Brooding Behaviour and Nestling Growth of the Lyre-Tailed Nightjar Uropsalis Lyra Harold F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% Chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% Chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% Chance

Colombia: Chocó Prospective Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% chance A B C Tawny-breasted Tinamou 2 Nothocercus julius Highland Tinamou 3 Nothocercus bonapartei Great Tinamou 2 Tinamus major Berlepsch's Tinamou 3 Crypturellus berlepschi Little Tinamou 1 Crypturellus soui Choco Tinamou 3 Crypturellus kerriae Horned Screamer 2 Anhima cornuta Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna autumnalis Fulvous Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna bicolor Comb Duck 3 Sarkidiornis melanotos Muscovy Duck 3 Cairina moschata Torrent Duck 3 Merganetta armata Blue-winged Teal 3 Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal 2 Spatula cyanoptera Masked Duck 3 Nomonyx dominicus Gray-headed Chachalaca 1 Ortalis cinereiceps Colombian Chachalaca 1 Ortalis columbiana Baudo Guan 2 Penelope ortoni Crested Guan 3 Penelope purpurascens Cauca Guan 2 Penelope perspicax Wattled Guan 2 Aburria aburri Sickle-winged Guan 1 Chamaepetes goudotii Great Curassow 3 Crax rubra Tawny-faced Quail 3 Rhynchortyx cinctus Crested Bobwhite 2 Colinus cristatus Rufous-fronted Wood-Quail 2 Odontophorus erythrops Chestnut Wood-Quail 1 Odontophorus hyperythrus Least Grebe 2 Tachybaptus dominicus Pied-billed Grebe 1 Podilymbus podiceps Magnificent Frigatebird 1 Fregata magnificens Brown Booby 2 Sula leucogaster ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 ● Fax (520) -

A Woolly Monkey Rediscovered in Peru Russell A

'* A Woolly Monkey Rediscovered in Peru Russell A. Mittermeier, Hernando de Macedo Ruiz, and Anthony Luscombe The Peruvian yellow-tailed woolly monkey, last seen by scientists in 1926 and feared extinct, was rediscovered by the authors in the area of the lower Andes where it was last seen. They were able to bring back a live juvenile that was being kept as a pet, and also four skins and three skulls which they got from a hunter who had shot the animals for meat. The authors urge the need to create a reserve for this rare endemic monkey in Peru and plan further exploratory trips to decide the best area. The two species of large prehensile-tailed woolly monkeys are found primarily in the Amazon basin. Lagothrix lagothricha is divided into four subspecies, all widely distributed in the rain forests of Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, all commonly exhibited in zoos, and all, until recently, frequently sold as pets. L. ftavicauda, the Peruvian yellow-tailed woolly monkey, how- ever, is restricted to a small area in Peru and occurs only in finger-like pro- jections of Amazon forest into the Andes. The rarest of New World monkeys, until last year it was known only from five museum specimens, the last collected in 1926. Scientists thought it might already be extinct. Early in 1974 we organised a brief expedition to the area where the last known specimens had been collected, and were able to obtain proof, in the form of four skins, three skulls and the first living specimen ever seen by members of the scientific community, that the monkey still existed. -

First Ornithological Inventory and Conservation Assessment for the Yungas Forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia

Bird Conservation International (2005) 15:361–382. BirdLife International 2005 doi:10.1017/S095927090500064X Printed in the United Kingdom First ornithological inventory and conservation assessment for the yungas forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia ROSS MACLEOD, STEVEN K. EWING, SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, ROSALIND BRYCE, KARL L. EVANS and AIDAN MACCORMICK Summary Bolivia holds one of the world’s richest avifaunas, but large areas remain biologically unexplored or unsurveyed. This study carried out the first ornithological inventory of one of the largest of these unexplored areas, the yungas forests of Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes. A total of 339 bird species were recorded including 23 restricted-range, four Near-Threatened, two globally threatened, one new to Bolivia and one that may be new to science. The study extended the known altitudinal ranges of 62 species, 23 by at least 500 m, which represents a substantial increase in our knowledge of species distributions in the yungas, and illustrates how little is known about Bolivia’s avifauna. Species characteristic of, or unique to, three Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs) were found. The Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes are a stronghold for yungas endemics and hold large areas of pristine Bolivian and Peruvian Upper and Lower Yungas habi- tat (EBAs 54 and 55). Human encroachment is starting to threaten the area and priority conser- vation actions, including designation as a protected area and designation as one of Bolivia’s first Important Bird Areas, are recommended. Introduction Bolivia holds the richest avifauna of any landlocked country. With a total of 1,398 species (Hennessey et al. -

