The Future of Environmental History Needs and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree In

What’s the Difference Between the B.A. and B.S. Degree in ES? 8.1.20 If you’re thinking about pursuing Environmental Studies (ES) at UC Santa Barbara the first important decision you have to make is choosing which degree to pursue, the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Environmental Studies. While both majors are similar in design and stress the importance of understanding the complex interrelationships between the humanities, social sciences, and natural science disciplines, having two degree options allows students maximum flexibility to choose a major that best fits their environmental interests and goals. In this document we provide a detailed comparison of the academic requirements of the B.A. and B.S. major so one can understand the differences and can make an educated decision. Given your decision will also be based on what you want to do after graduation we thought it might be helpful to also highlight just a few example career paths each degree might lead to. Just remember, no matter which major you choose, your decision should be based on what you believe will ultimately make you happy. Simply put, the B.A. degree in ES is the more interdisciplinary major, requiring a swath of introductory courses in the humanities, social, physical, and natural sciences. It stresses the importance of comprehending basic social, cultural, and scientific theories and understanding how they interact with one another and play an important part of every environmental issue. While this degree will make one science literate, the degree offers maximum flexibility to select ES electives and outside concentration courses from just about every academic discipline at UCSB, including: arts, policy, culture, languages, humanities, and economics to name just a few. -

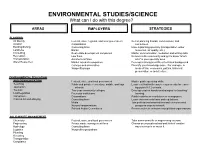

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What Can I Do with This Degree?

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES/SCIENCE What can I do with this degree? AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES PLANNING Air Quality Federal, state, regional, and local government Get on planning boards, commissions, and Aviation Corporations committees. Building/Zoning Consulting firms Have a planning specialty (transportation, water Land-Use Banks resources, air quality, etc.). Consulting Real estate development companies Master communication, mediation and writing skills. Recreation Law firms Network in the community and get to know "who's Transportation Architectural firms who" in your specialty area. Water Resources Market research companies Develop a strong scientific or technical background. Colleges and universities Diversify your knowledge base. For example, in Nonprofit groups areas of law, economics, politics, historical preservation, or architecture. ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION AND COMMUNICATION Federal, state, and local government Master public speaking skills. Teaching Public and private elementary, middle, and high Learn certification/licensure requirements for teach- Journalism schools ing public K-12 schools. Tourism Two-year community colleges Develop creative hands-on strategies for teaching/ Law Regulation Four-year institutions learning. Compliance Corporations Publish articles in newsletters or newspapers. Political Action/Lobbying Consulting firms Learn environmental laws and regulations. Media Join professional associations and environmental Nonprofit organizations groups as ways to network. Political Action Committees Become active in environmental -

Rcguha's Deep Ecology

R.C.Guha’s Deep Ecology The respected radical journalist Kirkpatrick sale recently celebrated “the passion of a new and growing movement that has become disenchanted with the environmental establishment. Decrying the narrowly economic goals of mainstream environmentalism, this new movement aims at nothing less than a philosophical and cultural revolution in human attitudes toward nature. Ramchandra Guha develop a critique of deep ecology from the perspective of a sympathetic outsider. Ramchandra Guha’s treatment of deep ecology is primarily historical and sociological, rather than philosophical, in nature. He makes two main arguments : first, that deep ecology is uniquely American. Second, that the social consequences of putting deep ecology into practice on a worldwide basis are very grave indeed. The defining characteristics of deep ecology are fourfold. First, deep ecology argues that the environmental movement must shift from an “anthropocentric” to a “bio-centric” perspective. The anthropocentric------ bio-centric distinction is accepted as axiomatic by deep ecologists, it structures their discourse, and much of the present discussions remains mired within it. The second characteristic of deep ecology is its focus on the preservation of unsploilt wilderness and the restoration of degraded areas to a more pristine condition – to the relative neglect of other issues on the environmental agenda. Historically, it represents a playing out of the preservationist and utilitarian dichotomy that has plagued American environmentalism since the turn of the century. Morally, it is an imperative that follows from the bio-centric perspective ; other species of plants and animals, and nature itself ,have an intrinsic right to exist. And finally, the preservation of wilderness also turns on a scientific argument – viz.; the value of biological diversity in stabilizing ecological regimes and in retaining a gene pool for future generations. -

