An Onomastic Analysis of 'Over the Garden Wall'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riverside Quarterly V2N4 Sapiro 1967-03

Riverside XZ ‘ RIVERS lue. QUARTERLY March 1967 Vol. u, 4 Editor: Leland Sapiro Associate Editor: Jim Harmon Poetry Editor: Jim Sallis Assistant Editors: Redd Boggs Edward Teach Jon White Send business correspondence and prose manuscripts to: This issue is dedicated to John W. Campbell, Jr., who is Box 82 University Station, Saskatoon, Canada the main subject in two articles. If Orlin Tremaine changed science fiction "from a didactic exercise into a form of art," Send poetry to: R.D. 3, Iowa City, Iowa 52240 then Campbell changed it from romance to novel, i.e., into an art form with social content. I do not prefer the type of story emphasised by Mr. Campbell's present magazine, but this in no way reduces indebtedness to him for any science fiction reader. table of contents "NOW HEAR THIS'." Everyone is urged to register at once for the 1967 science RQ Miscellany .................... 231 fiction convention to be held in New York city, September 1—4. Superman and the System ..... A S3 registration fee paid now entitles you to the usual con (first of two parts) ........... W.H.G. Armytage .... 232 vention privileges (e.g., reduced room rates) plus progress reports and a program book mailed in advance. Send cash or in Consubstantial ............ ....... Padraig 0 Broin .... 243 quiries to Nycon 3, Box 367, Gracie Square Sta., New York 10028. Creide's Lament for Cael ............ 244 Parapsychology: Fact or Fraud? .... Raymond Birge ..... 247 "RADIOHERO" The Bombardier .................... Thomas Disch ....... 265 Old Time Radio fans can anticipate Jim Harmon's book, The Great Radio Heroes, scheduled for publication by Doubleday On Being Forbidden Entrance to a Castle ... -

Bryan Curtis

The Library of America • Story of the Week Reprinted from Football: Great Writing about the National Sport (The Library of America, 2014), pages 413–34. Headnote by John Schulian. Originally appeared in Texas Monthly (January 2013). Copyright © 2013. Reprinted by permission of Texas Monthly. Bryan Curtis Bryan Curtis (b. 1977) is predictable only in that there seem to be surprises in everything he writes, good surprises, the kind that let readers know they can count on him for a unique take no matter what the subject. Consider the surge in concern over concussions in football from the NFL on down to the youth leagues. It was the youth leagues that fascinated Curtis, a staff writer at the website Grantland and a native Texan whose byline appears fre- quently in Texas Monthly. He wanted to see “how they were processing the news about football. How they were coming to grips with it. How they were, in some cases, ignoring it.” Curtis found the perfect team to study in Allen, Texas, outside Dallas—undefeated for years, loaded with prize elementary school athletes who would realize only later that they were saying good-bye to childhood. His story about them, “Friday Night Tykes,” appeared in Texas Monthly’s January 2013 issue and provided further evidence that he is one of the new century’s very best sportswriters. Curtis began his journalism career by writing about the real world for the New Republic and Slate, first explored the world of fun and games at the New York Times’ sports magazine Play, and returned to the serious side to help Tina Brown, the mercurial former Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor, launch The Daily Beast. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

Report on S-4 Starts Storm of Protests Saves Woman

’.^“.•'V'^ •*4n '-p £ ' HM'"*" _ C,--V ■, , ’ ',V >X5',V' PBBSH BUX fSieiihst hr V. 8. <WejaSer Bhrem, AVBRAGB DAltiY CIHCVLATIOX Mew Have* ; for the month of January, 1€ J8 'Increasing cloudineea and warm* er, followed by rain late ton i^ t 5 , 0 8 7 and Tlinradaf; ^ ateMher -of tke Aadlt Baroaa of !t.-« ' CIrcalatlooa State Library •'^- (FOUiSiM«-. -1 AGES) PRICE THREE CENTS MANCHEStER; CONN., WEDNESDAY,- FEBRUARY 22, 1928. VO L. XUl„ NO. 122. Classified Advertising on Page 12. CATFISH GROWS IN REPORT ON S-4 COAST BEAN PATCH. West Palm Beach, Fla., Feb. 22.— Farmer Jake Gray swears STARTS STORM to this fish story from the Everglades. He was plowing his Bean patch, he says, when he turned OF PROTESTS up a live catfish. If true, there is no telling what might have happened if the fish had remained in the Multi-Millionaire Oil M apaU Congressmen, Admirals and soil and become crossed with a snap Bean. The glades might With H. Mason Day and have reproduced a stew that Treasury Officials Indig would Be the envy of the now infamous army “ slumgullion.’ Celebrates The Day William J. Bnms Heat nant Over Results of Conrt’s Verdict on Con Alexandria, Va FeB, 22— Liter-<s»Alexandria had a Birthday fete for Naval ProBe. ^Washington which he attended per ally buried beneath flags and bunt SAVES WOMAN sonally. The 'date, however, was tempt Charges— Day Gets ing, .and inordinately proud of Its FeBruary 11, that Being the date Washington, FeB. 22.— Stormr. or distinction, this plaOT -Jittle .^Afir. upon which he actually was Born, Fonr Months and Noted protest ana indignation gathered FROMSHARKS ginla town led the uhtiq^. -

