ALTOONA HABS No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Thriving Cover Story: Peterman’Sflower Shop Continues Impressive History

December 2019 Still thriving Cover story: Peterman’sFlower Shop continues impressive history ................................PAGES 3 Altoona chiropractors have harmonious goals ................................PAGE 5 Ribbon Cuttings ..........................PAGE 15-16 695-5323 COMMERCIAL OPPORTUNITIES COMMERCIAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR SALE/LEASE - LISTING AGENT MATT DEPAOLIS 814-329-3021 LZe^ hk E^Zl^' Hpg^k ÛgZg\bg` Zg] \hg]h himbhgl #52799 & E>:L>' :iikhqbfZm^er +%,.) lj _m hg ma^ fZbg ZoZbeZ[e^' FZbg [nbe]bg` aZl ZiikhqbfZm^er ,-%-22 l_ e^o^e *%+)) lj _m hg ma^ ehp^k e^o^e' <hfie^m^ k^ghoZmbhg pbma - ehZ]bg` ]h\dl Zg] mph `khng] e^o^e ho^ka^Z] h_ ma^ ^qm^kbhk fZbg e^o^e fZdbg` mabl \eZll : h_Û\^ liZ\^' ]hhkl' <nkk^gm m^gZgm h\\nib^l ZiikhqbfZm^er +%+/+ l_ h_ FZbg e^o^e :=: \hfiebZgm' LaZk^] nl^ h_ Z eZk`^ \hg_^k^g\^ h_Û\^ Zg] +,%+)) l_ h_ pZk^ahnl^ liZ\^' :iikhqbfZm^er *)%1))l_ h_ fZbg [nbe]bg` Zg] *%*.+ bg Z ]^mZ\a^] [nbe]bg` khhf(\eZll khhf' ?ehhkbg` ZeehpZg\^' Ab`a mkZ_Û\ \hngm Zg] \nkk^gmer ngh\\nib^]' K^lb]^gmbZe ngbm hg ma^ l^\hg] Ühhk' ]bk^\m Z\\^ll mh B&22 Km^ ++' <hgmZ\m FZmm =^IZhebl !1*-" <Zee FZmm =^IZhebl !1*-" ,+2&,)+* ,+2&,)+* _hk fhk^ bg_hkfZmbhg Zg] mh l^m ni Z mhnk' 2 Blair County 2 Blair Business Mirror Chamber News www.blairchamber.com Chamber Notes New Members Heading to 2020 with my hair on fire Sometimes the hardest part of writing approved by the Chamber Board of Direc- this column is coming-up with an appro- tors is making the Business Hall of Fame priate title. -

Some Clips May Be Behind a Paywall. If You Need Access to These Clips, Email Me at [email protected]

Some clips may be behind a paywall. If you need access to these clips, email me at [email protected]. Top DEP Stories Pittsburgh Business Times: Marcellus wells in Pennsylvania most productive in U.S http://www.bizjournals.com/pittsburgh/blog/morning-edition/2016/08/marcellus-wells-in- pennsylvania-most-productive.html Mentions Pocono Record: Tourists make a mess of Minisink Park and Brodhead Creek http://www.poconorecord.com/article/20160810/NEWS/160819974 Air Washington Observer Reporter: Paying for Bad Air? http://www.observer-reporter.com/20160814/paying_for_bad_air Press Sun Bulleting: FIRED UP: Pa. incinerator opponents urge action http://www.pressconnects.com/story/news/2016/08/10/pa-incinerator-opponents-urge-action-against- project/88513234/ Conservation & Recreation Allegheny Front: Putting the Spotlight on the Humble Moth http://www.alleghenyfront.org/putting-the-spotlight-on-the-humble-moth/ Pittsburgh Tribune Review: Lily pads vex anglers at Deer Lakes Park http://triblive.com/news/allegheny/10950326-74/lakes-lily-deer Washington Observer Reporter: Wetlands expanding in Washington County http://www.observer-reporter.com/20160812/wetlands_expanding_in_washington_county Pittsburgh Tribune Review: Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh aims to beautify empty lots http://triblive.com/news/allegheny/10928080-74/ura-lots-pittsburgh Energy Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: Pennsylvania’s future depends on clean power http://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2016/08/14/Pennsylvania-s-future-depends-on-clean- power/stories/201608140076 Pittsburgh -

