Sp.Foster,Pandemonium and Parade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits: an Encyclopedia of Mononoke and Magic (Yokai Series Book 2) (English Edition) Online

ktapo [Free and download] The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits: An Encyclopedia of Mononoke and Magic (Yokai Series Book 2) (English Edition) Online [ktapo.ebook] The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits: An Encyclopedia of Mononoke and Magic (Yokai Series Book 2) (English Edition) Pdf Free Par Matthew Meyer DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #230483 dans eBooksPublié le: 2015-06-01Sorti le: 2015-06- 01Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 28.Mb Par Matthew Meyer : The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits: An Encyclopedia of Mononoke and Magic (Yokai Series Book 2) (English Edition) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits: An Encyclopedia of Mononoke and Magic (Yokai Series Book 2) (English Edition): Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Really coolPar StefI really loved this book ! It was very informative and full of a lot of surprise ! I recommand it highly. Présentation de l'éditeurIn Japan, it is said that there are 8 million kami. These spirits encompass every kind of supernatural creature; from malign to monstrous, demonic to divine, and everything in between. Most of them seem strange and scary—even evil—from a human perspective. They are known by myriad names: bakemono, chimimoryo, mamono, mononoke, obake, oni, and yokai. Yokai live in a world that parallels our own. Their lives resemble ours in many ways. They have societies and rivalries. -

A.C. Ohmoto-Frederick Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts GLIMPSING LIMINALITY AND THE POETICS OF FAITH: ETHICS AND THE FANTASTIC SPIRIT A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick © 2009 Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 v The dissertation of Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick was reviewed and approved* by the following: Thomas O. Beebee Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Japanese Véronique M. Fóti Professor of Philosophy Monique Yaari Associate Professor of French Caroline D. Eckhardt Professor of Comparative Literature and English Head of the Department of Comparative Literature *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii Abstract This study expands the concept of reframing memory through reconciliation and revision by tracing the genealogy of a liminal supernatural entity (what I term the fantastic spirit and hereafter denote as FS) through works including Ovid’s Narcissus and Echo (AD 8), Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova (1292-1300), Yokomitsu Riichi’s Haru wa Basha ni notte (1915), Miyazawa Kenji’s Ginga tetsudo no yoru (1934), and James Joyce’s The Dead (1914). This comparative analysis differentiates, synthesizes, and advances upon conventional conceptions of the fantastic spirit narrative. What emerges is an understanding of how fantastic spirit narratives have developed and how their changes reflect conceptions of identity, alterity, and spirituality. Whether the afterlife is imagined as spatial relocation, transformation of consciousness, transformation of body, or hallucination, the role of the fantastic spirit is delineated by the degree to which it elicits a more profound relationship between the Self and Other. -

Translation As 'Bakemono'

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 3, No. 3, September 2017 Translation as ‘Bakemono’: Shapeshifters of the Meiji Era (1868-1912) Daniel J. Wyatt and is left standing dumbfounded in a cemetery on the Abstract—Bakemono ( 化け物) or obake ( お化け) are outskirts of town as the woman transforms into a fox and runs Japanese terms for a class of yōkai: preternatural creatures of off (Takeishi 2016, 136-44) [1]. indigenous folklore. In English they might be referred to as The form of the fox taken by the woman, and the form that apparitions, phantoms, goblins, monsters, or ghosts. In the bakemono assume when they are exposed is referred to as literal sense, bakemono are things that change, referring to a their ‘shōtai’ (正体) or ‘true form’; however, the true form of state of transformation or shapeshifting. Japan’s period of ‘bunmei kaika’ (civilization and enlightenment) in the Meiji era the bakemono is not always known. Another example from (1868-1912) signifies the stigmatization of supernatural the Konjaku monogatari-shū tells of an unknown assailant shapeshifters and concurrent burgeoning of bakemono of a that frequents the Jijūden Palace (仁寿殿) every night: “a literal kind: translation. Following the Meiji Restoration of certain mono (lit. ‘thing’) comes at midnight to steal oil from 1868, translation of foreign literature became tantamount to the dissemination of modern thought and propelling the new the (palace) lamps” (shinya nakagoro nani mono ka ga governments’ efforts towards the creation of a modern state. yattekite, ōmiakashi wo nusumidashite; 真夜なかごろ何もの Meiji translated literature reveals the various cultural systems かがやってきて、 御燈油をぬすみだして) (Takeishi 2016, 41) through which new knowledge was processed and transitioned during this period, resulting in translations which—like the [2]. -

