C H a P T E R 8 -: 261

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Gobar Times Green School Awards Conferred to Sikkim Schools by New Delhi Based Centre for Science & Environment

NATIONAL GREEN CORPS SIKKIM An Activity Report on Student’s Environment Movement July 2012 Forests, Environment & Wildlife Management Department Ministry of Environment & Forests Government of Sikkim Government of India NATIONAL GREEN CORPS (NGC) SIKKIM STATE An Activity Report on Student’s Environment Movement July 2012 Prepared and Submitted by ENVIS CENTER SIKKIM On Status of Environment & Related Issues Forests, Environment & Wildlife Management Department Government of Sikkim Table of Contents Foreword 1 Preface 2 Unity in Diversity: Participation at National Events Sikkim NGC at the First National Meet at Hyderabad 4 Paryavaran Mitra National Event at Goa 6 Visit to Sikkim Express – Biodiversity Special Train at Siliguri 6 State Government’s Environmental Initiative at Schools Mission 2015: 100 percent Environment Conscious Citizen in Sikkim by 2015 8 Green Schools Programme – Sikkim State 9 Green Teacher’s Training 10 Environment Kits to School Eco‐Clubs 11 State Green Schools Awards – Chief Minister’s Green School Rolling Trophy 12 Celebrating Environment Calendar Days with Meaningful Commitments Environment Calendar for Sikkim Schools 19 World Forestry Day 20 Earth Day 22 International Biodiversity Day 26 Saving Lake Gyam Tsona – Sikkim’s Ocean in the Sky 28 World Environment Day 30 Paryavaran Mitra Oath 32 State Green Mission and 36 Ten Minutes to Earth – Creating Carbon Sink 37 Ozone Day 38 World Wildlife Week 39 Contd… Eco‐Club Activities –Environment Management System under the Green Schools Programme 41 Auditing Water Consumption 42 Rain Water Harvesting 43 Reusing Waste Water 44 Sensitization on Ground Water Recharge 45 Hugging the Oldest Tree 46 Making of a Botanical Garden 47 Preparation of Biodiversity Register 49 Wall Magazines & Green Boards 50 Learning through Nature 51 Energy Conservation 52 Cleanliness drive 53 Solid Waste Management 54 Vermin Composting 56 Learning to Reuse Paper and Plastic Waste 58 Paryavaran Mitra Programme – A report of Yuksom Sr. -

Sub-National Jurisdictional Redd+ Program for Sikkim, India

SUB-NATIONAL JURISDICTIONAL REDD+ PROGRAM FOR SIKKIM, INDIA Prepared by Sikkim Forest, Environment & Wildlife Management Department Supported by the USAID-funded Partnership for Land Use Science (Forest-PLUS) Program June 2017 Version 1.2 Sub-National Jurisdictional REDD+ Program for Sikkim, India 4.1 Table of Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 9 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 12 1.1 Background and overview..................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Objective ..................................................................................................................................... 17 1.3 Project Executing Entity .............................................................................................................. 18 2. Scope of the Program .................................................................................................................. -

Naresh Agarwal's Curriculum Vitae

N A R E S H K U M A R A G A R W A L July 16, 2021 Associate Professor / Director, Information Science & Technology Concentration President-elect, Association for Information Science & Technology School of Library and Information Science College of Organizational, Computational, & Information Sciences Simmons University, 300 The Fenway, Boston MA 02115 (617) 521 2836, [email protected], twitter: @nareshag simmons.edu/academics/faculty/naresh-agarwal web.simmons.edu/~agarwal, projectonenessworld.com EDUCATION 2010 Ph.D., Department of Information Systems School of Computing, National University of Singapore Dissertation Information Seeking Behavior and Context: Theoretical Frameworks and an Empirical Study of Source Use 1999 B.A.Sc. (Computer Engineering) Honors Nanyang Technological University, Singapore EMPLOYMENT 2009 - School of Library and Information Science, Simmons University Associate Professor, 2015 – Assistant Professor, 2009-2015 Research Areas Information Behavior, Knowledge Management Teaching Areas Technology for Information Professionals, Theories of Information Science, Knowledge Management, Web Dev. & Information Architecture, Evaluation of Information Services Format Face-to-face, online, blended 2004-2007 Department of Information Systems, School of Computing National University of Singapore Research Assistant, 2004-2006 Teaching Assistant, 2007 1 1997-2004 Software Industry experience, Singapore GDC Technology Ltd, Digital Cinema Technology, 2003-2004 HeliXense Pte Ltd, BioInformatics, 2002 Innova Solutions, Customer Relationship/Telecom, 2001-2002 MediaRing Ltd, Voice-over-IP, 1999-2001 Hewlett-Packard, Telecom, Internship, 1997 PUBLICATIONS Refereed Journal Articles J1. Agarwal, N. K., Mitiku, T., & Lu, W.* (accepted with revisions). Disconnectedness in a connected world: Why people ignore messages and calls. Aslib Journal of Information Management. Accepted with revisions on July 16, 2021. -