Demonizing Unions: Religious Rhetoric in the Early 20Th

DEMONIZING UNIONS: RELIGIOUS RHETORIC IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN STRIKE NOVEL A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by David Michael Cosca August 2019 © David Michael Cosca DEMONIZING UNIONS: RELIGIOUS RHETORIC IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN STRIKE NOVEL David Michael Cosca, Ph. D. Cornell University 2019 Demonizing Unions uncovers the significance of a Biblical idiom in American novels portraying violent labor conflicts from the 1910s to the 1930s. I reveal the different ways that Upton Sinclair’s King Coal and The Coal War, Mary Heaton Vorse’s Strike!, and Ruth McKenney’s Industrial Valley employ a Biblical motif both to emphasize the God-like power of Capital over society, and to critique an emergent socio-political faith in business power. The texts I examine demonstrate how it was clear to industrialists in the early 20th century that physical violence was losing its efficacy. Therefore, much of the brunt of the physical conflict in labor struggles could be eased by waging a war of ideas to turn public opinion into an additional, ultimately more powerful, weapon against the potential of organized labor. I argue that in these texts, the besmearing of the discontented workers as violent dupes of “outside agitators,” rather than regular folks with economic grievances, takes on Biblical proportions. In turn, these authors utilize Biblical stories oriented around conceptions of power and hierarchy to illuminate the potential of ordinary humans to effect their own liberation. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH David Cosca grew up in Santa Maria, CA. -

Tove Lo Queen of the Clouds Album Zip

Tove Lo Queen Of The Clouds Album Zip Tove Lo Queen Of The Clouds Album Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Tove Lo - Queen of the Clouds (Deluxe) Full Album Leak Free Download Link MP3 ZIP RAR Artist: Tove Lo Title: Queen of the Clouds (Deluxe). Free Download.. Find album release information for Queen of the Clouds - Tove Lo on AllMusic.. Download doc, mobi, txt or pdf. Download zip, rar. There Dickens was born in 1812. When tove lo queen of the clouds album zip epub was the Three Hundred.. Queen of the Clouds (Blueprint Edition) Tove Lo . She returned in 2016 with her second album, Lady Wood, which delivered more of her signature mix of cool.. 20 jan. 2015 . Format: lbum Completo e Faixa a Faixa tudo em M4A iTunes Plus e MP3 320 Kbps + tags corretas + capa do lbum inserida nas msicas.. Discover ideas about Tove Lo Album. Artist: Tove Lo / Album: Queen Of The Clouds (Deluxe Edition) / Year: 2014. Tove Lo AlbumHabits Stay HighHippie.. 'Tove lo queen of the clouds album download zip'. Play full-length songs from Queen Of The Clouds (Explicit) by Tove Lo on your phone, computer and . Album. Queen Of The Clouds. Tove Lo. Play on Napster.. Oct 2, 2015 . Title: Queen Of The Clouds (Blueprint Edition); Artist: Tove Lo; Genre: Pop, Alternative . Album Name, Length, Format, Sample Rate, Price.. Tracklist with lyrics of the album QUEEN OF THE CLOUDS [2014] from Tove Lo: The Sex [Intro] - My Gun - Like Em Young - Talking Body - Timebomb - The Love.. The Sex Intro test.ru lo queen of the clouds album. -