Budget Impact in September, Spring Twp

2017 – 2018 COMMONWEALTH BUDGET These links may expire: January 19 Lawmakers hear state tax proposals HARRISBURG — Pennsylvania lawmakers should consider expanding the base of some state taxes and lowering tax rates in order to address long-standing fiscal issues, several economists told members of a House panel Thursday. That could include making more items subject to the state sales tax and... - Altoona Mirror January 17 All aboard plan to spruce up SEPTA's trolley lines SEPTA’s trolleys haven’t been replaced since the 1980s when Ronald Regan was president, yet they are wildly popular with their 100,000 riders who squeeze into them every day. Thankfully, the transit agency wants to replace them with bigger cars which can handle roughly twice as many... - Philadelphia Inquirer January 16 Legislators outline goals for new year Local legislators look forward to passing bills in the new year, and saying goodbye to the budget woes of 2017. Both Rep. Dan Moul (R-91) and Sen. Rich Alloway II (R-33) were unhappy with the decision to borrow money against future revenue in order to patch the... - Gettysburg Times January 14 Lowman Henry: Pa. budget follies set to resume The last time a Pennsylvania governor signed a full, complete state budget into law was July 10, 2014. Gov. Tom Corbett signed off on that state fiscal plan just days after it was approved by the Legislature, completing a four-year run of on-time state budgets.... - Pittsburgh Tribune-Review January 12 Lawmakers react to governor's opioid state of emergency Local lawmakers said Gov. -

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

20 Under 40 Recipients Since the Program’S Inception in 2007

Following are a list of the Mirror’s 20 Under 40 recipients since the program’s inception in 2007: 2007 RECIPIENT BUSINESS Elsie Zengel Altoona Curve Troy Campbell Altoona First Savings Bank Jess Lattanza St. Francis University Scott Lawhead Hite Company James Parker Blair Medical Associates Jay Young Altoona Mirror Kellie Goodman WTAJ-TV Brian Durbin Durbin Companies Season Consiglio REI Jim Kilmartin Kingdom Solutions Lori Manners Altoona Regional Health Systems Ben Mazur Mazur Media Travis Sheetz Sheetz Erin Johnson Bellwood-Antis School District Devin Mullen Your Jewelry Box Paul Kirby Keller Engineers Phil Kulp Kulp Family Dairy Traci Naugle Hippo & Fleming Law Offices Joe Stevens III Stevens Mortuary Jason Miller Miller & Associates 2008 RECIPIENT BUSINESS Tim Cassidy New Pig Tony DeGol WTAJ-TV Jim Della Reliable Towing Rob Egan Altoona-Johnstown Diocese Eric Irwin Irwin Financial Monica Jones Sheetz Todd Lewis Shoe Fly Shoes Marc McKillop Giant Eagle Jonathan O’Harrow Penn State Altoona Mary Ann Probst Sullivan, Forr, Stokan, Huff, Kormanski Law Amanda Stoehr St. Francis University Darin Tornatore ATC Associates Tara Wood Sanofi-Aventis Phamaceutical Rachel Derby Blair County Respiratory Amanda Barry Altoona Mirror Sarah Piper Hollidaysburg Community Partnership Jeff Garner Altoona Curve Jen Mallad Blair Business Communications Jason Davis Snap Fitness Matt Garber Virtual Office Systems 2009 RECIPIENT BUSINESS Amy Mearkle WTAJ-TV Matthew Fox ABCD Tyke Steiner Hollidaysburg YMCA Jennifer Knisely Altoona Public Library Mike Hofer Central Blair Rec Commission *Matt Vipond Vipond Appliance Sean Burke McQuaide Blasko Law Elizabeth Benjamin Andrews & Beard Law Offices Robert Donlan The Hancock Group Cory Giger Altoona Mirror Derek Miller Advantage Resource Group Becky Crilly Reliance Bank Joe Nyanko JPN Management Inc. -

An Overall Pian for the Development and Preservation of the City of Mooha, Pennsylvania

An Overall Pian for the Development and Preservation of the City of Mooha, Pennsylvania Prepzred Under the Direction of the City of Altoona Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee and Staff of the City of Altoona Depaitmsnt of Planning and Development Adopted by Resolution or' Altoona City CounciI on August 9, 2gOo. Cornm u n it4 Plann i r ia Cons u I t a nt [Jrban Research and Devetoprneilt Corporation Bothle hem, Penns y lva tiia CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................... 1 Great Things Are Happening ................................................... 1 AltoonaWithintheRegion .................................................... 2 I Altoona’sRichHeritage ....................................................... 3 I How This Plan Was Developed ................................................. 4 1 c Initial Public Input ................................................................ 5 Community-Wide Survey ..................................................... 5 Neighborhood Workshops ..................................................... 6 I Results of Focus Group Interviews .............................................. 9 Mission Statement .......................................................... 11 Direction: The Major Goals of this Plan ......................................... 11 I Relationships Between the Components of this Plan ............................... 13 I Land Use and Housing Plan ....................................................... 15 L Economic Development and Downtown Plan -