Stories of the Lepcha

( (#&'#( $ &&(*'&#!#"('( " - &&- (( )!((") !"(#(&%)&!"('#&( &# #(#&# #'#$- "( ) (-#&('"# "' "*&'(-#"# #-/-"- 7568 &((#)(#&'$1&" (- ,.# 3.".."1),%#(."#-."-#-"-().*,0#)/-&3(-/'#.. ), !,(#-().#(!-/'#..-*,.) (#./, ),(3).",!,; &-),.# 3.".."."-#-"-(1,#..(3';(3"&*.". "0,#0 #('3,-,"1),%(."*,*,.#)() ."."-#-#.-& "-( %()1&!; (#.#)(8 ,.# 3.".&&#( ),'.#)(-)/,-(&#.,./, /-,#(#.#(."."-#-; #!(./,) (#. &&- (( 156558=86 ## "#+ !"(' (HFFL81"( .,0&&.)#%%#'(-.(!&.),),."-.),#-) ." *"8 ,,#01#."-&#')((.#)(-.)!(,)/-*)*&; "0'&)- ,#(-1")*,'#..'(#(-#,@---(#(.#'31"(,),#(!."#, -.),#-;"3&&)1'.)*,)1&,)/(1#.",),,8',( ().*8+/-.#)(#(!8&,# 3#(!8(#(-,.#(!'3(--,-,",#(.) ."#,�-;"3#(0#.'.)�#(."#,")'-8.)-",."#, ))($)#( ."#, '#&3&# ; '."(% /&(!,. /&.)." *")''/(#.#-#(#%%#'(-.(!& ),."#,--#-.(;#,-.8'3."(%-.) /((/,#**8 ),-/!!-.#(! ,), *"-.),#-81"#"&'.)."#,(& 1,(#.&#(!().", '#&3'',-1")"&*'#(.",&3-.!-) ,-,"; "'',-) .#.#4(-) -.8#(&/#(!,-#(.8."/* *" 1,)*((.,/-.#(!1#."."#,(,,.#0-( '#(..)."';" .,/-.(!(,)-#.3-")1(3"/(!,-.,#%,-1 *"((4#(! *" #-, &.#(&')-.0,3"*.,) ."#-."-#-;" (#!()/- *",#& --)#.#)(#(-.(!&8/(,."&,-"#*) $), 3(!-)(!'-(!= )(!8(3)/."&,-),$# *"(4/% *"8*,)0#0&/& #(-#!".#(.) *""#-.),38/-.)'-(&#.,./,; ((!.)% �#( +."")') ",* *"8"#-1# ")(8 ,).",' *"(."#,2.( '#&3;"3,'3#%%#' '#&3(8 -1&&-")'8*,)0#').#)(&-"&.,/,#(!&)(!*,#)-13 ,)' /-.,&#; &-)**,#.." ,#(-"#*- '.(!.)%@-/&./,&"/8 "())%-81",8()/,!3)1(,'(",-.8#%%#'@-,.#0 (#(+/#,#(!'#(-'. ),/&./,&0(.-()(0,-.#)(; ,+/(. 0#-#.),.)"(8."$)/,(&#-.#./&8#-%()1&! ),",,.#&-( ))%-( ),0#-#(!')(."#!!,*#./,) #%%#'-*)&#.#-; -

