Learning from Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Seafood Industry Association Et Al (PDF

- Joint submission to the Productivity Commission Issues Paper Barriers to Effective Climate Change Adaptation Joint submission prepared by - Perez, E., Jenkins, H., Price, L., Donnelly, R., & Conn, W. (2011) for the Queensland Seafood Industry Association, Australian Prawn Farmers Association, Oceanwatch Australia and Pro-vision Reef. Acknowledgements The Queensland Seafood Industry Association (QSIA) has actively engaged in helping to facilitate a better understanding of climate change issues at a State and National level. This submission demonstrates the ongoing positive relationship between sectors of industry to help identify the barriers to climate change adaption in the context of fisheries and conservation management. The issues are complicated and require joint industry and government solutions. The QSIA wishes to thank Helen Jenkins (Executive Officer, Australian Prawn Farmers Association), Lowri Pryce (Executive Officer, Oceanwatch), Ryan Donnelly (Pro-Vision Reef) and Wil Conn (Industry Recovery Officer – Cyclone Yasi, Seafood and Aquaculture Industries) for their contributions to this submission. The QSIA would also like to thank industry and researcher contributions to earlier versions of the submission 1. 1 The QSIA appreciates the images provided by Richard Fitzpatrick and the Australian Prawn Farmers Association. 2 CCContentsContents 1. Introduction 4-5 1.1. Queensland Seafood Industry Association 1.2. Australia Prawn Farmers Association 1.3. Oceanwatch Australia 1.4. Pro-vision Reef 1.5. Submission Structure 2. Background 6-7 2.1. Industry Structure 2.2. Need to Engage on the Climate Change Issue 3. Key Issues 8-27 3.1. Uncertainty 3.2. Barriers 3.3. Regulatory Reforms 3.4. Insurance Markets 3.5. Regulation 3.6. Government Provision of Public Goods 3.7. -

Effects of Cyclone-Generated Disturbance on a Tropical Reef Foraminifera Assemblage Received: 12 November 2015 Luke C

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Effects of cyclone-generated disturbance on a tropical reef foraminifera assemblage Received: 12 November 2015 Luke C. Strotz1, Briony L. Mamo2 & Dale Dominey-Howes3 Accepted: 05 April 2016 The sedimentary record, and associated micropalaeontological proxies, is one tool that has been Published: 29 April 2016 employed to quantify a region’s tropical cyclone history. Doing so has largely relied on the identification of allochthonous deposits (sediments and microfossils), sourced from deeper water and entrained by tropical cyclone waves and currents, in a shallow-water or terrestrial setting. In this study, we examine microfossil assemblages before and after a known tropical cyclone event (Cyclone Hamish) with the aim to better resolve the characteristics of this known signal. Our results identify no allochthonous material associated with Cyclone Hamish. Instead, using a swathe of statistical tools typical of ecological studies but rarely employed in the geosciences, we identify new, previously unidentified, signal types. These signals include a homogenising effect, with the level of differentiation between sample sites greatly reduced immediately following Cyclone Hamish, and discernible shifts in assemblage diversity. In the subsequent years following Hamish, the surface assemblage returns to its pre-cyclone form, but results imply that it is unlikely the community ever reaches steady state. Tropical reef systems are important refugia for biodiversity, harbouring an array of critical and charismatic taxa, and have both significant cultural and economic value1. The high-intensity winds, waves, torrential rains, and flooding associated with tropical cyclone events result in high levels of damage to tropical reef communities2,3 through direct physical destruction4,5 and increased sediment input and suspended sediment residence times6–8. -

Vision and Transition Strategy for A

Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth CRCWSC Integrated Research Project 1: Water Sensitive City Visions and Transition Strategies 2 | Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth IRP1 WSC Visions and Transition Strategies IRP1-4-2018 Authors Katie Hammer1,2, Briony Rogers1,2, Chris Chesterfield2 1 School of Social Sciences, Monash University 2 CRC for Water Sensitive Cities © 2018 Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities Ltd. This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. Publisher Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities Level 1, 8 Scenic Blvd, Clayton Campus Monash University Clayton, VIC 3800 p. +61 3 9902 4985 e. [email protected] w. www.watersensitivecities.org.au Date of publication: August 2018 An appropriate citation for this document is: Hammer, K., Rogers, B.C., Chesterfield, C. (2018) Vision and Transition Strategy for a Water Sensitive Greater Perth. Melbourne, Australia: Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities. This report builds directly on “Shaping Perth as a Water Sensitive City: Outcomes and perspectives from a participatory process to develop a vision and strategic transition framework”, which was the output of a precursor CRCWSC project, A4.2 Mapping water sensitive city scenarios. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the Water Sensitive Transition Network for their ongoing enthusiasm and commitment to the water sensitive city agenda in Perth. -

