Within the Shadow of the Cowboy: Myths and Realities of the Old American West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Recognizing Making Intimacy Vincent Tajiri Even Hotter!

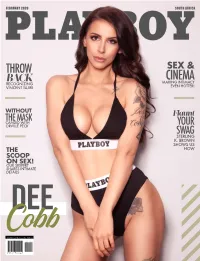

FEBRUARY 2020 SOUTH AFRICA THROW SEX & BACK CINEMA RECOGNIZING MAKING INTIMACY VINCENT TAJIRI EVEN HOTTER! WITHOUT Flaunt THE MASK CANDID WITH YOUR ORVILLE PECK SWAG STERLING K. BROWN SHOWS US THE HOW SCOOP ON SEX! OUR SEXPERT SHARES INTIMATE DETAILS Dee Cobb WWW.PLAYBOY.CO.ZA R45.00 20019 9 772517 959409 EVERY. ISSUE. EVER. The complete Playboy archive Instant access to every issue, article, story, and pictorial Playboy has ever published – only on iPlayboy.com. VISIT PLAYBOY.COM/ARCHIVE SOUTH AFRICA Editor-in-Chief Dirk Steenekamp Associate Editor Jason Fleetwood Graphic Designer Koketso Moganetsi Fashion Editor Lexie Robb Grooming Editor Greg Forbes Gaming Editor Andre Coetzer Tech Editor Peter Wolff Illustrations Toon53 Productions Motoring Editor John Page Senior Photo Editor Luba V Nel ADVERTISING SALES [email protected] for more information PHONE: +27 10 006 0051 MAIL: PO Box 71450, Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021 Ƶč%./0(++.ǫ(+'ć+1.35/""%!.'Čƫ*.++/0.!!0Ē+1.35/ǫ+1(!2. ČĂāĊā EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.playboy.co.za FACEBOOK: facebook.com/playboysouthafrica TWITTER: @PlayboyMagSA INSTAGRAM: playboymagsa PLAYBOY ENTERPRISES, INTERNATIONAL Hugh M. Hefner, FOUNDER U.S. PLAYBOY ǫ!* +$*Čƫ$%!"4!10%2!þ!. ƫ++,!.!"*!.Čƫ$%!"ƫ.!0%2!þ!. Michael Phillips, SVP, Digital Products James Rickman, Executive Editor PLAYBOY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING !!*0!(Čƫ$%!"ƫ+))!.%(þ!.Ē! +",!.0%+*/ Hazel Thomson, Senior Director, International Licensing PLAYBOY South Africa is published by DHS Media House in South Africa for South Africa. Material in this publication, including text and images, is protected by copyright. It may not be copied, reproduced, republished, posted, broadcast, or transmitted in any way without written consent of DHS Media House. -

Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory

DANGEROUSLY FREE: OUTLAWS AND NATION-MAKING IN LITERATURE OF THE INDIAN TERRITORY by Jenna Hunnef A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Jenna Hunnef 2016 Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory Jenna Hunnef Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2016 Abstract In this dissertation, I examine how literary representations of outlaws and outlawry have contributed to the shaping of national identity in the United States. I analyze a series of texts set in the former Indian Territory (now part of the state of Oklahoma) for traces of what I call “outlaw rhetorics,” that is, the political expression in literature of marginalized realities and competing visions of nationhood. Outlaw rhetorics elicit new ways to think the nation differently—to imagine the nation otherwise; as such, I demonstrate that outlaw narratives are as capable of challenging the nation’s claims to territorial or imaginative title as they are of asserting them. Borrowing from Abenaki scholar Lisa Brooks’s definition of “nation” as “the multifaceted, lived experience of families who gather in particular places,” this dissertation draws an analogous relationship between outlaws and domestic spaces wherein they are both considered simultaneously exempt from and constitutive of civic life. In the same way that the outlaw’s alternately celebrated and marginal status endows him or her with the power to support and eschew the stories a nation tells about itself, so the liminality and centrality of domestic life have proven effective as a means of consolidating and dissenting from the status quo of the nation-state. -

