An Analysis of the Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970 and the Ethical and Professional Responsibilities Facing Editors in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75Th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 349 622 CS 507 969 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992). Part XV: The Newspaper Business. INSTITUTION Seneca Nation Educational Foundation, Salamanca, N.Y. PUB DATE Aug 92 NOTE 324p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 507 955-970. For 1991 Proceedings, see ED 340 045. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Business Administration; *Economic Factors; *Employer Employee Relationship; Foreign Countries; Journalism History; Marketing; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; *Newspapers; Ownership; *Publishing Industry; Trend Analysis IDENTIFIERS *Business Media Relationship; Indiana; Newspaper Circulation ABSTRACT The Newspaper Business section of the proceedings contains the following 13 papers: "Daily Newspaper Market Structure, Concentration and Competition" (Stephen Lacy and Lucinda Davenport); "Who's Making the News? Changing Demographics of Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Race, Gender and White Male Backlash in Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Race and the Politics of Promotion in Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Future of Daily Newspapers: A Q-Study of Indiana Newspeople and Subscribers" (Mark Popovich and Deborah Reed); "The Relationship between Daily and Weekly Newspaper Penetration in Non-Metropolitan Areas" (Stephen Lacy and Shikha Dalmia); "Employee Ownership at Milwaukee and Cincinnati: A Study in Success and -

UA68/13/5 the Fourth Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Student Organizations WKU Archives Records Fall 1983 UA68/13/5 The ourF th Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1 Sigma Delta Chi Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_org Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Sigma Delta Chi, "UA68/13/5 The ourF th Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1" (1983). Student Organizations. Paper 141. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_org/141 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Organizations by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ~~ARCH1Vj.~ Fou rth Estaf1!'-' - k .- Vol. a No.1 FJII,1983 l'ubllaIMd by the Western Kentu,ky Unlyer~ty chapter of The Society of Profenionlol J ou rnlollJu, Slim", Deltl Chi 80,..lInl Green, Ky. 42101 Photojournalists document Mor~~ By JAN WI11IERSPOON MORGANTOWN - Back in side the former H and R Block building, behind. tax fonns and carpeting, behind the unassuming facade of U.S. tax bureaucracy, lurks paranoia. The pressure is waiting, hovering arOlmd students as they come into the empty bulldlng and begin a .....end of intense learning and work. Western's Sixth Annual PhototIraphy Workshop began here. Jack Com, workshop diJ"ec. tor, assembled the faculty, which included: -C. Thomas Hardin, chief photo editor and director of photography for The Courier -. Journal and The Louisv:ille Gary Halrlson, a Henderson senior, shoots his subject at Logansport grocery. Times. - Jay Dickman, 1983 - Michael Morse, Western formerly with the Dallas Prophoto of Nashville. -

“READ YOU MUTT!” the Life and Times of Tom Burns, the Most Arrested Man in Portland

OHS digital no. bb OHS digital no. OREGON VOICES 007 “READ YOU MUTT!” 24 The Life and Times of Tom Burns, the Most Arrested Man in Portland by Peter Sleeth TOM BURNS BURST onto the Port- of Liverpool to his death in Southeast land scene in 10, out of curiosity, Portland, Burns lived a life devoted and stayed, he said, for the weather.1 A to improving the lives of the working loner and iconoclast, Burns found his class. way into virtually every major orga- Historians frequently mention nized social movement in his time. Burns’s involvement in Portland’s In his eighty-one years, from England labor movement, but his life has never to Oregon, Burns lived the life of a been explored in detail. From his free-wheeling radical, a colorful street- friendships with lawyer and author corner exhorter whose concern for the C.E.S. Wood to his alliance with femi- working stiff animated his life. His nist and anarchist Dr. Marie Equi, his story is full of contradictions. Burns name runs through the currents of noted having been a friend to famous the city’s labor history. Newspapers communist John Reed prior to the of the day — as well as Burns himself Russian Revolution, but he despised — called him The Most Arrested Man the Communist Party.2 Although in Portland, the Mayor of Burnside, he described himself as a Socialist, and Burns of Burnside. His watch and was what we could call a secular shop on the 200 block of W. Burnside Reporter Fred Lockley dropped by Tom Burns’s book shop on a winter’s night in humanist today, Burns was also briefly was a focal point for radical meetings 1914: “The air was blue with tobacco smoke and vibrant with the earnest voices of involved in a publishing venture with that included luminaries of Portland’s several men discussing the conspiracies of capital” (Oregon Journal, February 22, the former Grand Dragon of the literary, political, and labor landscape. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

The American Newsroom: a Social History, 1920 to 1960

The American Newsroom: A Social History, 1920 to 1960 Will T. Mari A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee Richard Kielbowicz Randy Beam Doug Underwood Program Authorized to Offer Degree Communication © Copyright 2016 Will Mari University of Washington Abstract The American Newsroom: A Social History, 1920 to 1960 Will Mari Chair of the Supervisory Committee Richard Kielbowicz, associate professor, communication Dept. of Communication One of the most important centering places in American journalism remains the newsroom, the heart of the occupation’s vocational community since the middle of the nineteenth century. It is where journalists have engaged with their work practices, been changed by them, and helped to shape them. This dissertation is a thematic social history of the American newsroom. Using memoirs, trade journals, textbooks and archival material, it explores how newsrooms in the United States evolved during a formative moment for American journalism and its workers, from the conclusion of the First World War through the 1950s, the Cold War, and the ascendancy of broadcast journalism, but prior to the computerization of the newsroom. It examines the interior work culture of news workers “within” their newsroom space at large, metropolitan daily newspapers. It investigates how space and ideas of labor transformed the ideology of the newsroom. It argues that news workers were neither passive nor predestinated in how they formed their workplace. Finally, it also examines how technology and unionization affected the newsroom and news workers, and thus charts the evolution of the newsroom in the early-to-middle decades of the twentieth century. -

