Android and the Demise of Operating System-Based Power: Firm Strategy and Platform Control in the Post-PC World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“El Valor Del Comercio Electrónico En El Siglo Xxi”

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DEL ESTADO DE MÉXICO UNIDAD ACADÉMICA PROFESIONAL CUAUTITLÁN IZCALLI “EL VALOR DEL COMERCIO ELECTRÓNICO EN EL SIGLO XXI”. TESINA QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN NEGOCIOS INTERNACIONALES PRESENTA: JOSÉ JUAN LÓPEZ FERNÁNDEZ ASESOR: M. EN C. ED. ENOC GUTIÉRREZ PALLARES CUAUTITLÁN IZCALLI, ESTADO DE MÉXICO. DICIEMBRE DE 2018 “Nunca consideres el estudio como una obligación, sino como una oportunidad para penetrar en el bello y maravilloso mundo del saber.” - Albert Einstein RESUMEN El presente trabajo realiza el estudio del comercio electrónico y la forma en que ha ido mejorando desde su aparición, al igual que algunos de los métodos y herramientas que se utilizan actualmente en compañías importantes del comercio electrónico, como Amazon, la cual es una tendencia presente en las empresas de comercio electrónico a nivel mundial. En el primer capítulo se describe la historia del comercio electrónico, la definición, así como las ventajas y desventajas, programas y modelos, esto para comenzar a relacionarnos con esta rama del comercio. El segundo capítulo señalará algunos tipos de tecnologías, conceptos más relevantes del marketing y logística, aparte de modelos de seguridad que se llevan dentro de una compañía de comercio electrónico, y en el tercer capítulo se concluyen con casos de estudio de algunas de las compañías reconocidas dentro del comercio electrónico. Con este contenido se desea obtener dos resultados: el primero es que resuelva aquellas dudas sobre algún tema del comercio electrónico que desconozca la persona que la revise, y el segundo es que asimismo el interesado que vea el contenido también le sirva como guía, para que de esta forma implemente las técnicas vistas si es que tiene algún plan de realizar algún negocio en internet. -

Mobile Platform Security Architectures: Software

Lecture 3 MOBILE SOFTWARE PLATFORM SECURITY You will be learning: . General model for mobile platform security Key security techniques and general architecture . Comparison of four systems Android, iOS, MeeGo (MSSF), Symbian 2 Mobile platforms revisited . Android ~2007 . Java ME ~2001 “feature phones”: 3 billion devices! Not in smartphone platforms . Symbian ~2004 First “smartphone” OS 3 Mobile platforms revisited . iOS ~2007 iP* devices; BSD-based . MeeGo ~2010 Linux-based MSSF (security architecture) . Windows Phone ~2010 . ... 4 Symbian . First widely deployed smartphone OS EPOC OS for Psion devices (1990s) . Microkernel architecture: OS components as user space services Accessed via Inter-process communication (IPC) 5 Symbian Platform Security . Introduced in ~2004 . Apps distributed via Nokia Store Sideloading supported . Permissions are called ‘capabilities’, fixed set (21) 4 Groups: User, System, Restricted, Manufacturer 6 Symbian Platform Security . Applications identified by: UID from protected range, based on trusted code signature Or UID picked by developer from unprotected range Optionally, vendor ID (VID), based on trusted code signature 7 Apple iOS . Native application development in Objective C Web applications on Webkit . Based on Darwin + TrustedBSD kernel extension TrustedBSD implements Mandatory Access Control Darwin also used in Mac OS X 8 iOS Platform Security . Apps distributed via iTunes App Store . One centralized signature authority Apple software vs. third party software . Runtime protection All third-party software sandboxed with same profile Permissions: ”entitlements” (post iOS 6) Contextual permission prompts: e.g. location 9 MeeGo . Linux-based open source OS, Intel, Nokia, Linux Foundation Evolved from Maemo and Moblin . Application development in Qt/C++ . Partially buried, but lives on Linux Foundation shifted to HTML5- based Tizen MeeGo -> Mer -> Jolla’s Sailfish OS 10 MeeGo Platform Security . -

