Motifs and Moral Ambiguity in Over the Garden Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic News

Dove 333 Central A GE P U. ATLANTICNEWS.COM VOL 34, NO 34 |AUGUST 22, 2008 | ATLANTIC NEWS | PAGE 1APresor . O. S. J. P AID FOSTER & CO ostal Customer r, POS NH 03820 INSIDE: ted Standard TA ve. TV LISTINGS GE , IN & C. BACK TO SCHOOL Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, AUGUST 22, 2008 Vol. 34 | No. 34 | 24 Pages Monarchs and milkweed Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Diligent monitoring helps conserve butterfly habitats BY LIZ PREMO ly looking for evidence of hart’s face. a measure of success in ticipant in the Minnesota- This is a busy time of ATlaNTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER a familiar seasonal visitor There’s a second one promoting the propagation based Monarch Larva year for monarchs and their ampton resident — the monarch butterfly. finding its way around on of Danaus plexippus, a cause Monitoring Project, Geb- offspring. Linda Gebhart “There’s one!” she another leaf of a nearby which Gebhart wholeheart- hart is joining other indi- “They are very active His on a mission exclaims, pointing to a very milkweed, and further edly supports. In fact, she viduals in locales across because there’s milkweed of royal proportions on a tiny caterpillar less than an investigation reveals a few has even gone so far as to the continent in “collect- in bloom,” Gebhart says, sunny August morning, eighth of an inch long. It’s tiny white eggs stuck to the apply for — and receive — ing data that will help to “so you have the adults just a few steps away from smaller than a grain of rice, undersides of other leaves, the special designation of a explain the distribution drinking the nectar, then her beach cottage. -

Tove Lo Queen of the Clouds Album Zip

Tove Lo Queen Of The Clouds Album Zip Tove Lo Queen Of The Clouds Album Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Tove Lo - Queen of the Clouds (Deluxe) Full Album Leak Free Download Link MP3 ZIP RAR Artist: Tove Lo Title: Queen of the Clouds (Deluxe). Free Download.. Find album release information for Queen of the Clouds - Tove Lo on AllMusic.. Download doc, mobi, txt or pdf. Download zip, rar. There Dickens was born in 1812. When tove lo queen of the clouds album zip epub was the Three Hundred.. Queen of the Clouds (Blueprint Edition) Tove Lo . She returned in 2016 with her second album, Lady Wood, which delivered more of her signature mix of cool.. 20 jan. 2015 . Format: lbum Completo e Faixa a Faixa tudo em M4A iTunes Plus e MP3 320 Kbps + tags corretas + capa do lbum inserida nas msicas.. Discover ideas about Tove Lo Album. Artist: Tove Lo / Album: Queen Of The Clouds (Deluxe Edition) / Year: 2014. Tove Lo AlbumHabits Stay HighHippie.. 'Tove lo queen of the clouds album download zip'. Play full-length songs from Queen Of The Clouds (Explicit) by Tove Lo on your phone, computer and . Album. Queen Of The Clouds. Tove Lo. Play on Napster.. Oct 2, 2015 . Title: Queen Of The Clouds (Blueprint Edition); Artist: Tove Lo; Genre: Pop, Alternative . Album Name, Length, Format, Sample Rate, Price.. Tracklist with lyrics of the album QUEEN OF THE CLOUDS [2014] from Tove Lo: The Sex [Intro] - My Gun - Like Em Young - Talking Body - Timebomb - The Love.. The Sex Intro test.ru lo queen of the clouds album. -

