1906 January

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barn G Stables 57-78 on Account of SMYTZER's LODGE, Gnarwarre

Barn G Stables 57-78 On Account of SMYTZER'S LODGE, Gnarwarre. Lot 281 BAY COLT 10 (Branded nr sh. 4 off sh. Foaled 12th November, 2004.) Danehill........................... by Danzig ....................... (SIRE) Danehill Dancer (Ire) ...... Mira Adonde ................... by Sharpen Up ................ CHOISIR....................... Lunchtime (GB) .............. by Silly Season ............... Great Selection ............... Pensive Mood.................. by Biscay........................ (DAM) Hethersett........................ by Hugh Lupus ............... Blakeney......................... PERCY'S GIRL (IRE).. Windmill Girl.................. by Hornbeam .................. 1988 Sassafras.......................... by Sheshoon.................... Laughing Girl.................. Violetta ........................... by Pinza.......................... By CHOISIR (Ch., 1999) Champion 2YO Colt 2001/02, 3YO Sprinter 2002/03; won 7 races and $2,230,033 inc. Royal Ascot Golden Jubilee S. Gr 1, VRC Lightning S. Gr 1, Royal Ascot King's Stand S. Gr 2, VRC Emirates Classic Gr 2. 2d Newmarket July Cup Gr 1, AJC Sires' Produce S. Gr 1. 3d STC Golden Slipper S. Gr 1, MRC Caulfield Guineas Gr 1, AJC Champagne S. Gr 1, MRC Oakleigh P. Gr 1; his oldest progeny are yearlings. 1st DAM Percy's Girl (Ire), by Blakeney. 2 wins at 1¼m., 10½f. inc. Sandown Mitre Graduation S. 2d Ayr Doonside Cup L, York Galtres S. L. 4th Newmarket Godolphin S. L. Sister to PERCY'S LASS (dam of SIR PERCY, Blue Lion). Half-sister to BRAISWICK (dam of ICKLINGHAM). This is her ninth foal. Her eighth foal is a 2YO, 4 raced, 3 winners- MISS CORINNE (f by Mark Of Esteem). 5 wins 1500 to 2350m. in Italy. BYSSHE (f by Linamix). 2 wins at 2400, 2600m. in France. PERCY ISLE (c by Doyoun). 1 win at 1½m. -

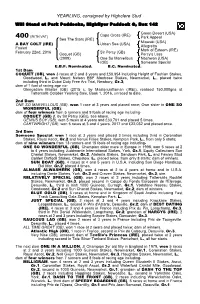

YEARLING, Consigned by Highclere Stud

YEARLING, consigned by Highclere Stud Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock G, Box 142 Green Desert (USA) Cape Cross (IRE) 400 (WITH VAT) Park Appeal Sea The Stars (IRE) Miswaki (USA) A BAY COLT (IRE) Urban Sea (USA) Allegretta Foaled Mark of Esteem (IRE) February 22nd, 2016 Sir Percy (GB) Coquet (GB) Percy's Lass (2009) One So Marvellous Nashwan (USA) (GB) Someone Special E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st Dam COQUET (GB), won 3 races at 2 and 3 years and £50,954 including Height of Fashion Stakes, Goodwood, L. and Mount Nelson EBF Montrose Stakes, Newmarket, L., placed twice including third in Dubai Duty Free Arc Trial, Newbury, Gr.3; dam of 1 foal of racing age viz- Glencadam Master (GB) (2015 c. by Mastercraftsman (IRE)), realised 150,000gns at Tattersalls October Yearling Sale, Book 1, 2016, unraced to date. 2nd Dam ONE SO MARVELLOUS (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed once; Own sister to ONE SO WONDERFUL (GB); dam of four winners from 5 runners and 9 foals of racing age including- COQUET (GB) (f. by Sir Percy (GB)), see above. GENIUS BOY (GB), won 5 races at 4 years and £33,701 and placed 5 times. CARTWRIGHT (GB), won 5 races at 3 and 4 years, 2017 and £22,032 and placed once. 3rd Dam Someone Special, won 1 race at 3 years and placed 3 times including third in Coronation Stakes, Royal Ascot, Gr.2 and Venus Fillies Stakes, Kempton Park, L., from only 5 starts; dam of nine winners from 13 runners and 15 foals of racing age including- ONE SO WONDERFUL (GB), Champion older mare in Europe in 1998, won 5 races at 2 to 4 years including Juddmonte International Stakes, York, Gr.1, Equity Collections Sun Chariot Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2, Atalanta Stakes, Sandown Park, L. -