Environmental Studies (CASNR) 1

Environmental Studies (CASNR) 1 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES College Requirements College Admission (CASNR) Requirements for admission into the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources (CASNR) are consistent with general University Description admission requirements (one unit equals one high school year): 4 units of English, 4 units of mathematics, 3 units of natural sciences, 3 units Website: esp.unl.edu (http://esp.unl.edu/) of social sciences, and 2 units of world language. Students must also The environmental studies major is designed for students who want to meet performance requirements: a 3.0 cumulative high school grade make a difference and contribute to solving environmental challenges point average OR an ACT composite of 20 or higher, writing portion not on a local to global scale. Solutions to challenges such as climate required OR a score of 1040 or higher on the SAT Critical Reading and change, pollution, and resource conservation require individuals who Math sections OR rank in the top one-half of graduating class; transfer have a broad-based knowledge in the natural and social sciences, as students must have a 2.0 (on a 4.0 scale) cumulative grade point average well as strength in a specific discipline. The environmental studies and 2.0 on the most recent term of attendance. For students entering major will provide the knowledge and skills needed for students to the PGA Golf Management degree program, a certified golf handicap work across disciplines and to be competitive in the job market. The of 12 or better (e.g., USGA handicap card) or written ability (MS Word environmental studies program uses a holistic approach and a framework file) equivalent to a 12 or better handicap by a PGA professional or high of sustainability. -

Environmental Studies

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES Richard Van Buskirk, Chair; Deke Gundersen The Environmental Studies Department (www.pacificu.edu/as/enviro/) in the College of Arts and Sciences provides students with an education that takes full advantage of Pacific University's liberal arts curriculum. In this program, students and faculty have opportunities to pursue interests that span a wide range of disciplines. In addition to the two full-time faculty members in the department, Environmental Studies offers the expertise of faculty affiliated with the program who are based in the disciplines of biology, chemistry, political science, economics, history, art, sociology, anthropology, philosophy and literature. This results in a wide range of opportunities to investigate environmental problems that cross traditional boundaries. Students in Environmental Studies can choose to apply their knowledge through research opportunities in unique nearby surroundings such as the coniferous forest of the John Blodgett Arboretum, the riparian corridors of the Gales Creek and Tualatin River watersheds, and the 750-acre Fernhill Wetlands. The B Street Permaculture Project (a 15-minute walk from campus) is a learning laboratory for sustainability that directly addresses the human component of environmental problem solving. Regionally, there are many exemplary resources available within a one- to two-hour drive of campus such as the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, Tillamook and Willapa Bays, and the forests of the Coast and Cascade Ranges. The proximity of Pacific University to study sites both wild and human-influenced is one of the main strengths of the Environmental Studies program. The Environmental Studies curriculum includes majors that lead to a Bachelor of Science (B.S.) or a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree. -

Useful Categories of Analysis in Environmental History

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 10-16-2014 Women and Gender: Useful Categories of Analysis in Environmental History Nancy Unger Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Social Justice Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Unger, N. (2014). Women and Gender: Useful Categories of Analysis in Environmental History. In A. Isenberg (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Environmental History. Oxford University Press, pp. 600-643. This material was originally published in Oxford Handbook of Environmental History edited by Andrew Isenberg, and has been reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. For permission to reuse this material, please visit http://www.oup.co.uk/academic/rights/permissions. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER 21 WOMEN AND GENDER Useful Categories of Analysis in Environmental History NANCY C. UNGER IN 1990, Carolyn Merchant proposed, in a roundtable discussion published in The Journal of American History, that gender perspective be added to the conceptual frameworks in environmental history. 1 Her proposal was expanded by Melissa Leach and Cathy Green in the British journal Environment and History in 1997. 2 The ongoing need for broader and more thoughtful and analytic investigations into the powerful relationship between gender and the environment throughout history was confirmed in 2001 by Richard White and Vera Norwood in "Environmental History, Retrospect and Prospect," a forum in the Pacific Historical Review. -

Teaching the Environmental Humanities International Perspectives and Practices

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ResearchSPace - Bath Spa University Teaching the Environmental Humanities International Perspectives and Practices EMILY O’ GORMAN Department of Geography and Planning, Macquarie University, Australia THOM VAN DOOREN Department of Gender and Cultural Studies, University of Sydney, Australia URSULA MÜNSTER Oslo School of Environmental Humanities, Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Olso, Norway JONI ADAMSON Department of English and Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University, USA CHRISTOF MAUCH Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, Germany SVERKER SÖRLIN, MARCO ARMIERO, KATI LINDSTRÖM Division of History of Science, Technology, and Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden DONNA HOUSTON Department of Geography and Planning, Macquarie University, Australia JOSÉ AUGUSTO PÁDUA Institute of History, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil KATE RIGBY Research Centre for Environmental Humanities, Bath Spa University, UK OWAIN JONES College of Liberal Arts, Bath Spa University, UK JUDY MOTION Environmental Humanities, University of New South Wales, Australia STEPHEN MUECKE School of Humanities, University of Adelaide, Australia Environmental Humanities 11:2 (November 2019) DOI 10.1215/22011919-7754545 © 2019 Each Author This is an open access article distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). 428 Environmental -