Pandemonium and Parade

Pandemonium and Parade Pandemonium and Parade Japanese Monsters and the Culture of YOkai Michael Dylan Foster UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley . Los Angeles . London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. Frontispiece and title-page art: Details from Kawanabe KyOsai, HyakkiyagyO-zu: Biwa o ou otoko, c. 1879. Ink and color on paper. © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum. Excerpt from Molloy, by Samuel Beckett, copyright © 1955 by Grove Press, Inc. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc., and Faber and Faber Ltd., © The Estate of Samuel Beckett. An earlier version of chapter 3 appeared as Michael Dylan Foster, “Strange Games and Enchanted Science: The Mystery of Kokkuri,” Journal of Asian Studies 65, no. 2 (May 2006): 251–75, © 2006 by the Associ- ation for Asian Studies, Inc. Reprinted with permission. Some material from chapter 5 has appeared previously in Michael Dylan Foster, “The Question of the Slit-Mouthed Woman: Contemporary Legend, the Beauty Industry, and Women’s Weekly Magazines in Japan,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 32, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 699–726, © 2007 by The University of Chicago. Parts of chapter 5 have also appeared in Michael Dylan Foster, “The Otherworlds of Mizuki Shigeru,” in Mechademia, vol. 3, Limits of the Human, ed. Frenchy Lunning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008). -

Folleto De La Exposición (Castellano E Inglés)

Palabras de saludo Message Dentro del marco de las importantes actividades que se desarrollan from the Organizers para conmemorar el 150 Aniversario del establecimiento de relaciones diplomáticas entre España y Japón, es para nosotros un gran honor y alegría el presentar la exposición “Yo¯kai: iconografía de lo fantástico. El Desle Nocturno de los Cien Demonios como génesis de la imagen sobrenatural en Japón”. En Japón, puede encontrarse la gura de los y o¯ k a i desde tiempos tan antiguos como el Periodo Muromachi (siglos XIV a XVI, aproximadamente), retratados en el llamado Hyakki Yagyo¯ Emaki (Rollo ilustrado del Desle Nocturno de los Cien Demonios) que se dibujó entonces, y se cree que este tipo de criaturas nacieron del temor reverencioso y la intranquilidad de ánimo que producían fenómenos incontrolables de la Naturaleza, como las catástrofes naturales, los cambios We are very pleased and honored to present one of the most important atmosféricos o las enfermedades contagiosas. Las criaturas de formas projects commemorating the 150th anniversary of diplomatic relations anómalas que aquí contemplamos continuaron siendo dibujadas tomando between Japan and Spain: the exhibition “Yokai: Iconography of the como modelo este tipo de Hyakki Yagyo¯ Emaki, dando a luz otras nuevas Fantastical. The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons as the Source of de lo más diverso y, a lo largo del Período Edo (primeros del siglo XVII Supernatural Imagery in Japan.” a mediados del XIX), cuando la impresión mediante tacos de madera estaba en su apogeo, la información sobre el particular se vuelve más Depicted as far back as the Muromachi period (fourteenth-sixteenth sistematizada, llegando a difundirse idéntico contenido entre un espectro century) when the Night Parade of One Hundred Demons picture scroll was muy amplio de población. -

COX-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (5.765Mb)

Copyright Copyright by Benjamin Davis Cox 2018 Signature Page The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Davis Cox certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Gods Without Faces Childhood, Religion, and Imagination in Contemporary Japan Committee: ____________________________________ John W. Traphagan, Supervisor ____________________________________ A. Azfar Moin ____________________________________ Oliver Freiberger ____________________________________ Kirsten Cather Title Page Gods Without Faces Childhood, Religion, and Imagination in Contemporary Japan by Benjamin Davis Cox Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Dedication For my mother, who tirelessly read all of my blasphemies, but corrected only my grammar. BB&tt. Acknowledgments Fulbright, CHLA This research was made possible by the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, a Hannah Beiter Graduate Student Research Grant from the Children’s Literature Association, and a grant from the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Endowment in the College of Liberal Arts, University of Texas at Austin. I would additionally like to thank Waseda University for sponsoring my research visa, and in particular Glenda Roberts for helping secure my affiliation. Thank you to the members of my committee—John Traphagan, Azfar Moin, Oliver Freiberger, and Kirsten Cather—for their years of support and intellectual engagement, and to my ‘grand-advisor’ Keith Brown, whose lifetime of work in Mizusawa opened many doors to me that would otherwise have remained firmly but politely shut. I am deeply indebted to the people of Mizusawa for their warmth, kindness, and forbearance. -

Household Altars in Contemporary Japan: Rectifying Buddhist "Ancestor Worship" with Home Décor and Consumer Choice

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Theology & Religious Studies College of Arts and Sciences 2008 Household Altars in Contemporary Japan: Rectifying Buddhist "Ancestor Worship" with Home Décor and Consumer Choice John Nelson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/thrs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, John. Household altars in contemporary Japan: Rectifying Buddhist "Ancestor Worship" with home décor and consumer choice. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies Vol. 35, No. 2 (2008), pp. 305-330. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology & Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 35/2: 305–330 © 2008 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture John Nelson Household Altars in Contemporary Japan Rectifying Buddhist “Ancestor Worship” with Home Décor and Consumer Choice In Japan, where organized religion is increasingly viewed with a critical eye, one of the country’s most enduring social and religious traditions—commem- orating ancestral spirits—is undergoing rapid change. The highly competitive market for household altars is the source of innovative and sometimes radi- cal concepts that represent a paradigm shift in how families and individuals should interact with ancestral spirits. No longer catering to guidelines from mainstream Buddhist denominations about altar style and function, compa- nies building and marketing contemporary altars (gendai butsudan) present a highly-refined product that not only harmonizes with modern interior designs but also emphasizes individual preferences and spirituality in how the altar is conceptualized and used. -