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Mountains of Manu, Peru I 2019 Aug 2, 2019 to Aug 13, 2019 Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the star performers of the tour was this bold Yellow-rumped Antwren that was unusually extroverted! We may have gotten some of the best photos ever taken of this species, including this fine one by participant Becky Hansen! The Manu area of Peru is one of the world's richest sites for sheer biodiversity. The amount of life present within the park itself is astonishing, especially considering that it ranges from above treeline to the Amazon lowlands. In birds alone, it is estimated that Manu National Park contains about 1000 species! That's more than are found on several of the continents of this planet! Our tour was primarily designed to find and observe the birds that are found in the mountainous portion of the Manu area. Our tour gave us memorable views of large, showy birds such as Solitary Eagle, Hoatzin, Blue-banded Toucanet, Versicolored Barbet, among others, as well as less showy species such as the hard-to-see Amazonian Antpitta, the rare Buff-banded Tyrannulet and Yellow-rumped Antwren, and the skulking Peruvian Recurvebill. One look at the bird list will show that certainly about half of the species therein are drab and/or skulky birds that are not easily seen, but require patience and concentration... this is typical of tropical forest avifaunas anywhere in the world. Because these species usually live in understory, they are predisposed to not travel widely, and thus are highly likely to have geographic barriers fragment their distributions and render them regional specialists; many are thus endemic to the country. -

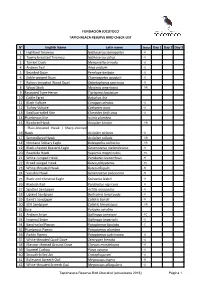

N° English Name Latin Name Status Day 1 Day 2

FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO TAPICHALACA RESERVE BIRD CHECK-LIST N° English Name Latin name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei - R 2 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius - U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata - U 4 Andean Teal Anas andium - U 5 Bearded Guan Penelope barbata - U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii - U 7 Rufous-breasted Wood Quail Odontophorus speciosus - R 8 Wood Stork Mycteria americana - VR 9 Fasciated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma fasciatum 10 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 11 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus - U 12 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura - U 13 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus - U 14 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 15 Bicolored Hawk Accipiter bicolor - VR Plain-breasted Hawk / Sharp-shinned 16 Hawk Accipiter striatus - U 17 Semicollared Hawk Accipiter collaris - VR 18 Montane Solitary Eagle Buteogallus solitarius - VR 19 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus - R 20 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris - FC 21 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous - R 22 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus - FC 23 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula - R 24 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma - R 25 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori - R 26 Blackish Rail Pardirallus nigricans - R 27 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius - R 28 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda - R 29 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii - R 30 Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus - VR 31 Sora Porzana carolina 32 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni - FC 33 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis - U 34 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas -

P0475-P0482.Pdf

NOTES ON THE PUNA AVIFAUNA OF AZ/kNGARO PROVINCE, DEPARTMENT OF PUNO, SOUTHERN PERU NICHOLAS A. ROE • AND WILLIAM E. REES Institute of Animal ResourceEcology and School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia, Vancouver,British Columbia V6T 1W5 Canada ABSTRACT.--In June 1975, we made the first dry (winter) seasonobservations of puna birds in the Province of Az•ngaro, Department of Puno, southern Peru, adding nine speciesto the avi- faunal list for the area. We observed no trochilids although they are known to be numerous during the wet (summer)season. Nesting of the Golden-spottedGround-Dove (Metriopelia aymara) is describedfor the first time from Peru, and we report the breeding on the puna of two puna species that have been recorded on the coast in the dry season.We discussaltitudinal migration to the Pacific coast during the dry season,and include a specieslist for this puna region. Received 25 April 1978, accepted4 January 1979. THE purposeof this paper is to documentsight recordsof birds made in the period 6-17 June 1975 at Hacienda Checayani,Province of Az/tngaro, Department of Puno, southern Peru. At the time we were engaged in a field study of the taruca (Hippo- camelus antisensis, Cervidae), which we have reported elsewhere (Roe and Rees 1976). Our visit occurred 14 yr after Jean Dorst visited Checayani. His articleson the avifauna there and elsewherein the Department of Puno are profuse(Dorst 1956a, b, c, d; 1957a, b; 1962a, b, c; 1963; 1972). However, Dorst's two visits to southern Peru both took place during the wet season(to which he consistentlyrefers as the breeding season) from December 1954 to March 1955 and from November 1960 to February 1961. -

Birding List

B I R D C H E C K L I S T THE MAGIC BIRDING & BIRD PHOTO CIRCUIT OF ECUADOR Checklist by: Luis Alcivar & Genesis Lopez Works Cited: BirdLife International (2004). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 10 feb 2010. Locations: Paramo and Treeline Forest: Antisana (A) - Cayambe Coca & Papallacta Pass (P) Upper Andean Forest: San Jorge Quito (Q) - Yanacocha Road (Y) Dry Inter-Andean Forest: Old Hypodrome, Pululahua Crater & Jerusalem Ecological Park (J) (Western) Andean Cloud Forest: San Tadeo Road, Santa Rosa Road, & San Jorge Tandayapa (T) (Western) Upper Tropical Forest: Umbrellabird LEK & San Jorge Milpe (M) (Western) Lower Tropical Forest: Pedro Vicente Maldonado & Silanche (V) Pacific Lowlands (Coast): San Jorge Estero Hondo & surrounding fresh water lakes (E) (Eastern) Andean Cloud Forest: Cuyuja River, Baeza, Borja, San Jorge Guacamayos, & San Jorge Cosanga (C) Upper Amazon Basin: Ollin/Narupa Reserve (O) Napo-Galeras & Sumaco National Park (S) Lower Amazon Basin (Amazon Lowlands): San Jorge Sumaco Bajo, Limoncocha Biological Reserve, Napo River & Yasuni National Park (Z) Abundance: (1) Common (2) Fairly Common (3) Uncommon (4) Rare (5) Very Rare (6) Extremely Rare > 5 observations 1 2 3 4 5 6 Endemism: N: National Endemic - Cho: Choco region (NW Ecuador and W Colombia only) - Tum: Tumbesian region (SW Ecuador and NW Peru only) E/C: Ecuador and Colombia only - (E/P) Ecuador and Peru only - (E/P/C) Ecuador, Peru & Colombia only Status: LC: Least Concern NT: Near Threatened VU: Vulnerable -

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama Master of Philosophy, Remote Sensing Bachelor of Biological Sciences (Honours) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Birds perform many types of migratory movements that vary remarkably both geographically and between taxa. Nevertheless, nomenclature and definitions of avian migrations are often not used consistently in the published literature, and the amount of information available varies widely between taxa. Although comprehensive global lists of migrants exist, these data oversimplify the breadth of types of avian movements, as species are classified into just a few broad classes of movements. A key knowledge gap exists in the literature concerning irregular, small-magnitude migrations, such as irruptive and nomadic, which have been little-studied compared with regular, long-distance, to-and- fro migrations. The inconsistency in the literature, oversimplification of migration categories in lists of migrants, and underestimation of the scope of avian migration types may hamper the use of available information on avian migrations in conservation decisions, extinction risk assessments and scientific research. In order to make sound conservation decisions, understanding species migratory movements is key, because migrants demand coordinated management strategies where protection must be achieved over a network of sites. In extinction risk assessments, the threatened status of migrants and non-migrants is assessed differently in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, and the threatened status of migrants could be underestimated if information regarding their movements is inadequate. In scientific research, statistical techniques used to summarise relationships between species traits and other variables are data sensitive, and thus require accurate and precise data on species migratory movements to produce more reliable results. -