Document Resume Ed 300 932 Ec 211 076 Title Aids

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 932 EC 211 076 TITLE AIDS Issues (Part 1). Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress, First Session (March 10 1987--Cost and Availability of AZT; April 27, 1987--AIDS and Minorities; September 22, 1987--AIDS Research and Education). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Energy and Commerce. PUB DATE Sep 87 NOTE 280p.; Serial No. 100-68. Portions contain small/marginally legible print. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; *Diseases; *Drug Therapy; Outcomes of Treatment; *Public Health; *Special Health Problems IDENTIFIERS AZT (Drug) ABSTRACT The texts of three nearings on issues connected with AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) are recorded in this document. The first hearing concerne,' the availability and cost of the drug azidothymidine (AZT) for v,c.ims of the disease and considered such questions as what a fair price for AZT is, who will pay for people currently being treated free, who will pay for people after the drug is approved, who is responsible for people who cannot pay. The second hearing (which was held in Houston, Texas) was designed to bring public attention to the disproportionate dangers that AIDS poses for minorities in America--an issue that has been largely unaddressed. The purpose of the third hearing was to build on the already established public acceptance of the need for AIDS education and research by securing adequate and speedy government support for this work. -

The Oregon Journal of Orthopaedics

OJO The Oregon Journal of Orthopaedics Volume II May 2013 JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT BIOMET KNEE IMPLANTS COULDN’T GET ANY BETTER. THE INDUSTRY’S ONLY LIFETIME KNEE IMPLANT REPLACEMENT WARRANTY† IN THE U.S. This’ll make you feel good. Every Oxford® Partial Knee used with Signature™* technology now comes with Biomet’s Lifetime Knee Implant Replacement Warranty.† It’s the first knee replacement warranty† of its kind in the U.S. – and just one more reason to choose a partial knee from Biomet. Other reasons include a faster recovery with less pain and more natural motion.** And now, the Oxford® is available with Signature™ personalized implant positioning for a solution that’s just for you. Who knew a partial knee could offer so much? ® 800.851.1661 I oxfordknee.com Risk Information: Not all patients are candidates for partial knee replacement. Only your orthopedic surgeon can tell you if you’re a candidate for joint replacement surgery, and if so, which implant is right for your specific needs. You should discuss your condition and treatment options with your surgeon. The Oxford® Meniscal Partial Knee is intended for use in individuals with osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis limited to the medial compartment of the knee and is intended to be implanted with bone cement. Potential risks include, but are not limited to, loosening, dislocation, fracture, wear, and infection, any of which can require additional surgery. For additional information on the Oxford® knee and the Signature™ system, including risks and warnings, talk to your surgeon and see the full patient risk information on oxfordknee.com and http://www.biomet.com/orthopedics/getFile.cfm?id=2287&rt=inline or call 1-800-851-1661. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

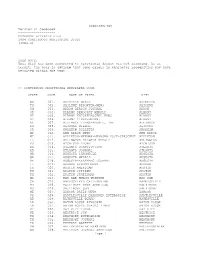

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 19-643 Released: July 11, 2019 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS TO TRANSFER CONTROL OF COX RADIO, INC., TO TERRIER MEDIA BUYER, INC., AND PERMIT-BUT- DISCLOSE EX PARTE STATUS FOR THE PROCEEDING MB Docket No. 19-197 Petition to Deny Date: August 12, 2019 Opposition Date: August 22, 2019 Reply Date: August 29, 2019 On July 2, 2019, Terrier Media Buyer, Inc. (Terrier Media), Cox Radio, Inc. (Cox Radio), and Cox Enterprises, Inc. (Cox Parent) (jointly, the Applicants) filed applications with the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) seeking consent to the transfer of control of Commission licenses (Transfer Application). Applicants seek consent for Terrier Media to acquire control of Cox Radio’s 50 full-power AM and FM radio stations and associated FM translator and FM booster stations.1 As part of the proposed transaction, and in order to comply with the Commission’s local radio ownership rules,2 Cox has sought Commission consent to assign the licenses of Tampa market station WSUN(FM), Holiday, Florida, and Orlando market station WPYO(FM), Maitland, Florida, to CXR Radio, LLC, a divestiture trust created for the purpose of holding those stations’ licenses and other assets.3 1 A list of the Applications can be found in the Attachment to this Public Notice. Copies of the Applications are available in the Commission’s Consolidated Database System (CDBS). Pursuant to the proposed transaction, Terrier also is acquiring Cox’s national advertising representation business and Cox’s Washington, DC news bureau operation. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM