Partnership Working in Small Rural Primary Schools: the Best of Both Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board Meeting Minutes and Report Extracts

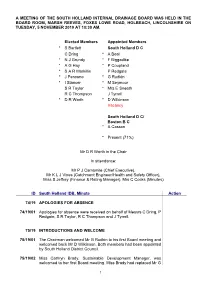

A MEETING OF THE SOUTH HOLLAND INTERNAL DRAINAGE BOARD WAS HELD IN THE BOARD ROOM, MARSH REEVES, FOXES LOWE ROAD, HOLBEACH, LINCOLNSHIRE ON TUESDAY, 5 NOVEMBER 2019 AT 10:30 AM. Elected Members Appointed Members * S Bartlett South Holland D C C Dring * A Beal * N J Grundy * F Biggadike * A G Hay * P Coupland * S A R Markillie P Redgate * J Perowne * G Rudkin * I Stancer * M Seymour S R Taylor * Mrs E Sneath R C Thompson J Tyrrell * D R Worth * D Wilkinson Vacancy South Holland D C/ Boston B C * A Casson * Present (71%) Mr D R Worth in the Chair In attendance: Mr P J Camamile (Chief Executive), Mr K L J Vines (Catchment Engineer/Health and Safety Officer), Miss S Jeffrey (Finance & Rating Manager), Mrs C Cocks (Minutes) ID South Holland IDB, Minute Action 74/19 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 74/19/01 Apologies for absence were received on behalf of Messrs C Dring, P Redgate, S R Taylor, R C Thompson and J Tyrrell. 75/19 INTRODUCTIONS AND WELCOME 75/19/01 The Chairman welcomed Mr G Rudkin to his first Board meeting and welcomed back Mr D Wilkinson. Both members had been appointed by South Holland District Council. 75/19/02 Miss Cathryn Brady, Sustainable Development Manager, was welcomed to her first Board meeting. Miss Brady had replaced Mr G 1 ID South Holland IDB, Minute Action Brown, Flood and Water Manager who had recently left the WMA Group and was now working for the National Trust. 76/19 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 76/19/01 Mr S A R Markillie declared an interest in agenda item 20 (2) of the Consortium Matters Schedule of Paid Accounts in respect of a payment made to his business with regard to his duties as WMA Chairman. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of a County Councillor

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED South Holland District Council Area of Lincolnshire County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for Crowland Electoral Division Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* FINISTER Elder Cottage, Liberal Ramkaran Hendy Robin Charles James Jekils Bank, Democrat Anne Elizabeth * King Jenny Edward Moulton Eaugate, Mayley Christine ** King Chris Spalding, Tippler Paula Maryan Alison PE12 0SY Rawden Richard Corrigan Emma Rawden Helen KIRK 9 Winthorpe Labour Party Mcfarlane Sean * Mason Phyllis E Darryl Baird Road, Lincoln, Kennerley David ** Horton June LN6 3PG Wilson Ruth E Robertson Wilson Michael J R Josephine A Sumner Brian Sancaster George L Clay Michael PEPPER 61A South Street, The Astill J * Ward N W Nigel Harry Crowland, Conservative Parnell John ** Atkinson T M PE6 0AH Party Candidate Boot R Quince G Clough P Elphee C Haselgrove P Slater N The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Wednesday 5 April 2017 Anna Graves Deputy Returning Officer Printed and published by the Deputy Returning Officer, Council Offices, Priory Road, Spalding, Lincolnshire, PE11 2XE STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED South Holland District Council Area of Lincolnshire County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County -

Community Events

COMMUNITY EVENTS Contact Us 01406 701006 or 01406 701013 www.transportedart.com transportedart @TransportedArt Transported is a strategic, community-focused programme which aims to get more people in Boston Borough and South Holland enjoying and participating in arts activities. It is supported through the Creative People and Places initiative What is Community Events? In 2014, the very successful Community Events strand worked with dozens of community organisers to bring arts activities to over twenty different local events, enabling thousands of people from all over Boston Borough and South Holland to experience quality, innovative and accessible art. In 2015, the Transported programme is focusing on developing long- term partnerships to promote sustainability. For this reason, this year, we are working with a smaller number of community event organisers from around Boston Borough and South Holland to collaboratively deliver a more streamlined programme of activity. Who is Zoomorphia? Zoomorphia provides participatory arts workshops run by artist Julie Willoughby. Julie specialises in family drop-in workshops at events and festivals. In 2015, Zoomorphia will be bringing a series of events with the theme “Paper Parade” to community events across Boston Borough and South Holland. Participants will learn simple techniques to turn colourful paper and card into large displays or individual souvenirs. Starting with templates, anybody can join in to engineer impressive 3D masterpieces! Who is Rhubarb Theatre? Rhubarb Theatre has been creating high quality indoor and outdoor theatre for over 15 years Contact Us and have performed at festivals all over the UK, 01406 701006 including Glastonbury. This year they will be or 01406 701013 bringing a cartload of wonder for all ages to Boston www.transportedart.com Borough and South Holland in their street theatre transportedart performance ‘Bookworms’. -