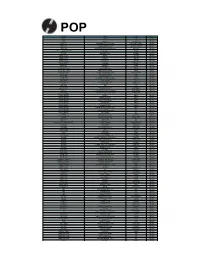

Order Form Full

POP ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADELE 19 (180 GR) CBS RM133.00 ADELE 21 CBS RM116.00 ADELE 25 (180 GR) XL RECORDINGS RM138.00 AMOS, TORI ABNORMALLY ATTRACTED TO SIN UNIVERSAL REPUBLIC RM151.00 AMOS, TORI LITTLE EARTHQUAKES (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UNDER THE PINK (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UPSIDE DOWN: FM RADIO BROADCASTS BAD JOKER RM122.00 BENNETT, TONY & LADY GAGA CHEEK TO CHEEK POLYDOR RM127.00 BEYONCE BEYONCE COLUMBIA RM178.00 BEYONCE LEMONADE (180 GR) COLUMBIA RM159.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN BELIEVE DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN JOURNALS DEF JAM RM140.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD 2.0 DEF JAM RM112.00 BILLIE JOE & NORAH FOREVERLY WARNER BROS RM124.00 BUGG, JAKE ON MY ONE ISLAND RM134.00 BUGG, JAKE SHANGRI-LA ISLAND RM134.00 CHARLI XCX SUCKER ATLANTIC RM117.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT FLYING HIGH (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT RIBBON OF GOLD (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT THE KIDS ARE THE SAME (180 GR) GET HIP/COLUMBIA RM110.00 COLLINS, PHIL ...BUT SERIOUSLY (180 GR) RHINO RM154.00 COLLINS, PHIL FACE VALUE (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 COLLINS, PHIL NO JACKET REQUIRED (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 CULTURE CLUB LIVE AT WEMBLEY - WORLD TOUR 2016 CLEOPATRA RM127.00 CYRUS, MILEY YOUNGER NOW RCA RM125.00 DARE, DOUGLAS AFORGER (CLEAR VINYL) ERASED TAPES RM142.00 DUFFY ROCKFERRY MERCURY RM112.00 EKKO, MIKKY TIME RCA RM103.00 FALL OUT BOY INFINITY ON HIGH (180 GR) ISLAND RM151.00 FURTADO, NELLY THE RIDE (180 GR) NELSTAR MUSIC RM134.00 GO-GO'S LET'S HAVE A PARTY: -

Taking in the Colors of Autumn DU Law Program Clinic to Put on Help Clear Probation Records

November 3, 2016 Volume 96 Number 12 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 Duquesne Taking in the colors of autumn DU law program clinic to put on help clear probation records Zachary Landau Carolyn Conte staff writer staff writer On Oct. 11, students in Duquesne’s Duquesne’s Juvenile Defender Physician Assistant Studies Pro- Clinic won a $100,000 grant to help gram learned that the school’s current or potential public housing standing with the Accreditation Re- residents with juvenile records to at- view Commission on Education for tain or keep their homes. the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA) The Department of Housing and might be in trouble. Urban Development and the U.S. In a meeting with students of Department of Justice awarded the Duquesne’s Physician Assistant money in September to Duquesne program, Department Chair and law professor Tiffany Sizemore- Professor Bridget Calhoun and Thompson’s Juvenile Defender Clin- Rangos School of Health Sciences ic. Ten law students from the clinic Interim Dean Paula Turocy ex- will visit Pittsburgh public housing plained that the ARC-PA has put sites in November to interview and the department on accreditation give legal advice to residents. probation for two years. To expunge — or remove — resi- Probation, as explained on the dents’ juvenile records, the clinic will ARC-PA’s website, is a temporary go through a multistep process with status for programs that either fail potential clients. First, the clinic must to meet the board’s standards or “the establish that the person qualifies for capability of the program to provide Jordan Miller/Staff Photographer the services and is “actually eligible to have their juvenile record expunged,” see PROBATION — page 2 A tree on Forbes Avenue sees its leaves begin to change colors. -