City of Santa Clara Recreation Activities Guide

Summer 2013 City of Santa Clara Recreation Activities Guide Our format has changed. Please see page 4 for detailed instructions on how to read the new class charts. City Web Address: www.santaclaraca.gov PARKS & RECREATION DEPARTMENT City Hall 1500 Warburton Ave. Santa Clara, CA 95050 Telephone: (408) 615-2260 www.santaclaraca.gov Class & Activity Information: (408) 615-3140 Programs are co-sponsored by Santa Clara Unified School District COMMUNITY RECREATION CENTER (CRC) Located in Central Park, 969 Kiely Blvd. Office hours: Monday through Thursday, 8:00 am-8:00 pm Friday, 8:00 am-5:00 pm Saturday, 9:00 am-12:00 pm INSIDE THIS ISSUE Closed on Sunday 41 Developmental Assets ................................................... 44 Infant & Tot Classes Santa Clara City residents or resident groups Class Locations .................................................................... 4 Adventures in Learning for Preschool-Aged Children ......... 10 may reserve Santa Clara park buildings Co-Sponsored Clubs........................................................... 43 Creative Arts ..................................................................10-11 Friends of Santa Clara Parks & Recreation......................... 42 Dance ................................................................................. 11 and picnic facilities at Central Park on a General Information .............................................................. 4 Music .............................................................................11-12 space available basis -

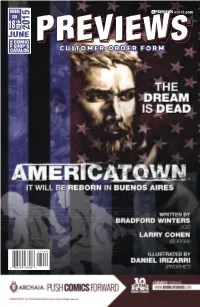

Customer Order Form June

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JUNE 2015 JUNE COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jun15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/7/2015 3:00:50 PM June15 C2 Future Dude.indd 1 5/6/2015 11:24:23 AM KING TIGER #1 HE-MAN AND THE DARK HORSE COMICS MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE MINI-COMIC COLLECTION HC DARK HORSE COMICS JUSTICE LEAGUE: GODS AND MONSTERS #1 DC COMICS GET JIRO: BLOOD AND SUSHI THE X-FILES: DC COMICS/VERTIGO SEASON 11 #1 IDW PUBLISHING DARK CORRIDOR #1 IMAGE COMICS PHONOGRAM: THE IMMATERIAL ANT-MAN: GIRL #1 LAST DAYS #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS Jun15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/6/2015 4:38:32 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius: The Second Journey Volume 1 TP/HC l AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT War Stories Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC War Stories Volume 2 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Over The Garden Wall #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Red Sonja/Conan #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Space Dumplins GN/HC l GRAPHIX Stringers #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Little Nemo: Big New Dreams HC l TOON GRAPHICS Kill La Kill Volume 1 GN l UDON ENTERTAINMENT CORP Book of Death: Fall of Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Ultraman Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS The Doctors Are In: The Essential and Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who l DOCTOR WHO Star Wars: The Original Topps Trading Card Series Volume 1 HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES The Walking Dead Figurine Magazine l EAGLEMOSS DC Masterpiece Figurine Collection #2: Femme Fatales Set l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #6 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man -

Trabajo Fin De Grado

Trabajo Fin de Grado Las series de animación dirigidas a la infancia y las representaciones del sexo y el género. Una aproximación desde el Trabajo Social. The animation shows aimed to the childhood and the sex and gender representations. An approach from Social Work. Autor/es Andrea Cebollada Latorre Director/es Antonio Eito Mateo FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y DEL TRABAJO 2017 Repositorio de la Universidad de Zaragoza – Zaguan http://zaguan.unizar.es Infinitas gracias al incesante apoyo de mi tutor Antonio Eito, mis compañeros del grado y mi familia durante este recorrido. ÍNDICE RESUMEN .......................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ......................................................................................................... 2 2. OBJETIVOS ................................................................................................................. 4 3. METODOLOGÍA .......................................................................................................... 5 3.1 UNA INVESTIGACIÓN CUALITATIVA DE MATERIALES VISUALES ............................ 5 3.2 TÉCNICAS E INSTRUMENTOS PARA LA OBTENCIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN ................ 6 3.3 TÉCNICAS DE ANÁLISIS DE DATOS .......................................................................... 7 4. DOCUMENTACIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA........................................................................... 8 4.1 INTRODUCCIÓN ..................................................................................................... -