HORSE in TRAINING, Consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock N, Box 199

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock N, Box 199 Danehill (USA) Danetime (IRE) 308 (WITH VAT) Allegheny River (USA) Myboycharlie (IRE) MOONLIT SKY Rousillon (USA) Dulceata (IRE) (GB) Snowtop (2011) Seeking The Gold Mr Prospector (USA) A Bay Colt Calico Moon (USA) (USA) Con Game (USA) (2001) Strawberry Roan Sadler's Wells (USA) (IRE) Doff The Derby (USA) MOONLIT SKY (GB), placed twice at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 66 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 66 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 3 runs 2 pl £986 1st Dam CALICO MOON (USA), ran in France at 2 years; dam of two winners from 5 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SILK COTTON (USA) (2006 f. by Giant's Causeway (USA)), won 4 races at 4 and 5 years in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and £70,441 and placed 11 times. CRUACHAN (IRE) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), placed once at 3 years; also won 1 race over hurdles and placed 3 times. Moonlit Sky (GB) (2011 c. by Myboycharlie (IRE)), see above. She also has a 2013 filly by Sir Percy (GB). 2nd Dam STRAWBERRY ROAN (IRE) , won 3 races including Derrinstown Stud 1000 Guineas Trial, Leopardstown, L. and Eyrefield 2yo Stakes, Leopardstown, L. , second in Irish 1000 Guineas, Curragh, Gr.1 , third in Meld Stakes, Curragh, Gr.3 ; Own sister to IMAGINE (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 12 foals of racing age including- Berry Blaze (IRE) (f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years in South Africa and £35,633 and second in Korea Racing Authority Fillies Guineas, Greyville, Gr.2 , Gerald Rosenberg Stakes, Turffontein, Gr.2 , third in South African Fillies Classic, Turffontein, Gr.1 , Woolavington 2000, Greyville, Gr.1 and Gold Bracelet Stakes, Greyville, Gr.2 . -

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams Anabaa (USA) Danzig (USA) Sire: (Bay 1992) Balbonella (FR) STYLE VENDOME (FR) (Grey 2010) Place Vendome (FR) Dr Fong (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (Grey 2004) Mediaeval (FR) (Bay filly 2015) Green Desert (USA) Danzig (USA) Dam: (Bay 1983) Foreign Courier (USA) ALABASTRINE (GB) (Grey 2000) Alruccaba Crystal Palace (FR) (Brown/Grey 1983) Allara 3Sx3D Danzig (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (2015 filly by STYLE VENDOME (FR)), unraced in GB/IRE. 1st dam. ALABASTRINE (GB) (2000 mare by GREEN DESERT (USA)); in GB/IRE, placed once, £1,145 at 3 years, exported to France; dam of 11 known foals; 6 known runners; 4 known winners. HAIL CAESAR (IRE) (2006 gelding by MONTJEU (IRE)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £8,638 at 2 years, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £19,638 at 3 years; in Belgium, won 1 race, £1,293 at 5 years, won 2 races and placed twice, £4,084 at 6 years; in France, unplaced at 2 years, unplaced at 3 years, unplaced at 6 years, unplaced at 10 years; in GB/IRE over hurdles, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £11,137 at 4 years, placed once, £143 at 5 years; in GB/IRE over fences, placed once, £430 at 5 years, exported to Belgium. ALBASPINA (IRE) (2009 mare by SELKIRK (USA)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £2,264 at 2 years, placed twice, £1,819 at 3 years; dam of- Hiss Beau (QTR) (2014 filly by ROYAL APPLAUSE (GB)); in Qatar, unplaced at 3 years. -

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for WHOLE GRAIN (GB) - Three Dams