Order Form Full

POP ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADELE 19 (180 GR) CBS RM127.00 ADELE 21 CBS RM112.00 ADELE 25 (180 GR) XL RECORDINGS RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UNDER THE PINK (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM127.00 AMOS, TORI UPSIDE DOWN: FM RADIO BROADCASTS BAD JOKER RM117.00 BELL, DRAKE READY STEADY GO! SURFDOG RM109.00 BENNETT, TONY & LADY GAGA CHEEK TO CHEEK POLYDOR RM122.00 BEYONCE LEMONADE (180 GR) COLUMBIA RM152.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN BELIEVE DEF JAM RM108.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN JOURNALS DEF JAM RM135.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD DEF JAM RM108.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD 2.0 DEF JAM RM108.00 BILLIE JOE & NORAH FOREVERLY WARNER BROS RM119.00 BUGG, JAKE ON MY ONE ISLAND RM128.00 BUGG, JAKE SHANGRI-LA ISLAND RM128.00 CHARLI XCX SUCKER ATLANTIC RM113.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT FLYING HIGH (180 GR) GET HIP RM94.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT RIBBON OF GOLD (180 GR) GET HIP RM94.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT THE KIDS ARE THE SAME (180 GR) GET HIP/COLUMBIA RM106.00 COLLINS, PHIL ...BUT SERIOUSLY (180 GR) RHINO RM148.00 COLLINS, PHIL FACE VALUE (180 GR) RHINO RM119.00 COLLINS, PHIL NO JACKET REQUIRED (180 GR) RHINO RM119.00 CULTURE CLUB LIVE AT WEMBLEY - WORLD TOUR 2016 CLEOPATRA RM122.00 CYRUS, MILEY YOUNGER NOW RCA RM120.00 DARE, DOUGLAS AFORGER (CLEAR VINYL) ERASED TAPES RM137.00 DUFFY ROCKFERRY MERCURY RM108.00 EILISH, BILLIE DON'T SMILE AT ME (COLOR) INTERSCOPE RM114.00 EKKO, MIKKY TIME RCA RM100.00 EURYTHMICS GREATEST HITS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM172.00 FALL OUT BOY INFINITY ON HIGH (180 GR) ISLAND RM145.00 FURTADO, NELLY THE RIDE (180 GR) NELSTAR MUSIC RM128.00 GO-GO'S LET'S HAVE A PARTY: -

El Modelo De Cuento De Hadas De Las Producciones Animadas De Walt Disney

178 El modelo de cuento de hadas de las producciones animadas de Walt Disney EL MODELO DE CUENTO DE HADAS DE LAS PRODUCCIONES ANIMADAS DE WALT DISNEY: LA IMPORTANCIA DE LA MÚSICA EN SU CONSTRUCCIÓN Y SU INFLUENCIA EN PELÍCULAS PRODUCIDAS POR OTROS ESTUDIOS Alba Montoya Rubio Universitat de Barcelona Cuando nos referimos a los clásicos Disney es When referring to “classic Disney”, it is usual to muy común asociarlos con los cuentos de ha- associate these movies with fairy tales and songs. das y la presencia de canciones. Sin embargo, Nevertheless, not all Disney productions are fairy no todas las producciones de Disney son adap- tales adaptations, but the studio takes elements taciones de cuentos, pero el estudio de anima- from these tales and puts them in many of its ción toma elementos de este tipo de relatos y movies. In this way, as well as with the help of los traslada a muchas de sus películas. De esta songs, Disney creates its own conventions and a manera, y con la ayuda de las canciones, Disney new model of fairy tale. Moreover, throughout crea un modelo propio de cuentos de hadas. their history, the Disney company have incor- Además, en su historia, la compañía Disney porated their own conventions, as giving more ha incorporado convenciones propias, como importance to romance plots or the inclusion of dar más importancia a las tramas románticas o the American Dream. Thus, the main point of la inclusión del tema del sueño americano. La this paper is clarifying how these conventions are cuestión que se plantea este artículo es diluci- influent, both in animated films and live-action dar hasta qué punto dichas convenciones son film adaptations of fairy tales. -

Best of 2014 Listener Poll Nominees

Nominees For 2014’s Best Albums From NPR Music’s All Songs Considered Artist Album ¡Aparato! ¡Aparato! The 2 Bears The Night is Young 50 Cent Animal Ambition A Sunny Day in Glasgow Sea When Absent A Winged Victory For The Sullen ATOMOS Ab-Soul These Days... Abdulla Rashim Unanimity Actress Ghettoville Adia Victoria Stuck in the South Adult Jazz Gist Is Afghan Whigs Do To The Beast Afternoons Say Yes Against Me! Transgender Dysphoria Blues Agalloch The Serpent & The Sphere Ages and Ages Divisionary Ai Aso Lone Alcest Shelter Alejandra Ribera La Boca Alice Boman EP II Allah-Las Worship The Sun Alt-J This is All Yours Alvvays Alvvays Amason Duvan EP Amen Dunes Love Ana Tijoux Vengo Andrew Bird Things Are Really Great Here, Sort Of... Andrew Jackson Jihad Christmas Island Andy Stott Faith In Strangers Angaleena Presley American Middle Class Angel Olsen Burn Your Fire For No Witness Animal Magic Tricks Sex Acts Annie Lennox Nostalgia Anonymous 4 David Lang: love fail Anthony D'Amato The Shipwreck From The Shore Antlers, The Familiars The Apache Relay The Apache Relay Aphex Twin Syro Arca Xen Archie Bronson Outfit Wild Crush Architecture In Helsinki NOW + 4EVA Ariel Pink Pom Pom Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro Latin Orchestra The Offense of the Drum Ásgeir In The Silence Ashanti BraveHeart August Alsina Testimony Augustin Hadelich Sibelius, Adès: Violin Concertos The Autumn Defense Fifth Avey Tare Enter The Slasher House Azealia Banks Broke With Expensive Taste Band Of Skulls Himalayan Banks Goddess Barbra Streisand Partners Basement Jaxx Junto Battle Trance Palace Of Wind Beach Slang Cheap Thrills on a Dead End Street Bebel Gilberto Tudo Beck Morning Phase Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Bellows Blue Breath Ben Frost A U R O R A Benjamin Booker Benjamin Booker Big K.R.I.T. -

