Download Necessary Forms and Templates for Any Specific Public Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thanh Hoa City Comprehensive Socioeconomic Development Project

Resettlement Plan Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Revised Project Number: 41013 March 2012 Viet Nam: Thanh Hoa City Comprehensive Socioeconomic Development Project Component 1: Urban Road Development and Component 4: Human Resource Development Prepared by Thanh Hoa Provincial People’s Committee The resettlement and ethnic minorities development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. THANH HOA PROVINCE PEOPLE’S COMMITEE PROVINCIAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT UNIT ------------------------------------ THANH HOA CITY COMPREHENSIVE SOCIOECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (No.2511 VIE - ADB LOAN) UPDATED RESETTLEMENT PLAN COMPONENTS 1 AND 4 Prepared by PROVINCIAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT UNIT February, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Annexes ................................................................................................................................................ 5 A. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 9 B. Project Description .................................................................................................................................... 13 Resettlement Plan - Component 1 and 4 1. Background ............................................................................................................................................ 13 2. Project’s Components ........................................................................................................................... -

Planned Relocationsinthe Mekong Delta: Asuccessful Model Forclimate

June 2015 PLANNED RELOCATIONS IN THE MEKONG DELTA: A SUCCESSFUL MODEL FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION, A CAUTIONARY TALE, OR BOTH? AUTHORED BY: Jane M. Chun Planned Relocations in the Mekong Delta Page ii The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings research are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication was generously provided by The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment. 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu © 2015 Brookings Institution Front Cover Photograph: A Vietnamese woman receiving fresh water after the floods in the Mekong Delta (EU/ECHO, March, 6, 2012). Planned Relocations in the Mekong Delta Page iii THE AUTHOR Jane M. Chun holds a PhD from the University of Oxford, where her research focused on the intersection of environmental change and stress, vulnerability, livelihoods and assets, and human mobility. She also holds an MA in international peace and conflict resolution from American University, and an MM and BA in classical music. Dr Chun has conducted research for a range of organizations on related topics, and has also worked as a humanitarian and development practitioner with agencies such as UNICEF, UNDP, and IOM. -

An Analysis of the Situation of Children and Women in Kon Tum Province

PEOPLE’S COMMITTEE OF KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN 1 AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AckNOWLEDGEMENTS This Situation Analysis was undertaken in 2013-2014 as part of the Social Policy and Governance Programme, under the framework of the Country Programme of Cooperation between the Government of Viet Nam and UNICEF in the period 2012-2016. This publication exemplifies the strong partnership between Kon Tum Province and UNICEF Viet Nam. The research was completed by a research team consisting of Edwin Shanks, Buon Krong Tuyet Nhung and Duong Quoc Hung with support from Vu Van Dam and Pham Ngoc Ha. Findings of the research were arrived at following intensive consultations with local stakeholders, during fieldwork in early 2013 and a consultation workshop in Kon Tum in July 2014. Inputs were received from experts from relevant provincial line departments, agencies and other organisations, including the People’s Council, the Provincial Communist Party, the Department of Planning and Investment, the Department of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs, the Department of Education, the Department of Health, the Provincial Statistics Office, the Department of Finance, the Social Protection Centre, the Women’s Union, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Provincial Centre for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation, the Committee for Ethnic Minorities, Department of Justice. Finalization and editing of the report was conducted by the UNICEF Viet Nam Country Office. -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING THE UNIVERSITY OF DA NANG ********************* Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT VIETNAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES DEVELOPMENT PROJECT – DA NANG UNIVERSITY SUBPROJECT (FUNDED BY WORLD BANK) Final Public Disclosure Authorized Project location: Hoa Quy ward, Ngu Hanh Son district, Da Nang city Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Da Nang – 2020 MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING THE UNIVERSITY OF DA NANG ********************* ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT VIETNAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITIES DEVELOPMENT PROJECT – DA NANG UNIVERSITY SUBPROJECT (FUNDED BY WORLD BANK) Final SUBPROJECT PROJECT OWNER: CONSULTING UNIT: THE UNIVERSITY OF DA NANG INTERNATIONAL ENGINEERING CONSULTANT JOINT-STOCK COMPANY Vietnam National universities development project – Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Da Nang University subproject (Funded by World Bank) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Ahs Affected Households CC Climate change AC Asphalt concrete CeC Cement concrete CMC Construction monitoring consultant DED Detailed engineering design DOC Department of Construction DOF Department of Finance DONRE Department of Natural Resources and Environment DOT Department of Transport DPI Department of Planning and Investment EE Energy efficiency EIA Environmental impact assessment ESIA Environment and Social Impact Assessment ECOP Environmental Code of Practice EMC External Monitoring Consultant EMP Environmental Management Plan EMS Environmental monitoring system FS Feasibility -

