Lebanon's Green Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Loulwa Murtada

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Loulwa Murtada Recommended Citation Murtada, Loulwa, "Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1941. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1941 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Aversive Visions of Unanimity: Political Sectarianism in Lebanon Submitted to Professor Roderic Camp By Loulwa Murtada For Senior Thesis Fall 2017/ Spring 2018 23 April 2018 Abstract Sectarianism has shaped Lebanese culture since the establishment of the National Pact in 1943, and continues to be a pervasive roadblock to Lebanon’s path to development. This thesis explores the role of religion, politics, and Lebanon’s illegitimate government institutions in accentuating identity-based divisions, and fostering an environment for sectarianism to emerge. In order to do this, I begin by providing an analysis of Lebanon’s history and the rise and fall of major religious confessions as a means to explore the relationship between power-sharing arrangements and sectarianism, and to portray that sectarian identities are subject to change based on shifting power dynamics and political reforms. Next, I present different contexts in which sectarianism has amplified the country’s underdevelopment and fostered an environment for political instability, foreign and domestic intervention, lack of government accountability, and clientelism, among other factors, to occur. A case study into Iraq is then utilized to showcase the implications of implementing a Lebanese-style power-sharing arrangement elsewhere, and further evaluate its impact in constructing sectarian identities. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... -

Migration and Political Elite Formation: the Case of Lebanon

LEBANESE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY Migration and political elite formation: The case of Lebanon By Wahib Maalouf A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Migration Studies School of Arts and Sciences November 2018 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents and sister I am grateful for their endless love and support throughout my life v ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Paul Tabar, for giving me the opportunity to work on this interesting and challenging project. Dr. Tabar read several drafts and offered incisive comments that helped refine various sections of this thesis. I thank him for his generosity and for the numerous discussions that contributed to fostering my intellectual development throughout this journey. I also wish to extend my thanks to committee member Dr. Connie Christiansen, for her valuable remarks on parts of this thesis. My deep thanks also go to Sally Yousef for her assistance in transcribing most of the interviews conducted for this study, and to Wassim Abou Lteif and Makram Rabah, for facilitating the route to conducting some of the interviews used in this study. vi Migration and political elite formation: The case of Lebanon Wahib Maalouf ABSTRACT Migration has been impacting political elite formation in Lebanon since the 1930s, yet its role in that matter remained understudied. The main reason behind this is the relative prevalence in elite studies of “methodological nationalism”, which, in one of its variants, “confines the study of social processes to the political and geographic boundaries of a particular nation-state”. -

Political Attitudes Surrounding the Lebanese Presidency

Report Political Attitudes Surrounding the Lebanese Presidency Manuela Paraipan* 24 April 2014 Al Jazeera Center for Studies Tel: +974-44663454 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/ Lebanese members of parliament gather to elect the new president in downtown Beirut [AP Photo/Joseph Eid, Pool] This report is based on the results of a recent fact finding mission in Lebanon. The interlocutors we worked with included the heads of political parties, Members of Parliament, clergy, prominent figures from civil society and political parties and members of the security forces. The participants were open to dialog and constructive debate and added insight into current state of affairs in the country, post the formation of a government and prior to the election of a new president. The Lebanese Political Model and the Presidency In the quarter century since the signing of the 1989 Taef Agreement, which brought an end to the country's 15-year-long Civil War, the Lebanese political system has been subject to a long series of stresses and shocks. The stresses have included the continued actions of powerful confessional-based political-military organizations operating beyond the scope of state control, the presence large numbers of foreign troops (both Syrian and Israeli) operating on Lebanese soil, the continued growth of a large, politically unrepresented refugee population (with Syrian refugees now substantially outnumbering Palestinian ones and refugees currently making up perhaps a quarter of the country's total population) and the growing tensions between the country's Sunni and Shia communities. The shocks have included the 2005 assassination of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, the damaged caused by the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah War and the spill-over effects of the ongoing Syrian Civil War. -

