Now Letˇs Multiply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

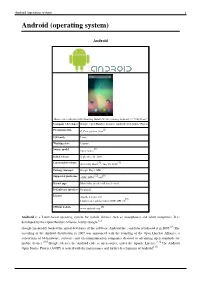

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Nexus S with Google running Android 2.3 "Gingerbread" Company / developer Google Inc., Open Handset Alliance [1] Programmed in C (core), C++ (some third-party libraries), Java (UI) Working state Current [2] Source model Free and open source software (3.0 is currently in closed development) Initial release 21 October 2008 Latest stable release Tablets: [3] 3.0.1 (Honeycomb) Phones: [3] 2.3.3 (Gingerbread) / 24 February 2011 [4] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, Power, x86 Kernel type Monolithic, modified Linux kernel Default user interface Graphical [5] License Apache 2.0, Linux kernel patches are under GPL v2 Official website [www.android.com www.android.com] Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications.[6] [7] Google Inc. purchased the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., in 2005.[8] Android's mobile operating system is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel. Google and other members of the Open Handset Alliance collaborated on Android's development and release.[9] [10] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[11] The Android operating system is the world's best-selling Smartphone platform.[12] [13] Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. There are currently over 150,000 apps available for Android.[14] [15] Android Market is the online app store run by Google, though apps can also be downloaded from third-party sites. -

History and Evolution of the Android OS

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector CHAPTER 1 History and Evolution of the Android OS I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this. —Steve Jobs, Apple Inc. Android, Inc. started with a clear mission by its creators. According to Andy Rubin, one of Android’s founders, Android Inc. was to develop “smarter mobile devices that are more aware of its owner’s location and preferences.” Rubin further stated, “If people are smart, that information starts getting aggregated into consumer products.” The year was 2003 and the location was Palo Alto, California. This was the year Android was born. While Android, Inc. started operations secretly, today the entire world knows about Android. It is no secret that Android is an operating system (OS) for modern day smartphones, tablets, and soon-to-be laptops, but what exactly does that mean? What did Android used to look like? How has it gotten where it is today? All of these questions and more will be answered in this brief chapter. Origins Android first appeared on the technology radar in 2005 when Google, the multibillion- dollar technology company, purchased Android, Inc. At the time, not much was known about Android and what Google intended on doing with it. Information was sparse until 2007, when Google announced the world’s first truly open platform for mobile devices. The First Distribution of Android On November 5, 2007, a press release from the Open Handset Alliance set the stage for the future of the Android platform. -

Essential Phone on Its Way to Early Adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, the Mercury News

Essential Phone on its way to early adopters 24 August 2017, by Seung Lee, The Mercury News this week in a press briefing in Essential's headquarters in Palo Alto. "People have neglected hardware for years, decades. The rest of the venture business is focused on software, on service." Essential wanted to make a timeless, high-powered phone, according to Rubin. Its bezel-less and logo- less design is reinforced by titanium parts, stronger than the industry standard aluminum parts, and a ceramic exterior. It has no buttons in its front display but has a fingerprint scanner on the back. The company is also making accessories, like an attachable 360-degree camera, and the Phone will work with products from its competition, such as the Apple Homekit. Essential, the new smartphone company founded by Android operating system creator Andy Rubin, "How do you build technology that consumers are is planning to ship its first pre-ordered flagship willing to invest in?" asked Rubin. "Inter-operability smartphones soon. The general launch date for is really, really important. We acknowledge that, the Essential Phone remains unknown, despite and we inter-operate with companies even if they months of publicity and continued intrigue among are our competitors." Silicon Valley's gadget-loving circles. Recently, Essential's exclusive carrier Sprint announced it While the 5.7-inch phone feels denser than its will open Phone pre-orders on its own website and Apple and Samsung counterparts, it is bereft of stores. Essential opened up pre-orders on its bloatware - rarely used default apps that are website in May when the product was first common in new smartphones. -

Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017

Week Ending: Weekly Wireless Report August 18, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Inside This Issue: August 16, 2017 This Week’s Stories Apple is finally getting serious about original TV programming. Apple Is On The Hunt For Original TV Shows Two Apple executives have been meeting with Hollywood agents and producers to hear pitches about possible shows for Apple to buy, according to two producers who have met with them. Facebook Is Building A New $750 Million Data Center In Ohio The execs, Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg, were hired from Sony Pictures Television in June to oversee Apple's video programming. Products & Services New Apple, Samsung These pitch meetings have placed Apple in direct competition with Netflix, HBO and other Smartphone Challenger Is Finally distributors. Available For Pre-Order Some producers are eager to work with Apple, sensing a first-mover advantage. Others have a lot of YouTube TV Now Available To questions about how Apple will distribute its shows. When "House of Cards" debuted on Netflix, 50% Of U.S. Households marking the streaming service's entrance into original programming, the service already had a large catalog of licensed programming. Apple, Aetna Hold Secret Meetings To Bring Apple Watch To Millions Of Aetna Customers Apple doesn't have that -- but it does have iPhones in hundreds of millions of hands. Emerging Technology The meetings were first reported by The Wall Street Journal on Wednesday. Apple is said to be AI Is Taking Over The Cloud budgeting about $1 billion to acquire and produce original TV shows over the next year, according to the Journal. -

Should Google Be Taken at Its Word?

CAN GOOGLE BE TRUSTED? SHOULD GOOGLE BE TAKEN AT ITS WORD? IF SO, WHICH ONE? GOOGLE RECENTLY POSTED ABOUT “THE PRINCIPLES THAT HAVE GUIDED US FROM THE BEGINNING.” THE FIVE PRINCIPLES ARE: DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER. PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE. LABEL ADVERTISEMENTS CLEARLY. BE TRANSPARENT. LOYALTY, NOT LOCK-IN. BUT, CAN GOOGLE BE TAKEN AT ITS WORD? AND IF SO, WHICH ONE? HERE’S A LOOK AT WHAT GOOGLE EXECUTIVES HAVE SAID ABOUT THESE PRINCIPLES IN THE PAST. DECIDE FOR YOURSELF WHO TO TRUST. “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “I actually think most people don't want Google to answer their questions. They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.” Eric Schmidt The Wall Street Journal 8/14/10 EXEC. CHAIRMAN ERIC SCHMIDT “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers.” Larry Page & Sergey Brin Stanford Thesis 1998 FOUNDERS BRIN & PAGE “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “The Google policy on a lot of things is to get right up to the creepy line.” Eric Schmidt at the Washington Ideas Forum 10/1/10 EXEC. CHAIRMAN ERIC SCHMIDT “DO WHAT’S BEST FOR THE USER” “We don’t monetize the thing we create…We monetize the people that use it. The more people use our products,0 the more opportunity we have to advertise to them.” Andy Rubin In the Plex SVP OF MOBILE ANDY RUBIN “PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE” “PROVIDE THE MOST RELEVANT ANSWERS AS QUICKLY -

Google's Management Change and the Enterprise

STEPHEN E ARNOLD APRIL 20, 2011 Google’s Management Change and the Enterprise Google completed its management shift in April 2011 with several bold moves. The story of founder Larry Page’s move to the pilot’s seat appeared in most news, financial, and consumer communication channels. American business executives have a status similar to that accorded film and rock and roll stars. An aspect of the changes implemented in his first week on the job as the top Googler included some surprising, and potentially far reaching shifts in the $30 billion search and advertising giant. First, a number of executive shifts took place. Jonathan Rosenberg, the senior vice president of product management, left the company on the day Mr. Page officially assumed Mr. Schmidt’s duties. Mr. Rosenberg, a bright and engaging professional, was not a technologist’s technologist. I would characterize Mr. Rosenberg as a manager and a sales professional. The rumor that Mr. Rosenberg and Mr. Schmidt would write a book about their experiences at Google surfaced and then disappeared. The ideas was intriguing and reinforced the Charlie Sheen-magnetism senior business executives engender in the post-crash US. The echo from the door snicking shut had not faded when Mr. Page announced a shift in the top management of the company. For example, Sundar Pichai http://www.thechromesource.com/sundar-pichai- chrome-and-chrome-os-vp-being-courted-by-twitter/ (who has been at Google since 2004 and was allegedly recruited by Twitter) took over Chrome, Google’s Web browser and possible mobile device operating system alternative to Android. -