Environmental Studies Is Not for Turer, and Carol Goody As Our ES Our ES Students and Enhance the the Faint of Heart

Volume 1, Issue 1 Greetings from the Director 2007-2008 Being a faculty member or student Program Coordinator and Lec- valuable learning opportunities for in environmental studies is not for turer, and Carol Goody as our ES our ES students and enhance the the faint of heart. As a global Administrative Assistant. environmental understanding of all Skidmore students as they live and population, we face seemingly As was the case in 2002 when we learn on a more environmentally- insurmountable environmental first implemented the ES major, friendly campus. issues – climate change, water Skidmore students continue to be pollution, air pollution, loss of the driving force in ES. While we In addition to our strides on cam- biodiversity, compromised agricul- began the ES major with one pus, we have strengthened bridges tural productivity, and more. I’m graduate in 2002 (Jenna Ringel- with the surrounding community often asked how I remain positive heim, see page 2), our declared through the Water Resources Ini- while absorbed in such daunting majors and minors now number tiative (see insert) and our en- challenges on a day to day basis. It over sixty. Our ES students’ ac- hanced efforts on internship place- certainly helps that I have a stereo- complishments during their time at ments. Our community partners typical Midwestern disposition; I Skidmore (see page 3) and in their provide valuable learning opportu- fall firmly at the friendly end of post-Skidmore life (page 4) are nities for students and faculty alike the personality spectrum, I tend to nothing short of remarkable. Most and are just as much a part of our view the world through a rosy set rewarding for me, however, is the ES Program as our campus con- of lenses, and yes, I am a bit ob- willingness of our current students stituents. -

Environmental Worldviews, Ethics, and Sustainability 25

Environmental Worldviews, Ethics, and Sustainability 25 Biosphere 2—A Lesson in Humility C O R E C A S E S TUDY In 1991, eight scientists (four men and four women) were sealed sphere’s 25 small animal species went extinct. Before the 2-year inside Biosphere 2, a $200 million glass and steel enclosure period was up, all plant-pollinating insects went extinct, thereby designed to be a self-sustaining life-support system (Figure 25-1) dooming to extinction most of the plant species. that would add to our understanding of Biosphere 1: the earth’s Despite many problems, the facility’s waste and wastewater life-support system. were recycled. With much hard work, the Biospherians were A sealed system of interconnected domes was built in the also able to produce 80% of their food supply, despite rampant desert near Tucson, Arizona (USA). It contained artificial ecosys- weed growths, spurred by higher CO2 levels, that crowded out tems including a tropical rain forest, savanna, and desert, as well food crops. However, they suffered from persistent hunger and as lakes, streams, freshwater and saltwater wetlands, and a mini- weight loss. ocean with a coral reef. In the end, an expenditure of $200 million failed to maintain Biosphere 2 was designed to mimic the earth’s natural chemi- this life-support system for eight people for 2 years. Since 2007, cal recycling systems. Water evaporated from its ocean and other the University of Arizona has been leasing the Biosphere 2 facility aquatic systems and then condensed to provide rainfall over the for biological research and to provide environmental education tropical rain forest. -