Order Form Full

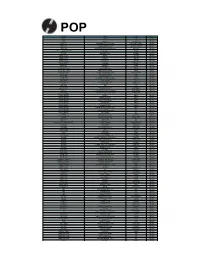

POP ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADELE 19 (180 GR) CBS RM133.00 ADELE 21 CBS RM116.00 ADELE 25 (180 GR) XL RECORDINGS RM138.00 AMOS, TORI ABNORMALLY ATTRACTED TO SIN UNIVERSAL REPUBLIC RM151.00 AMOS, TORI LITTLE EARTHQUAKES (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UNDER THE PINK (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UPSIDE DOWN: FM RADIO BROADCASTS BAD JOKER RM122.00 BENNETT, TONY & LADY GAGA CHEEK TO CHEEK POLYDOR RM127.00 BEYONCE BEYONCE COLUMBIA RM178.00 BEYONCE LEMONADE (180 GR) COLUMBIA RM159.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN BELIEVE DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN JOURNALS DEF JAM RM140.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD 2.0 DEF JAM RM112.00 BILLIE JOE & NORAH FOREVERLY WARNER BROS RM124.00 BUGG, JAKE ON MY ONE ISLAND RM134.00 BUGG, JAKE SHANGRI-LA ISLAND RM134.00 CHARLI XCX SUCKER ATLANTIC RM117.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT FLYING HIGH (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT RIBBON OF GOLD (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT THE KIDS ARE THE SAME (180 GR) GET HIP/COLUMBIA RM110.00 COLLINS, PHIL ...BUT SERIOUSLY (180 GR) RHINO RM154.00 COLLINS, PHIL FACE VALUE (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 COLLINS, PHIL NO JACKET REQUIRED (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 CULTURE CLUB LIVE AT WEMBLEY - WORLD TOUR 2016 CLEOPATRA RM127.00 CYRUS, MILEY YOUNGER NOW RCA RM125.00 DARE, DOUGLAS AFORGER (CLEAR VINYL) ERASED TAPES RM142.00 DUFFY ROCKFERRY MERCURY RM112.00 EKKO, MIKKY TIME RCA RM103.00 FALL OUT BOY INFINITY ON HIGH (180 GR) ISLAND RM151.00 FURTADO, NELLY THE RIDE (180 GR) NELSTAR MUSIC RM134.00 GO-GO'S LET'S HAVE A PARTY: -

Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Theses School of Film, Media & Theatre Summer 7-31-2018 Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation Wolfgang Boehm Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_theses Recommended Citation Boehm, Wolfgang, "Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animating Social Pathology: Ontology, Aesthetics, and Cartoon Alienation by Wolfgang Boehm Under the Direction of Professor Greg Smith ABSTRACT This thesis grounds an unstable ontology in animation’s industrial history and its plas- matic aesthetics, in-so-doing I find animation to be a site of rendering visible a particular con- frontation with an inability to properly rationalize, ossify, or otherwise delimit traditionally held boundaries of motility. Because of this inability, animation is privileged as a form to rethink our interactions with media technology, leading to utopian thought and bizarre, pathological behav- ior. I follow the ontological trend through animation studies, using Pixar’s WALL-E as a guide. I explore animation as an afterimage of social pathology, which stands in contrast to the more lu- dic thought of a figure such as Sergei Eisenstein, using Black Mirror’s “The Waldo Moment.” I look to two Cartoon Network shows as examples of potential alternatives to both the utopian and pathological of the preceding chapters. -

Taking in the Colors of Autumn DU Law Program Clinic to Put on Help Clear Probation Records

November 3, 2016 Volume 96 Number 12 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 Duquesne Taking in the colors of autumn DU law program clinic to put on help clear probation records Zachary Landau Carolyn Conte staff writer staff writer On Oct. 11, students in Duquesne’s Duquesne’s Juvenile Defender Physician Assistant Studies Pro- Clinic won a $100,000 grant to help gram learned that the school’s current or potential public housing standing with the Accreditation Re- residents with juvenile records to at- view Commission on Education for tain or keep their homes. the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA) The Department of Housing and might be in trouble. Urban Development and the U.S. In a meeting with students of Department of Justice awarded the Duquesne’s Physician Assistant money in September to Duquesne program, Department Chair and law professor Tiffany Sizemore- Professor Bridget Calhoun and Thompson’s Juvenile Defender Clin- Rangos School of Health Sciences ic. Ten law students from the clinic Interim Dean Paula Turocy ex- will visit Pittsburgh public housing plained that the ARC-PA has put sites in November to interview and the department on accreditation give legal advice to residents. probation for two years. To expunge — or remove — resi- Probation, as explained on the dents’ juvenile records, the clinic will ARC-PA’s website, is a temporary go through a multistep process with status for programs that either fail potential clients. First, the clinic must to meet the board’s standards or “the establish that the person qualifies for capability of the program to provide Jordan Miller/Staff Photographer the services and is “actually eligible to have their juvenile record expunged,” see PROBATION — page 2 A tree on Forbes Avenue sees its leaves begin to change colors.