The Ups and Downs of Head Displacement Karlos Arregi Asia Pietraszko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico State University

Financial Report Table of Contents Financial Statements and Schedules June 30, 2010 and 2009 Official Roster........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 President’s Letter .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Independent Auditor’s Report ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Financial Statements Management’s Discussion and Analysis ............................................................................................................................... 5 Exhibit A: Statement of Net Assets ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Exhibit B: Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets ........................................................................ 17 Exhibit C: Statement of Cash Flows .................................................................................................................................... 19 Notes to the Financial Statements ...................................................................................................................................... 21 Supplemental Schedules Schedule 1 - Combining Statement of Net Assets for -

Cliff Notes: Research in Natural Language Processing at the University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Technical Reports (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science March 1992 CLiFF Notes: Research In Natural Language Processing at the University of Pennsylvania Faculty & Graduate Students University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports Recommended Citation Faculty & Graduate Students, "CLiFF Notes: Research In Natural Language Processing at the University of Pennsylvania", . March 1992. University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science Technical Report No. MS-CIS-92-22. Edited by Barbara Di Eugenio and Libby Levison. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/480 For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLiFF Notes: Research In Natural Language Processing at the University of Pennsylvania Abstract The Computational Linguistics Feedback Forum (CLIFF) is a group of students and faculty who gather once a week to discuss the members' current research. As the word "feedback" suggests, the group's purpose is the sharing of ideas. The group also promotes interdisciplinary contacts between researchers who share an interest in Cognitive Science. There is no single theme describing the research in Natural Language Processing at Penn. There is work done in CCG, Tree adjoining grammars, intonation, statistical methods, plan inference, instruction understanding, incremental interpretation, language acquisition, syntactic parsing, causal reasoning, free word order languages, ... and many other areas. With this in mind, rather than trying to summarize the varied work currently underway here at Penn, we suggest reading the following abstracts to see how the students and faculty themselves describe their work. Their abstracts illustrate the diversity of interests among the researchers, explain the areas of common interest, and describe some very interesting work in Cognitive Science. -

Peter Culicover's Curriculum Vitae, 2019-20

CURRICULUM VITAE June 2020 PETER W. CULICOVER Distinguished University Professor Emeritus, The Ohio State University Affiliate Professor, University of Washington Phone (cell): 614-361-4744 Email: [email protected] Primary research interests: Syntactic theory, constructions, typology, syntactic change, language learnability, English syntax, representation of language in the mind/brain, linguistics and cognitive science, computational simulation of language acquisition and language change, jazz. EDUCATION PhD Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1971), Linguistics B.A. City College of NeW York (1966), Mathematics ACADEMIC POSITIONS HELD 2019- Affiliate Professor, University of Washington 2018- Distinguished University Professor Emeritus, OSU 2016-2018 Distinguished University Professor, The Ohio State University 2008 Professeur invité, Université de Paris VII (Feb-Mar 2008) 2006-7 Visiting Scholar, Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Tübingen 2005- Humanities Distinguished Professor in Linguistics, The Ohio State University 2003 Linguistics Institute, Michigan State University (Summer 2003) 2002 Visiting Scientist, University of Groningen (Autumn 2002) 2000 Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Tübingen (June 2000) 1998-2006 Chair, Department of Linguistics, The Ohio State University 1997 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Theoretical Linguistics, University of Venice (Spring 1997) 1991-92 Visiting Scientist, Center for Cognitive Science, MIT 1989-2003 Director, Center for Cognitive Science, The Ohio State University -

Bulletin - December 2001 Page 1 of 48

LSA Bulletin - December 2001 Page 1 of 48 Bulletin No. 174, December 2001 Copyright ©2001 by the Linguistic Society of America Linguistic Society of America 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211 Washington, DC 20036-6501 [email protected] The LSA Bulletin is issued a minimum of four times per year by the Secretariat of the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501 and is sent to all members of the Society. News items should be addressed to the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. All materials must arrive at the LSA Secretariat by the 1st of the month preceding the month of publication. Annual dues for U.S. personal memberships for 2000 are $65.00; U.S. student dues are $25.00 per year, with proof of status; U.S. library memberships are $120.00; add $10.00 postage surcharge for non-U.S. addresses; $13.00 of dues goes to the publication of the LSA Bulletin. New memberships and renewals are entered on a calendar year basis only. Postmaster: Send address changes to: Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. CONTENTS z LSA Presidents z Constitution of the Linguistic Society of America z LSA Officers and Executive Committee - 2002 z LSA Committees - 2002 z LSA Delegates and Liaisons - 2002 z Honorary Members z Language Online z Language Style Sheet z Model Abstracts z 2002 Abstract Submittal Form: 15 - and 30 - Minute Papers and Poster Sessions { Download rtf file z Program Committee 2002 Guidelines and Abstract Specifications z Grants Calendar z Grant Agency Addresses z LSA Guidelines for Nonsexist Usage z Forthcoming Conferences z Job Opportunities z Prizes Awarded by the LSA LSA PRESIDENTS 1925 Hermann Collitz (1855-1935) 1963 Mary R. -