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/Ejss.2020.08.03.002

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/ejss.2020.08.03.002 EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES www.eurasianpublications.com XIAOMI – TRANSFORMING THE COMPETITIVE SMARTPHONE MARKET TO BECOME A MAJOR PLAYER Leo Sun HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Chung Tin Fah Corresponding Author: HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Received: August 12, 2020 Accepted: September 2, 2020 Abstract Over the past six years, (between the period 2014 -2019), China's electronic information industry and mobile Internet industry has morphed rapidly in line with its economic performance. This is attributable to the strong cooperation between smart phones and the mobile Internet, capitalizing on the rapid development of mobile terminal functions. The mobile Internet is the underlying contributor to the competitive environment of the entire Chinese smartphone industry. Xiaomi began its operations with the launch of its Android-based firmware MIUI (pronounced “Me You I”) in August 2010; a modified and hardcoded user interface, incorporating features from Apple’s IOS and Samsung’s TouchWizUI. As of 2018, Xiaomi is the world’s fourth largest smartphone manufacturer, and it has expanded its products and services to include a wider range of consumer electronics and a smart home device ecosystem. It is a company focused on developing new- generation smartphone software, and Xiaomi operated a successful mobile Internet business. Xiaomi has three core products: Mi Chat, MIUI and Xiaomi smartphones. This paper will use business management models from PEST, Porter’s five forces and SWOT to analyze the internal and external environment of Xiaomi. Finally, the paper evaluates whether Xiaomi has a strategic model of sustainable development, strategic flaws and recommend some suggestions to overcome them. -

Lamadrid Android

ANDROID FGSDFG FDDFGDF ANTITRUST Android antitrust investigation DOMINANT POSITION mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf okmsadf IT MARKET ANDROID FGSDFG FDDFGDF ANTITRUST Android antitrust investigation DOMINANT POSITION mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf okmsadf IT MARKET ANDROID FGSDFG FDDFGDF ANTITRUST Android antitrust investigation DOMINANT POSITION mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf okmsadf IT MARKET ANDROID THOUGHTS IN BRIEF: FGSDFG FDDFGDF(i) A quick overview of the facts (ii) Business considerations and ANTITRUSTbackground DOMINANT(iii)The POSITION Law : (I) Dominance mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf(iv)The Law: (II) Predatory okmsadf allegations IT MARKET(v) The Law: (III) Bundling allegations ANDROID FGSDFG THE FACTS FDDFGDF ANTITRUST DOMINANT POSITION mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf okmsadf IT MARKET • AndroidANDROID is an open source OS licensed on a royalty-free basis. Licensees remain free to do whatever they wish with the code (e.g. downloading,FGSDFG distributing or modifying –forking- it). • OEMs remain free to use Android with or without Google Apps (e.g. NokiaFDDFGDF X). • WhenANTITRUST OEMs wish to offer certain Google apps on top of Android they can enter into a MADA which requires them to (i) preload a minimum set ofDOMINANT apps (GMS); POSITION (ii) place Search widget and GooglePlay icons in a certain way; and (iii) use Google Search as default engine for the searchmokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf intent. okmsadf • OEMs (and users) remain at all times free to pre-install at any time any nonIT MARKET-Google app (including a non-Google App Store) = no Google walled garden (room for intra-ecosystem competition) ANDROID A MATTER OF DIFFERENT FGSDFG FDDFGDFBUSINESS MODELS ANTITRUST DOMINANT POSITION mokmdokamsdfkmasodmkfosakdmfosdkmf okmsadf IT MARKET EssentiallyANDROID 3 different business models for mobile operating systems (OSs): i. Apple’s vertically integrated model - Monetization via sales of devices. -

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Nexus S with Google running Android 2.3 "Gingerbread" Company / developer Google Inc., Open Handset Alliance [1] Programmed in C (core), C++ (some third-party libraries), Java (UI) Working state Current [2] Source model Free and open source software (3.0 is currently in closed development) Initial release 21 October 2008 Latest stable release Tablets: [3] 3.0.1 (Honeycomb) Phones: [3] 2.3.3 (Gingerbread) / 24 February 2011 [4] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, Power, x86 Kernel type Monolithic, modified Linux kernel Default user interface Graphical [5] License Apache 2.0, Linux kernel patches are under GPL v2 Official website [www.android.com www.android.com] Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications.[6] [7] Google Inc. purchased the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., in 2005.[8] Android's mobile operating system is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel. Google and other members of the Open Handset Alliance collaborated on Android's development and release.[9] [10] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[11] The Android operating system is the world's best-selling Smartphone platform.[12] [13] Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. There are currently over 150,000 apps available for Android.[14] [15] Android Market is the online app store run by Google, though apps can also be downloaded from third-party sites. -