Community Health Needs Assessment Community Health Strategic Plan Bedford and Blair Counties

Community Health Needs Assessment Community Health Strategic Plan Bedford and Blair Counties June 30, 2019 Enhancing the Health of Our Communities Bedford and Blair Counties COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT UPDATE COVERING UPMC BEDFORD UPMC ALTOONA Table of Contents Introduction Regional Progress Report: 2016 – 2019 . Page 1 I. Executive Summary................................................................Page 4 II. Overview and Methods Used to Conduct the Community Health Needs Assessment .........Page 8 III. Results of the Community Health Needs Assessment and In-Depth Community Profile .......Page 14 IV. UPMC Hospitals: Community Health Improvement Progress and Plans .....................Page 28 2016 – 2019 Progress Reports and 2019 – 2022 Implementation Plans by Hospital UPMC Bedford . Page 26 UPMC Altoona . Page 35 V. Appendices.......................................................................Page 45 Appendix A: Secondary Data Sources and Analysis . Page 46 Appendix B: Detailed Community Health Needs Profile . Page 48 Appendix C: Input from Persons Representing the Broad Interests of the Community . Page 51 Appendix D: Concept Mapping . Page 56 Appendix E: Healthy Blair County Coalition: Community Health Needs Assessment and Implementation Plan . Page 60 2016-2019 UPMC is stepping forward to help our neighbors in Bedford and Blair counties by offering REGIONAL programs and services to improve health and PROGRESS REPORT quality of life in our communities . PROVIDING LOCAL ACCESS TO NATIONALLY • Caring for More Patients with Telemedicine: Founded in 2013, the RANKED, WORLD-CLASS CARE UPMC Bedford Teleconsult Center is a multi-specialty outpatient clinic that uses advances in technology to connect patients with UPMC is taking steps to make health care more convenient for those specialists. From 2013 to 2017, the UPMC Bedford Teleconsult we serve. -

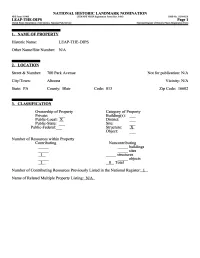

LEAP-THE-DIPS Other Name/Site Number: N/A

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LEAP-THE-DIPS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: LEAP-THE-DIPS Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 700 Park Avenue Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Altoona Vicinity: N/A State: PA County: Blair Code: 013 Zip Code: 16602 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): __ Public-Local: X District: __ Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal:__ Structure: X Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ ___ buildings ___ ___ sites __1_ ___ structures objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LEAP-THE-DIPS Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

B-1 John W Barriger III Papers Finalwpref.Rtf

A Guide to the John W. Barriger III Papers in the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library A Special Collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis This project was made possible by a generous grant From the National Historical Publications and Record Commission an agency of the National Archives and Records Administration and by the support of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis © 1997 The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association i Preface and Acknowledgements This finding aid represents the fruition of years of effort in arranging and describing the papers of John W. Barriger III, one of this century’s most distinguished railroad executives. It will serve the needs of scholars for many years to come, guiding them through an extraordinary body of papers documenting the world of railroading in the first two-thirds of this century across all of North America. In every endeavor, there are individuals for whom the scope of their involvement and the depth of their participation makes them a unique participant in events of historical importance. Such was the case with John Walker Barriger III (1899-1976), whose many significant roles in the American railroad industry over almost a half century from the 1920s into the 1970s not only made him one of this century’s most important railroad executives, but which also permitted him to participate in and witness at close hand the enormous changes which took place in railroading over the course of his career. For many men, simply to participate in the decisions and events such as were part of John Barriger’s life would have been enough. -