Bulletin Page 1 of 1

December 2004 Bulletin Page 1 of 1 Bulletin No. 186, December 2004 Copyright ©2004 by the Linguistic Society of America Linguistic Society of America 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211 Washington, DC 20036-6501 [email protected] The LSA Bulletin (ISSN 0023-6365) is issued four times per year (March, June, October, and December) by the Secretariat of the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501 and is sent to all members of the Society. News items should be addressed to the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. All materials must arrive at the LSA Secretariat by the 1st of the month preceding the month of publication. Periodical postage is paid at Washington, DC, and at additional mailing offices. Annual dues for U.S. personal members for 2004 are $65.00; U.S. student dues are $25.00 per year, with proof of status; U.S. library memberships are $120.00; add $10.00 postage surcharge for non-U.S. addresses; $13.00 of dues goes to the publication of the LSA Bulletin. New memberships and renewals are entered on a calendar year basis only. Postmaster: Send address changes to: LSA Bulletin, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. Electronic mail: [email protected]. CONTENTS z LSA Officers and Executive Committee - 2005 z LSA Committees - 2005 z LSA Delegates and Liaisons - 2005 z Abstract Specifications LSA Homepage http://lsadc.org/info/dec04bulletin/indextext.html 5/21/2008 December 2004 LSA Bulletin - Abstract Specifications Page 1 -

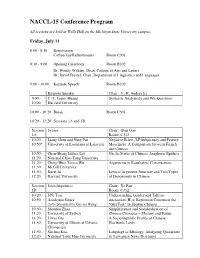

Conference Program

NACCL-15 Conference Program All sessions are held at Wells Hall on the Michigan State University campus. Friday, July 11 8:00 - 8:30 Registration Coffee/Tea/Refreshments Room C301 8:30 - 9:00 Opening Ceremony Room B102 Dr. Wendy Wilkins, Dean, College of Arts and Letters Dr. David Prestel, Chair, Department of Linguistics and Languages 9:00 - 10:00 Keynote Speech Room B102 Keynote Speaker Chair: Y.-H. Audrey Li 9:00 - C.-T. James Huang Syntactic Analyticity and Wh-Questions 10:00 Harvard University 10:00 - 10:20 Break Room C301 10:20 - 12:20 Sessions 1A and 1B Session Syntax Chair: Qian Gao 1A Room: C313 10:20 - Liang Chen and Ning Pan Negative Effect, LF Subjacency and Feature 10:50* University of Louisiana at Lafayette Movement: A Comparison between French and Chinese 10:50 - Chen-Sheng Luther Liu On the Status of Chinese Anaphoric Epithets 11:20 National Chiao Tung University 11:20 - Ching-Huei Teresa Wu Arguments in Resultative Constructions 11:50 McGill University 11:50 - Ruixi Ai Lexical Argument Structure and Two Types 12:20 Harvard University of Denominals in Chinese Session Sociolinguistics Chair: Ye Fan 1B Room: C312 10:20 - I-Ni Tsai Understanding Gender and Talk-in- 10:50 Academia Sinica interaction: How Repetition Constructs the (to be presented by Cui-xia Weng) "Girl Talk" in Spoken Chinese 10:50 - Shouhui Zhao Simplification and Standardization of 11:20 University of Sydney Chinese Character -- History and Future 11:20 - Liwei Gao A Sociolinguistic Profile of Chinese 11:50 University of Illinois at Urbana- Electronic Lexis -

Bulletin LSA PRESIDENTS

LSA October 2000 Bulletin Page 1 of 34 Bulletin No. 170, December 2000 Copyright ©2000 by the Linguistic Society of America Linguistic Society of America 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211 Washington, DC 20036-6501 [email protected] The LSA Bulletin is issued a minimum of four times per year by the Secretariat of the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501 and is sent to all members of the Society. News items should be addressed to the Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. All materials must arrive at the LSA Secretariat by the 1st of the month preceding the month of publication. Annual dues for U.S. personal memberships for 2000 are $65.00; U.S. student dues are $25.00 per year, with proof of status; U.S. library memberships are $120.00; add $10.00 postage surcharge for non-U.S. addresses; $13.00 of dues goes to the publication of the LSA Bulletin. New memberships and renewals are entered on a calendar year basis only. Postmaster: Send address changes to: Linguistic Society of America, 1325 18th Street, NW, Suite 211, Washington, DC 20036-6501. CONTENTS z LSA Presidents z Constitution of the Linguistic Society of America z LSA Officers and Executive Committee - 2001 z LSA Committees - 2001 z LSA Delegates and Liaisons - 2001 z Honorary Members z Program Committee 2001 Guidelines and Abstract Specifications z 2001 Abstract Submittal Form: 15- and 30-minute papers and poster sessions z Model Abstracts z Grants Calendar z Grant Agency Addresses z Forthcoming Conferences z LSA Guidelines for Nonsexist Usage z Job Opportunities LSA Homepage LSA PRESIDENTS 1925 Hermann Collitz (1855-1935) 1963 Mary R.