Extreme Natural Events and Effects on Tourism: Central Eastern Coast of Australia

EXTREME NATURAL EVENTS AND EFFECTS ON TOURISM Central Eastern Coast of Australia Alison Specht Central Eastern Coast of Australia Technical Reports The technical report series present data and its analysis, meta-studies and conceptual studies, and are considered to be of value to industry, government and researchers. Unlike the Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre’s Monograph series, these reports have not been subjected to an external peer review process. As such, the scientific accuracy and merit of the research reported here is the responsibility of the authors, who should be contacted for clarification of any content. Author contact details are at the back of this report. National Library of Australia Cataloguing in Publication Data Specht, Alison. Extreme natural events and effects on tourism [electronic resource]: central eastern coast of Australia. Bibliography. ISBN 9781920965907. 1. Natural disasters—New South Wales. 2. Natural disasters—Queensland, South-eastern. 3. Tourism—New South Wales—North Coast. 4. Tourism—Queensland, South-eastern. 5. Climatic changes—New South Wales— North Coast. 6. Climatic changes—Queensland, South-eastern. 7. Climatic changes—Economic aspects—New South Wales—North Coast. 8. Climatic changes—Economic aspects—Queensland, South-eastern. 632.10994 Copyright © CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd 2008 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Any enquiries should be directed to: General Manager Communications and Industry Extension, Amber Brown, [[email protected]] or Publishing Manager, Brooke Pickering [[email protected]]. -

In the Aftermath of Cyclone Yasi: AIR Damage Survey Observations

AIRCURRENTS By IN THE AFTERMATH OF CYCLONE YaSI: AIR DAMAGE SURVEY OBSERVATIONS EDITOR’S NOTE: In the days following Yasi’s landfall, AIR’s post-disaster survey team visited areas in Queensland affected by the storm. This article 03.2011 presents their findings. By Dr. Kyle Butler and Dr. Vineet Jain Edited by Virginia Foley INTRODUCTION Severe Cyclone Yasi began as a westward-moving depression In addition to the intense winds, Yasi brought 200-300 off Fiji that rapidly developed into a tropical storm before millimeters of precipitation in a 24 hour period and a storm dawn on January 30, 2011. Hours later, Yasi blew across the surge as high as five meters near Mission Beach. northern islands of Vanuatu, continuing to grow in intensity and size and prompting the evacuation of more than 30,000 residents in Queensland, Australia. By February 2 (local time), the storm had achieved Category 5 status on the Australian cyclone scale (a strong Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale). At its greatest extent, the storm spanned 650 kilometers. By the next day, it became clear that Yasi would spare central Queensland, which had been devastated by heavy flooding in December. But there was little else in the way of good news. Yasi made landfall on the northeast coast of Queensland on February 3 between Innisfail and Cardwell with recorded gusts of 185 km/h. Satellite-derived sustained Figure 1. Satellite-derived 10-minute sustained wind speeds in knots just after wind speeds of 200 km/h were estimated near the center Cyclone Yasi made landfall. -

Cyclone Hamish on One Tree Island – Information from In-Situ Sensor Data

The Impact of Cyclone Hamish on One Tree Island – information from in-situ sensor data Scott Bainbridge, Damian Eggeling, Gavin Feather Australian Institute of Marine Science Track of Cyclone Hamish 6th March, 4am 7th March, 4am 8th March, 4am 9th March, 4am 10th March, 4am NOAA Satellite Image – 9th March 2009 Wind Speed Categories Wind KPH Knots M/Sec Category Gale Force >62 >33 >17 Destructive >89 >48 >25 Cyclonic >117 >63 >32 Source: BoM web site Cyclone Map for 9th March 2009 One Tree Island Source: BoM web site Cyclone report 4pm 9th March A Cyclone WARNING remains current for coastal and island communities from Yeppoon to Hervey Bay. A Cyclone WATCH remains current for coastal and island communities from Hervey Bay to Tewantin. Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish, a CATEGORY 4 CYCLONE, is located off the Capricornia coast and at 4:00 pm EST was estimated to be 255 kilometres east of Yeppoon and 245 kilometres north northeast of Bundaberg, moving southeast at 17 kilometres per hour. Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish poses a threat to exposed coastal and island communities between Yeppoon and Hervey Bay [including Heron, Fraser and Lady Elliot Islands]. The cyclone is expected to maintain a southeast track parallel to the coast during the next 24 hours. In the 24 to 48 hour period the cyclone is expected to become slow moving and weaken slightly. Details of Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish at 4:00 pm EST: .Centre located near...... 22.8 degrees South 153.2 degrees East .Location accuracy........ within 28 kilometres .Recent movement.......... towards the southeast at 17 kilometres per hour .Wind gusts near centre.. -