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for WHOLE GRAIN (GB) - Three Dams Danzig (USA) Northern Dancer Sire: (Bay 1977) Pas de Nom (USA) POLISH PRECEDENT (USA) (Bay 1986) Past Example (USA) Buckpasser WHOLE GRAIN (GB) (Chesnut 1976) Bold Example (USA) (Bay mare 2001) Mill Reef (USA) Never Bend Dam: (Bay 1968) Milan Mill MILL LINE (Bay 1985) Quay Line High Line (Bay 1976) Dark Finale WHOLE GRAIN (GB) (2001 mare by POLISH PRECEDENT (USA)); in GB/IRE, unplaced at 2 years, placed once, £434 at 3 years, unplaced at 4 years, unplaced at 5 years; in France, placed twice, £2,872 at 4 years; dam of 6 known foals; 1 known runner; 1 known winner. Tioman Two (GB) (2007 gelding by RED RANSOM (USA)), unraced in GB/IRE. LOUIS THE PIOUS (GB) (2008 gelding by HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR (IRE)); in GB/IRE, placed once, £265 at 2 years, won 4 races and placed 4 times, £29,057 at 3 years, placed 4 times, £29,946 at 4 years, won 1 race and placed once, £44,455 at 5 years, placed once, £9,625 at 6 years. (2009 mare by TEOFILO (IRE)). Oatmeal (GB) (2011 filly by DALAKHANI (IRE)), unraced in GB/IRE, exported to France. Swaheen (GB) (2012 colt by LAWMAN (FR)), unraced in GB/IRE. (2013 colt by SIR PERCY (GB)). No Return in 2010. 1st dam. MILL LINE (1985 mare by MILL REEF (USA)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race and placed 3 times, £3,473 at 3 years, WON Royal British Legion Stakes, Doncaster, 1988, SECOND Links Stakes, Redcar, 1988, exported to USA; dam of 13 known foals; 11 known runners; 9 known winners. -

HORSE in TRAINING, the Property of Juddmonte Farms

HORSE IN TRAINING, the Property of Juddmonte Farms Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock H, Box 126 Danzig (USA) Danehill (USA) 551 (WITH VAT) Razyana (USA) Cacique (IRE) Kahyasi PRESTO (GB) Hasili (IRE) Kerali (2015) Mr Prospector (USA) A Bay Gelding Distant View (USA) Allegro Viva (USA) Seven Springs (USA) (2002) Nijinsky (CAN) Musicanti (USA) Populi (USA) PRESTO (GB), unraced, own brother to CANTICUM (GB). 1st Dam ALLEGRO VIVA (USA), unraced; Own sister to DISTANT MUSIC (USA); dam of five winners from 5 runners and 7 foals of racing age viz- CANTICUM (GB) (2009 c. by Cacique (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years in France and £131,750 including Qatar Prix Chaudenay, Longchamp, Gr.2, placed 3 times including second in Prix de Lutece, Longchamp, Gr.3 and Prix Michel Houyvet, Deauville, L. UPHOLD (GB) (2007 g. by Oasis Dream (GB)), won 10 races at 3 to 6 years at home and in France and £89,239 and placed 22 times. BUSY STREET (GB) (2012 g. by Champs Elysees (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years and £13,003 and placed 11 times; also placed once in a N.H. Flat Race. FENGATE (GB) (2013 f. by Champs Elysees (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years in France and £21,443 and placed 6 times. ALLEGREZZA (GB) (2011 f. by Sir Percy (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years in France, £10,417. Presto (GB) (2015 g. by Cacique (IRE)), see above. She also has a 2017 colt by Kyllachy (GB). 2nd Dam MUSICANTI (USA), won 1 race in France and £19,669 and placed 4 times; dam of four winners from 9 runners and 11 foals of racing age viz- DISTANT MUSIC (USA) (c. -

