Carl Nielsen and the Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a R L N I E L S E N S T U D I

CARL NIELSEN STUDIES V O L U M E V I • 2 0 2 0 CARL NIELSEN STUDIES V O L U M E V I • 2 0 2 0 Edited by Michelle Assay, David Fanning (editor-in-chief), Daniel Grimley, Niels Krabbe (consultant), and Christopher Tarrant Copenhagen 2020 The Royal Library Honorary board John Bergsagel, prof.emer., Copenhagen Jean Christensen, prof., University of Louisville, Kentucky Ludwig Finscher, prof.emer., Wolfenbüttel Jim Samson, prof., Royal Holloway, London Arnold Whittall, prof.emer., King’s College, London Editorial board Michelle Assay David Fanning (editor-in-chief) Daniel Grimley Niels Krabbe (consultant) Christopher Tarrant Translation or linguistic amendment of texts by Eskildsen, Røllum-Larsen, and Caron has been carried out by David Fanning, Marie-Louise Zervides, and Michelle Assay. Graphic design Kontrapunkt A/S, Copenhagen Layout and formatting Hans Mathiasen Text set in Swift ISSN 1603-3663 Sponsored by The Carl Nielsen and Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen Foundation © 2020 The authors and Carl Nielsen Studies, The Royal Library All rights reserved 2020 Permission for the use of quotations from the Carl Nielsen Edition has been kindly given by The Royal Library. R eports After the publication of the last volume The 150th anniversary of Nielsen’s of The Carl Nielsen Edition (CNU) prop- birth was celebrated intensively, both er in 2009, two further projects were in Denmark and in many places abroad, launched, one of which is finished, while with concerts, performance of the two the other is still at the planning stage. At operas at the Royal Theatre, Nielsen as the request of the jury of the chamber featured composer at the BBC London music competition in 2015 (see below), Proms, festivals, books and CD publica- a volume with an annotated facsimile tions, etc. -

Carl Nielsen Studies 3 (2008)

BIBLIOGRAPHY CARL NIELSEN BIBLIOGRAPHY 2004-2007 By Kirsten Flensborg Petersen Bubert, Dennis: ‘Orchestral Excerpt Class’, ITA Journal 31:4 (2003) pp. 20-22. The bibliographies published in Carl Niel- sen Studies – including the following Carl Nielsen brevudgaven [The Letters of bibliography – are also to be found on Carl Nielsen], John Fellow (ed.), Køben- the internet at www.kb.dk/da/kb/nb/mta/ havn 2005-, volume 1, 1886-1897, Køben- cnu/studies.html. havn 2005, 571 p. Anderson, Martin: ‘Thomas Dausgaard: Carl Nielsen brevudgaven [The Letters of Conductor in a hurry’, Nordic Sounds 4 Carl Nielsen], John Fellow (ed.), Køben- (2003) pp. 9-13. havn 2005-, volume 2, 1898-1905, Køben- havn 2006, 598 p. Austen, Jill: ‘Behind ‘The Mother’’, Flutist Quarterly – The Official Magazine of the Carl Nielsen brevudgaven [The Letters of National Flute Association 30/4 (2005) pp. Carl Nielsen], John Fellow (ed.), Køben- 46-48. havn 2005-, volume 3, 1906-1910, Køben- havn 2007, 589 p. Benestad, Finn and Dag Schjelderup-Ebbe: ‘To åndsbeslektede tonemestre: Johan Carl Nielsens Barndomshjem 1956-2006: Jubi- Svendsen og Carl Nielsen’ [Two spiritu- læumsskrift [Carl Nielsen’s home 1956- ally related masters: Johan Svendsen and 2006: Jubilee publication], Nr. Lyndelse Carl Nielsen], in Musikvidenskabelige Kom- 2006, 16 p. positioner: Festskrift til Niels Krabbe 1941 – 3. oktober – 2006, Anne Ørbæk Jensen et Chandler, Beth E.: The ‘Arcadian’ flute: Late al. (eds.), København 2006, pp. 425-436. style in Carl Nielsen’s works for flute, diss., University of Cincinnati 2004, 168 p. Brown, Peter: The symphonic repertoire. Vol. 3. Part A, The European symphony from ca Christensen, Erik: ‘Danish music: The 1800 to ca 1930: Germany and the Nordic transition from tradition to modernism’, Countries, Bloomington 2007, 1168 p. -