Meego Smartphones and Operating System Find a New Life in Jolla Ltd

Jolla Ltd. Press Release July 7, 2012 Helsinki, Finland FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MeeGo Smartphones and Operating System Find a New Life in Jolla Ltd. Jolla Ltd. is an independent Finland based smartphone product company which continues the excellent work that Nokia started with MeeGo. The Jolla team is formed by directors and core professionals from Nokia's MeeGo N9 organisation, together with some of the best minds working on MeeGo in the communities. Jussi Hurmola, CEO Jolla Ltd.: "Nokia created something wonderful - the world's best smartphone product. It deserves to be continued, and we will do that together with all the bright and gifted people contributing to the MeeGo success story." Jolla Ltd. will design, develop and sell new MeeGo based smartphones. Together with international private investors and partners, a new smartphone using this MeeGo based OS will be revealed later this year. Jolla Ltd. has been developing a new smartphone product and the OS since the end of 2011. The OS has evolved from MeeGo OS using Mer Core and Qt with Jolla technology including its own brand new UI. The Jolla team consists of a substantial number of MeeGo's core engineers and directors, and is aggressively hiring the top MeeGo and Linux talent to contribute to the next generation smartphone production. Company is headquartered in Helsinki, Finland and has an R&D office in Tampere, Finland. Sincerely, Jolla Ltd. Dr. Antti Saarnio - Chairman & Finance Mr. Jussi Hurmola - CEO Mr. Sami Pienimäki - VP, Sales & Business Development Mr. Stefano Mosconi - CIO Mr. Marc Dillon - COO Further inquiries: [email protected] Jolla Ltd. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

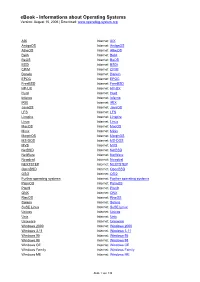

Ebook - Informations About Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download

eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org AIX Internet: AIX AmigaOS Internet: AmigaOS AtheOS Internet: AtheOS BeIA Internet: BeIA BeOS Internet: BeOS BSDi Internet: BSDi CP/M Internet: CP/M Darwin Internet: Darwin EPOC Internet: EPOC FreeBSD Internet: FreeBSD HP-UX Internet: HP-UX Hurd Internet: Hurd Inferno Internet: Inferno IRIX Internet: IRIX JavaOS Internet: JavaOS LFS Internet: LFS Linspire Internet: Linspire Linux Internet: Linux MacOS Internet: MacOS Minix Internet: Minix MorphOS Internet: MorphOS MS-DOS Internet: MS-DOS MVS Internet: MVS NetBSD Internet: NetBSD NetWare Internet: NetWare Newdeal Internet: Newdeal NEXTSTEP Internet: NEXTSTEP OpenBSD Internet: OpenBSD OS/2 Internet: OS/2 Further operating systems Internet: Further operating systems PalmOS Internet: PalmOS Plan9 Internet: Plan9 QNX Internet: QNX RiscOS Internet: RiscOS Solaris Internet: Solaris SuSE Linux Internet: SuSE Linux Unicos Internet: Unicos Unix Internet: Unix Unixware Internet: Unixware Windows 2000 Internet: Windows 2000 Windows 3.11 Internet: Windows 3.11 Windows 95 Internet: Windows 95 Windows 98 Internet: Windows 98 Windows CE Internet: Windows CE Windows Family Internet: Windows Family Windows ME Internet: Windows ME Seite 1 von 138 eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org Windows NT 3.1 Internet: Windows NT 3.1 Windows NT 4.0 Internet: Windows NT 4.0 Windows Server 2003 Internet: Windows Server 2003 Windows Vista Internet: Windows Vista Windows XP Internet: Windows XP Apple - Company Internet: Apple - Company AT&T - Company Internet: AT&T - Company Be Inc. - Company Internet: Be Inc. - Company BSD Family Internet: BSD Family Cray Inc. -

Test Coverage Guide

TEST COVERAGE GUIDE Test Coverage Guide A Blueprint for Strategic Mobile & Web Testing SUMMER 2021 1 www.perfecto.io TEST COVERAGE GUIDE ‘WHAT SHOULD I BE TESTING RIGHT NOW?’ Our customers often come to Perfecto testing experts with a few crucial questions: What combination of devices, browsers, and operating systems should we be testing against right now? What updates should we be planning for in the future? This guide provides data to help you answer those questions. Because no single data source tells the full story, we’ve combined exclusive Perfecto data and global mobile market usage data to provide a benchmark of devices, web browsers, and user conditions to test on — so you can make strategic decisions about test coverage across mobile and web applications. CONTENTS 3 Putting Coverage Data Into Practice MOBILE RECOMMENDATIONS 6 Market Share by Country 8 Device Index by Country 18 Mobile Release Calendar WEB & OS RECOMMENDATIONS 20 Market Share by Country 21 Browser Index by Desktop OS 22 Web Release Calendar 23 About Perfecto 2 www.perfecto.io TEST COVERAGE GUIDE DATA INTO PRACTICE How can the coverage data be applied to real-world executions? Here are five considerations when assessing size, capacity, and the right platform coverage in a mobile test lab. Optimize Your Lab Configuration Balance Data & Analysis With Risk Combine data in this guide with your own Bundle in test data parameters (like number of tests, analysis and risk assessment to decide whether test duration, and required execution time). These to start testing with the Essential, Enhanced, or parameters provide the actual time a full- cycle or Extended mobile coverage buckets. -