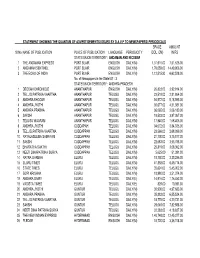

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00 -

Media Ownership and News Coverage of International Conflict

Media Ownership and News Coverage of International Conflict Matthew Baum Yuri Zhukov Harvard Kennedy School University of Michigan matthew [email protected] [email protected] How do differences in ownership of media enterprises shape news coverage of international conflict? We examine this relationship using a new dataset of 591,532 articles on US-led multinational military opera- tions in Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan and Kosovo, published by 2,505 newspapers in 116 countries. We find that ownership chains exert a homogenizing effect on the content of newspapers’ coverage of foreign pol- icy, resulting in coverage across co-owned papers that is more similar in scope (what they cover), focus (how much “hard” relative to “soft” news they offer), and diversity (the breadth of topics they include in their coverage of a given issue) relative to coverage across papers that are not co-owned. However, we also find that competitive market pressures can mitigate these homogenizing effects, and incentivize co-owned outlets to differentiate their coverage. Restrictions on press freedom have the opposite impact, increasing the similarity of coverage within ownership chains. February 27, 2018 What determines the information the press reports about war? This question has long concerned polit- ical communication scholars (Hallin 1989, Entman 2004). Yet it is equally important to our understanding of international conflict. Prevailing international relations theories that take domestic politics into account (e.g., Fearon 1994, 1995, Lake and Rothschild 1996, Schultz 2001) rest on the proposition that the efficient flow of information – between political leaders and their domestic audiences, as well as between states involved in disputes – can mitigate the prevalence of war, either by raising the expected domestic political costs of war or by reducing the likelihood of information failure.1 Yet models of domestic politics have long challenged the possibility of a perfectly informed world (Downs 1957: 213). -

Ads2publish.Com Advantages!

Book Newspaper Classified Ads Online! Now you don't have to physically travel to the newspaper/ representave office to release an ad. Nor you have to manually write ad messages on forms. Do all this and more at Ads2Publish.com, from the comforts of your home, office or even while you are traveling. What's more, you can choose from a number of publicaons that suit your target audience profile, select the category that suits your classified ad, and make payment through a secure gateway. Go ahead, experience the easy, effortless way to publish an ad, now! Ads2publish is India's Online Newspaper Classified Ad Booking Service. You can book Classified or Display Ads for all leading Newspapers in India. Book your Newspaper Ad instantly in 3 easy steps Ÿ Choose Ad Category, Newspaper, Edion, Date Ÿ Compose Your Ad and Ÿ Make Payment Book your Matrimonial, Property, Vehicle, Business, Educaon, Recruitment, Travel and other categories classified Ads. We accepts both online and offline payments. Ads2Publish.com Advantages! Wherever - Easy & efficient way to book ad from anywhere on earth Whenever - Book your ad anyme of the day or night and pay securely Whatever - From all available categories to almost all publicaons Book Ads online for the following categories in all leading newspapers Matrimonial Recruitment Property Sale Name Change Lost Found Vehicles Property Rental Astrology Business Computers Classified Educaon Remembrance Personal Personal Obituary Announcement Message Retail Services Travel Book Matrimonial Classified, Property Classified, Rental Classified, -