Local Disaster Management Plan (LDMP) Has Been Prepared to Ensure There Is a Consistant Approach to Diaster Management in the Livingstone Shire

F Document Set ID: 8554803 Version: 1, Version Date: 17/09/2020 FOREWORD Foreword by the Chair, Andrew Ireland of the Livingstone Shire Local Disaster Management Group. The Livingstone Shire Local Disaster Management Plan (LDMP) has been prepared to ensure there is a consistant approach to Diaster Management in the Livingstone Shire. This plan is an important tool for managing potential disasters and is a demonstrated commitment towards enhancing the safety of the Livingstone Shire community. The plan identifies potential hazards and risks in the area, identifies steps to mitigate these risks and includes strategies to enact should a hazard impact and cause a disaster. This plan has been developed to be consistant with the Disaster Management Standards and Guidelines and importantly to intergrate into the Queensland Disaster Management Arrangements (QDMA). The primary focus is to help reduce the potential adverse effect of an event by conducting activities before, during or after to help reduce loss of human life, illness or injury to humans, property loss or damage, or damage to the environment. I am confident the LDMP provides a comprehensive framework for our community, and all residents and vistors to our region can feel secure that all agenices involved in the Livingstone Shire LDMP are dedicated and capable with a shared responsibility in disaster management. On behalf of the Livingstone Shire Local Disaster Management Group, I would like to thank you for taking the time to read this important plan. Livingstone Shire Council Mayor Andrew Ireland Chair, Local Disaster Management Group Dated: 26 August 2020 Page 2 of 175 ECM # xxxxxx Version 6 Document Set ID: 8554803 Version: 1, Version Date: 17/09/2020 ENDORSEMENT This Local Disaster Management Plan (LDMP) has been prepared by the Livingstone Shire Local Disaster Management Group for the Livingstone Shire Council as required under section 57 of the Disaster Management Act 2003 (the Act). -

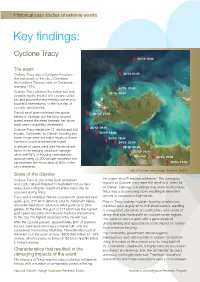

Cyclone Tracey-Key Findings.Pdf

Historical case studies of extreme events Key findings: Cyclone Tracy 22/12-15:30 The event Cyclone Tracy was a Category 4 cyclone 22/12-21:00 that laid waste to the city of Darwin in the Northern Territory early on Christmas morning 1974. 23/12- 01:30 Cyclone Tracy showed the nation just how 23/12- 09:00 devastating the impact of a cyclone could be, and awoke the engineering community, local and international, to the true risk of cyclonic wind storms. Tracy’s small size minimised the spatial 23/12- 21:00 extent of damage, but her slow forward speed meant the areas beneath her storm track were completely devastated. 24/12- 09:00 Cyclone Tracy resulted in 71 deaths and 650 injuries. Fortunately for Darwin, flooding and 24/12- 13:00 storm surge were not major issues or these 24/12- 18:30 numbers could have been far higher. 24/12- 21:00 In almost all cases wind was the dominant 25/12- 00:30 factor in the ensuing structural damage, 25/12- 03:00 which left 94% of housing uninhabitable, Darwin approximately 40,000 people homeless and 25/12- 09:00 necessitated the evacuation of 80% of the 25/12- 12:00 city’s residents. Path of Cyclone Tracy. Image: Matthew Mason Scale of the disaster Cyclone Tracy is one of the most prominent the region since European settlement. The damaging and costly natural disasters in Australia’s history. Very impacts of Cyclone Tracy were the result of a ‘direct hit’ rarely does a disaster impact an entire major city, as on Darwin. -

