together a diverse group of civil society organisations from across Pakistan, all of whom share a strong commitment to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. We hope that each participant will bring different experiences and contexts to share, as well as common lessons from their day to day operations. The event will be jointly hosted by the British Council in Pakistan, and the British charity, Peace Direct. Below is a list of the organisations who will be attending. For more information contact John Bainbridge: [email protected] Organisation: Association for Behaviour and Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) Representative: Ms. Shad Begum, Executive Director Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] ; [email protected] The Association for Behaviour & Knowledge Transformation (ABKT) is an organisation of leading social entrepreneurs from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Founded in 1994, it is a nationally recognised NGO that strives to improve the lives of underdeveloped and vulnerable communities, with a special focus on women, youth and children in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. ABKT is currently mobilising and linking young people from across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to ensure their effective and constructive contribution to peace in the region. ABKT has organised many peacebuilding events, such as the Peace and Development Seminar in October 2010, and the District Level Forum on Peace in 2010. Organisation: Aware Girls Representative: Ms. Gulalai Ismail, Chairperson Location: Peshawar Contact details: [email protected] Aware Girls seeks to enable young people from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province and Tribal Area of Pakistan to develop the leadership and peer-education skills necessary for promoting peace and non-violence in the region. -

Physician Assistant's Program

SIUTnews Events SIUT APRIL 2014 Physician Assistants Program Gone too early, what a loss! Prof. Javed Iqbal Kazi The pathology community in general and the nephropathology Opening New and renal transplant pathology community in particular have Doors in Technical suffered a great loss by the sudden and tragic death of Education -All Free Professor Javed Iqbal Kazi. Dr. Kazi started his long with Dignity association with SIUT in 1995 as Consultant Histopathologist Physician Assistants at work which continued till his last breath. He was the main driving It is universally recognized that education compromised at the Z.A. School or the force for the development of is a fundamental right of every citizen. That School of Nursing. Following the SIUT Histopathology Department of includes accessibility to technical and philosophy that the medical care it provides SIUT to its present status of a professional training. Unfortunately, is world class, state-of-the-art, the training state of the art diagnostic and Pakistan does not provide this right to every at SIMS is also of the highest quality. research facility. youth because it carries a heavy price. Besides, SIMS was created within the SIUT held a condolence meeting Most aspiring and talented young women framework of the SIUTs expansion strategy where Professor Rizvi said, "In and men cannot even imagine themselves of following a need-driven approach. his death, we have not killed a paying the high fees demanded of them The School of Nursing began in 2006 with single person, but rather have from institutions that have commercialized the initiation of a one-year certified Nursing buried an era of technological education.