Narrative Strategies in the Marble Faun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorne's Concept of the Creative Process Thesis

48 BSI 78 HAWTHORNE'S CONCEPT OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Retta F. Holland, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HAWTHORNEIS DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER 1 II. PREPARATION FOR CREATIVITY: PRELIMINARY STEPS AND EXTRINSIC CONDITIONS 21 III. CREATIVITY: CONDITIONS OF THE MIND 40 IV. HAWTHORNE ON THE NATURE OF ART AND ARTISTS 67 V. CONCLUSION 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii CHAPTER I HAWTHORNE'S DEVELOPMENT AS A WRITER Early in his life Nathaniel Hawthorne decided that he would become a writer. In a letter to his mother when he was seventeen years old, he weighed the possibilities of entering other professions against his inclinations and concluded by asking her what she thought of his becoming a writer. He demonstrated an awareness of some of the disappointments a writer must face by stating that authors are always "poor devils." This realistic attitude was to help him endure the obscurity and lack of reward during the early years of his career. As in many of his letters, he concluded this letter to his mother with a literary reference to describe how he felt about making a decision that would determine how he was to spend his life.1 It was an important decision for him to make, but consciously or unintentionally, he had been pre- paring for such a decision for several years. The build-up to his writing was reading. Although there were no writers on either side of Hawthorne's family, there was a strong appreciation for literature. -

Hawthorne's Use of Mirror Symbolism in His Writings

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY CQ COLLEGE COLLECTION Gift of Jane './nicker lie lie tt KSLLSTT, JANS WHICKER. Hawthorne's Use of Mirror Symbolism in His Writings. (1968) Directed by Dr. Robert 0. Steohens. pp. 60 Ihroughout the course of Nathaniel Hawthorne's writin* one notes an extensive use of mirrors and other reflecting objects—brooks, lakes, fountains, pools, suits of armor, soao bubbles, the Duoils of oeople's eyes, and others. Surprisingly enough, few scholars and critics have had much to say about this slgnigiCRnt mirror symbolism; perhaps Hawthorne succeeded so well In concealing; these images that they exoress meaning without directing attention to their Dresence. Nevertheless, they are very much in evidence and for a very definite purpose. Hawthorne, whose works cover the problem of moral growth in man, was attempting to show mankind that only through an intense self-lntrosoectlon and self-examination of the interior of his Innermost bein°:—his heart—would he be able to live in an external world which often apoeared unintelligible to him; and through the utiliza- tion of mirror images., Hawthorne could often reveal truths hidden from the outer eyes of man. Hawthorne's Interest in mirrors is manifest from his earliest attempts in writing; indeed, he spoke of his imaerination as a mirror—it could reflect the fantasies from his haunted mind or the creations from his own heart. More Importantly, the mirror came to be for Hawthorne a kind of "magic" looking glass in which he could deoict settings, portray character, emphasize iraoortant moments, lend an air of the mysterious and the suoernatural, and disclose the meaning beneath the surface. -

'Troubled Joy' : the Paradox of the Female Figure in Nathaniel Hawthorne's Fiction

'TROUBLED JOY' : THE PARADOX OF THE FEMALE FIGURE IN NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE'S FICTION by Sciretk ROSEMARY GABY B.A. Hons. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA NOVEMBER 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Prefatory Note i Abstract .. ii Introduction .. 1 Background: The Figure of Woman in Nineteenth Century America 5 II Woman's Fatal Flaw: The Tales 25 III Hester Prynne 57 IV Zenobia and Priscilla 77 V Miriam and Hilda .. 96 Conclusion • • 115 Bibliography . 121 PREFATORY NOTE This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. (k9)9Acs-\ The style of presentation is primarily in accordance with the MLA Handbook (New York: Modern Language Association, 1977), but some features of style, notably the use of single quotation marks for quotations of words, phrases or short prose passages, have been determined by the Style Sheet of the Depart- ment of English, University of Tasmania. ABSTRACT The figure of woman is of central importance to the whole pre- sentation of meaning in Nathaniel Hawthorne's fiction. In comparison to other writers of the nineteenth century, and especially his male compatriots, Hawthorne grants the female figure a remarkable degree of prominence and significance in his works. His presentation of woman is noteworthy not only for the depth and subtlety with which his female characters are portrayed but also for the unique way in which he mani- pulates the standard female stereotypes to explore through symbolic suggestion the whole purpose of woman's existence and the foundations of her relations with man. -

