Wolfgang Mozart Oboe Concerto in C Major, K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

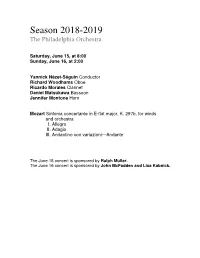

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Radio 3 Listings for 3 – 9 May 2008 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 03 MAY 2008 SUNDAY 04 MAY 2008 to Supper

Radio 3 Listings for 3 – 9 May 2008 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 03 MAY 2008 SUNDAY 04 MAY 2008 to Supper. SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00b1npd) SUN 00:00 The Early Music Show (b007n30p) Interwoven with the poetry is music such as Schubert's Trout Including 1.00 Sibelius, Grieg, Mozart, Hindemith, Durufle. Emilio's Wedding Quintet, the chorus in Strauss' Die Fledermaus where the guests 3.25 Bach, Shostakovich, Rossini, Purcell, Wolf. 5.00 look forward to supper, and Biber's Mensa Sonora (music Kabalevsky, Purcell, Barber, Vivaldi, Biber, Sibelius, Chopin. Emilio's Wedding: Catherine Bott looks back on the life of suitable to accompany aristocratic dining) Emilio de Cavalieri, famous for co-ordinating the music for one of the most lavish wedding celebrations in history. There's the "Rice aria" from Rossini's Tancredi, which the food SAT 05:00 Through the Night (b00b1nq1) loving composer apparently composed whilst waiting for his Through the Night risotto to cook and Nellie Melba, the soprano who gave her SUN 01:00 Through the Night (b00b525r) name to the Peach Melba, sings the Melba Waltz. John Shea concludes the programme with music by Kabalevsky, Including 1.00 Berg, Strauss, Jernefelt, Debussy, Satie. 3.10 Purcell, Barber, Vivaldi, Biber, Sibelius, Chopin, Browne, Ravel, Clerambault, Brahms, Beethoven, Sibelius. 5.00 Rimsky- Plus popular food music by Fats Waller (Hold Tight I Want Faure and Kodaly. Korsakov, Schubert, Mozart, Bach, Haydn, Mendelssohn. Some Seafood Mama), The Beatles (Savoy Truffle) and Bob Dylan (Country Pie). SAT 07:00 Breakfast (b00b5d6f) SUN 05:00 Through the Night (b00b525t) Perhaps the most peculiar choice is a medieval song about eggs Including Vivaldi: Trio in C, RV82. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO) President

POSITION DESCRIPTION June 2021 Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO) President MSO seeks a business professional who will partner with veteran Music Director & Conductor Crafton Beck, to deliver exceptional orchestral music experiences and education programs that engage and include Mississippi communities throughout the state. Founded in 1944, the Mississippi Symphony Orchestra is the cornerstone of Mississippi performing arts and has a long history of innovation, creativity, and excellence. Led by Music Director Crafton Beck and based in the City of Jackson, MSO is an innovative regional orchestra that presents orchestral music performances, programs and education of the highest quality to residents and visitors of Mississippi. Known as the “Birthplace of America’s Music,” Mississippi has shaped the course of modern music with its contributions to blues, jazz, rock, country and gospel. BACKGROUND MSO has acted as a cultural trailblazer since its founding. As the largest professional performing arts organization in the state, the financially stable MSO performs approximately 20 concerts and approximately 100 full orchestra and small ensemble educational performances statewide for more than 30,000 Mississippians each year. The Selby and Richard McRae Foundation Bravo Series is MSO’s banner classical series of 5 concerts which are annually performed along with the 2 concert Pops Series at the 2,040 seat Thalia Mara Hall in downtown Jackson, while an equally successful Chamber Orchestra Series of four concerts is performed in intimate venues throughout Jackson and the region and the popular Pepsi Pops concert is performed at a local outdoor venue. MSO tours statewide as a full orchestra, chamber orchestra in three resident ensembles - Woodwind Quintet, Brass Quintet and String Quartet with annual and bi-annual visits to Vicksburg, Pascagoula, McComb, Brookhaven, Poplarville, and other cities. -

Thursday Playlist

February 20, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 in D Budapest Festival Orchestra/Fischer Philips 456 570 028945657028 Awake! Symphony in D, "The Petrification of Phineus and 00:13 Buy Now! Dittersdorf Cantilena/Shepherd Chandos 8564/5 5014682856423 his Friends" 00:31 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 076 in E flat Academy of Ancient Music/Hogwood BBC MM253 n/a Vonsattel/Sussmann/Swensen/O'Neill 01:01 Buy Now! Franck Piano Quintet in F minor Music@Menlo Live n/a 653738268220 /Finckel New York Chamber Music 01:35 Buy Now! Lully Suite ~ The Forced Marriage Dorian 90189 053479018922 Ensemble/Pederson 01:45 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Lars Vogt EMI 36080 094633608023 02:00 Buy Now! Weber Overture ~ Der Freischutz Philharmonia/Klemperer EMI 13073 n/a 02:11 Buy Now! Strauss, R. 2nd mvt (Andante) ~ Cello Sonata in F, Op. 6 Coppey/le Sage Harmonia Mundi 911550 794881314324 02:20 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 "Scottish" London Classical Players/Norrington EMI 54000 077775400021 Rimsky- 02:59 Buy Now! Ivan the Terrible National Philharmonic/Stokowski Sony Classical 62647 074646264720 Korsakov 03:04 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky The Seasons (orchestrated version) Moscow Chamber Orchestra/Orbelian Delos 3255 013491325521 03:48 Buy Now! Handel Concerto Grosso in G, Op. 6 No. 1 Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7895 078635789522 04:01 Buy Now! Devienne Flute Concerto No. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today. -

Unifying Elements of John Corigliano's

UNIFYING ELEMENTS OF JOHN CORIGLIANO'S ETUDE FANTASY By JANINA KUZMAS Undergraduate Diploma with honors, Sumgait College of Music, USSR, 1985 B. Mus., with the highest honors, Vilnius Conservatory, Lithuania, 1991 Performance Certificate, Lithuanian Academy of Music, 1993 M. Mus., Bowling Green State University, USA, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 2002 © Janina Kuzmas 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. ~':<c It CC L Department of III -! ' The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date J/difc-L DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT John Corigliano's Etude Fantasy (1976) is a significant and challenging addition to the late twentieth century piano repertoire. A large-scale work, it occupies a particularly important place in the composer's output of music for piano. The remarkable variety of genres, styles, forms, and techniques in Corigliano's oeuvre as a whole is also evident in his piano music.