Summary of Evaluation Result

Summary of Evaluation Result 1. Outline of the Project Country: Socialist Republic of Vietnam Project Title: the project on the Villager Support for Sustainable Forest Management in Ventral Highland Issue/ Sector: Natural Environment Cooperation Scheme: Technical Cooperation Project Division in charge: JICA Vietnam office Total Cost: 251 million Yen Period of 3 years and 3 months from June Partner Country’s Implementation Cooperation 20, 2005 to September 19, 2008 Organization: (R/D): (R/D):Signed on April 12, 2005 - Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) - Division of Forestry, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) of Kon Tum province - Kon Tum province Forestry Project Management Board Supporting Organization in Japan: Forestry Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Related Cooperation: None 1-1 Background of the Project The Central Highlands in Vietnam is recognized as higher potential for forestry development because the area sustains large scale natural forest. The development on the forest resources in the area requires enough environmental consideration such as the ecological conservation, social and economical perspectives. This was recognized that the development of the forest resources also requires adequate forest management plan and its project implementation in accordance with the comprehensive development plan. Under those backgrounds, “The Feasibility Study on the Forest Management Plan in the Central Highlands in Socialist Republic of Vietnam” was conducted in Kon Tum Province from January 2000 to December 2002. The study targeted to Kon Plong district in the province. Based on the Forest resource inventory study and management condition of the forest enterprise, target area for the project implementation was identified and master plan for the forest management including plans for silvicultural development and support for villagers were proposed. -

Southeast Asia SIGINT Summary, 4 January 1968

Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 • • • • •• • • •• • • ... • •9 .. • 3/0/STY/R04-68 o4 JAN 68 210oz DIST: O/UT SEA SIGSUM 04-68 THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CODEWORD MATERIAL Declassified and Approved for Release by NSA on 10- 03- 2018 pursuant to E . O. 13526 Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 TOP ~ECll~'f Tltf!rqE 3/0/STY/R04-68 04 Jan 68 210oz DIST: O/UT NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY SOUTHEAST ASIA SIGINT SUMMARY This report summarizes developments noted throughout Southeast Asia available to NSA at time of publication on 04 Jan 68. All information in this report is based entirely on SIGINT except where otherwise specifically indicated. CONTENTS PAGE Situation Summary. ~ . • • 4 • • • • • • • • 1 I. Corrnnunist Southeast Asia Military INon - Responsive IA. I 1. Vietnamese Corrnnunist Corrnnunications South Vietnam. • • • . • . •• . 2 2. DRV Corrnnunications .. ~ . 7 THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS i/11 PAGE(S) TOP ~~GRgf TaINi Doc ID: 6636695 Doc Ref ID: A6636694 TOP ~ECRET TRI~~E 3/0/STY/R04-68 SITUATION SUMMARY In South Vietnam, communications serving elements of the PAVN 2nd Division continue to reflect contact with Allied forces in ..:he luangNam-Quang Tin Province area of Military Region (HR:· : . n;_fficulties in mounting a planned attack on Dak To aLr:-fl.~l<l in Kontum Province were reported to the Military Intelligence Section, PAVN 1st Division by a subordinate on 3 Jan:ic.ry. In eastern Pleiku Province the initial appearance o:f cct,,su.:1icc1.t:ions between a main force unit of PAVN B3 Front and a provincial un:Lt in MR 5 was also noted. -