Android, Iphone Competitors Wage Weak Battle 22 December 2010, by Troy Wolverton

Android, iPhone competitors wage weak battle 22 December 2010, By Troy Wolverton In the smart phone business, the conventional Phone 7 still comes up short, lacking features such wisdom is that everyone is battling for third place as multitasking and copy-and-paste. Belfiore's behind Google and Apple. response was to note that Windows Phone lets users take pictures without having to unlock their But after listening to briefings from some of their phones, something they couldn't do on many other competitors, I'm beginning to think Google and devices. Apple may soon have the market to themselves. In other words, in the not-too-distant future, your While that's a nice feature, it's not at the top of choices of a smart phone may well be an iPhone or most smart-phone customers' wish lists. one running Google's Android - and that's it. HP's webOS, which it acquired when it bought At the D: Dive Into Mobile conference in San Palm, appears to be in even bigger trouble than Francisco earlier this month, representatives of Windows Phone 7. I loved webOS when I tested it Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard and Research In out, but Palm struggled to establish it in the Motion were brought on stage to talk about their marketplace and largely failed to lure software companies' smart phone strategies. But under developers to the platform. Questioned about what questioning from the hosts and the audience, none happened to Palm, HP executive Jon Rubinstein, could articulate a clear or persuasive case for how who was Palm's CEO before it was acquired by HP, their platforms will survive the coming shakeout. -

Litigator of the Week

Litigator of the Week: Using Shareholder Litigation to Push for Policy Changes and a $310M, 10-Year Commitment to Diversity at Google’s Parent Company "I’m excited to see the opportunities that are created for women because of this settlement," says Julie Goldsmith Reiser of Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll. By Ross Todd October 2, 2020 When Google parent company Alphabet announced a $310 million commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion efforts over the next 10 years, it marked what, if approved, could be the largest ever shareholder derivative settlement and largest #MeToo-related settlement all at once. The deal, which also bars Google affiliates from forcing employees with harassment claims into arbitration and lim- its the reach of non-disclosure agreements, would resolve shareholders derivative claims related to allegations that the tech giant’s board members violated their fiduciary duties by enabling a double standard allowing executives Courtesy photos to sexually harass and discriminate against women without Cohen Milstein’s Julie Goldsmith Reiser consequence. It comes a little less than two years after The New York Times reported, among other things, that the Julie Goldsmith Reiser: The impetus for this case was a company’s board approved a $90 million exit package for bombshell article written in The New York Times reporting Andy Rubin, the executive who headed the development of the Android mobile operating system, after an internal that Google had protected, praised and rewarded Android investigation found a credible sexual harassment claim had platform founder Andy Rubin despite an internal investi- been made against him. gation finding that he had been credibly accused of sexual Julie Goldsmith Reiser of Cohen Milstein Sellers & harassment. -

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Galaxy Nexus, running Android 4.1 "Jelly Bean" Company / developer Google, Open Handset Alliance, Android Open Source Project [1] Programmed in C, C++, python, Java OS family Linux Working state Current [2] Source model Open source Initial release September 20, 2008 [3] [4] Latest stable release 4.1.1 Jelly Bean / July 10, 2012 Package manager Google Play / APK [5] [6] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) Default user interface Graphical License Apache License 2.0 [7] Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [8] Official website www.android.com Android is a Linux-based operating system for mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. It is developed by the Open Handset Alliance, led by Google.[2] Google financially backed the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., and later purchased it in 2005.[9] The unveiling of the Android distribution in 2007 was announced with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of 86 hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices.[10] Google releases the Android code as open-source, under the Apache License.[11] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[12] Android (operating system) 2 Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. Developers write primarily in a customized version of Java.[13] Apps can be downloaded from third-party sites or through online stores such as Google Play (formerly Android Market), the app store run by Google. -