Sue Johnson & John Bromfield Owner Profile

The SPRING 2013 KINGSCLERE Quarter THE PARK HOUSE STABLES NEWSLETTER The KINGSCLERE Quarter THE fter what has seemed like an eternity, the dark, cold and often wet days of the winter months are A finally subsiding and spring will be welcomed with open arms by all at Kingsclere when it eventually arrives! The combination of short days, bad weather and lack of racecourse activity make the off season a tough period for everyone working at Park House but the load has been made a little lighter this year with the exciting prospect of what appears to be a very strong team of horses for the coming flat season. It is always a benefit to any yard to have a strong team of older SIDE GLANCE braving the elements horses and some familiar faces as well as a couple of exciting new Front cover: Rob Hornby leading the string home, additions means we have strength in depth in this department. Summer 2012 Back cover: ‘I’m ready for the flat season – are you’? Side Glance has been a stable stalwart for the past three flat Flora and Will seasons and his achievements in 2012 were a testament to his consistency and versatility. As winner of the Group 3 Diomed Stakes at Epsom in June, he went on to be placed at Group 2 and Group CONTENTS 1 level most notably when he chased home the mighty Frankel, at a respectable distance, in the Queen Anne Stakes with only the top THE SEASON AHEAD 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8 class miler Excelebration in between! Side Glance now looks ready ANDREW BALDING for the step up to ten furlongs. -

The Royal Engineers Journal

THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL. Vol. III. No. 2. FEBRUARY, 1906. CONTENTS. 1. Royal Engineer Duties n the Future. PAGo. By Bt. Col. E. R. KENYON, R.E. 2. Organisatton of oyal Engineer 81 Capt. Units for Employment with C. DE W. CROOKSHANK, R.E. Cavalry. By (With Photo) ... 3. Entrenching under Fire. 84 By Bt. Lt.-Col. G. M. HEATH, D.s.o., Photos) ... ... ... ... R.E. (With 4. Some Notes on the Modern Coast Fortress. 91 By Col. T. RYDER MAIN, C.B., The MechanalC Conveyance R.E. 93 of Order. By Major L.J. DOPPING-HEPENsTAL 6 The Engineers of the German R E. Army. By Col. J. A. FERRIER, D.S.., R.E... 7. Transcripts:-Hutted 105 Hospitals in War. (With Plate) Some Work by the Electrical 124 Engineers, R.E. (V.) .. 8. Review:--The Battle ... 138 oe Wavre and Grouchy' Re treat. (Col. By W. Hyde Kelly, R.E. E. M. Lloyd, late R.E.) 9. Notices of Magazines .. 141 10. Correspondence:-The '43 Prevention of Dampness due to Condensation By Major in Magazines. T. E. NAIS, R.E. ... 11. Reeent PnbRcllinan ... 155 ....JV"O ... ... .. ... ... '57 INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY PRICE, DO NOT REMOVE SOME PUBLICATIONS BY THE ROYAL ENGINEERS INSTITUTE. NET PBICE TO NON- TITLE AND AUTHOR. MEMBERS. s. d. 1902 5 0 Edition ........... 3x.............. 5" B.E. Field Service pocket-Book. 2nd an Account of the Drainage and The Destruction of Mosquitos, being this object during 1902 and 1903 at other works carried out with 2 6 Hodder, R.E ...... ...............1904 St. Lucia, West Indies, by Major W. -

Carrier Pigeons (Portugal)

Version 1.0 | Last updated 12 February 2016 Carrier Pigeons (Portugal) By João Moreira Tavares Since ancient times, carrier pigeons have been used successfully in various armed conflicts. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, several European armies created a pigeon service. During World War I the losses of killed, wounded or missing carrier pigeons are estimated not to have exceeded 5 percent, which represents a success rate of 95 percent in delivering pigeon-grams, or messages carried by pigeons in the form of orders or sketches. Table of Contents 1 Development of the Portuguese Military Pigeon Service 2 Portugal’s use of Carrier Pigeons in World War I Notes Selected Bibliography Citation Development of the Portuguese Military Pigeon Service The importance of carrier pigeons was widely recognized in European armies, especially after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71. France rushed to create lofts in all strongholds across its eastern boundary. For its part, Germany was the first country to organize an army pigeon service while also enhancing the civilian service. However, it was Belgium - considered the home of pigeon-raising and where pigeon racing had become a national sport - that bred the best specimens of carrier pigeons and exported to other countries, including Portugal, where the first specimen arrived in August 1875. From 1881, the Portuguese military pigeon service began to take shape, though in a rather irregular manner at first. After 1888, according to a plan never fully achieved, lofts were built throughout the country, furnished with pigeons which came from Belgium and France in 1884, 1887 and 1901. -

