Efficient Market Theory: Let the Punishment Fit the Crime* Louis Lowenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: ___________Gilbert’s Hill__________________________ Other names/site number: _________Appel Farm_____________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: N/A___________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _1362 Barnard Road/Route 12_____________________________ City or town: Woodstock/Pomfret State: Vermont County: Windsor Not For Publication: Vicinity: n/a n/a ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

The Mecca of Value Investing

The mecca of Value Investing Subject: The mecca of Value Invesng From: CSH Investments <[email protected]> Date: 6/18/2019, 1:44 PM To: Randy <[email protected]> View this email in your browser Some of you know I'm a big believer in lifetime learning. It wasn't always the case. My early academic years were less than stellar. But I caught on fairly quickly and made do. By my late 20's I knew I wanted to be in finance. I had studied finance and economics in college but it didn't really grab me. Looking back partly it was me but also it was the way it was taught. Stodgy old theories that really didn't make any sense to me. The Efficient Market Theory for instance. EMT says basically that the markets are fully efficient. That stocks are perfectly priced therefore there aren't any bargains. You have absolutely nothing to gain from fundamental analysis and if you do it you are wasting your time. Yeah I thought but I knew there were guys who did exactly that. They did 1 of 5 6/18/2019, 4:48 PM The mecca of Value Investing their own research and found things that were mispriced. Most of them were quite wealthy. If the market is perfectly efficient as you say then how can they do it? And almost every theory had a list of assumptions you had to make. Here's one I love, every investor has the same information. Well, let's just be logical every investor doesn't have the same information and even if they did they would interpret differently. -

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After Receiving His Ph.D

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1959, Frank Knight joined the mathematics department of the University of Minnesota. Frank liked Minnesota; the cold weather proved to be no difficulty for him since he climbed in the Rocky Mountains even in the winter time. But there was one problem: airborne flour dust, an unpleasant output of the large companies in Minneapolis milling spring wheat from the farms of Minnesota. Frank discovered that he was allergic to flour dust and decided that he would try to move to another location. His research was already recognized as important. His first four papers were published in the Illinois Journal of Mathematics and the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. At that time, J.L. Doob was one of the editors of the Illinois Journal and attracted some of the best papers in probability theory to the journal including some of Frank's. He was hired by Illinois and served on its faculty from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. After his retirement, Frank continued to be active in his research, perhaps even more active since he no longer had to grade papers and carefully prepare his classroom lectures as he had always done before. In 1994, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For many years, this did not slow him down mathematically. He also kept physically active. At first, his health declined slowly but, in recent years, more rapidly. He died on March 19, 2007. Frank Knight's contributions to probability theory are numerous and often strikingly creative. -

The Intelligent Investor

THE INTELLIGENT INVESTOR A BOOK OF PRACTICAL COUNSEL REVISED EDITION BENJAMIN GRAHAM Updated with New Commentary by Jason Zweig An e-book excerpt from To E.M.G. Through chances various, through all vicissitudes, we make our way.... Aeneid Contents Epigraph iii Preface to the Fourth Edition, by Warren E. Buffett viii ANote About Benjamin Graham, by Jason Zweigx Introduction: What This Book Expects to Accomplish 1 COMMENTARY ON THE INTRODUCTION 12 1. Investment versus Speculation: Results to Be Expected by the Intelligent Investor 18 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 1 35 2. The Investor and Inflation 47 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 2 58 3. A Century of Stock-Market History: The Level of Stock Prices in Early 1972 65 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 3 80 4. General Portfolio Policy: The Defensive Investor 88 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 4 101 5. The Defensive Investor and Common Stocks 112 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 5 124 6. Portfolio Policy for the Enterprising Investor: Negative Approach 133 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 6 145 7. Portfolio Policy for the Enterprising Investor: The Positive Side 155 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 7 179 8. The Investor and Market Fluctuations 188 iv v Contents COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 8 213 9. Investing in Investment Funds 226 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 9 242 10. The Investor and His Advisers 257 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 10 272 11. Security Analysis for the Lay Investor: General Approach 280 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 11 302 12. Things to Consider About Per-Share Earnings 310 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 12 322 13. A Comparison of Four Listed Companies 330 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 13 339 14. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

