People in Villages Are Not Aware of the Services Available in the Hospitals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renewable Energy Data in Lao PDR

EAST and Southeast Asia Renewable Energy Statistic Training Workshop Renewable Energy Data in Lao PDR Institute of Renewable Energy Promotion Ministry of Energy and Mines 12-14/12/2016 Bangkok, Thailand Outline 1. Introduction 2. Current energy situation and outlook. 3. Power potential in Lao PDR 4. Energy Sector Policy 5. Conclusion BASIC FACTS ABOUT LAOS • Area : 236,800 km2 • Capital: Vientiane • Population 2015 – Total 6.5 millions – Density 27 person/km2 • Total Share of GDP 2015 – GDP per Capita 1,947 US$ – Growth rate of GDP: 7.56% • Share of GDP 2015 –Agricultural: 21.80% –Industry: 32.70% –Services: 35.95% –Taxes on products and Import duties, net: 9.55% 1. Current Energy Situation and Outlook • Energy Development in Lao PDR has been rapidly increasing in parallel with the domestic demand. Additionally, Lao Government has supported and encouraged private to invest in energy sector. Compare of increasing by the year of 2010, the total install capacity is increased from 2,546.7 MW to 5,806 MW in 2016. 1. Current Energy Situation and Outlook 1. Current Energy Situation and Outlook Energy Supply: Lao PDR has potential of Hydropower about 28,600 MW with 409 projects Project Install Capacity Energy Generation Amount (MW) (GWh/year) Existing Projects 40 6,290 33,590 Under construction Projects and 50 5,820 27,502 expect to complete construction by 2020 Expect to complete construction 35 4,147 20,106 by 2025 Expect to complete construction 58 4,434 18,272 by 2030 MOU signed 246 8,480 30,119 Total 429 29,171 129,589 Sourced: The 6th Report on Hydropower Development Projects in Lao PDR (30 June 2016), by DEPP NONE Hydro RE projects WIND: 2000-3000 MW • 600 MW (1st phase: 250MW) under negotiation for development in Sekong Prov. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report Preparing the Ban Sok

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41450 February 2012 Preparing the Ban Sok–Pleiku Power Transmission Project in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) Annex 3.1: Initial Environmental Examination in Lao PDR (500 KV Transmission Line and Substation) Prepared by Électricité de France Paris, France For Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Ban-sok Pleiku Project CONTRACT DOCUMENTS – TRANSMISSION LINE Package – LaoPDR FINAL REPORT 500kV TRANSMISSION SYSTEM PROJECT ANNEX 3.1 – 500kV TRANSMISSION LINE & SUBSTATION Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) In Lao PDR Annex 3.1– TL & S/S IEE in Lao PDR ADB TA 6481‐REG BAN‐SOK (HATXAN) PLEIKU POWER TRANSMISSION PROJECT 500 kV TRANSMISSION LINE AND SUBSTATION – FEASIBILITY STUDY Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) For: Ban Hatxan Substation and 59km 500kVA Double Circuit Three Phased Transmission Line from Hatxan Substation to the Vietnam Border. Draft: Nov. 2010 Prepared by Electricite du France and Earth Systems Lao on behalf of Electricite du Lao (EDL), Ministry of Energy and Mines Lao PDR and for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The views expressed in this IEE do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. BAN SOK – PLEIKU DRAFT FINAL REPORT_IEE_LAO PDR SIDE LAO PDR / VIETNAM Asian Development Bank CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARING THE BAN-SOK PLEIKU POWER TRANSMISSION PROJECT 500 kV OHL_TA 6481-REG Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... -

Vientiane Times City Authorities, JICA Confer on UNFPA to Employ New Strategy Development Planning for Helping Women, Girls

th 40 Lao PDR 2/12/1975-2/12/2015 VientianeThe FirstTimes National English Language Newspaper WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 9, 2015 ISSUE 286 4500 kip Thai princess visits Laos to enhance Huaphan vehicle caravan ties, mutual understanding expected to grow Souknilundon a major historical role in the Times Reporters Southivongnorath struggle for the independence of the Lao people in the past. Her Royal Highness Princess A vehicle caravan travelling The caravan shall depart Maha Chakri Sirindhorn of to the northern provinces from Vientiane before passing through Thailand arrived in Vientiane December 11-15 this year should Xieng Khuang province on yesterday for a two-day double in size compared to the its way to Vienxay district of official visit to Laos, aimed previous year, according to the Huaphan province under the at enhancing bilateral ties Ministry of Information, Culture theme “Return to the Birthplace- between the two neighbours and Tourism yesterday. Glorification to the revolution and mutual understanding The ministry arranged a press of Laos” between the Lao and Thai conference to officially announce Running from December 11- peoples. the caravan to the public. The 15, the trip will start from That Her visit is in response main objective of the activity was Luang Esplanade in the capital to an invitation from Deputy to promote tourism sites among and head up through Xieng Prime Minister and Minister local people and foreign visitors Khuang on its way to Huaphan of Foreign Affairs Thongloun or foreign residents in Laos. province. Sisoulith, the Lao Ministry of They said it is also part of The caravan group will Foreign Affairs said in a press celebrating the 40th anniversary visit the Kaysone Phomvihane release. -

Typhoon Haima in the Lao People's Democratic Republic

TYPHOON HAIMA IN THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Joint Damage, Losses and Needs Assessment – August, 2011 A Report prepared by the Government of the Lao PDR with support from the ADB , ADPC, FAO , GFDRR, Save the Children, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN-HABITAT, WFP, WHO, World Bank, World Vision, and WSP Lao People's Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity TYPHOON HAIMA JOINT DAMAGE, LOSSES AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT (JDLNA) *** October 2011 A Report prepared by the Government of the Lao PDR With support from the ADB, ADPC, FAO, GFDRR , Save the Children, UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN- HABITAT, WFP ,WHO, World Bank, World Vision, AND WSP Vientiane, August 29, 2011 Page i Foreword On June 24-25, 2011, Typhoon Haima hit the Northern and Central parts of the Lao PDR causing heavy rain, widespread flooding and serious erosion in the provinces of Xiengkhouang, Xayaboury, Vientiane and Bolikhamxay. The typhoon caused severe damage and losses to the basic infrastructure, especially to productive areas, the irrigation system, roads and bridges, hospitals, and schools. Further, the typhoon disrupted the local people’s livelihoods, assets and properties. The poor and vulnerable groups of people are most affected by the typhoon. Without immediate recovery efforts, its consequences will gravely compromise the development efforts undertaken so far by the government, seriously set back economic dynamism, and further jeopardise the already very precarious situation in some of the provinces that were hard hit by the typhoon. A Joint Damage, Losses and Needs Assessment (JDLNA) was undertaken, with field visit to the four most affected provinces from 25th July to 5th August 2011. -

1 Lao People's Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Ministry of Health Department of Planning

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Ministry of Health Department of Planning and Cooperation GMS Health Security Project Cross border checkpoint (Points of entry) survey report The department of communicable disease control of the ministry of health conducted the survey of the border checkpoints during the period of June to September 2019. The survey was to implement one of the activities of the annual operation plan 2019 supported by the health security project and funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The overall objectives of the survey were to have the information about the operation and the capacity of the border checkpoints in meeting the core capacity of the International Health Regulation for the public health emergency operation. Specific objectives were to: Map out the location/site of each checkpoint Assess the availability of health facilities, equipment, numbers of health staff and location of health checking counter and SOP Collect the information of traffic volume crossing the border checkpoints Assess the preparedness and response capacity at the PoE See the gaps, constraints and make the recommendation for an improved capacity in disease outbreak control at the border checkpoint I. Border checkpoints in the survey: A totally 27 selected points of entry surveyed which included 4 international airports, 23 ground crossing points and 3 local traditional checkpoints shown in the table below: No. Province District Check point name Shared border Sikhottabong Wattai International -