Aug/Sept 2018

COWBOY FAST DRAW ASSOCIATION S AUGUST/SEPTEMBER ’ 2018 UNSLIN ER S GOfficial Journal of the ’ Cowboy fast Draw assoCiation GAZETTE ~ Honoring the Romance and Legend of the Old West ~ Oklahoma State Virginia State Championship Championship page 8 page 10 Colorado State Great Northwest Championship Territorial page 19 Championship Four Corners page 12 Territorial Championship page 20 2018 Shoot for the Stars 4 Page Scholarship Fastest Gun Recipients Alive page 7 Insert in This Issue! PAGE 15 Cover Photo Courtesty Vic Torious Page 2 August/September 2018 Gunslinger’s Gazette The Choice of Champions HIGHLY REGARDED AS THE MOST DEPENDABLE SIX-GUN IN THE WORLD Gunslinger’s Gazette August/September 2018 Page 3 GUNSLINGER”S GAZETTE EDITORIAL Publisher ATTENTION Cowboy Fast Draw Association, LLC is like nothing around. What an amazing sport we Deadline to submit articles Director have! Please be sure to stop in the CFDA General Cal Eilrich “Quick Cal” #L2 store and say hello! for next Gazette is: Editor Holy Articles! This issue is jam packed Erika Frisk ,“Hannah Calder” #L46 with competition articles. Thank you so very much November 9th to all who sent in articles and pictures. I appreciate Please submit all articles and Contributing Editors you all so much! Many times there are so many pictures to: Alotta Lead #L37 great photos to choose from, but unfortunately not Mongo #L57 enough room to publish in the Gunslinger’s Ga- [email protected] zette. I have set up a 2018 Events album on our Copy Editor main CFDA facebook page. I will be adding pho- Erika Frisk, “Hannah Calder” t’s hard to believe, but summer has already come tos after each issue with the photos I published and Life #46 Ito an end. -

The American West; 1835-95 Key Topic 1: the Early Settlement of the West, C1835-95

The American West; 1835-95 Key Topic 1: The early settlement of the West, c1835-95 Background: The early settlement of the West is marked by tensions between the native Indians and the white man. The reasons why the settlers migrated West meant the new U.S government had to design a strategy to manage the native population. You need to study how the government tried to manage this migra- tion, how the natives reacted and how lawlessness was tackled in the new settlements which were created by those migrating West. American West Module 1: The early settlement of the West In this module you will revise; 1. The Plains Indians; their beliefs and way of life (The beliefs, structure and life of tribes U.S expansion West and the Permanent Indian Frontier, including the Indian Appropriations Act) 2. Migration and early settlement (Factors which encouraged migration West, the process and problems of migration (Case studies: Donner Party and Mormon migration, development and problems of white settle- ment farming) 3. Conflict and tension (Reasons for tensions be- tween settlers and Plains Indians - including the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1581, lawlessness in early towns and settlements and how this was tackled (by government and local communities) KT 1.1: The Plains Indians; their beliefs and way of life Society structure The Native Americans lived on the Great Plains A.K.A the Great American Desert an area of land in the centre of the USA which spans over 1,300,000 km/sq (over 5 times the area of great Britain!) Only the largest tribes were called ‘Nations’, and they consisted of tribes, sub tribes and bands. -

Highwayman Plan for Parents

Monday LO: I can deduce information about a character from a visual text. Have a look at the character in the picture. What can you actually see? What can you tell about him from the way he looks? Annotate your picture with descriptive language. Can you include any similes or metaphors? There are two examples on the picture already to get you started. Have a look at this website link to get to know more about Highwaymen. Are there any similarities to Robin Hood? http://www.localhistories.org/highwaymen.html Tuesday and Wednesday LO: I can identify key events in a narrative poem. Read the Highwayman by Alfred Noyes and watch the animation from the link below. Get to know the story. On your copy of the poem, look up any words you don’t know the meaning of in the interactive glossary and annotate it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLbfPsdlymg On the storyboard template, can you break the poem up into its different parts – writing notes and drawing pictures to go with each section. Here are the first three parts to get you started. Retell the story of the poem to a member of your family using your storyboard to support you. Thursday LO: I can recognise figurative language in a narrative poem. Read through the figurative language PowerPoint to learn more about metaphors and recap on similes and alliteration. Using the poem, complete the table of metaphors, similes and alliteration with examples. Then, have a go at magpieing words from the poem into the second page of the table. -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music's