Rite Aid / Subway

OFFERING MEMORANDUM RITE AID / SUBWAY 3106 EAST PLEASANT VALLEY BLVD | ALTOONA (BELLWOOD) , PA 16601 EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY: TABLE OF MATTHEW GORMAN CONTENTS +1 484 567 2340 [email protected] 04 TENANT OVERVIEW MICHAEL SHOVER +1 484 567 2344 06 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS [email protected] Property Highlights Financial Overview Investment Overview THOMAS FINNEGAN +1 484 567 2375 PROPERTY SUMMARY [email protected] 10 Property Photos Aerial Map Location Overview ROBERT THOMPSON Local/Regional Map +1 484 567 3341 Demographics [email protected] © 2017© 2019 CBRE, CBRE, INC. INC.ALL RIGHTS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. RESERVED. VIEW PROPERTY VIDEO TENANT OVERVIEW RITE AID / SUBWAY | ALTOONA, PA TENANT OVERVIEW TENANT OVERVIEW FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PROPERTY SUMMARY FINANCIAL ANALYSIS TENANT OVERVIEW Rite Aid is the largest drugstore chain on the East Coast and the third-largest Subway is a privately held American fast food restaurant franchise that in the United States, employing roughly 89,000 associates. The company primarily serves submarine sandwiches and salads. Subway is one of operates retail drugstores which sell prescription drugs, as well as front- the fastest-growing franchises in the world and, as of June 2017, has end products including over-the-counter medications, health and beauty approximately 44,000 stores located in more than 112 countries. It world's aids, personal care items, cosmetics, household items, convenience foods, largest restaurant chain, serving 7 million made-to-order sandwiches a day. greeting cards, and seasonal merchandise. As of Dec 2, 2017, Rite Aid Founded more than 52 years ago, Subway is still a family-owned business, operated 4,404 stores in 31 states and the District of Columbia. -

Inside Corridor

A Newsletter from the Altoona-Blair County Development Corp. Inside the Corridor september | 2009 Two New Manufacturers Decide on In this Issue: Blair County page 1 On July 10, 2009, Governor Edward Rendell was on > Two New Companies hand to announce that a flexible film manufacturer and for Blair County a secondary aluminum recycling operation will locate their new facilities in Blair County, bringing 185 jobs page 2 within the next three years. > PSU-Altoona Announces Diversapack, LLC, a manufacturer and printer of flex- New Railroad Degree ible films will locate in Tyrone, PA’s Jubelirer Business Park and Advanced Metals Processing, LLC, a sec- > Workshop: Funding Governor Ed Rendell welcoming Advanced Metal Processing and Diversapack to Blair County. Energy Efficiency ondary aluminum recycling business will be in the DeGol Industrial Center located in Hollidaysburg, PA. > Blair County Updates Combined, these projects represent total project costs of over $24 million; the creation of 185 new jobs; an page 3 estimated payroll impact of over $7 million and pro- > DSI & ITI Expansion jected benefits packages of over $1.9 million. Borough Council; PA Dept. of Environmental Protection; “We consider our collaborative efforts for economic > Gateway Enhancement Southern Alleghenies Planning & Development development here at ABCD Corp. an item of great pride Project Gains Support Commission. and we are excited to be part of these projects.” said page 4 Martin Marasco, President and CEO of ABCD Corp. In addition, the AMP project would not have been pos- “We are grateful to Diversapack and Advanced Metal sible without the support of the U.S. -

Sam's Club Operates 597 Membership Warehouse Clubs in 44 U.S

1 Absolute NNN Lease Investment Opportunity 2500 W Plank Rd | Altoona, PA 16601 Actual Property Image EXCLUSIVELY MARKETED BY: 2 MAX FREEDMAN Lic. # 644481 512.766.2711 | DIRECT [email protected] 2101 S IH 35, Suite 402 Austin, TX 78741 CHRIS SANDS JENNIFER STEIN 844.4.SIG.NNN Lic. # 93103 Lic. # RM422728 www.SIGnnn.com 310.870.3282 | DIRECT 213.446.5366 | DIRECT In Cooperation with JDS Real Estate Services – Lic # RB068057 [email protected] [email protected] © 2018 Sands Investment Group (SIG). The information contained in this ‘Offering Memorandum,’ has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Sands Investment Group does not doubt its accuracy, however, Sands Investment Group makes no guarantee, representation or warranty about the accuracy contained herein. It is the responsibility of each individual to conduct thorough due diligence on any and all information that is passed on about the property to determine it’s accuracy and completeness. Any and all projections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are used to help determine a potential overview on the property, however there is no guarantee or assurance these projections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are subject to change with property and market conditions. Sands Investment Group encourages all potential interested buyers to seek advice from your tax, financial and legal advisors before making any real estate purchase and transaction. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Sam’s Club | 2500 W Plank RD | Altoona, PA 16601 Investment Overview Investment Summary Investment Highlights Area Overview Location Map Retail Map Demographics City Overview Tenant Overview Tenant Profile Lease Abstract Lease Summary Rent Roll INVESTMENT OVERVIEW 4 INVESTMENT SUMMARY 5 Sands Investment Group is pleased to present for sale the Sam’s Club located at 2500 W Plank Road in Altoona, Pennsylvania.