WITHERN, a Good Vi!Lage on the Louth Road, 5 Miles N

CALCEWORTH HUNDRED. 515 WILLOUGHBY PARISH. tBowker Thomas *Smith Thomas Marked * are at Sloothby ; t at Brooks William, tSmith Joseph Mawthorpe; tat Bonthorpe; and Hasthorpe Wright Riehard,. the rest at Willoughby, or where Coppin George Habertoft specified. tDales Thomas SHOEl\UKEBS. PosT OFFICE at Sloothby. Letters tDavisonEdward *Gooding Chu.. via Spilsby tDawson Wm. La wrenee J obn Andre'llf Wm. vict. Willoughby Arms Eyre Thomas Stockdale John Dupre Rev Thomas, M.A., Rectory Hurdman Joseph SHOPKEEPERS. *Fairnell Thomas, beerhouse Emperingham Banks John Freshney Charles, wheelwright Hurdman Wm., *Sharp John Lenton George, miller and baker Manor House *Sylvester Henry *Parkinson Wm. vict. Wheat Sheaf *Lenton Eardley V essey Geo. Wm. Robin son John, beerhouse *LillJohn TAILORS. Somerville George, station mas~er Lusby Gresswell, *Blackburn Wm. Taylor J ames, vict. Railway Tav. Hasthorpe Evison Wm. Whaley Robert, schoolmaster *Sanderson Thos. RAILWAY White Charles, blacksmith Sargisson Joseph Trains three times. BUTCHERS. I FARMERS. Shelton Rd. Mar- a day :Banks John Bassitt John ton, Hogsbeck Vessey George I •Bemrose Lucas WITHERN, a good vi!lage on the Louth road, 5 miles N. by W ~ of Alford, has in its parish 503 inhabitants and 2669 acres of land, including 253 acres in the hamlet of Stain or Stane, which is 3! miles N.E. of Withern, and pays tithes to Mablethorpe St. Mary,. and had anciently a church, which was a rectory, valued in K.B. at .£5. 6s. ld., but has now only a few cottages. Withern was formerly a seat of the Fitzwilliams, who had another mansion at Mablethorpe,. as noticed at page 505. -

South Holland District Council 5-Year Housing Land Supply Assessment

South Holland District Council 5-year Housing Land Supply Assessment (as at 31st March 2019) Published May 2019 Contents 1.0 Background ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 South Holland District’s 5-year housing requirement ................................................. 1 3.0 What is South Holland District’s deliverable housing supply? .................................... 2 Approach to Windfalls ...................................................................................................... 3 Overall Supply .................................................................................................................. 3 4.0 5-Year Land Supply Position for 1st April 2019 – 31st March 2024 ........................... 4 5.0 Recent trends ............................................................................................................. 5 6.0 Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 6 Appendix A: Large Sites ...................................................................................................... 7 Appendix B: Small Sites ..................................................................................................... 14 Appendix C: Allocations without Planning Permission (Local Plan Appendix 4) ................ 26 1.0 Background 1.1 Paragraph 73 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) requires Councils to “identify and update annually -