Dapper 4.X Manual Apple Music to Digital Audio Player Sync Tool

Dapper 4.x Manual Apple Music to Digital Audio Player Sync Tool Updated: December, 2019 DAPPER OSX MANUAL 1 Whats new and changed recently: Version 4.54: Fixed a crash bug where Dapper would incorrectly sync playlists and files sometimes if the Artist, Album or Track names ended in a space. Version 4.53: Fixed a crash bug that would crash Dapper when Batched mode was turned on in some cases. Added a feature to auto-select android based DAP drives if we recognize them. Version 4.52: Added even better progress tracking in batched Android mode. Fixed a bug where some album art would not copy over correctly. Fixed a crash bug that would crash Dapper when Batched mode was turned on in some cases. Version 4.51: Added automatic Batched mode for Android (MTP) devices. If more than 4GB of data is to be copied, Dapper will automatically suggest using Batched mode since it is almost double the speed. A checkbox on the confirmation page allows you to revert. Added much better “Cancel” functionality for Android players as well as vastly improved progress tracking. Version 4.50: Embedded the Android File Transfer capabilities directly into the Dapper app, so that you no longer need to download Dapper Scripts for Android based DAPs. This also means that Dapper does a much better job of detecting Android players. Added a warning to users noting that larger (1TB/2TB or more) libraries should stick to “Audiophile mode” and not direct music access because MacOS Music is very slow in these cases. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

1/1/2016 — 2/29/2016 In January and February 2016, RIAA certified158 Digital Single Awards and 74 Album Awards. Complete lists of all RIAA Gold & Platinum Awards dating all the way back to 1958 are available at the newly redesigned riaa.com. RIAA GOLD & JAN. & FEB. 2016 PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (46) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 2/8/2016 AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF CAPITOL RECORDS 2 7/1/2014 SUMMER 1/25/2016 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 6 10/23/2015 1/25/2016 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 5 10/23/2015 1/7/2016 HERE ALESSIA CARA DEF JAM 2 5/1/2015 1/26/2016 LOVE ME HARDER ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 3 8/25/2014 1/26/2016 LOVE ME HARDER ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 2 8/25/2014 1/26/2016 HOTLINE BLING DRAKE YOUNG MONEY/CASH 5 7/31/2015 MONEY/REPUBLIC RECORDS 2/29/2016 THINKING OUT LOUD ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC RECORDS 6 9/24/2014 2/29/2016 PHOTOGRAPH ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC RECORDS 2 5/11/2015 1/28/2016 STAY FLORIDA GEORGIA BMX 2 12/4/2012 LINE 1/29/2016 BURNIN’ IT DOWN JASON ALDEAN BROKEN BOW 2 7/22/2014 2/1/2016 SHE’S COUNTRY JASON ALDEAN BROKEN BOW 3 12/1/2008 2/15/2016 BIRTHDAY SEX JEREMIH DEF JAM 2 6/30/2009 1/15/2016 WHAT DO YOU MEAN JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM RECORDS 3 8/28/2015 1/15/2016 WHAT DO YOU MEAN JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM RECORDS 4 8/28/2015 1/15/2016 SORRY JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM 3 10/28/2015 1/15/2016 LOVE YOURSELF JUSTIN BIEBER DEF JAM 2 11/13/2015 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards JAN. -