Development and Climate Change in the Mekong Region Case Studies

Development and Climate Change in the Mekong Region Case Studies edited by Chayanis Kri�asudthacheewa Hap Navy Bui Duc Tinh Saykham Voladet Contents i Development and Climate Change in the Mekong Region ii Development and Climate Change in the Mekong Region Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) SEI is an international non-profit research and policy organization that tackles environment and development challenges. SEI connects science and decision- making to develop solutions for a sustainable future for all. SEI’s approach is highly collaborative: stakeholder involvement is at the heart of our efforts to build capacity, strengthen institutions and equip partners for the long-term. SEI promotes debate and shares knowledge by convening decision-makers, academics and practitioners, and engaging with policy processes, development action and business practice throughout the world. The Asia Centre of SEI, based in Bangkok, focuses on gender and social equity, climate adaptation, reducing disaster risk, water insecurity and integrated water resources management, urbanization, and renewable energy. SEI is an affiliate of Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. SUMERNET Launched in 2005, the Sustainable Mekong Research Network (SUMERNET) brings together a network of research partners working on sustainable development in the countries of the Mekong Region: Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. The network aims to bridge science and policy in the Mekong Region and pursues an evolving agenda in response to environmental issues that arise in the region. In the present phase of its program (2019–27), SUMERNET 4 All, the network is focusing on reducing water insecurity for all, in particular for the poor, marginalized and socially vulnerable groups of women and men in the Mekong Region. -

The Case of Vietnam's Haiphong Water Supply Company

Innovations in Municipal Service Delivery: The Case of Vietnam's Haiphong Water Supply Company by Joyce E. Coffee B.S. Biology; Environmental Studies; Asian Studies Tufts University, 1993 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 21 April 1999 © Joyce Coffee, 1999. All rights reserved perr bepartmedti 'of Uroan Studies and Planning 21 April 1999 Certified by: Paul Smoke Associate Professor of the Practice of Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Associate Professor Paul Smoke Chair, Master in City Planning Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning ROTCHi MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 1 9 1999 LIBRARIES 7 INNOVATIONS IN MUNICIPAL SERVICE DELIVERY: THE CASE OF VIETNAM'S HAIPHONG WATER SUPPLY COMPANY by JOYCE ELENA COFFEE Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on 21 April 1999 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT This thesis describes a state owned municipal water supply service company, the Haiphong Water Supply Company (HPWSCo), that improved its service delivery and successfully transformed itself into a profit making utility with metered consumers willing to pay for improved service. The thesis examines how HPWSCo tackled the typical problems of a developing country's municipal water supply company and succeeded in the eyes of the consumers, the local and national governments, and the wider development community. The thesis describes how and under what conditions HPWSCo has changed itself from a poorly performing utility to a successful one. -

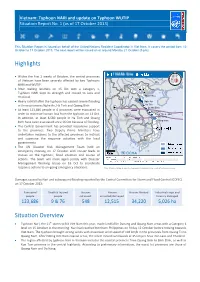

Highlights Situation Overview

Vietnam: Typhoon NARI and update on Typhoon WUTIP Situation Report No. 1 (as of 17 October 2013) This Situation Report is issued on behalf of the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Viet Nam. It covers the period from 12 October to 17 October 2013. The next report will be issued on or around Monday 21 October (5 pm). Highlights Within the first 2 weeks of October, the central provinces of Vietnam have been severely affected by two Typhoons NARI and WUTIP. After making landfalls on 15 Oct with a Category 1, Typhoon NARI kept its strength and moved to Laos and Thailand. Thanh Hoa Heavy rainfall after the typhoon has caused severe flooding Nghe An in three provinces Nghe An, Ha Tinh and Quang Binh Ha Tinh Quang Binh At least 123,686 people in 6 provinces were evacuated in Quang Tri order to minimize human loss from the typhoon on 14 Oct. Thua Thien - Hue In addition, at least 8,580 people in Ha Tinh and Quang Da Nang Binh have been evacuated since 16 Oct because of flooding. Quang Nam The Central Government has provided responsive support to the provinces. Two Deputy Prime Ministers have undertaken missions to the affected provinces to instruct and supervise the response activities with the local governments. The UN Disaster Risk Management Team held an emergency meeting on 17 October with cluster leads to discuss on the typhoon, flood situation and course of actions. The team will meet again jointly with Disaster Management Working Group on 18 Oct to coordinate response actions to on-going emergency situations. -

Has Dyke Development in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta Shifted flood Hazard Downstream?