Banchō Sarayashiki

Banchō Sarayashiki Daihachi and Okiku. A one-act Kabuki version was created in 1850 by Segawa Joko III, under the title Minoriyoshi Kogane no Kikuzuki, which debuted at the Nakamura-za theater and starred Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII and Ichikawa Kodanji IV in the roles of Tetsuzan and Okiku. This one-act adaptation was not popular, and quickly folded, until it was revived in June 1971 at the Shinbashi Enbujō theater, starring the popular combination of Kataoka Takao and Bando Tamasaburō V in the roles of Tetsuzan and Okiku. The most familiar and popular adaptation of Banchō Sarayashiki, written by Okamoto Kido, debuted in Febru- ary 1916 at the Hongō-za theater, starring Ichikawa Sadanji II and Ichikawa Shōchō II in the roles of Lord Harima and Okiku. It was a modern version of the clas- sic ghost story in which the horror tale was replaced by a deep psychological study of the two characters' motiva- tions. Another adaptation was made in 2002, in Story 4 of the Japanese television drama Kaidan Hyaku Shosetsu.*[1] 2 Plot summary Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's portrait of Okiku. 2.1 Folk version Banchō Sarayashiki or Bancho Sarayashi (番町⽫屋 Once there was a beautiful servant named Okiku. She 敷 The Dish Mansion at Banchō) is a Japanese ghost story worked for the samurai Aoyama Tessan. Okiku often re- (kaidan) of broken trust and broken promises, leading to fused his amorous advances, so he tricked her into be- a dismal fate. lieving that she had carelessly lost one of the family's ten precious delft plates. -

In the Depths of Groves

ANN LOFQUIST TRANE DEVORE 1 Froudland Alamo Creek Lower Grove: hen I was a child, I spent much of my time North View III, 2012 In the Depths trespassing. I grew up in the countryside, Oil on Canvas, 7 1/ x 16 in. 2 W in a cow town surrounded by chicken of Groves ranches and dairy farms. That was Sonoma County, in Northern California, north of the San Francisco Bay Area, before the grapes became ubiquitous and before the tech boom gave much of the county the dull contour of an upscale bedroom community. Most of the cattle in the area where I grew up were free range, which meant that the hills and felds surround- ing my house were easily walkable. There were still plenty of woods amid the open felds. Oak, bay, and buckeye trees grew thick around the creeks at the feet of the hills, while monumental eucalyptus windbreaks dominated the hori- zon. Small reservoirs—good for bass fshing—dotted the hills. Hilltops were defned by small outcroppings of igne- ous rocks, like remnants of some prehistoric barrow, with signs of hawk habitation scattered about—mouse skulls, hawk shit, and the winged remnants of other birds. Hills not covered with rocks would often be topped with small oak groves or, sometimes, dense oak forests that, from a distance, resembled nothing so much as bunched broccoli. Up the road from my house—past the pine forest that was once a Christmas tree farm—was a small eucalyptus grove split down the middle by the shallow creek that ran through it. -

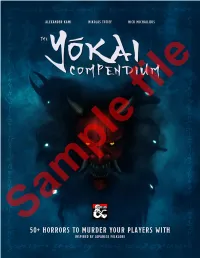

The Yōkai Compendium

Sample file FROM THE CREATORS OF & COMES ō Sample file Table of Contents Shirime . 36 Introduction 3 Suiko . 37 Tanuki . 38 Bestiary Bake-danuki . 38 Abura Sumashi . 4 Fukuro Mujina . 38 Akabeko . 5 Korōri . 38 Akaname . 6 Tengu . 40 Ama . 7 Daitengu . 40 Amahime . 7 Kotengu . 41 Amarie . 8 Tennin . 42 Baku . 9 Tsuchigumo . 43 Chirizuka . 10 Tsuchinoko . 44 Hashihime . 11 Tsukumogami . 45 A Hashihime's Lair . 12 Abumi Guchi . 45 Hinowa . 13 Chōchin Obake . 45 Kata-waguruma . 13 Jatai . 45 Wanyūdō . 14 Kasa Obake . 45 Itsumade . 15 Kyōrinrin . 45 Jorōgumo . 16 Shiro Uneri . 45 Kappa . 17 Shōgorō . 45 Kitsune . 18 Zorigami . 45 Ashireiko . 18 Ubume . 51 Chiko . 18 Umibōzu . 52 Kiko . 19 Ushi-oni . 53 Tenko . 20 An Ushi-oni's Lair . 53 Kūko . 21 Kurote . 22 Sorted Creatures 54 Ningyo . 23 Creatures by CR . 54 Nurikabe . 24 Creatures by Terrain . 55 Ōmukade . 25 Creatures by Type . 57 Oni . 27 Pronunciation & Translation Table . 58 Amanojaku . 27 Dodomeki . 28 Hannya . ..