Amended Complaint

19CV341522 Santa Clara – Civil Electronically Filed 1 OTTINI OTTINI INC B & B , . by Superior Court of CA, FrancisA.Bottini,Jr.(SBN175783) County of Santa Clara, 2 AlbertY.Chang(SBN296065) on 8/16/2019 3:18 PM YuryA.Kolesnikov(SBN271173) 3 Reviewed By: R. Walker 7817IvanhoeAvenue,Suite102 Case #19CV341522 LaJolla,California92037 4 Envelope: 3274669 Telephone:(858)914-2001 5 Facsimile:(858)914-2002 Email:[email protected] 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 8 COHENMILSTEINSELLERS&TOLLPLLC JulieGoldsmithReiser( ) 9 MollyBowen( ) 1100NewYorkAvenue,N.W.,Suite500 10 Washington,D.C.20005 11 Telephone:(202)408-4600 Facsimile:(202)408-4699 12 Email:[email protected] [email protected] 13 14 15 [AdditionalCounselonSignaturePage] 16 SUPERIORCOURTOFTHESTATEOFCALIFORNIA INANDFORTHECOUNTYOFSANTACLARA 17 18 INREALPHABETINC.SHAREHOLDER LeadCaseNo.19CV341522 19 DERIVATIVELITIGATION 20 CONSOLIDATED 21 STOCKHOLDERDERIVATIVE ThisDocumentRelatesto: COMPLAINTFOR: 22 DEMANDFUTILITYACTION (1)BREACHOFFIDUCIARYDUTY; 23 (2)UNJUSTENRICHMENT; (3)CORPORATEWASTE;and 24 (4)ABUSEOFCONTROL 25 JURYTRIALDEMANDED 26 27 PUBLIC-REDACTSMATERIALSFROMCONDITIONALLYSEALEDRECORD 28 CONSOLIDATEDSTOCKHOLDERDERIVATIVECOMPLAINT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 3 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................................... 11 4 III. PARTIES ................................................................................................................. -

Android (Operating System) 10.1 Introduction: Android Is a Mobile

Page 1 of 9 Android (operating system) 10.1 Introduction: Android is a mobile operating system (OS) based on the Linux kernel and currently developed by Google. With a user interface based on direct manipulation, Android is designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers, with specialized user interfaces for televisions (Android TV), cars (Android Auto), and wrist watches (Android Wear). The OS uses touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching, and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects, and a virtual keyboard. Despite being primarily designed for touchscreen input, it also has been used in game consoles, digital cameras, and other electronics. Android is the most popular mobile OS. As of 2013, Android devices sell more than Windows, iOS, and Mac OS devices combined,[14][15][16][17] with sales in 2012, 2013 and 2014[18] close to the installed base of all PCs.[19] As of July 2013 the Google Play store has had over 1 million Android apps published, and over 50 billion apps downloaded.[20] A developer survey conducted in April–May 2013 found that 71% of mobile developers develop for Android.[21] At Google I/O 2014, the company revealed that there were over 1 billion active monthly Android users (that have been active for 30 days), up from 538 million in June 2013.[22] Android's source code is released by Google under open source licenses, although most Android devices ultimately ship with a combination of open source and proprietary software.[3] -

The Economic Impact of the Robotic Revolution

The Economic Impact of the Robotic Revolution by Colin Lewis , February 19, 2014 Whilst the word ‘robot’ generally conjures up visions of humanoids with superior intelligence, this science fiction image tends to forget the other type of robots: machines that carry out complicated motions and tasks, such as automated software processes1, industrial robots, unmanned vehicles (driverless cars, drones) or even prosthetics. And it is principally the programmable machine robots that are among the robotic advances being acquired by major companies across the globe2. These are also the robotic technologies that are disrupting commercial production and employment, and will likely continue to do so over the remainder of this decade. Many economists and technophobes claim automation and technological progress has broad implications for the shape of the production function, inequality, and macroeconomic dynamics. However, robotics is also adding hundreds of thousands of jobs to the payroll across the globe, and it may just be that people have not yet acclimatized to the new jobs and skills required to do them. Job displacement and skill gaps In his magical science fiction classic, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams wrote about the ‘B’ Ark. The ‘B’ Ark was one of three giant space ships built to take people off the ‘doomed’ planet and relocate them on a new one. The inhabitants of ‘B’ Ark included: “tired TV producers, insurance salesmen, personnel officers, security guards, public relations executives, management consultants, account