Harms Et Al MS-526.Fm

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 17: 585–588, 2006 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS ON THE NEST AND EGG OF THE SWALLOW- TAILED NIGHTJAR (UROPSALIS SEGMENTATA SEGMENTATA) IN SOUTHEASTERN ECUADOR Inka Harms1,2, Ryan L. Lynch1, Harold F. Greeney1,3, & Rebecca Lohnes1 1Yanayacu Biological Station & Center for Creative Studies, Cosanga c/o Foch 721 y Amazonas, Quito, Ecuador. Email: [email protected] 2 Mozartstraße 14, 26434 Wangerland, Germany. Email: [email protected] Observaciones sobre el nido y huevo del Chotacabras Tijereta (Uropsalis segmentata segmentata) en el sureste del Ecuador. Key words: Nest and egg description, incubation behavior, Ecuador, Tapichalaca, Swallow-tailed Nightjar, Uropsalis segmentata. The Swallow-tailed Nightjar (Uropsalis segmen- firmed description of an egg for this species tata) is one of only two species in the genus from Ecuador. (del Hoyo et al. 1999). It ranges from Colom- On 28 September 2005, we encountered bia to Bolivia, inhabiting temperate forest the nest of a Swallow-tailed Nightjar at c. edges, clearings, and paramo on both slopes 2650 m a.s.l. in the Tapichalaca Biological of the Andes (Holyoak 2001), and is typically Reserve (04º30’S, 79º10’W), Zamora Chin- encountered at elevations between 2200 and chipe province, southeastern Ecuador. At 3600 m (Holyoak 2001, Ridgely & Greenfield 10:45 h (EST), we found a warm egg resting 2001). on the ground and, upon checking the site 45 Little is known about the breeding biol- min later, we found an incubating female ogy of the Swallow-tailed Nightjar (but see Swallow-tailed Nightjar. The bird flushed Carriker 1955, Schönwetter 1964, Hilty & rather reluctantly after being photographed Brown 1986) or its congener, the Lyre-tailed from a distance of c. -

A Prolonged Agonistic Interaction Between Two Papuan Frogmouths Podargus Papuensis

Australian Field Ornithology 2017, 34, 26–29 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo34026029 A prolonged agonistic interaction between two Papuan Frogmouths Podargus papuensis C.N. Zdenek1, 2, 3 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4067, Australia 3Address for correspondence: 15 Murrami Court, Tanah Merah QLD 4128, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract. Papuan Frogmouths Podargus papuensis are large nocturnal birds about which relatively little is known. A prolonged aggressive interaction between two Papuan Frogmouths that involved interlocking beaks was filmed in the Lockhart River region on Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, and is described here. Two additional Papuan Frogmouths were present during the event, one of which gave a call-type (OomWoom) previously unrecorded for this species. Difficulties associated with detecting such agonistic behaviour mean that the prevalence of these contests and their behavioural significance are currently unknown and require further research. Introduction Study area and methods Conflict between conspecifics can be motivated by On 19 August 2015, the observation was recorded at 1856 h territorial dispute, competition for mates, and/or competition in the Lockhart River region on Cape York Peninsula, for resources (West-Eberhard 1983; Begon et al. 2006). Queensland (12°47′S, 143°18′E) (Figure 1). The following Many species have appendages of different forms that equipment was used to film the event: a Canon EOS 5D are used as weapons (e.g. horns, antlers, mandibles) to Mark III camera with a 400-mm (fixed) EF f5.6L IS USM lens secure territories and attract mates (Clutton-Brock & Albon and a directional Rode VideoMic pro external microphone 1979; Kelly 2006), but weaponry is largely absent in birds, (with a windshield; set to 0 dB gain boost). -