AGIS SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT § LLC, § Case No

Case 2:19-cv-00361-JRG Document 1 Filed 11/04/19 Page 1 of 70 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION § AGIS SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT § LLC, § Case No. § Plaintiff, § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED § v. § § GOOGLE LLC, § § Defendant. § § PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff, AGIS Software Development LLC (“AGIS Software” or “Plaintiff”) files this original Complaint against Defendant Google LLC (“Defendant” or “Google”) for patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271 and alleges as follows: THE PARTIES 1. Plaintiff AGIS Software is a limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of Texas, and maintains its principal place of business at 100 W. Houston Street, Marshall, Texas 75670. AGIS Software is the owner of all right, title, and interest in and to U.S. Patent Nos. 8,213,970, 9,408,055, 9,445,251, 9,467,838, 9,749,829, and 9,820,123 (the “Patents-in-Suit”). 2. Defendant Google is a Delaware corporation and maintains its principal place of business at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California 94043, and may be served with process via its registered agent, Corporation Service Company at 251 Little Falls Drive, Wilmington, DE 19808. Upon information and belief, Google does business in Texas, directly or through intermediaries, and offers its products and/or services, including those accused herein Case 2:19-cv-00361-JRG Document 1 Filed 11/04/19 Page 2 of 70 PageID #: 2 of infringement, to customers and potential customers located in Texas, including in the judicial Eastern District of Texas. -

Android-X86 Project Marshmallow Porting

Android-x86 Project Marshmallow Porting https://drive.google.com/open?id=1mND8K-AXbMMl8- wOTe75NOpM0xOcJbVy8UorryHOWsY 黃志偉 [email protected] 2015/11/28 http://www.android-x86.org Agenda ●Introduction: what, why, how? ●History and milestones ●Current status ●Porting procedure ●Develop android-x86 ●Future plans android-x86.org About Me ●A free software and open source amateur and promoter from Taiwan ■ CLDP / CLE ■ GNU Gatekeeper ■ Android-x86 Open Source Project ●https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cwhuang android-x86.org Introduction ●What's Android-x86? ●Why needs Android-x86? ●How can we do it? android-x86.org What's Android-x86 ? ●An open source project aimed to provide a complete solution for Android on x86 devices ●Android BSP (Board support Package) for x86 platform ●At first we use ASUS Eee PC and Virtualbox as the reference platform. ●Some vendors donate tablets, like Tegatech Tegav2, 4tiitoo AG WeTab and AMD android-x86.org Why needs Android-x86? ●Android is an open source operating-system originally designed for arm platform ●It's open source, we can port it to other platforms, like mips, PowerPC and x86 ●AOSP officially supports x86 now ● AOSP doesn’t have specific hardware components ● Still a lot of work to do to make it run on a real device android-x86.org But what are the benefits? ●Understanding Android porting process ●The x86 platform is widely available ●A test platform much faster than SDK emulator ●Android-x86 on vbox / vmware ●Suitable for tablet apps android-x86.org Android architecture android-x86.org How to do that? ●Toolchains – already in AOSP, but old.. -

Sailfish OS Interview Questions and Answers Guide

Sailfish OS Interview Questions And Answers Guide. Global Guideline. https://www.globalguideline.com/ Sailfish OS Interview Questions And Answers Global Guideline . COM Sailfish OS Job Interview Preparation Guide. Question # 1 Tell us what you know about Sailfish OS? Answer:- Sailfish is a Linux-based mobile operating system developed by Jolla in cooperation with the Mer project and supported by the Sailfish Alliance. It is to be used in upcoming smartphones by Jolla and other licencees. Although it is primarily targeted at mobile phones, it is also intended to support other categories of devices. Read More Answers. Question # 2 Explain Sailfish OS Components? Answer:- Jolla has revealed its plans to use the following technologies in Sailfish OS: The Mer software distribution core A custom built user interface HTML5 QML and Qt Read More Answers. Question # 3 Do you know about Sailfish OS software availability? Answer:- Sailfish will be able to run most applications that were originally developed for MeeGo and Android, in addition to native Sailfish applications. This will give it a large catalogue of available apps on launch. Considering upon Jolla's declarations that Sailfish OS is be able to use software from following platforms Sailfish (natively created + ported like from Qt, Symbian, MeeGo - developers have reported that porting a Qt written software with Sailfish SDK takes a few hours only) Android applications are directly running in Sailfish OS. They are compatible as they are in third-party Android stores, with no needed modification (in most cases). MeeGo (because of backward compatibility thanks to MeeGo code legacy included in the Mer core) Unix and Linux (as Sailfish is Linux then using such a software is possible, especially RPM packages, either in terminal/console mode or with limitations implying from using Sailfish UI, if not ported and adjusted) HTML5 Read More Answers.