Report on the 12Th EP-Lebanon IPM, 17-19 June

European Parliament 2014-2019 Delegation for relations with the Mashreq countries 30.6.2015 MISSION REPORT 12th Interparliamentary meeting European Parliament - Lebanese Chamber of Deputies Delegation for Relations with Mashrek countries: Members of the mission: Marisa Matias (GUE/NGL) (Mission Chair) Ramona Nicole Manescu (EPP) Andrea Cozzolino (S&D) Cristina Winberg (EFDD) CR\1069259EN.doc PE554.164v01-00 EN United in diversity EN Introduction The overall aims of the mission were: To meet Lebanese authorities and institutional partners, in primis the Lebanese Chamber of Representatives; To discuss with Lebanese stakeholders the cooperation between Lebanon and the European Union, notably in light of the current review of the European Neighbourhood Policy; To accomplish a fact-finding mission to the Bekaa Valley in order to visit an informal Syrian refugee camp and a school, attended by Lebanese and refugee children; To meet Lebanese and Syrian civil society and NGOs; To assess with international, Lebanese and Syrian interlocutors the situation in neighbouring Syria, also in view of a possible ad hoc mission to Damascus; The programme of the visit included high-level meetings with the Prime Minister and Speaker of Parliament, the Ministers for Foreign Affairs and Social Affairs, the heads of the main political parties1, members of the Foreign Affairs Committee and of the Lebanon-EU friendship group of the Lebanese Parliament, the Intelligence Director of the Lebanese Armed Forces. The Delegation also met with representatives of international organisations, notably the United Nations, and with NGOs working mainly on refugee issues. The Delegation visited Syrian refugees in the Bekaa Valley in order to assess the situation on the ground. -

The Political Economy of Contemporary Le!Banon: a Study of the Reconstruction

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CONTEMPORARY LE!BANON: A STUDY OF THE RECONSTRUCTION by: Tom Pierre Najem A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Middle East Politics The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Supervisor: Professor Tim Niblock PhD Thesis 1997 The Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies University of Durham Autumn 1997 0 23 JAN 1998 ii ABS TRACT The general purpose of this study is to look at the post- war economic reconstruction of Lebanon. More specifically, our primary aim is to examine, within the context of development theory, the institutional arrangement for implementing the various reconstruction programmes. In order to address these points, we will need to examine several important issues: How the economic leadership of post-war Lebanon has developed; what the institutions providing economic leadership have been; what plans have been developed for Lebanon's reconstruction; what groups have participated in the reconstruction; and what the principal obstacles to the economic reconstruction of the country have been. We will argue that the institutional arrangement is inappropriate for implementing the recovery programme. In part, because of the institutional arrangement, the recovery programme has suffered, and it is conceivable that the programme may fail to strengthen the Lebanese economy. The information collected for this study originated from three main sources including: material obtained from library research in the U.K.,; material collected in Lebanon from organisations, institutions, and individuals involved in the recovery programme; and material acquired from a series of unstructured interviews conducted in Lebanon in the winter of 1997 with individuals intimately associated with the reconstruction, prominent opponents of the system, and general observers of the Lebanese scene. -

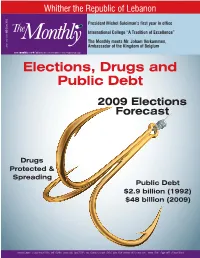

MONTHLY-E83-June09 Final.Indd

Whither the Republic of Lebanon President Michel Suleiman’s first year in office June 2009 | 83 International College “A Tradition of Excellence” The Monthly meets Mr. Joham Verkammen, Ambassador of the Kingdom of Belgium issue number www.iimonthly.com • Published by Information International sal Elections, Drugs and Public Debt 2009 Elections Forecast Drugs Protected & Spreading Public Debt $2.9 billion (1992) $48 billion (2009) Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros 2 iNDEX PAGE PAGE 4 Electoral law, results, blocs and elections forecast 35 Between Yesterday and Today LEADER 12 Drugs in Lebanon 36 Lebanon’s MPs Cultivation, traffickingand and Lebanese its spread among youth Parliamentary Elections 1960 - 2009 18 Public debt at USD 48 billion 37 From the series of 20 President Michel Suleiman’s first “Children Entertaining Stories”* year in office 38 Myth #24 21 Whither the Republic of Lebanon: Alexander, worshipper or fighter? Amnesty for drug crimes 39 Jumblatt and Syria 22 Violation of Civil Rights and Duties 40 Release of the four generals: 23 Salt Production End of one phase, beginning of another 24 Syndicate of Petroleum Companies Workers and 42 International Media Employees in Lebanon Iran’s ‘New Proposal’ & The USA 26 International College 44 Karm Al Muhr 28 Lebanese International University 45 Harb families 30 The Monthly meets Mr. 46 Education Enrollment in the Arab Joham Verkammen, World Ambassador of the Kingdom of Belgium 47 Real Estate Index: April 2009 32 High Blood Pressure by Dr. -

Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon

Social Classes This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon Fawwaz Traboulsi This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Middle East Office. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the opinion of the Foundation. Content 1- Methodology ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2- From Liberalism to Neoliberalism .................................................................................................................................... 23 3- The Oligarchy ................................................................................................................................................................................. 30 4- The Middle Classes............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 44 5- The Working Classes ................................................................................................................................................................. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Political economy of contemporary Lebanon : a study of the reconstruction. Najem, Tom Pierre How to cite: Najem, Tom Pierre (1997) Political economy of contemporary Lebanon : a study of the reconstruction., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1638/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CONTEMPORARY LE!BANON: A STUDY OF THE RECONSTRUCTION by: Tom Pierre Najem A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Middle East Politics The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Supervisor: Professor Tim Niblock PhD Thesis 1997 The Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies University of Durham Autumn 1997 0 23 JAN 1998 ii ABS TRACT The general purpose of this study is to look at the post- war economic reconstruction of Lebanon. -

The Social Stability Context in the Nabatieh & Bint Jbeil Qazas

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. The Social Stability Context in the Nabatieh & Bint Jbeil Qazas Conflict Analysis Report - March 2016 Supported by: This report was written by Muzna Al-Masri, as part of a conflict analysis consultancy for UNDP Peacebuilding in Lebanon Project to inform and support UNDP programming, as well as interventions from other partners in the frame of the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP). This report is the first of a series of four successive reports, all targeting specific areas of Lebanon which have not been covered by previous similar research. Through these reports, UNDP is aiming at providing quality analysis to LCRP Partners on the evolution of local dynamics, highlighting how the local and structural issues have been impacted and interact with the consequences of the Syrian crisis in Lebanon. This report has been supported by DFID. For any further information please contact directly: Bastien Revel, UNDP Social Stability Sector Coordinator at [email protected] and Joanna Nassar, UNDP Peacebuilding in Lebanon Project Manager at [email protected] Report written by Muzna Al-Masri Research Assistance: Marianna Altabbaa The author wishes to thank all the interviewees, both Lebanese and Syrian, for their time and input. The author also wishes to thank Dr. Hassan Fakih of the Nabatieh Security cell, as well as members of commercial and civil society organizations who have helped in data collection. Special thanks to Ms. Layla Serhan and Mr. Dany Kalakech for their input and much appreciated logistical support during field work. The author and UNDP wish to thank members of the Social Stability and Livelihoods working group in the South, in addition to UNHCR for their input on earlier draft of this report. -

EU EOM Lebanon FR

EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS LEBANON 2005 FINAL REPORT EU Election Observation Mission to Lebanon 2005 - 2 - Final Report on the Parliamentary Elections Table of contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Executive Summary and Recommendations 6 3. Political and Statistical background 12 3.1. Data on electoral population and territory 12 3.2. Overview of Parliamentary election after the war 13 3.3. Common features of post-war elections 14 3.4. Overview of post-war results 18 4. Political landscape of the 2005 elections 20 4.1. Pre-election context and campaign 20 4.2. Main features of the campaign 24 4.3. Overview of 2005 results 25 5. Legal and Institutional framework 36 5.1. Legal framework and the electoral system 36 5.1.1. Suffrage rights 38 5.1.2. Campaign finance 39 5.1.3. Law on associations 40 5.1.4. Candidates and electoral tickets 41 5.2 Election Administration 42 5.2.1 The Ministry of Interior 43 5.2.2 Local election administration 43 5.2.3 Voting procedures 44 5.2.4 Civic and voter registration 45 5.2.5 Voter card system 47 5.2.6 Candidate registration 48 5.2.7 Candidate and non partisan observers 49 5.2.8 Election related complaints 50 5.3 Media framework 52 6. Observation of the 2005 elections 55 6.1. Media monitoring results 58 EU Election Observation Mission to Lebanon 2005 - 3 - Final Report on the Parliamentary Elections Annexes Composition of the new Parliament 61 Media monitoring results 66 This report was produced by the EU Election Observation Mission and presents the EU EOM’s findings on the Parliamentary elections in Lebanon.