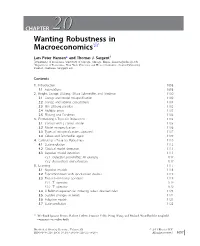

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

Benjamin Graham: the Father of Financial Analysis

BENJAMIN GRAHAM THE FATHER OF FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Irving Kahn, C.F.A. and Robert D. M£lne, G.F.A. Occasional Paper Number 5 THE FINANCIAL ANALYSTS RESEARCH FOUNDATION Copyright © 1977 by The Financial Analysts Research Foundation Charlottesville, Virginia 10-digit ISBN: 1-934667-05-6 13-digit ISBN: 978-1-934667-05-7 CONTENTS Dedication • VIlI About the Authors • IX 1. Biographical Sketch of Benjamin Graham, Financial Analyst 1 II. Some Reflections on Ben Graham's Personality 31 III. An Hour with Mr. Graham, March 1976 33 IV. Benjamin Graham as a Portfolio Manager 42 V. Quotations from Benjamin Graham 47 VI. Selected Bibliography 49 ******* The authors wish to thank The Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts staff, including Mary Davis Shelton and Ralph F. MacDonald, III, in preparing this manuscript for publication. v THE FINANCIAL ANALYSTS RESEARCH FOUNDATION AND ITS PUBLICATIONS 1. The Financial Analysts Research Foundation is an autonomous charitable foundation, as defined by Section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. The Foundation seeks to improve the professional performance of financial analysts by fostering education, by stimulating the development of financial analysis through high quality research, and by facilitating the dissemination of such research to users and to the public. More specifically, the purposes and obligations of the Foundation are to commission basic studies (1) with respect to investment securities analysis, investment management, financial analysis, securities markets and closely related areas that are not presently or adequately covered by the available literature, (2) that are directed toward the practical needs of the financial analyst and the portfolio manager, and (3) that are of some enduring value. -

ECONOMIC MAN Vs HUMANITY Lyrics

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS PRESENTS . ECONOMIC MAN vs. HUMANITY: A PUPPET RAP BATTLE STARRING: Storyline and lyrics by Simon Panrucker, Emma Powell and Kate Raworth Key concepts and quotes are drawn from Chapter 3 of Doughnut Economics. * VOICE OVER And so this concept of rational economic man is a cornerstone of economic theory and provides the foundation for modelling the interaction of consumers and firms. The next module will start tomorrow. If you have any questions, please visit your local Knowledge Bank. POTATO Hello? BRASH Hello? FACTS Shall we go to the knowledge bank? BRASH Yeah that didn’t make any sense! POTATO See you outside. They pop up outside. BRASH Let’s go! They go to The Knowledge Bank. PROF Welcome to The Knowledge Ba… oh, it’s you lot. What is it this time? FACTS The model of rational economic man PROF Look, it's just a starting point for building on POTATO Well from the start, something doesn’t sit right with me BRASH We’ve got questions! PROF sighs. PROF Ok, let me go through it again . THE RAP BEGINS PROF Listen, it’s quite simple... At the heart of economics is a model of man A simple distillation of a complicated animal Man is solitary, competing alone, Calculator in head, money in hand and no Relenting, his hunger for more is unending, Ego in heart, nature’s at his will for bending POTATO But that’s not me, it can’t be true! There’s much more to all the things humans say and do! BRASH It’s rubbish! FACTS Well, it is a useful tool For economists to think our reality through It’s said that all models are wrong but some -

A Business Lawyer's Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read

585 A Business Lawyer’s Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read Robert C. Illig Introduction There exists today in America’s libraries and bookstores a superb if underappreciated resource for those interested in teaching or learning about business law. Academic historians and contemporary financial journalists have amassed a huge and varied collection of books that tell the story of how, why and for whom our modern business world operates. For those not currently on the front line of legal practice, these books offer a quick and meaningful way in. They help the reader obtain something not included in the typical three-year tour of the law school classroom—a sense of the context of our practice. Although the typical law school curriculum places an appropriately heavy emphasis on theory and doctrine, the importance of a solid grounding in context should not be underestimated. The best business lawyers provide not only legal analysis and deal execution. We offer wisdom and counsel. When we cast ourselves in the role of technocrats, as Ronald Gilson would have us do, we allow our advice to be defined downward and ultimately commoditized.1 Yet the best of us strive to be much more than legal engineers, and our advice much more than a mere commodity. When we master context, we rise to the level of counselors—purveyors of judgment, caution and insight. The question, then, for young attorneys or those who lack experience in a particular field is how best to attain the prudence and judgment that are the promise of our profession. For some, insight is gained through youthful immersion in a family business or other enterprise or experience. -