Lao EU-FLEGT

Lao-EU FLEGT NEWSLETTER FLEGT stakeholders met to discuss the draft Timber FLEGT Standing Office (FSO) updated the stakeholders From 10 to 21 February Department of Forest Inspection A Joint Provincial Coordination Committee (PCC) the areas presented, the following two regions in Attapeu Legality Definitions (TLD) and other elements of the on the Lao-EU FLEGT VPA, related policy reforms and (DOFI) hosted a training on Operational Logging and meeting with the participation of PCC Attapeu and PCC were selected to be suitable for TLAS testing: Namkong timber legality assurance system (TLAS) at the February the roadmap until the next negotiation. Following the key Degradation Monitoring (OLDM), with its objective to Khammouane was held in Thakhek on March 5, 2020. 3 and Sanamxay District, located in the previous flooded Negotiation Support and Development Committee points of the last negotiation, the stakeholders discussed have an operational system in place, delivering alerts in The PCC of Khammouane and Attapeu were established area. (NSDC) meeting in preparation for the fourth negotiation on the proposal of piloting of supply chain control and near real-time about suspicious activities outside to coordinate with the Provincial Steering Committee round with the European Union (EU). compliance verification of TLAS elements, especially of conversion areas. (PSC), the National Steering Committee (NSC) and other Both of the chairman, Mr. Bounchanh Xaypanya, Director TLD 2, 7 and 8 in an infrastructure project in related stakeholders in the implementation of the piloting General of Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office Issue May 2020 Photo: © Phetsaphone Thanasack The 3rd negotiation round in June 2019 provided the Khammouane and Attapeu, the FLEGT pilot provinces. -

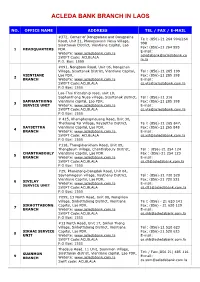

Acleda Bank Branch in Laos

ACLEDA BANK BRANCH IN LAOS NO. OFFICE NAME ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL #372, Corner of Dongpalane and Dongpaina Te l: (856)-21 264 994/264 Road, Unit 21, Phonesavanh Neua Village, 998 Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Lao Fax: (856)-21 264 995 1 HEADQUARTERS PDR. E-mail: Website: www.acledabank.com.la [email protected] SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA m.la P.O. Box: 1555 #091, Nongborn Road, Unit 06, Nongchan Village, Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Tel : (856)-21 285 199 VIENTIANE Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 2 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 Lao-Thai friendship road, unit 10, Saphanthong Nuea village, Sisattanak district, Tel : (856)-21 316 SAPHANTHONG Vientiane capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 3 SERVICE UNIT Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 # 415, Khamphengmeuang Road, Unit 30, Thatluang Tai Village, Xaysettha District, Te l: (856)-21 265 847, XAYSETTHA Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 265 848 4 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la, E-mail: SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #118, Thongkhankham Road, Unit 09, Thongtoum Village, Chanthabouly District, Tel : (856)-21 254 124 CHANTHABOULY Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Fax : (856)-21 254 123 5 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #29, Phonetong-Dongdok Road, Unit 04, Saynamngeun village, Xaythany District, Tel : (856)-21 720 520 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. -

Sustainable Rattan Production

2011 Sustainable Rattan Production Manual for Small and Medium Enterprises in Lao PDR THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY : The European Union through WWF’s rattan project “Establishing a Sustainable Production System for Rattan Products in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam” AU T HOR : Vilasack Xayaphet CONSUL T AN T : Ms. Vilayvanh Saysanavongphet EDI T OR FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE : Frazer Henderson EDI T OR : Thibault Ledecq GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOU T : Noy Promsouvanh PHO T OGRAPHER : Noy Promsouvanh PRINTING HOUSE : Naxay Services Sign and Printing COPYRIGH T : 2011- WWF/LNCCI This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WWF and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. 2011 Sustainable Rattan Production Manual for Small and Medium Enterprises in Lao PDR NOTE Vientiane, 11 November 2011 Dear readers, With the support of WWF Laos, the Lao National Chamber of Commerce has produced a manual on “ Sustainable Rattan Production for the Lao rattan SMEs” reflecting the experiences gained during the different projects on building a sustainable value chain for Lao rattan sector aiming at linking local producers with global value chains which will create new local income opportunities and employment, while simultaneously alleviating poverty and protecting natural resources. This manual is an important reference on how Lao rattan businesses could move on to a sustainable production. All the essential elements are ex- plained from where to get sustainable rattan to export. As the world mar- ketplace changes every year, we encourage them to move forward and be part of these changes and get the benefits from that. -

Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care Services in Lao People's Democratic Republic

Investing the Marginal Dollar for Maternal and Newborn Health: Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care services in Lao People's Democratic Republic Steeve Ebener, PhD 1 and Karin Stenberg, MSc 2 1 Consultant, Gaia GeoSystems, The Philippines 2 Technical Officer, Department of Health Systems Governance and Financing, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care services in Lao PDR © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (http://www.who.int ) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected] ). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/index.html ). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Municipal Solid Waste Management 4-1 4.1 the Capital of Vientiane

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Data Collection Survey on Waste Management Sector in The Lao People’s Democratic Republic Final Report February 2021 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EX Research Institute Ltd. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. GE KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. JR 21-004 Locations of Survey Target Areas 1. Meeting at Transfer Station 2. Vang Vieng Landfill Site 3. Savannakhet UDAA 4. Online meeting with MONRE’s Vice Minister 5. Outlook of Health-care Waste Incinerator, 6. Final disposal site in Xayaboury District Luang Prabang District 7. Factory visit to EPOCH Co., Ltd. 8. DFR Joint-Workshop (online) Survey Photos Executive Summary 1. Background and objective In the Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos), the remaining capacity of the final disposal site in cities is becoming insufficient due to the influence of the population increase and the progress of urbanization in recent years. The waste collection rate remains at a low level. In many cases, medical waste and hazardous waste are also dumped in municipal waste disposal sites and vacant lots without proper treatment. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) is in charge of formulating policies and plans for overall environmental measures, including waste management, and coordinating related ministries and agencies. On the other hand, the actual waste management work is under the jurisdiction of different ministries and agencies depending on the type of waste. In the central government, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) oversees general waste, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MOIC) is in charge of industrial waste, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) is in charge of medical waste. -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Land Concessions, Land Tenure, and Livelihood Change: Plantation Development in Attapeu Province, Southern Laos

Land Concessions, Land Tenure, and Livelihood Change: Plantation Development in Attapeu Province, Southern Laos Miles Kenney-Lazar Fulbright Scholar & Visiting Research Affiliate Faculty of Forestry, National University of Laos [email protected] Table of Contents Abbreviations 3 Glossary of Lao Language Terms 4 Acknowledgments 5 Executive Summary 6 1. Introduction: Land Concessions in Question 8 2. Methods 9 3. The 2009 Southeast Asian Games: Sports, Aid, and Land 10 4. Hoàng Anh Gia Lai: Growth, Expansion, and International Investment 13 5. Project Description 17 6. Implementation 22 6.1 Governmental Facilitation 22 6.2 Consultation and Negotiation 23 6.2 Resistance 25 7. Land Tenure Insecurity: Loss and Compensation 28 7.1 Loss 28 7.2 Compensation 33 8. Changing Livelihoods: From Land User to Land Laborer 37 8.1 Pre-concession Livelihoods 37 8.2 Changing Livelihoods 39 8.2 Alternative Livelihoods 42 9. Ways Forward 45 9.1 Land Use Zoning and Concession Guidelines 45 9.3 Increased Land Tenure Security 46 9.5 Farmer Awareness Campaigns 46 9.5 Improved Mitigation 47 2 Abbreviations Asian Development Bank ADB Association of Southeast Asian Nations ASEAN Chief Executive Officer CEO Department of Forestry DOF Department of Planning and Investment DPI District Agriculture and Forestry Office DAFO Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESIA Geographic Information System GIS Geographic Positioning System GPS Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (German Technical Cooperation) GTZ Hoàng Anh Gia Lai Joint Stock Company