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Musicology Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Saporito, Gabriella, "#Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8074. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8074 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #Canceled: Positionality and Authenticity in Country Music’s Cancel Culture Gabriella Saporito Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D., Chair Jennifer Walker, Ph.D. Matthew Heap, Ph.D. -

Revising the Western: Connecting Genre Rituals and American

CSCXXX10.1177/1532708614527561Cultural Studies <span class="symbol" cstyle="symbol">↔</span> Critical MethodologiesCastleberry 527561research-article2014 Article Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 2014, Vol. 14(3) 269 –278 Revising the Western: Connecting © 2014 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Genre Rituals and American Western DOI: 10.1177/1532708614527561 Revisionism in TV’s Sons of Anarchy csc.sagepub.com Garret L. Castleberry1 Abstract In this article, I analyze the TV show Sons of Anarchy (SOA) and how the cable drama revisits and revises the American Western film genre. I survey ideological contexts and tropes that span Western mythologies like landscape and mise-en- scene to struggles for family, community, and the continuation of Native American plight. I trace connections between the show’s fictitious town setting and how the narrative inverts traditional community archetypes to reinsert a new outlaw status quo. I inspect the role of border reversal, from open expansion in Westerns to the closed-door post-globalist world of SAMCRO. I quickdraw from a number of film theory scholars as I trick shoot their critiques of Western cinema against the updated target of SOA’s fictitious Charming, CA. I reckon that this revised update of outlaw culture, gunslinger violence, and the drama’s subsequent popularity communicates a post-9/11 trauma playing out on television. Through the sage wisdom of autoethnography, I recall personal memories as an ideological travelogue for navigating the rhetoric power this drama ignites. As with postwar movements of biker history that follow World War II and Vietnam, SOA races against Western form while staying distinctly faithful. -

Hell on Wheels

MercantileEXCITINGSee section our NovemberNovemberNovember 2001 2001 2001 CowboyCowboyCowboy ChronicleChronicleChronicle(starting on PagepagePagePage 90) 111 The Cowboy Chronicle~ The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Shooting Society ® Vol. 21 No. 11 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. November 2008 . HELL ON WHEELS . THE SASS HIGH PLAINS REGIONAL By Captain George Baylor, SASS Life #24287 heyenne, Wyoming – The HIGHLIGHTS on pages 70-73 very name conjures up images of the Old West. chief surveyor for the Union Pacific C Wyoming is a very big state Railroad, surveyed a town site at with very few people in it. It has what would become Cheyenne, only 500,000 people in the entire Wyoming. He called it Cow Creek state, but about twice as many ante- Crossing. His friends, however, lope. A lady at Fort Laramie told me thought it would sound better as Cheyenne was nice “if you like big Cheyenne. Within days, speculators cities.” Cheyenne has 55,000 people. had bought lots for a $150 and sold A considerable amount of history them for $1500, and Hell on Wheels happened in Wyoming. For example, came over from Julesburg, Colorado— Fort Laramie was the resupply point the previous Hell on Wheels town. for travelers going west, settlers, and Soon, Cheyenne had a government, the army fighting the Indian wars. but not much law. A vigilance com- On the far west side of the state, mittee was formed and banishments, Buffalo Bill built his dream town in even lynchings, tamed the lawless- Cody, Wyoming. ness of the town to some extent. Cheyenne, in a way, really got its The railroad was always the cen- start when the South seceded from tral point of Cheyenne. -

06 21 2016 (Pdf)