The Destruction of Model and the Lost Story in the Marble Faun

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository The Destruction of Model and the Lost Story in The Marble Faun Yamaguchi, Shimpei 九州大学大学院 : 修士課程 https://doi.org/10.15017/4377721 出版情報:九大英文学. 60, pp.71-79, 2018-03-31. The Society of English Literature and Linguistics, Kyushu University バージョン: 権利関係: The Destruction of Model and the Lost Story in The Marble Faun Shimpei Yamaguchi The Marble Faun was published by Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1860. It is his last major work. He attempted some works after The Marble Faun, but he could not complete them in his life. His other three major works, The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851 ), The Blithedale Romance (1852), were successively published, while it took seven years for him to write The Marble Faun. Hawthorne was appointed as an American consul in Liverpool in 1853 and spent his life in Europe studying art until The Marble Faun was published, so that this work is different from the other three. It is more novelistic and mysterious. The Marble Faun has been accepted by many readers and criticized by many critics at the same time. Takaaki Niwa says in his book, The Dread Self-Portrait: Hawthorne and 'the Unpardonable Sin,' that the plot of The Marble Faun is inconsistent, and that it does not reveal enough mysteries. According to Randall Stewart; There had been, however, one persistent objection in the critical reception of the book- namely, that the author had not told with sufficient explicitness what actually happened in the story- and this objection Hawthorne good-naturedly took cognizance of in a short epilogue written in March and appended the second edition. -

Of Nathaniel Hawthorne

N9 se, ?69 THE FUNCTION OF THE PIVOT IN THE FICTION OF NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Paula Traynham Ricco, B. A. Denton, Texas May, 1980 Ricco, Paula Traynham, The Function of the Pivot in the Fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Master of Arts (Eng- lish), May, 1980, 144 pp., bibliography, 66 titles. In traditional romance, the hero takes a mythical journey into the underworLd where he meets and overcomes evil antagonists. Hawthorne has transferred much of that hero's role to a pivotal character whose paradoxical func- tion is to cause the central conflict in the tale or novel while remaining almost entirely passive himself. The movement of the tale or novel depends on the pivot's humanization, that is, his return to and integration within society. Works treated are "Alice Doane's Appeal," "Peter Goldthwaite's Treasure," "Roger Malvin's Burial," "Rap- paccini' s Daughter," "Lady Eleanore's Mantle," "The Minister's Black Veil," "The Antique Ring," "The Gentle Boy," Fanshawe, The Scarlet Letter, The House of the Seven Gables, The Blithedale Romance, and The Marble Faun. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ... ...... ...... 1 II. THE SHORTER WORKS.. ...... ... 11 III. FANSHAWE... ........ ......... 36 IV. THE SCARLET LETTER ..... ......... 48 V. THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES. ...... 65 VI. THE BLITHEDALE ROMANCE. ..... ..... 85 VII. THE MARBLE FAUN: OR, THE ROMANCE OF MONTE BENI ............... ....... 105 VIII. CONCLUSION.... ... ........ 127 BIBLIOGRAPHY . .......... ......... 139 Some of these mountains, that looked at no such mighty distance, were at least forty or fifty miles off, and appeared as if they were near neighbors and friends of other mountains, from which they were still farther removed. -

The Marble Faun: a Case Study of the Extra-Illustrated Volumes of the Marble Faun Published by Tauchnitz

The Transformation of The Marble Faun: A case study of the extra-illustrated volumes of The Marble Faun published by Tauchnitz by Andreane Balconi A thesis presented to Ryerson University and George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2011 ©Andreane Balconi Declarations I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis or dissertation. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis or dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. iii t·· .- I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis or dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I 11 Abstract This thesis explores the use and development of the photographically illustrated novel from a souvenir to a mass-market publication. An examination of three volumes of the Tauchnitz printing of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Marble Faun details how tourists and booksellers adapted the novel through the addition of albumen prints to create a unique souvenir. By 1889, the technological advances in the printing process, the demands of tourism and the photographic selections from the Tauchnitz volumes made it possible for Houghton, Mifflin and Company to publish an illustrated copy of The Marble Faun containing photogravure prints. Like the European title of the book - Transformation or , the Romance ofMonte Beni - this paper demonstrates how the Tauchnitz tourist produced souvenir copies of the novel evolved into a mass-market product. -

The Digital Faun

Abstract: This application proposes the creation of a digital, interactive, online critical edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun simulating nineteenth-century readers’ experience of the novel. Students and teachers could use this resource as an historical and intellectual guide to Rome—the setting of the novel—supplemented by annotations, chronologies and contextual notes, and mapping software to bring this classic of the American Renaissance to twenty-first century readers. The Digital Faun “The life of the flitting moment, existing in the antique shell of an age gone by, has a fascination which we do not find in either the past or present, taken by themselves.” —Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, Chapter 34 It has been years since readers have had access to an updated, annotated scholarly edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun, or The Romance of Monte Beni (1860), an oft-overlooked masterpiece the American Renaissance. Andrew Delbanco’s 2012 volume, for example, includes no footnotes,1 and the Norton Critical series has yet to produce an edition. The most recent, fully annotated version published as part of the Oxford World Classics is nearly a decade old.2 Although Hawthorne is better known to readers today for his short stories and novels—particularly Twice-Told Tales (1837), The Scarlet Letter (1850), and The House of the Seven Gables (1851)—The Marble Faun represents his late style, completed just four years before his death. Hawthorne himself considered it his best work, going so far as to claim, “If I have written anything well, it should be this romance; for I have never thought or felt more deeply, or taken more pains.”3 The Digital Faun, an online, hypertext edition of The Marble Faun for the twentieth-first century, would be worthy of Hawthorne’s own assessment of his most popular novel. -