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648

The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Worton, Jonathan Citation Worton, J. (2015). The royalist and parliamentarian war effort in Shropshire during the first and second English civil wars, 1642-1648. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Download date 24/09/2021 00:57:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/612966 The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Chester For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan Worton June 2015 ABSTRACT The Royalist and Parliamentarian War Effort in Shropshire During the First and Second English Civil Wars, 1642-1648 Jonathan Worton Addressing the military organisation of both Royalists and Parliamentarians, the subject of this thesis is an examination of war effort during the mid-seventeenth century English Civil Wars by taking the example of Shropshire. The county was contested during the First Civil War of 1642-6 and also saw armed conflict on a smaller scale during the Second Civil War of 1648. This detailed study provides a comprehensive bipartisan analysis of military endeavour, in terms of organisation and of the engagements fought. Drawing on numerous primary sources, it explores: leadership and administration; recruitment and the armed forces; military finance; supply and logistics; and the nature and conduct of the fighting. -

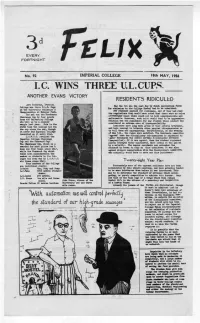

Felix Issue 085, 1956

3 EVERY FORTNIGHT No. 92 IMPERIAL COLLEGE 18th MAY, 1956 I.C. WINS THREE U.L.CUPS ANOTHER EVANS VICTORY RESIDENTS RIDICULED Last Saturday, Imperial College won three U.L.U. Cups May the 1st was the last day by whioh application forms at the University Athletics C for admission to the College Hostel had to be submitted. Championships at Hotspur Park. 250 students applied for residenoe, and if they had read the regulations they would have noted that there were no rules The men won the Roseberry ofbehaviour sinoe these could not be both oomprehensible and Challenge Cup by four points enforceable. Moreover, such rules would tend to be oppressive. from the University Collage Eviction was the punishment for any student whose conduct was who beat us by a similar considered an extreme oase of irresponsibility. margin last year. Ibis is the sixth time the college has won Residents have long been proud of this liberal treatment, the cup sinoe the war, though and have learned to tolerate other peoples idiosyncrasies or it never had Imperial College to tell them off appropiately. Unfortunately, on the evening inscribed on it until 1946. of May 1st., the ruLss were modified. The Residents committee I.C.W.S.C. retained the 'agreed' that the disciplinary sub-oommittee be empowered to Imperial College Challenge 'gate' Residents who oomrait certain disciplinary offences Cup and the Sherwood Cup. (unspecified). If it was agreed, then the student represent The Challenge'Cup, which is a ativea betrayed their electorate. More likely it was passed awarded for most points has b by a majority. -

'Choctaw: a Cultural Awakening' Book Launch Held Over 18 Years Old?

Durant Appreciation Cultural trash dinner for meetings in clean up James Frazier Amarillo and Albuquerque Page 5 Page 6 Page 20 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma May 2013 Issue Tribal Council meets in regular April session Choctaw Days The Choctaw Nation Tribal Council met in regular session on April 13 at Tvshka Homma. Council members voted to: • Approve Tribal Transporta- returning to tion Program Agreement with U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs • Approve application for Transitional Housing Assis- tance Smithsonian • Approve application for the By LISA REED Agenda Support for Expectant and Par- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma 10:30 a.m. enting Teens, Women, Fathers Princesses – The Lord’s Prayer in sign language and their Families Choctaw Days is returning to the Smithsonian’s Choctaw Social Dancing • Approve application for the National Museum of the American Indian in Flutist Presley Byington Washington, D.C., for its third straight year. The Historian Olin Williams – Stickball Social and Economic Develop- Dr. Ian Thompson – History of Choctaw Food ment Strategies Grant event, scheduled for June 21-22, will provide a 1 p.m. • Approve funds and budget Choctaw Nation cultural experience for thou- Princesses – Four Directions Ceremony for assets for Independence sands of visitors. Choctaw Social Dancing “We find Choctaw Days to be just as rewarding Flutist Presley Byington Grant Program (CAB2) Soloist Brad Joe • Approve business lease for us as the people who come to the museum say Storyteller Tim Tingle G09-1778 with Vangard Wire- it is for them,” said Chief Gregory E.