UCLA Symphony Programs 2005-2019

UCLA SYMPHONY 2005 - 2019 November 30, 2005 Haydn Symphony No. 88 Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 102 Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, Op. 17 (Little Russian) Neal Stulberg, conductor and pianist Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 6, 2006 Stravinsky Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra Mozart Clarinet Concerto, K. 622 Beethoven Symphony No. 1, Op. 21 Denexxel Domingo, clarinet Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * June 9, 2006 Fauré Suite from Pélléas et Mélisande Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Op. 33 Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade, Op. 35 Isaac Melamed, cello John Carter and Daniel Cummings, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * November 29, 2006 Bernstein Overture to Candide Haydn Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello, Oboe and Bassoon, Op. 84 Puccini Preludio Sinfonico Liszt Les Préludes (Symphonic Poem No. 3) Mary Hofman, violin Isaac Melamed, cello Michelle An, oboe Amy Gillick, bassoon Daniel Cummings, Georgios Kountouris, Neal Stulberg, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 14, 2007 DANCE PARTY! Dvorak Slavonic Dance No. 7 in C major, Op. 72 Saint-Saens Danse Macabre, Op. 40 Falla Ritual Fire Dance from El Amor Brujo Piazzolla Tangazo Tchaikowsky Three Dances from Swan Lake Debussy Danse Sacrée et Danse Profane for harp and strings Glière Russian Sailors' Dance from The Red Poppy Copland Hoedown from Rodeo Sousa Hands Across the Sea Lindsay Strand-Polyak, violin Jacque Marshall, harp Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * May 30, 2007 Mozart Symphony No. 35 (Haffner), K. 385 Ney Rosauro Concerto for Marimba and String Orchestra Moussorgsky/Ravel Pictures from an Exhibition Jamie Strowbridge, marimba Daniel Cummings and Georgios Kountouris, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA December 5, 2007 Mozart Overture to Don Giovanni Rheinberger Concerto for Organ No. -

A CN 34 Orkester Tekst 01 1 03/12/04, 15:27 C ARL NIELSEN

C ARL NIELSEN V ÆRKER W ORKS Carl Nielsen Udgaven CN 00034 i A CN 34 orkester tekst 01 1 03/12/04, 15:27 C ARL NIELSEN 1 865-1931 V ÆRKER W ORKS Udgivet af Carl Nielsen Udgaven Det Kongelige Bibliotek Hovedredaktør Niels Krabbe Serie II. Instrumentalmusik. Bind 8 Published by The Carl Nielsen Edition The Royal Library Editor in chief Niels Krabbe Series II. Instrumental Music. Volume 8 Edition Wilhelm Hansen Copenhagen 2004 Carl Nielsen Udgaven CN 00034 ii A CN 34 orkester tekst 01 2 03/12/04, 15:27 C ARL NIELSEN ORKESTERVÆRKER 2 ORCHESTRAL WORKS 2 Udgivet af Edited by Niels Bo Foltmann Peter Hauge Edition Wilhelm Hansen Copenhagen 2004 Carl Nielsen Udgaven CN 00034 iii A CN 34 orkester tekst 01 3 03/12/04, 15:27 Orchestral parts are available Graphic design Kontrapunkt A/S, Copenhagen Music set in SCORE by New Notations, London Text set in Swift Printed by Quickly Tryk A/S, Copenhagen CN 00034 ISBN 87-598-1127-7 ISMN M-66134-113-0 Sponsored by Vera og Carl Johan Michaelsens Legat Distribution Edition Wilhelm Hansen A/S, Bornholmsgade 1, DK-1266 Copenhagen K Translation James Manley © 2004 Carl Nielsen Udgaven, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, København All rights reserved 2004 Carl Nielsen Udgaven CN 00034 iv A CN 34 orkester tekst 01 4 03/12/04, 15:27 INDHOLD C ONTENTS General Preface vii Generelt forord Preface xi Forord Facsimiles xxxiii Faksimiler SAGA DREAM, OPUS 39 1 SAGA-DRØM, OPUS 39 AT THE BIER OF A YOUNG ARTIST 23 VED EN UNG KUNSTNERS BAARE FOR STRING ORCHESTRA FOR STRYGEORKESTER ANDANTE LAMENTOSO ANDANTE LAMENTOSO NEARER MY GOD TO -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