Hawthorne Family Papers, [Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf358002w4 No online items Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Processed by The Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1996 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Literature --American Literature Guide to the Hawthorne Family BANC MSS 72/236 z 1 Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Guide to the Hawthorne Family Papers, [ca. 1834-1932] Collection number: BANC MSS 72/236 z The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: The Bancroft Library staff Date Completed: ca. 1972 Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1996 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Hawthorne Family Papers, Date (inclusive): [ca. 1834-1932] Collection Number: BANC MSS 72/236 z Creator: Hawthorne family Extent: Number of containers: 2 cartons, 6 boxes, 4 volumes and 1 oversize folder. Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Abstract: Primarily papers of Julian Hawthorne (correspondence, MSS of his writings and his poetry, journals and notebooks, scrapbooks, clippings, etc.), with a few papers also of his first wife, Minnie (Amelung) Hawthorne, and his second, Edith (Garrigues) Hawthorne. -

"The Marble Faun". Pp.79-83

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1992 Community Versus the Imperial Mind: Images of Civil Strife in Hawthorne's "The aM rble Faun". Henry Michael w Russell Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Russell, Henry Michael w, "Community Versus the Imperial Mind: Images of Civil Strife in Hawthorne's "The aM rble Faun"." (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5353. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5353 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Gothic Elements in Selected Fictional Works By

17c GOTHIC ELEMENTS IN SELECTED FICTIONAL WORKS BY NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Kurt T. Francis, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1985 Francis, Kurt T. Gothic Elements in Selected Fictional Works by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Master of Arts, December, 1985, 122 pp., bibliography, 44 titles. Gothicism is the primary feature of Nathaniel Hawthorne's fiction, and it is his skillin elevating Gothicism to the level of high art which makes him a great artist. Gothic elements are divided into six categories: Objects, Beings, Mental States, Practices and Actions, Architecture and Places, and Nature. Some devices from these six categories are documented in three of Hawthorne's stories ("Young Goodman Brown," "The Minister's Black Veil," and "Ethan Brown") and three of his romances (The Scarlet Letter, The House of the Seven Gables, and The Marble Faun). The identification of 142 instances of Hawthorne's use of Gothic elements in the above works demon- strates that Hawthorne is fundamentally a Gothic writer. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: OBJECTS AND BEINGS 16 CHAPTER II: MENTAL STATESAND PRACTICES AND ACTIONS 65 CHAPTER III: ARCHITECTURE AND PLACES, AND NATURE 89 CONCLUSION . ill BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 INTRODUCTION GOTHIC ELEMENTS IN SELECTED FICTIONAL WORKS BY NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE In the 121 years since the death of Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1864, a great amount of scholarly attention has been given to his many works of fiction. Writers and critics from Henry James on considered him to be a major force in mid-nineteenth-century Amer- ican fiction, a force rivalled only by Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville. -

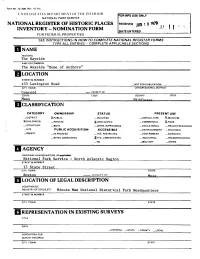

The Wayside ______AND/OR COMMON the Wayside "Home of Authors"______LOCATION

Form No 10-306 I Rev 10-74) UNITLDSTAThS DbPARTMbNT OHHMNItRlOR [FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED JUJJ 1 9 1979 INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS__________ | NAME HISTORIC The Wayside _____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON The Wayside "Home of Authors"______________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 455 Lexington Road _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Concord — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mass M-iH^looo-u- Q CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _OISTRICT XPUBLIC _ OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ?_MUSEUM X-BUILOING(S) _ PRIVATE XUNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .gYES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _!NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS National Park Service - North Atlantic Region STREET* NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE BOStOn ———— VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION Mace COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Minute Man National Historical Park Headquarters STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY TOWN i DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _ EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE .XGDOD RUINS JCALTERED _ FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Wayside, located on the north side of Route 2A, also known as "Battle Road," is part of Minute Man National Historical Park. The Wayside and its grounds extend just over four and a half acres and include the house, the barn, a well, a monument commemorating the centenary of Hawthorne's birth, and the remains of a slave's quarters. -

Counter-Monumentalism in the Search for American Identity In

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-30-2015 Counter-monumentalism in the Search for American Identity in Hawthorne's The cS arlet Letter & The aM rble Faun Carmen Mise Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC000114 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mise, Carmen, "Counter-monumentalism in the Search for American Identity in Hawthorne's The caS rlet Letter & The aM rble Faun" (2015). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2186. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2186 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida COUNTER-MONUMENTALISM IN THE SEARCH FOR AMERICAN IDENTITY IN HAWTHORNE’S THE SCARLET LETTER & THE MARBLE FAUN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Carmen Mise 2015 To: Dean Micheal R. Heithaus College of Arts of Sciences This thesis, written by Carmen Mise, and entitled, Counter-monumentalism in the Search for American Identity in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter & The Marble Faun, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________ Ana Luszczynska ______________________________ Nathaniel Cadle ______________________________ Bruce Harvey, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 30, 2015 The thesis of Carmen Mise is approved.