LINCOLNSHIRE. HAB 621 Swift Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY .J LINCOLNSHIRE. HAB 621 Swift Mrs. Caroline, Mort<ln Bourn Ward George, Keal Coates, Spilsby Wilson Robert, Bas!lingham, Newark tSwift W. E.Lumley rd.SkegnessR.S.O Ward John, Anderby, Alford Wilson William, 142 Freeman street, Taft David, Helpringham, Sleaford tWard Thomas, 47 Market pl. Boston Great Grimsby Talbot Mrs. Elizh. Ba':!singham, Newark Ward Wm. jun. Great Hale, Sleaford Winn Misses Selina Mary & Margaret Tate Henry, SouthKillingholme, Ulceby Ward Wm.Ailen,Hillingboro',Falkinghm Ellen, Fulletby, Horncastle TateJobn H.86 Freeman st.Gt.Grimsby Wardale Matt. 145 Newark rd. Lincoln Withers John Thomas, I03 'Pasture Tayles Thomas, 55 East st. Horncastle tWarren Edward, Little London, Long itreet, Weelsby, Great Grimsby TaylorMrs.AnnM.2 Lime st.Gt.Grimsby Sutton, Wisbech Withers J. 26 Pasture st. Great Grimsby TaylorGeo. Wm. Dowsby, Falkingham WarsopM.North st.Crowland,Peterboro' Withers Sl. 66 Holles st. Great Grimsby Taylor Henry, 6o East street, Stamford WassJ.T.Newportst.Barton-on-Hurnber Wood & Horton, 195 Victor street, New Taylor Henry, Martin, Lincoln Watchorn E. Colsterworth, Grantham Clee, Great Grimsby Taylor Henry, Trusthorpe, Alford Watchorn Mrs. J. Gt. Ponton,Grantham Wood Miss E. 29 Wide Bargate, Boston Taylor John T. Burringham, Doncaster Waterhouse Alex.I Spital ter.Gainsboro' Wood E. 29 Sandsfield la. Gainsborough Taylor Mrs. Mary, North Searle,Newark Waterman John, Belchford, Horncastle ·wood Hy. Burgh-on-the-Marsh R.S.O Taylor Mrs. M.3o St.Andrew st. Lincoln Watkin&Forman,54Shakespear st.Lncln Wood John, Metheringham, Lincoln Taylor Waiter Ernest,I6 High st. Boston WatkinJas.44 & 46 Trinity st.Gainsboro' Woodcock Geo. 70 Newark rd. -

1872 Moulton and Other Parts of Holland

• llolbeach Trades Diredory. J arvis Edward, Back lane Proctor Abraha.m, Pennyhill hous& VETERINARY SURGEONS. Leak John, High street Williams John, Victori~ street Dohson Robert W. Albert street Lewin John, Church street Maddock William, St. John's SADDLERS .AND HARNESS Kirkby George, Ba.rringtonga.te Nicholls Robert, Pennyhill MAKERS. WATCHMAKERS AND Presgrave John, Chapel street Coupland Eno, Market plaM Stephenson Robert, Hurn Simpson Thomas, High street JEWELLERS. Stevenson John, Fen Triffit Joseph, High street Barnes Thomas T. High street Taylor Georga, St. :Mark's SHOPKEEPERS. Bradley Mark, West end W estmoreland George, High street Lemon F. G. High st; & Baines Henry, Church street Sutton brdg IRONMONGERS. Clark Thomas, Drove Rippin Mrs Ann, Church street Guy Thoma~ (and gas:fitter), High st Coulson Thomas, St. John's WHEELWRIGHTS, Snarey William, West end Dollin William, Clough Elms Robert, Church street Bailey William, St. Matthew's W aite Charles, High street Castle William, Drove Moslin Jesse, High street Gregory Mrs Sarah, Albert street Hackney John, West end Kirton William, Littlebury street JOINERS AND BUILDERS. Helstrip Mrs Mary A. High street Mashford Charles, High street Chappell Joseph, (contractr) High st Matthews Michael, Bank Simpson Thomas W. Hurn Fawn James, Albert street May Thomas G. High street W almsley William, Fen Gilder Thomas, High street Ravell Mrs Sarah, West end Wicks Edward, St. Mark's Hardy Charles, St. John's street Savidge Joseph, Church street Wicks Francis, Hurn Haythorpe John & Zachariah, Bank Scott John Thomas, Bank Woods Ephraim, Washway Smith George H, Albert street West William F. Clough WINE &l SPIRIT MERCHTS~ Woolley John, Bank LAND SURVEYORS. -