A Century of Ideas

COLUMBIA BUSINESS SCHOOL A CENTURY OF IDEAS EDITED BY BRIAN THOMAS COLUMBIA BUSINESS SCHOOL Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright © 2016 Columbia Business School All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Thomas, Brian, editor. | Columbia University. Graduate School of Business. Title: Columbia Business School : a century of ideas / edited by Brian Thomas. Description: New York City : Columbia University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016014665| ISBN 9780231174022 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231540841 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Columbia University. Graduate School of Business—History. Classification: LCC HF1134.C759 C65 2016 | DDC 658.0071/17471—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016014665 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Foreword vii 1 Finance and Economics 1 2 Value Investing 29 3 Management 55 4 Marketing 81 5 Decision, Risk, and Operations 107 6 Accounting 143 7 Entrepreneurship 175 vi CONTENTS 8 International Business 197 9 Social Enterprise 224 Current Full-Time Faculty at Columbia Business School 243 Index 247 foreword Ideas with Impact Glenn Hubbard, Dean and Russell L. Carson Professor of Finance and Economics Columbia Business School’s first Centennial offers a chance for reflection about past success, current challenges, and future opportunities. Our hundred years in business education have been in a time of enormous growth in interest in university-based business education. Sixty-one students enrolled in 1916. -

1290 GAMCO Small/Mid Cap Value Fund September 2017

Fund Fact Sheet 1290 GAMCO Small/Mid Cap Value Fund September 2017 Investment Philosophy/Process Search for companies with Utilize Columbia University Seek to buy reasonably-priced attractive Private Market Value, professors Benjamin Graham and strong franchises within or PMV (the price an informed and David Dodd's "Margin of GAMCO's circle of competence industrialist would pay for the Safety" concept – by investing entire company) and a catalyst, in securities with a material an event to surface the value of difference between their market the company and estimated intrinsic values Fund Facts A small- and mid-capitalization strategy from well-known stock picker Mario Gabelli Symbols & CUSIPs: Class A TNVAX 68246A 108 Class I TNVIX 68246A 306 Build Fund From the Bottom Up Class R TNVRX 68246A 405 Min. Initial Investment: $1,000 for A Shares* Individual holdings weighting reects optimal risk/reward level Inception Date: November 12, 2014 Portfolio Dividends: Annually Adviser: 1290 Asset Managers Subadviser: GAMCO Investors Identify event to surface the estimated Identify Catalysts value and determine "Margin of Safety" * Refer to Prospectus for other Fund minimums. Total What Expense Ratios Expense Ratio You Pay** Determine PMV (the price an informed Class A 4.38% 1.25% Determine Value industrialist would pay for the entire company) Class I 4.09% 1.00% Class R 4.65% 1.50% ** What You Pay reflects the Adviser's decision to Select from a global universe of over 2,000 contractually limit expenses through April 30, 2018. Research Universe Please see the prospectus for additional information. companies using proprietary research Mario J. -

Why Financial Appearances Might Matter: an Explanation for "Dirty Pooling" and Some Other Types of Financial Cosmetics

ARTICLE: WHY FINANCIAL APPEARANCES MIGHT MATTER: AN EXPLANATION FOR "DIRTY POOLING" AND SOME OTHER TYPES OF FINANCIAL COSMETICS 1997 Reporter 22 Del. J. Corp. L. 141 Length: 19623 words Author: By Claire A. Hill * * Assistant Professor of Law, George Mason University School of Law. This article was written in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctor of the Science of Law in the Faculty of Law, Columbia University. I wish to acknowledge helpful comments made by the participants at the Law and Economics Workshop at George Mason, particularly, Peg Brinig, Frank Buckley, Lloyd Cohen, L. Bruce Johnsen, Erin O'Hara, and Peter Letsou, Bill Lash, and participants at the Canadian Law and Economics Association Conference, particularly John Palmer. I also wish to acknowledge helpful conversations with Bernie Black, Victor Goldberg, and David Gordon. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Sujatha Bagal and Scott Faga, both George Mason University School of Law Class of 1997. LexisNexis Summary … "What's more important, economic substance or accounting appearance? Banks are voting for appearance, hands down." … The information cost structure which gave rise to the mispricing might very well continue; thus, an arbitrageur's investment might never pay off. … Debt, too, can be "managed" using financial statement beautification techniques. … No matter how visible, the effects of financial statement beautification techniques, whether relating to debt or earnings, are not costlessly translatable. … By contrast, in a pooling, the asset's basis has stayed the same, resulting in higher gain on sale. … Because I am trying to explain financial statement beautification, my analysis considers only debt-equity swaps done for cosmetic reasons.