Fairy Tale Films

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2010 Fairy Tale Films Pauline Greenhill Sidney Eve Matrix Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Greenhill, P., & Matrix, S. E. (2010). Fairy tale films: Visions of ambiguity. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fairy Tale Films Visions of Ambiguity Fairy Tale Films Visions of Ambiguity Pauline Greenhill and Sidney Eve Matrix Editors Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 2010 Copyright © 2010 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Cover photo adapted from The Juniper Tree, courtesy of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, Nietzchka Keene papers, 1979-2003, M2005-051. Courtesy of Patrick Moyroud and Versatile Media. ISBN: 978-0-87421-781-0 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-782-7 (e-book) Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free, recycled paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fairy tale films : visions of ambiguity / Pauline Greenhill and Sidney Eve Matrix, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-87421-781-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-87421-782-7 (e-book) 1. Fairy tales in motion pictures. 2. Fairy tales--Film adaptations. I. Greenhill, Pauline. -

Tove Lo Lady Wood Album Download Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Leaked Full Album Zip

tove lo lady wood album download Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Leaked Full Album Zip. 1.Fairy Dust 2. Influence (feat. Wiz Khalifa) 3. Lady Wood 4. True Disaster 5. Cool Girl 6. Vibes (feat. Joe Janiak) 7. Fire Fade (Chapter II) 8. Don’t Talk About It 9. Imaginary Friend 10. Keep it Simple 11. Flashes 12. WTF Is Love. ALBUM TAGS Tove Lo Lady Wood Complete Album Tove Lo Lady Wood Complete Album Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Complete Album leak Tove Lo Lady Wood download Tove Lo Lady Wood Complete Album Mp3 Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Mp3 Complete Album Tove Lo Lady Wood Full Album Download Tove Lo Lady Wood album download Downlooad Tove Lo Lady Wood Tove Lo Lady Wood album Tove Lo Lady Wood leak Tove Lo Lady Wood download album Download album Tove Lo Lady Wood Tove Lo Lady Wood download 2016 Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Album Tove Lo Lady Wood Download Free Tove Lo Lady Wood telecharger Tove Lo Lady Wood Download Full Album Tove Lo Lady Wood Download Full Album Free Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Tove Lo Lady Wood MP3 Track Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Full Song Tove Lo Lady Wood Download MP3 Tove Lo Lady Wood Download Song Tove Lo Lady Wood Song Tove Lo Lady Wood Track Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Song Download Tove Lo Lady Wood Song free. Tove Lo - Lady Wood album flac. Lady Wood is the second studio album by Swedish singer Tove Lo. It was released on 28 October 2016 by Island Records. -

Semantic Assets: Latent Structures for Knowledge Management

From the Institute of Information Systems of the University of Lubeck¨ Director: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. habil. Ralf M¨oller Semantic Assets: Latent Structures for Knowledge Management Dissertation for Fulfillment of Requirements for the Doctoral Degree of the University of Lubeck¨ from the Department of Computer Sciences Submitted by Sylvia Melzer from Hamburg Lubeck,¨ 2018 ii First referee: Prof. Dr. Ralf M¨oller Second referee: Prof. Dr. Christian Willi Scheiner Date of oral examination: June 21, 2018 Approved for printing. Lubeck,¨ August 15, 2018 Abstract In standard information retrieval systems, queries can be specified with differ- ent languages (string patterns, logical formulas, and so on). It is well known that it is hard to simultaneously maximize quality measures for query answers, such as, e.g., precision and recall. Retrieval of documents with high recall, while maintaining at least a decent precision level, is a frequent problem in knowledge management (KM) contexts based on information retrieval (IR) processes, e.g., for information association in business contexts. Similar to making implicit knowledge explicit, deriving explicit symbolic content descriptions is important in KM tasks. In this thesis we show how explicit symbolic descriptions can be combined with implicit holistic content representations known from information retrieval in order to support knowledge management processes in general, and informa- tion association based on IR query answering in particular. The methodology exhibited in this thesis is verified using representative examples, and validated with feasibility and effectiveness studies. iii iv Zusammenfassung In Standard-Information-Retrieval-Systemen k¨onnen Anfragen mit verschiede- nen Sprachen (Strings, logische Formeln usw. ) gestellt werden.