Lincolnshire. Louth

DIRECI'ORY. J LINCOLNSHIRE. LOUTH. 323 Mary, Donington-upon-Bain, Elkington North, Elkington Clerk to the Commissioners of Louth Navigation, Porter South, Farforth with Maidenwell, Fotherby, Fulstow, Gay Wilson, Westgate ton-le-Marsh, Gayton-le-"\\'old, Grains by, Grainthorpe, Clerk to Commissioners of Taxes for the Division of Louth Grimblethorpe, Little Grimsby, Grimoldby, Hainton, Hal Eske & Loughborough, Richard Whitton, 4 Upgate lin,o1on, Hagnaby with Hannah, Haugh, Haugham, Holton Clerk to King Edward VI. 's Grammar School, to Louth le-Clay, Keddington, Kelstern, Lamcroft, Legbourne, Hospital Foundation & to Phillipson's & Aklam's Charities, Louth, Louth Park, Ludborough, Ludford Magna, Lud Henry Frederic Valentine Falkner, 34 Eastgate ford Parva, Mablethorpe St. Mary, Mablethorpe St. Collector of Poor Rates, Charles Wilson, 27 .Aswell street Peter, Maltby-le-Marsh, Manby, Marshchapel, Muckton, Collector of Tolls for Louth Navigation, Henry Smith, Ormsby North, Oxcombe, Raithby-cum-:.Vlaltby, Reston Riverhead North, Reston South, Ruckland, Saleby with 'fhores Coroner for Louth District, Frederick Sharpley, Cannon thorpe, Saltfleetby all Saints, Saltfleetby St. Clement, street; deputy, Herbert Sharpley, I Cannon street Salttleetby St. Peter, Skidbrook & Saltfleet, Somercotes County Treasurer to Lindsey District, Wm.Garfit,Mercer row North, Somercotes South, Stenigot, Stewton, Strubby Examiner of Weights & Measures for Louth district of with Woodthorpe, Swaby, 'fathwell, 'fetney, 'fheddle County, .Alfred Rippin, Eastgate thorpe All Saints, Theddlethorpe St. Helen, Thoresby H. M. Inspector of Schools, J oseph Wilson, 59 Westgate ; North, Thoresby South, Tothill, Trusthorpe, Utterby assistant, Benjamin Johnson, Sydenham ter. Newmarket Waith, Walmsgate, Welton-le-Wold, Willingham South, Inland Revenue Officers, William John Gamble & Warwick Withcall, Withern, Worlaby, Wyham with Cadeby, Wyke James Rundle, 5 New street ham East & Yarborough. -

Polling District and Polling Places Review 2019

Parliamentary Current Proposed Polling Places Feedback on polling stations during Acting Returning Elector Parish Ward Parish District Ward County Constituency Polling Polling used at the May 2019 elections Officer's comments/ Division District District May 2019 proposal Elections South Holland & SAD1 - CRD1 2,054 East Crowland Crowland and Crowland Crowland The Deepings Crowland East No polling station issues reported by Deeping St Parish Rooms, Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Nicholas Hall Street, Officer change Crowland South Holland & SAE - CRD2 Royal British 1,470 West Crowland Crowland and Crowland No polling station issues reported by The Deepings Crowland West Legion Hall, 65 Deeping St Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Broadway, Nicholas Officer change Crowland South Holland & SAF1 - CRD3 1,116 Deeping St Deeping St Crowland and Crowland Deeping St The Deepings Deeping St Nicholas Nicholas Deeping St Nicholas Nicholas No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Parish Church, Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Recommend: no Main Road, Officer change Deeping St Nicholas South Holland & SAF2- Deeping CRD4 Deeping St 222 Deeping St Deeping St Crowland and Crowland The Deepings St Nicholas Nicholas New polling station in 2019 Nicholas Nicholas Deeping St Primary No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Recommend: no School, Main Polling Station Inspector or Presiding change Road, Hop Officer Hole South Holland & SAF3 - Tongue CRD5 177 Tongue End Deeping St Crowland and Spalding Comments taken on The Deepings End Nicholas Deeping St Elloe Deeping St board - situated No polling station issues reported by Nicholas Nicholas outside the parish ward Polling Station Inspector or Presiding Primary due to lack of available Officer - concern raised by local School, Main premises, however, the councillor with regard to lack of polling Road, Hop current situation works station within the parish ward. -