Carl Nielsen's Quintet for Winds, Op. 43: a Critical Edition

CARL NIELSEN'S QUINTET FOR WINDS, OP. 43: A CRITICAL EDITION, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS FOR HORN BY ATTERBERG, RIES, MOZART, ROSETTI, MUSGRAVE, LARSSON, AND OTHERS Marcia L. Spence, B.M., M.M., M.B.A. APPROVED: Major Professor Minor rofessor Committee eiber Committee Member Dean of the College of Music Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies ONA1If CARL NIELSEN'S QUINTET FOR WINDS, OP. 43: A CRITICAL EDITION, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS FOR HORN BY ATTERBERG, RIES, MOZART, ROSETTI, MUSGRAVE, LARSSON, AND OTHERS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Marcia L. Spence, B.M., M.M., M.B.A. Denton, Texas December, 1995 Spence, Marcia Louise, Carl Nielsen's Quintet for Winds, Op. 43: A Critical Edition, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works for Horn by Atterberg, Ries, Mozart, Rosetti, Musgrave, Larsson, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December, 1995, 143 pp., 14 examples, 3 appendices, bibliography, 29 titles. The purpose of this dissertation is to prepare and present a critical edition of Carl Nielsen's Quintet fbr Winds, Op. 43, a major work in the woodwind quintet repertoire. Written for the Copenhagen Wind Quintet in 1922, it is also considered a pivotal composition in Nielsen's artistic output. The only published edition of this piece, by Edition Wilhelm Hansen, is rife with errors, a consistent problem with many of Nielsen's compositions. -

Chandos Records Ltd, Chandos House, Commerce Way, Colchester, Essex CO2 8HQ, UK E-Mail: [email protected] Website

CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 Book Cover.qxd 7/2/07 1:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 10271(3) X CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) COMPACT DISC ONE Symphony No. 1, Op. 7, FS 16 37:01 in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur 1 I Allegro orgoglioso 10:07 2 II Andante 8:23 3 III Allegro comodo – Andante sostenuto – Tempo I 8:45 4 IV Finale. Allegro con fuoco 9:43 Symphony No. 4, Op. 29, FS 76 ‘The Inextinguishable’ 37:04 Roland Johansson • Lars Hammarteg timpani soloists 5 I Allegro – 11:52 6 II Poco allegretto – 4:59 7 III Poco adagio quasi andante – 10:29 8 IV Allegro – Glorioso – Tempo giusto 9:43 TT 74:13 COMPACT DISC TWO Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29 Department of Copenhagen Library, The Royal Prints and Photographs, Maps, ‘The Four Temperaments’ 35:32 1 I Allegro collerico 10:30 2 II Allegro comodo e flemmatico 5:26 3 III Andante malincolico 12:14 Carl Nielsen 4 IV Allegro sanguineo – Marziale 7:20 3 CHAN 10271 BOOK.qxd 7/2/07 1:14 pm Page 4 Symphony No. 3, Op. 27, FS 60 Symphony No. 6, FS 116 ‘Sinfonia espansiva’ 42:02 ‘Sinfonia semplice’ 34:52 Solveig Kringelborn soprano 7 I Tempo giusto – Allegro passionato – Karl-Magnus Fredriksson baritone Lento ma non troppo – Tempo I (giusto) 13:12 5 I Allegro espansivo 12:44 8 II Humoreske. -