Long-Trained Nightjar (Macropsalis Forcipata) (Aves, Caprimulgidae): first Paraguayan Record

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 22(4), 413-415 SHORTCOMMUNICATION December 2014 Long-trained Nightjar (Macropsalis forcipata) (Aves, Caprimulgidae): first Paraguayan record Hans Hostettler1 and Paul Smith2, 3 1 Procosara (Pro Cordillera San Rafael), Municipalidad de Alto Vera, Itapúa, Paraguay. 2 Fauna Paraguay, Encarnación, Paraguay. www.faunaparaguay.com & Para La Tierra, Reserva Natural Laguna Blanca, Santa Rosa del Aguaray, San Pedro, Paraguay. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 3 November 2014. Accepted on 9 November 2014. ABSTRACT: The first observations of Long-trained NightjarMacropsalis forcipata in Paraguay are documented, confirming speculation that the species was likely to occur in the country. KEYWORDS: Atlantic Forest, Caprimulgiformes, distribution, range expansion, Paraguay. The Long-trained Nightjar Macropsalis forcipata is the bird repeatedly returned to the exact same spot after endemic to the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil being flushed, as noted by Bodrati & Cockle (2012). Such (Espirito Santo to Rio Grande do Sul) and Misiones behaviour has been associated with the establishment Province in northeastern Argentina (Cleere 1999, Cleere of display arenas to which males are faithful (Olmos & & Nurney 1998). The species was first documented Rodrigues 1990). for Argentina in 1973 (Olrog 1973), but on the basis To date this is the only observation of this species of numerous recent records across Misiones Province in Paraguay and because only a single male was seen it it has been suggested that it is in expansion, facilitated is impossible to draw any firm conclusions on the status by human alteration of native forest and that records in of the species in the country. However the distance of neighbouring Paraguay should be expected (Bodrati & 79.7 km from the closest Argentine locality (San Martín, Cockle 2012). -

Proposals 2011-B

N&MA Classification Committee: Proposals 2011-B No. Page Title 01 2 Recognize Baird’s Junco Junco bairdii as a distinct species 02 4 Rearrange the sequence of species in the genus Spizella 03 6 Split Caprimulgus into multiple genera 04 10 Rearrange the linear sequence of genera in the Furnariidae (SACC proposal # 504) 05 12 Revise limits of Buteogallus and Leucopternis (SACC proposals # 459, 460, 492) 06 14 Treat Basileuterus hypoleucus as conspecific with Basileuterus culicivorus (SACC proposal # 493) 07 18 Change linear sequence of orders for Falconiformes and Psittaciformes (SACC proposal # 491A) 08 20 Add European Golden-Plover Pluvialis apricaria to the US list 09 21 Change name of the family Pteroclididae (sandgrouse) to Pteroclidae 2011-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 626 Recognize Baird’s Junco (Junco bairdii) as a distinct species Baird’s Junco (Junco bairdi) Belding 1883. Victoria Mts., Lower California. Description of the problem: Restricted to the mountains of the Cape Region of Baja California, Baird’s Junco (Junco bairdi Belding 1883: Victoria Mts., Lower California) was treated as a separate species at least as late as the 5th edition of the AOU Check-list (1957). Note that A. H. Miller was on that committee; Miller, in his monograph (1941) considered it a separate species, along with many other “subspecies” of Yellow- eyed Juncos. Paynter (1970) considered it a subspecies of the Yellow-eyed Junco (J. phaeonotus bairdi) Ridgway (ex. Belding MS) 1883, and the 6th edition of the AOU Check-list (1983) followed this treatment. Howell & Webb, in their Birds of Mexico (1995), considered it a separate species.