Environmental-Studies.Pdf

Environmental Studies 1 Environmental Studies Directors of undergraduate studies: Michael Fotos ([email protected]) for B.A. students, Kealoha Freidenburg ([email protected]) for B.S. students; www.yale.edu/evst Environmental Studies offers the opportunity to examine human relations with their environments from diverse perspectives. The major encourages interdisciplinary study in (1) social sciences, including anthropology, political science, law, economics, and ethics; (2) humanities, to include history, literature, religion, and the arts; and (3) natural sciences, such as biology, ecology, human health, geology, and chemistry. Students work with faculty advisers and the director of undergraduate studies (DUS) to concentrate on some of the most pressing environmental and sustainability problems of our time: energy and climate change, food and agriculture, urbanism, biodiversity and conservation, human health, sustainable natural resource management, justice, markets, and governance. Students may pursue either a B.A. or a B.S. degree within Environmental Studies. The B.A. program is intended for students who wish to concentrate in the social sciences and humanities. The B.S. program encourages students to focus in the natural sciences, especially fields such as environmental health and medicine, ecology, and energy and climate change. Both degree programs culminate in a senior essay project that is commonly preceded by independent summer research. Prerequisites The B.A. degree program has no prerequisites. The B.S. degree program requires a natural science laboratory or field course focusing on research and analytic methods, and a term course in mathematics, physics, or statistics selected from MATH 112 or higher (excluding MATH 190), or PHYS 170 or higher, or S&DS 101 or higher; two-term lecture sequence in chemistry (or CHEM 170 or CHEM 167), and either the two-term biology introductory sequence BIOL 101, 102, 103 and 104, or EPS 125. -

Infosys Prize 2018

Infosys Science Foundation INFOSYS PRIZE 2018 LEPIDOPTERA – WINGS WITH SCALES Those brilliant pigments that create magical colors on the wings of a butterfly is chemistry in play. That the pattern and tint are governed by its genes is what we learn from the field of genetics. And how can we separate nanoscience from this mystical being? The ‘nano’ chitin or tiny scales on the wings reflect light to create a mosaic of iridescent hues. When you see blue, purple, or white on a butterfly, that’s a structural color, while orange, yellow, and black are pigments. How overwhelming is this complexity! And how mystical the butterfly looks as it soars into the sky, its tiny scales aiding the flow of air – a marvel of aerodynamics! We divide this universe into parts – physics, biology, geology, astronomy, psychology and so on, but nature does not categorize. And so every small and big discovery by scientists and researchers from diverse fields come together to create a deeper understanding of our vast and interconnected universe. Oh yes, the powder that brushes off on your fingers when you touch a butterfly’s wings are the tiny scales breaking off, and that ‘slipperiness’ helps the butterfly escape the trap. But that touch may perhaps sadly contribute towards its demise. A caution therefore that we must tread carefully lest we hurt our world, for when we disturb one part of the universe, we may unknowingly create a butterfly effect. ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE NAVAKANTA BHAT Professor, Indian Institute of Science, and Chairperson, Centre for Nano Science and Engineering, IISc, Bengaluru, India Navakanta Bhat is Professor of Electrical and Communications Engineering at Among his many awards are the Dr. -

HARRIET RITVO History Faculty E51-285 Massachusetts Institute Of

HARRIET RITVO History Faculty E51-285 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge MA 02139 617/253-6960 or 4965 (fax 253-9406) [email protected] Education Ph.D. Harvard University, 1975 Girton College, Cambridge University, 1968-69 A.B. Harvard University, magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 1968 Fellowships and Awards 2005- Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences 2002-3 Senior Fellowship, National Humanities Center 1999 Visiting Scholar, Humanities Research Institute, University of California at Irvine 1990 Whiting Writers' Award 1990 Guggenheim Fellowship 1990 Fellowship, National Humanities Center 1989 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship 1989 Visiting Fellowship, Clare Hall, Cambridge University 1985-86 Fellowship, Stanford Humanities Center 1984 Visiting Fellowship, Yale Center for British Art 1982 Old Dominion Fellowship (M.I.T.) 1969-74 Graduate Prize Fellowship (Ford Foundation) 1968-69 Isobel Briggs Traveling Fellowship Professional Experience Academic 1995- Arthur J. Conner Professor of History, MIT 1980-95 Assistant to Full Professor, MIT 1979-80 Lecturer, Humanities Department, MIT 1974-75 Lecturer in English, University of Massachusetts, Boston 1971-75 Teaching Fellow in History and Literature and in English, Harvard University Administrative 1999-2006 Head, History Faculty, MIT 1992-95 Associate Dean, School of Humanities and Social Science, MIT 1980-81 Assistant Director, Writing Program, MIT 1979-80 Assistant to the Dean, School of Humanities and Social Science, MIT 1977-79 Editor, Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1976-79 Staff Associate for Arts and Humanities, American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1975-76 Assistant Director, Office of Sponsored Research, Boston University Other 2006 Leader, Summer Seminar for Liberal Arts College Faculty ("Going Global: Environmental History and the Exchange of Animals, Plants, and Ideas"), National Humanities Center 2002-3 Marsh Book Prize Committee, American Society for Environmental History 2001- Editorial Board, Environmental History 1.