Nielsen Flute Concerto Clarinet Concerto Aladdin Suite

SIGCD477_BookletFINAL*.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 22/12/2016 13:24 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. Also available… NIELSEN FLUTE CONCERTO CLARINET CONCERTO 1 1 3 6 4 4 ALADDIN SUITE D D C C G G I I S S SAMUEL COLES FLUTE Bruckner: Symphony No.9 Schubert: Symphony No.9 Philharmonia Orchestra Philharmonia Orchestra MARK VAN DE WIEL CLARINET Christoph von Dohnányi Christoph von Dohnányi SIGCD431 SIGCD461 PAAVO JÄRVI “Beautifully prepared account ... Dohnányi’s new recording "This performance ... goes for broke and succeeds, to the is distinguished by the clarity with which it presents evident rapture of the audience. The Philharmonia is up to Bruckner’s score as well as the excellence of its sound.” all Dohnanyi's and Schubert's steep demands, and I was left Gramophone with a feeling of exhausted exhilaration." BBC Music Magazine Flute Concerto Producer – Andrew Cornall recorded live at Royal Festival Hall, 19 November 2015 Engineer – Jonathan Stokes Editor, Mixing & Mastering – Jonathan Stokes Clarinet Concerto Cover Image – Shutterstock recorded live at Royal Festival Hall, 19 May 2016 Design – Darren Rumney Aladdin Suite P2017 Philharmonia Orchestra recorded at Henry Wood Hall, 20 May 2016 C2017 Signum Records 20 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD477_BookletFINAL*.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 22/12/2016 13:24 Page 23 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. PAAVO JÄRVI CARL NIELSEN 1865-1931 reflection and prettiness. 15 years had passed NIELSEN Flute Concerto since the first performance of Nielsen’s Violin PaavFo LJäUrvTi iEs cCurrOenNtlyC CEhiRefT COonductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra, Artistic Director of the Concerto when the Flute Concerto was DeutCschLeA KRamImNeErpThi lChaOrmNonCie EanRdT thOe founder of the Estonian Festival Orchestra, which brings Allegro moderato introduced in Paris in 1927. -

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, As Posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson Is Clarinetist with the Lightwood Duo, an Actively Touring Clarinet/Guitar Duo

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, as posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson is clarinetist with The Lightwood Duo, an actively touring clarinet/guitar duo. Their CDs are available through their website, http://www.lightwoodduo.com. About two weeks ago, there were some questions about Aage Oxenvad on the list. Having studied Nielsen and clarinet at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen [in 1979], I would like to pass on some first-hand information on Oxenvad. There are two major obstacles to acquiring accurate information about Danish music. First, much of the info exists only in the Danish language; not exactly a familiar language to most. Second, the Danes are not inclined to value the sharing of such information. To quote Tage Scharff, the clarinet professor with whom I studied: "You Americans [and English as well] love to get together and give lectures, deliver papers, and hold conferences. Here in Denmark, vi spiller! [we PLAY]". He was quite amused that I, a performing clarinetist, would be so interested in such material. On a posting on this list, Jarle Brosveet wrote: "In the first place Oxenvad did not inspire Nielsen to write the concerto, although he was the first to perform it. It was written at the request of Nielsen's benefactor and one-time student Carl Johan Michaelsen. Second, Oxenvad, who is described as a choleric, made this unflattering remark about Nielsen and the concerto: "He must be able to play the clarinet himself, otherwise the would hardly have been able to find the worst notes to play." Oxenvad performed it on several occasions with no apparent success although he reportedly did all he could, whatever that is supposed to mean. -

NORDIC COOL 2013 Feb. 19–Mar. 17

NORDIC COOL 2013 DENMARK FINLAND Feb. 19–MAR. 17 ICELAND NorwAY SWEDEN THE KENNEDY CENTER GREENLAND THE FAroE ISLANDS WASHINGTON, D.C. THE ÅLAND ISLANDS Nordic Cool 2013 is presented in cooperation with the Nordic Council of Ministers and Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Presenting Underwriter HRH Foundation Festival Co-Chairs The Honorable Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Marilyn Carlson Nelson, and Barbro Osher Major support is provided by the Honorable Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Mrs. Marilyn Carlson Nelson and Dr. Glen Nelson, the Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation, David M. Rubenstein, and the State Plaza Hotel. International Programming at the Kennedy Center is made possible through the generosity of the Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts. NORDIC COOL 2013 Perhaps more so than any other international the Faroe Islands… whether attending a performance festival we’ve created, Nordic Cool 2013 manifests at Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theatre (where Ingmar the intersection of life and nature, art and culture. Bergman once presided), marveling at the exhibitions in Appreciation of and respect for the natural environment the Nobel Prize Museum, or touring the National Design are reflected throughout the Nordic countries—and Museum in Helsinki (and being excited and surprised at they’re deeply rooted in the arts there, too. seeing objects from my personal collection on exhibit there)… I began to form ideas and a picture of the The impact of the region’s long, dark, and cold winters remarkable cultural wealth these countries all possess. (sometimes brightened by the amazing light of the , photo by Sören Vilks Sören , photo by aurora borealis). -

A Musical Weekend in Washington a Musical Weekend in Washington WALTER B

Lundgren,: A Musical Weekend in Washington A Musical Weekend in Washington WALTER B. RUDOLPH B. WALTER By Janel E. Lundgren, Editor WALTER B. RUDOLPH B. WALTER MARILYN RUDOLPH MARILYN Members and friends at one of the JBS tables in the Roof Terrace Restaurant, Kennedy Center “It was a wonderful idea to bring JB Society members together for an outstanding performance with the National Symphony Orchestra with such great singers. The dinner at the Kennedy Center was quite enjoyable, met some interesting people and had a good time. “The Jussi Björling Society USA is quite a wonder. Its activities and discoveries and publications preserve our cherished memories of the great Jussi, and I hope it will continue to thrive.” —JBS Member Robert Schreiber November, 2019 embers of the Board of JBS-USA event, and in the end, we arranged for a enjoyed another weekend in block of 25 seats for the Friday, November Washington D.C.. November 15 15th concert performance of Act II, Tristan Mto 17, 2019, devoted to an annual board und Isolde, by the National Symphony meeting, musical events, and friendship. An Orchestra. open invitation was extended to JBS mem- The evening started with dinner reser- bers and friends, board members of Vocal vations for all in the Roof Terrace Restau- Arts DC, and representatives of the Swedish rant of the Kennedy Center. At dinner, it Embassy to join us for a Friday evening was an extra treat to have the opportunity 28 v February 2020 Journal of the Jussi Björling Society – USA, Inc. www.jussibjorlingsociety.org Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2020 1 Journal of the Jussi Björling Societies of the USA & UK, Vol. -

Carl Nielsen, C

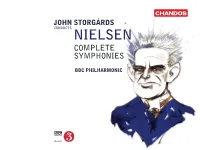

JOHN STORGÅRDS CONDUCTS NIELSEN COMPLETE SYMPHONIES BBC PHILHARMONIC Carl Nielsen, c. 1925 Carl Nielsen,c. © Scanpix / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Carl Nielsen (1865 – 1931) COMPACT DISC ONE Symphony No. 1, Op. 7, FS 16 (1891 – 92)* 33:20 in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur 1 I Allegro orgoglioso – Poco meno mosso – Molto tranquillo – Assai più vivo del Tempo I – Tempo I – A tempo, ma un poco sostenuto – Molto tranquillo – Allegro molto – Stretto 9:35 2 II Andante – Tranquillo 6:28 3 III Allegro comodo – Risoluto – Andante sostenuto – Tempo I (Allegro) – Andante sostenuto – Molto tranquillo – Allegro assai 8:00 4 IV Finale. Allegro con fuoco – Poco tranquillo – Più vivo – Tempo I – Poco tranquillo – Allegro molto 9:01 3 Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29 ‘The Four Temperaments’ (1901 – 02)* 33:09 (De fire Temperamenter) 5 I Allegro collerico – A tempo ma tranquillo – Poco moto – Tempo I – Brioso – A tempo ma molto tranquillo – Poco più (stretto) 9:47 6 II Allegro comodo e flemmatico 4:12 7 III Andante malincolico – Poco largamente – Tempo I – Un pochettino più mosso – Tempo I 11:56 8 IV Allegro sanguineo – Adagio molto – Tempo I – Marziale 6:58 TT 66:44 COMPACT DISC TWO Symphony No. 3, Op. 27, FS 60 ‘Sinfonia espansiva’ (1910 – 11)*† 37:57 1 I Allegro espansivo – Molto tranquillo – Un pochettino meno – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Tranquillo 12:31 2 II Andante pastorale – A tempo, tranquillo – Un poco di più animato – Tempo I, ma molto tranquillo – Adagio – Tranquillo 9:05 3 III Allegretto un poco – [ ] – Tempo I – Tranquillo 6:31 4 IV Finale.