6-21-16 sect. 1.qxp:Layout 1 6/16/16 11:56 AM Page 1 Grandin emphasizes stockmanship at 5th International Symposium on Beef Cattle Welfare By Donna Sullivan, Editor and they all had the lower worse.” The one message that Dr. hair whorls. Cattle overall Grandin emphasized that Temple Grandin has champi- are getting calmer.” an animal’s first experience oned throughout her career is But she cautioned against with a new person, place or that stockmanship matters. over-emphasizing tempera- piece of equipment needs to And the world-renowned ment. “We don’t want to turn be a good one. “New things Colorado State University beef cattle into a bunch of are scary when you shove professor and livestock han- Holsteins,” she warned. them in their face,” she said. dling expert didn’t vary from “That would probably be a “But they are attractive when that theme as she presented really bad idea because we they voluntarily approach. A at the 5th International Sym- want a cow that’s going to basic principle is that when posium on Beef Cattle Wel- defend her calf.” you force animals to do fare hosted by Kansas State She also pointed out that something, you’re going to University’s Beef Cattle In- temperament scores can be get a lot more fear stress than stitute in early June. She pre- changed with experience, by when they voluntarily go sented a great deal of re- acclimating cattle to new through the facility.” search illustrating the corre- people and experiences. Un- Grandin said she has seen lation between how cattle are fortunately, people don’t al- an improvement in people’s handled and their overall ways want to take the time attitudes towards animals performance. -

The Bandit in History and Culture in Latin America

1 Introduction: The idea of a ‘Golden Age’ of Latin American banditry, 1850-1950 This book examines the cultural history of banditry in Latin America from 1850 to 1950. It takes these dates because this is the period during which the so-called social bandit, a prototype first suggested By Eric Hobsbawm (1969), proliferated on the continent, certainly in myth if not in actual recorded history. This was an era of dramatic political and social change in Latin America, when nineteenth-century wars of independence severed these colonies from their Spanish and Portuguese rulers and when the Mexican Revolution (1910- 1920), at the start of the twentieth century, overturned the status quo once again. During this period bandits proved to be ideal cultural vehicles through which to channel nationalism and the desire for social justice, whilst, paradoxically they were also cast, according to the political currents of the time, by politicians, writers, artists and filmmakers as dangerous enemies of these fragile new nation states who struck at the fabric of society and threatened to plunge these new countries back to a pre-independence state of anarchy and barbarism. However, whether friend or foe to the nation, bandits and their accompanying folklore ensured that they were at the heart of popular culture in the period 1850-1950, making this very much a Golden Age of Latin American banditry. Latin America here is understood not geographically but more broadly to refer to those areas where Iberian colonial cultures took root and where the contemporary postcolonial situation sees a majority of Spanish-speakers still living, that is the Hispanic USA.1 The book focuses on a range of bandit life stories from the region, from a historical perspective, as well as a wide range of cultural representations of which the most significant are literary works in which the bandit plays a central role, with Los de abajo, The Underdogs (1915) the classic Mexican Revolution novel by Mariano Azuela forming the nucleus of the study. -

Robin Hood the Brute: Representations of The

Law, Crime and History (2016) 2 ROBIN HOOD THE BRUTE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE OUTLAW IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CRIMINAL BIOGRAPHY Stephen Basdeo1 Abstract Eighteenth century criminal biography is a topic that has been explored at length by both crime historians such as Andrea McKenzie and Richard Ward, as well as literary scholars such as Lincoln B. Faller and Hal Gladfelder. Much of these researchers’ work, however, has focused upon the representation of seventeenth and eighteenth century criminals within these narratives. In contrast, this article explores how England’s most famous medieval criminal, Robin Hood, is represented. By giving a commentary upon eighteenth century Robin Hood narratives, this article shows how, at a time of public anxiety surrounding crime, people were less willing to believe in the myth of a good outlaw. Keywords: eighteenth century, criminal biography, Robin Hood, outlaws, Alexander Smith, Charles Johnson, medievalism Introduction Until the 1980s Robin Hood scholarship tended to focus upon the five extant medieval texts such as Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, and A Gest of Robyn Hode (c.1450), as well as attempts to identify a historical outlaw.2 It was only with the work of Stephen Knight that scholarship moved away from trying to identify a real outlaw as things took a ‘literary turn’. With Knight’s work also the post- medieval Robin Hood tradition became a significant area of scholarly enquiry. His recent texts have mapped the various influences at work upon successive interpretations of the legend and how it slowly became gentrified and ‘safe’ as successive authors gradually ‘robbed’ Robin of any subversive traits.3 Whilst Knight’s research on Robin Hood is comprehensive, one genre of literature that he has not as yet examined in detail is eighteenth century criminal biography.