Street Tree Master Plan Version 2 - September 2005

City of Wanneroo Street Tree Master Plan Version 2 - September 2005 Version No. Detail List of Revisions Date Authorised by Version 1 - Aug’04 As Presented by Arbor Vitae 10 August Council and approved by Council 2004 Version 2 - Sept’05 Full Internal Review - As • Addition of List of Common Names (Appendix C) September Council/Rob K adopted at City of Wanneroo • Addition of the following tree species: 2005/August Council Meeting held on 20 1. Brachychiton gregorii 2006 September 2005 2. Callistemon “Kings Park Special” 3. Eucalyptus melliodora 4. Eucalyptus “torwood” 5. Liquidambar styraciflua 6. Melaleuca ericifolia 7. Prunus x blireana 8. Pyrus calleryana Includes revisions to Landscape Character Unit Tree Lists and Appendix D (formerly Appendix C) Plant Information Fact Sheets. • Modifications to Plant Information Fact Sheets including additional photos, more information on longevity, and amendments to the following: Olea europea (more information), correction of all “Headings” formerly spelt “Habitat” to “Habit” and spelling correction to Araucaria heterophylla. • Reference to “City of Wanneroo Recommended Climber Groundcover and Shrub Species list in Executive Summary and Appendix E. • Modification to Figure 26 – More Fire Resistant native trees. Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Requirements of Trees, the Public and the City of Wanneroo.............................................................................................................7 -

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Thursday, 27 October 2011 SPEAKER’S RULING ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3473 Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by the Minister for Main Roads and the Minister for Education .................... 3473 PETITIONS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3474 MINISTERIAL PAPERS ................................................................................................................................................................. 3474 Members’ Daily Travelling Allowance Claims; Travel Benefits for Former Members of the Legislative Assembly ............ 3474 Tabled paper: Daily travelling allowance claims by members of the Legislative Assembly— Annual Report 2010-11. ......................................................................................................................................... 3474 Tabled paper: Travel benefits afforded former members of the Legislative Assembly— Annual Report 2010-11. ........................................................................................................................................ -

Classification of Arid & Semi-Arid Areas

Classification of Arid & Semi-Arid Areas: A Case Study in Western Australia Guy Leech Abstract Arid and semi-arid environments present challenges for ecosystems and the human activities within them. Climate classifications are one method of understanding the climate of these regions, giving regional- scale insight into parameters such as temperature and precipitation. This essay qualitatively compares the application of four different climate classification schemes (Köppen-Trewartha, Guetter-Kutzbach, De Martonne and Erinç) to a transect across Western Australia. The classification schemes show a distinct climatic gradient from the wet coast to the dry continental interior, with the most pronounced gradient located near the coast. Strong agreement is found between weather stations and classifications for wet and dry years, indicating that the weather systems on the coast also govern weather inland. Historically wet and dry periods, as well as long-term drying trends were also identified for the coastal regions, which could affect the livelihoods of many people. A long-term drying trend is also evident at Kalgoorlie- Boulder, the most arid, inland town. These results show that climate classifications can identify major trends and shifts in climate on a decadal or yearly basis, and it is hoped that they will become more widely used for this form of analysis. Introduction Arid and semi-arid environments make up a large portion of the Earth’s surface (Figure 1), and present challenges for human ecosystems located within them. These regions are generally defined as having low average rainfall, often associated with high temperatures, which impose fundamental limits on animal and plant populations, and on human activities such as agriculture (CSIRO 2011, Ludwig & Asseng 2006, Ribot et al. -

Australasian Record and Advent World Survey �44

Australasian Record and Advent World Survey 44 Publication of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the Australasian Division VOL. 87, NO. 27 July 5, 1982 VOICE IN THE NIGHT VIC FRANCIS, in the New Zealand Challenge Weekly CONCENTRATED prayer on sea and land resulted in the rescue of four Adventists who drifted in stormy seas for more than four days after their yacht Wiremu sank on Good Friday. While the four Aucklanders—Eric and Winsome Hanna, their son Doug and friend Les Reynolds—prayed as they drifted on a tiny liferaft, members of the Orewa Seventh-day Adventist church joined together to pray for their safety. And those prayers for deliverance were answered, according to Mr. Hanna, when an Air Force Orion spotted three flares they set off and organised rescue procedures. Mr. Hanna says the four people prayed for long periods as they floated and were always confident on being rescued. And he says the experience on the raft—they were thrown out four times the first night and yet managed to hang on—has enriched his Christian experience. "We had a real spiritual experience on that raft," he says. "When you have a five-foot raft with four people on it for four days and nights and you hardly sleep there is a lot of soul searching. INSIDE: "You realise how little you are and how little Eric and Winsome Hanna, surrounded by ■ you do for God. I realised what I could have members of their family and church who In Touch With the been doing instead of galavanting around the prayed for their safe return throughout the President, page 2.