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 3991–4010, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-3991-2017 © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Has dyke development in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta shifted flood hazard downstream? Nguyen Van Khanh Triet1,4, Nguyen Viet Dung1,4, Hideto Fujii2, Matti Kummu3, Bruno Merz1, and Heiko Apel1 1GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Section 5.4 Hydrology, 14473, Potsdam, Germany 2Faculty of Agriculture, Yamagata University, 1-23 Wakaba-machi, Tsuruoka, Yamagata 997-8555, Japan 3WDRG Water & Development Research Group, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland 4SIWRR Southern Institute of Water Resources Research, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Correspondence to: Nguyen Van Khanh Triet ([email protected]) Received: 4 March 2017 – Discussion started: 6 April 2017 Revised: 26 June 2017 – Accepted: 5 July 2017 – Published: 7 August 2017 Abstract. In the Vietnamese part of the Mekong Delta of 19–32 cm. However, the relative contributions of the three (VMD) the areas with three rice crops per year have been drivers of change vary in space across the delta. In summary, expanded rapidly during the last 15 years. Paddy-rice culti- our study confirms the claims that the high-dyke develop- vation during the flood season has been made possible by im- ment has raised the flood hazard downstream. However, it plementing high-dyke flood defenses and flood control struc- is not the only and not the most important driver of the ob- tures. However, there are widespread claims that the high- served changes. It has to be noted that changes in tidal levels dyke system has increased water levels in downstream areas. -

The Story of New Urban Areas in Can Tho City

Planning for peri-urban development and flooding issues: The story of new urban areas in Can Tho City Group of researchers Dr. Nguyen Ngoc Huy- Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International, MSc. Ky Quang Vinh -Climate Change Coordination Office -CCCO Can Tho, Arch.Nguyen Thi Anh Ngoc- Can Tho City Center for Inspection and Construction Planning, MSc. Tran The Nhu Hiep-Can Tho City Institute of Socio-Economic Development Studies, MSc. LeThu Trang-National University of Civil Engineering, Arch.Tran Kieu Dinh-Can Tho City Association of Architects. 1. Introduction The Mekong Delta (MKD), in which Can Tho City is located, occupies a low-lying region in the center of South Hau River (Bassac River). The MKD is predicted to be one of the three most vulnerable deltas in the world caused by climate change. The topography of the city is flat and low with a height of 0,5-1m above sea level. Along Hau River, national highway 1 and national highway 91, the land raises to a height of 1,0-1,5m above sea level which has developed into the city center. From Hau River, the land is gradually lower in Northeast- Southwest direction. Seasonal flooding is a typical natural characteristic of the MKD and Can Tho City. Rainy season often starts from May to November with highest rainfalls recorded from August to October at the same time of high flow discharge from upstream which annually creates “Mùa nước nổi” (water moving season). “Mùa nước nổi” provides livelihood the benefits of natural aquatic products and transports sediments to the fields, thus act as a natural mechanism of fertility recovery. -

Decision No. 5811QD-Ttg of April 20, 2011, Approving the Master Plan On

Issue nos 04-06/Mtly2011 67 (Cong BaG nos 233-234IAprrI30, 2011) Decision No. 5811QD-TTg of April 20, lifting Kon Tum province from the poverty 2011, approving the master plan on status. socio-economic development of Kon 3. To incrementally complete infrastructure Turn province through 2020 and urbanization: to step up the development of a number of economic zones as a motive force for hoosting the development of difficulty-hit THE PRIME MINISTER areas in the province. Pu rsriant to the Dcccml.cr 25, 2001 Law 011 4. 10 achieve social progress and justice in Organization ofthe Government; each step of development. To pay attention to Pursuant to the Government :\' Decree No 92/ supporti ng deep-lying. remote and ethnic 2006/NDCP of September 7, 2006, Oil the minority areas in comprehensive development; formulatiou, approval and II1(1fWgClIlCllt of to conserve and bring into play the traditional socio-economic del'elopmem master plans and cultures ofethnic groups. Decree No. 04/2008/ND-CP of Januarv 11, 5. To combine socio-economic development 2008, amending and supplementing a number with defense and security maintenance; to firmly ofarticles ofDecree No. 92/2006/ND-C/': defend the national border sovereignty; to firmly At the proposal (if the PeOIJ! e's Committee maintain pol itical security and social order and ofKon Tum province, safety; 10 enhance friendly and cooperative relations within the Vietnam- Laos- Cambodia DECIDES: development triangle. Article I. To approve the master plan on II. DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES soc io-ccrmomic rl('v~lnpnH'nt of Kon Tum province through 2010, with the following I.