A New Beginning for Swineshead St Mary's Primary School

www.emmausfederation.co.uk Admission arrangements for Community and Voluntary Controlled Primary Schools for 2018 intake The County Council has delegated to the governing bodies of individual community and controlled schools the decisions about which children to admit. Every community and controlled school must apply the County Council’s oversubscription criteria shown below if they receive more applications than available places. Arrangements for applications for places in the normal year of intake (Reception in Primary and Infant schools and year 3 in Junior schools) will be made in accordance with Lincolnshire County Council's co‐ordinated admission arrangements. Lincolnshire residents can apply online www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions, by telephone or by requesting a paper application. Residents in other areas must apply through their home local authority. Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools will use the Lincolnshire County Council's timetable published online for these applications and the relevant Local Authority will make the offers of places on their behalf as required by the School Admissions Code. In accordance with legislation the allocation of places for children with the following will take place first; Statement of Special Educational Needs (Education Act 1996) or Education, Health and Care Plan (Children and Families Act 2014) where the school is named. We will then allocate remaining places in accordance with this policy. For entry into reception and year 3 in September we will allocate places to parents who make an application before we consider any parent who has not made one. Attending a nursery or a pre-school does not give any priority within the oversubscription criteria for a place in a school. -

East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN ALTERATION 1999 The Local Plan has the following main aims:- x to translate the broad policies of the Structure Plan into specific planning policies and proposals relevant to the East Lindsey District. It will show these on a Proposals Map with inset maps as necessary x to make policies against which all planning applications will be judged; x to direct and control the development and use of land; (to control development so that it is in the best interests of the public and the environment and also to highlight and promote the type of development which would benefit the District from a social, economic or environmental point of view. In particular, the Plan aims to emphasise the economic growth potential of the District); and x to bring local planning issues to the public's attention. East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Page The Aims of the Plan 3 How The Policies Have Been Formed 4 The Format of the Plan 5 The Monitoring, Review and Implementation of the Plan 5 East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 2 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN 1.1. The East Lindsey Local Plan is the first statutory Local Plan to cover the whole of the District. It has updated, and takes over from all previous formal and informal Local Plans, Village Plans and Village Development Guidelines. It complements the Lincolnshire County Structure Plan but differs from it in quite a significant way. The Structure Plan deals with broad strategic issues and its generally-worded policies do not relate to particular sites. -

Lincolnshire. Holland Fen

DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE. HOLLAND FEN. 241 Moyses Ehzabeth (Mrs.), Rose & Crown Sissons Mark, beer retailer, Back lane Tinsley Joseph, farmer, Penny hill P.H. Holbeach burn Sketcher David, shopkeeper, Church st Tinsley William (trustees of), farmers, Musk Hy. farmer, Hurdle Tree bank Sketcher George, beer retailer, High st Holbeach drove Neale Rd. gasfitter & beer ret. High st Slator Abraham, blacksmith, Chapel st TinsleyWm.Hy.farmer,Holbeachmarsh Oldershaw Rd. Wm. frmr. Holbeach Fen Smith Amelia (Mrs.), baker, West end Townsend Jas. photog-rapher, High st Parsons Joseph Walker, farmer Smith George, threshing machine Triffitt Josiah, saddler, harness & horse Patehett John Sharp, farmer & potato owner, Holbeach St. Matthew's collar maker, lamp, brush & general merchant, Lewins lane Smith George Hill, carpenter & builder, warehouse & vendor of patent medi Paterson William, painter, ·west end Albert street cines, High street PearS(m Chas. fanner, Holbeach bank Smith Henry, bricklayer, Stukeley rd V ere George, hair dresser, High street Pearson Mary (Miss), milliner, High st Smith Joseph, boot maker, High street Vincent John, farmer, Boston road Penney Henry, higgler, Stukeley road SmithThos. (Mrs.), farmer, Welbourne la Vise A.mbrose Blithe, surgeon &medical Pennington George Caudwell, farmer, Smith Wm. Ram inn, Holbeach drove officer & public vaccinator, Holbeach Barringtonga to Snarey \\'illiam, ironmonger, West end South district & admiralty surgeon Peteh Alfred, fish curer, Church street Smart Wm. Jibb, shopkeeper, High st & agent, Abbotts Manor house Phenix Marshall,farmer,Holbeach drive Sprotberry John, boot maker, High st Waite David Parrinder, farmer, Green- Phillimore John, String of Horses P.H. Stableforth William Bennett, solicitor & field house Boston road commissioner to administer oaths, Walker Chas.