Lok Sabha Q No. 2209

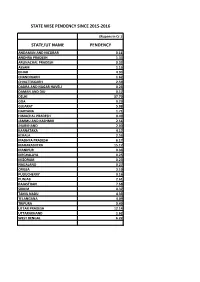

STATE WISE PENDENCY SINCE 2015-2016 PENDENCY (Rupees in Cr.) STATE/UT NAME 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 2018-2019 2019-2020 2020-2021 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 0.00 0.02 0.01 0.04 0.02 0.02 ANDHRA PRADESH 0.05 0.18 0.18 0.36 0.21 0.35 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 0.01 0.05 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.06 ASSAM 0.04 0.13 0.20 0.33 0.18 0.28 BIHAR 0.12 1.07 1.01 1.21 0.65 0.87 CHANDIGARH 0.07 0.31 0.32 0.39 0.28 0.25 CHHATTISGARH 0.08 0.42 0.28 0.78 0.48 0.55 DADRA AND NAGAR HAVELI 0.01 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.03 0.06 DAMAN AND DIU 0.00 0.03 0.02 0.05 0.03 0.04 DELHI 3.60 9.92 5.31 8.58 6.61 3.77 GOA 0.03 0.07 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.05 GUJARAT 0.27 0.99 0.99 1.20 0.64 0.99 HARYANA 0.08 0.44 0.33 0.30 0.24 0.31 HIMACHAL PRADESH 0.03 0.09 0.06 0.15 0.07 0.09 JAMMU AND KASHMIR 0.09 0.29 0.33 0.69 0.49 0.61 JHARKHAND 0.05 0.34 0.35 0.50 0.33 0.43 KARNATAKA 0.34 0.95 0.61 0.96 0.63 0.69 KERALA 0.07 0.46 0.43 0.56 0.46 0.58 MADHYA PRADESH 0.18 1.27 0.76 1.48 0.90 1.57 MAHARASHTRA 1.04 3.10 2.20 3.72 2.49 2.62 MANIPUR 0.01 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.07 0.10 MEGHALAYA 0.01 0.04 0.04 0.07 0.04 0.06 MIZORAM 0.01 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.05 NAGALAND 0.01 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.05 0.03 ORISSA 0.12 0.48 0.44 0.99 0.42 0.74 PUDUCHERRY 0.00 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.02 0.02 PUNJAB 0.12 0.45 0.43 0.75 0.39 0.46 RAJASTHAN 0.27 2.25 0.85 1.75 0.93 1.53 SIKKIM 0.02 0.06 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.10 TAMIL NADU 0.20 1.01 0.78 1.11 0.70 0.52 TELANGANA 0.25 0.75 0.72 0.90 0.77 0.70 TRIPURA 0.01 0.06 0.09 0.11 0.09 0.13 UTTAR PRADESH 0.43 2.39 1.52 3.85 1.56 2.40 UTTARAKHAND 0.07 0.31 0.23 0.40 0.26 0.35 WEST BENGAL 0.37 1.69 1.07 1.69 -

Hazards, Infrastructure, and Indigenous Politics in Sikkim, India

PRECARITY AND POSSIBILITY AT THE MARGINS: HAZARDS, INFRASTRUCTURE, AND INDIGENOUS POLITICS IN SIKKIM, INDIA Mabel Denzin Gergan A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geography. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Sara Smith Arturo Escobar Elizabeth Olson Gabriela Valdivia Scott Kirsch © 2016 Mabel Denzin Gergan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Mabel Denzin Gergan: Precarity and Possibility at the Margins: Hazards, Infrastructure, and Indigenous Politics in Sikkim, India. (Under the direction of: Dr. Sara Smith) This research aims to understand the intimate linkages between hazards, infrastructure, and indigenous politics in the context of anti-dam activism and a 6.9 magnitude earthquake in the Eastern Himalayan state of Sikkim, India. The Indian Himalayan Region, a climate change hotspot, is witnessing a massive surge in large scale infrastructural development alongside an increase in the frequency and intensity of natural hazard events. Earthquakes and landslides near hydropower project sites, along with incidents of shamanic possession by angered mountain deities, raised serious doubts about the viability of hydropower projects for both local communities and regional technocrats. I take a materialist and postcolonial approach to examine how state apathy combined with the visceral quality of ecological precarity, has prompted solidarity between disparate groups and demands for policies and projects sensitive to the region’s cultural and geo-physical particularities. I also foreground the experiences of indigenous youth to demonstrate how environmental vulnerability has a direct bearing on young people’s lives, labor, and politics. -

Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question No.870

STATE WISE PENDENCY SINCE 2015-2016 (Rupees in Cr.) STATE/UT NAME PENDENCY ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 0.11 ANDHRA PRADESH 1.33 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 0.32 ASSAM 1.15 BIHAR 4.93 CHANDIGARH 1.62 CHHATTISGARH 2.59 DADRA AND NAGAR HAVELI 0.23 DAMAN AND DIU 0.17 DELHI 37.79 GOA 0.29 GUJARAT 5.08 HARYANA 1.71 HIMACHAL PRADESH 0.49 JAMMU AND KASHMIR 2.51 JHARKHAND 2.00 KARNATAKA 4.17 KERALA 2.56 MADHYA PRADESH 6.17 MAHARASHTRA 15.17 MANIPUR 0.33 MEGHALAYA 0.25 MIZORAM 0.23 NAGALAND 0.27 ORISSA 3.19 PUDUCHERRY 0.16 PUNJAB 2.61 RAJASTHAN 7.58 SIKKIM 0.37 TAMIL NADU 4.33 TELANGANA 4.09 TRIPURA 0.49 UTTAR PRADESH 12.14 UTTARAKHAND 1.62 WEST BENGAL 6.22 STATE WISE & NEWSPAPER WISE PENDENCY SINCE 2015-2016 PENDENCY STATE/UT NAME NEWSPAPER NAME PERIODICITY (Rupees in Cr.) ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ARTHIK LIPI DAILY(M) 0.01 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR THE ECHO OF INDIA DAILY(M) 0.03 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR TODAY TIMES DAILY(M) 0.02 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR INFO INDIA DAILY(M) 0.01 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR SANMARG DAILY(M) 0.02 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ARYAN AGE DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR BANGLA MORCHA DAILY(M) 0.01 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR Total 0.11 ANDHRA PRADESH DECCAN CHRONICLE DAILY(M) 0.01 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA BHOOMI DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA JYOTHI DAILY(M) 0.01 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRABHA DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA PRADESH ASHRAYA DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA PRADESH RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA PRADESH SAKSHI DAILY(M) 0.02 ANDHRA PRADESH TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA PRADESH CITY TIMES DAILY(M) 0.00 ANDHRA -

India Media Outlets

India Media Directory India Newswire 1st Headlines A India News Aaj Tak Aajkaal Aajkal Adinor Sombad Adyar Times Afternoon Despatch and Courier Afternoon Voice Agra News Agri Watch Ahmedabad Mirror Ajir Asom Ajir Dainik Batori Ajit Akila Al Hindelyom All India News Amar Ujala Amar Ujala Ananda Bazar Patrika Ananda Vikatan Anandabazar Patrika Andaman Chronicle Andhra Bhoomi Andhra Jyothi Andhra News Andolana Anna Nagar Times Anweshanam Apna Samachar Arunachal Times Asia Times Asian Age Asomiya Pratidin Assam Live Assam Tribune Assamiya Khabor Aurangabad Times BTV IN Bangalore Mirror Bartaman Patrika Bengal Net Bharat Observer Big News Network Bihar Times Bombay News Bombay Samachar Business Line Business Standard Business Today Business World Business and Economy CNBC TV18 CNN IBN Cashmere News Central Chronicle Charhdikala Charhdikala Chennai Online Chennai Vision Chitralekha Chitralekha Chitralekha Citizen Matters Corporate India DD News DLA AM DNA Daily Aftab Daily Desher Katha Daily Thanthi Dainik Agradoot Dainik Aikya Dainik Bhaskar Dainik Bhaskar Dainik Ekmat Dainik Jagran Dainik Jagran Dainik Navajyoti Dainik Sandhya Prakash Dainik Statesman Dainik Suprovat Dalal Street Darjeeling Times Day After Deccan Chronicle Deccan Chronicle Deccan Herald Deepika Dehradun Classified Desh Videsh Times Deshabhimani Deshbandhu Deshonnati Dharitri Dinakaran Dinakaran Dinalipi Dinamalar Dinamani Dinathanthi Dinathanthi Divya Bhaskar Divya Bhaskar E Ahmadnagar E Pao Eastern Mirror Economic Times Economic Times Economic Times Economic and Political