4XJG R 7'1985 Sheila L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twyla Tharp Th Anniversary Tour

Friday, October 16, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 17, 2015, 8pm Sunday, October 18, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour r o d a n a f A n e v u R Daniel Baker, Ramona Kelley, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp in Preludes and Fugues Choreography by Twyla Tharp Costumes and Scenics by Santo Loquasto Lighting by James F. Ingalls The Company John Selya Rika Okamoto Matthew Dibble Ron Todorowski Daniel Baker Amy Ruggiero Ramona Kelley Nicholas Coppula Eva Trapp Savannah Lowery Reed Tankersley Kaitlyn Gilliland Eric Otto These performances are made possible, in part, by an Anonymous Patron Sponsor and by Patron Sponsors Lynn Feintech and Anthony Bernhardt, Rockridge Market Hall, and Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.”—Twyla Tharp, 2015 PROGRAM First Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers The Practical Trumpet Society Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall by John Zorn. Used by arrangement with Hips Road. PAUSE Preludes and Fugues Dedicated to Richard Burke (Bay Area première) Choreography Twyla Tharp Music Johann Sebastian Bach Musical Performers David Korevaar and Angela Hewitt Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company The Well-Tempered Clavier : Volume 1 recorded by MSR Records; Volume 2 recorded by Hyperi on Records Ltd. INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Second Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers American Brass Quintet Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. -

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

IN the WINGS 8 P.M

IN THE WINGS 8 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 28 8 p.m. Friday, March 1 2 & 8 p.m. Saturday, March 2 DANCE Choreographers’ Showcase SERIES PRESENTS Deirdre Carberry, director Experience the next wave of emerging choreographers as CCM dance majors take the stage with exciting and diverse new works. These choreographers have cast CCM dance majors to tell their stories through classical, modern and contemporary genres. Location: Patricia Corbett Theater Admission: FREE _____ CCM BALLET ENSEMBLE 8 p.m. Thursday, April 18 8 p.m. Friday, April 19 PRESENTS: 2 & 8 p.m. Saturday, April 20 Spring Dance Concert With Chamber Choir and Chamber Players Jiang Qi, director CCM faculty present new works this spring! Deirdre Carberry choreographs “Kitri’s Wedding” from the full-length ballet Don FALL DANCE Quixote (Act III), which was originally choreographed by Petipa in 1869 and will include the infamous bravura wedding Grand Pas de Deux. Created with a National Endowment for the Arts Choreography CONCERT Fellowship, Michael Tevlin’s “…And Ye Shall Be as Gods…” depicts the story of Adam and Eve, danced to Igor Stravinsky’s Serenade in A for piano with original scenic design by C.D. Higgins. In addition, Judith MICHAEL TEVLIN, director Mikita will choreograph a modern piece, featuring the CCM Chamber Choir. Finally, the Chamber Players will accompany Jiang Qi’s exciting new work. Location: Patricia Corbett Theater Tickets: $15 general admission, $10 non-UC students, UC students FREE. Friday, November 30, 2012, 8:00 p.m. Saturday, December 1, 2:00 and 8:00 p.m. Sunday, December 2, 2:00 p.m. -

Tasha Golis Acrobatics, Barre Fitness, Hip Hop, MSEE Lead Faculty, Jr

Tasha Golis Lisa Scott Acrobatics, Barre Fitness, Hip Hop, MSEE Lead Faculty, Fitness Director & Barre Fitness Jr. & Apprentice Company Assistant Choreographer Lisa has always been fitness oriented. Lisa was formerly of the Barre 54 team, the first studio to bring Tasha is an Orlando native who grew up dancing. After graduating from the University of Florida, Barre workouts to the Orlando area. Parlaying her dance training as a child, into a strong she returned to Central Florida to perform at WDW, Universal, and Sea World. She was invited to professional career as an actress, dancer, and stunt performer, she has enjoyed performing on join an international cast onboard Costa Cruise Lines and began an exciting career performing stages throughout the United States, Europe, and as far east as Tokyo, Japan. As a professional around the globe. She was dance captain for numerous cruising companies and saw the world. model and spokesperson, Lisa has endorsed many quality fitness products and realizes the Performance contracts followed in Australia, Guam, and South America. Tasha is back in Florida importance of not only physical fitness, but mental discipline and commitment. As a break from and loving it! You can find her teaching at the barre, performing on stage, or boating and water her demanding schedule, Lisa finds comfort in reading a good book or watching an old classic skiing. movie. Her favorite role is playing mom to her 13 yr. old daughter, Emma. Douglas Horne Ballet & Brain Fitness Robert Scott Douglas Horne danced professionally after studying on full scholarship with American Ballet Theatre (New The Art & Technique of Acting York), Miami City Ballet (Miami, Florida) and Studio Maestro (New York). -

Grew up in New Jersey and Studied Ballet at a Young Age with the New Jersey Ballet School

Patricia Brown: grew up in New Jersey and studied ballet at a young age with the New Jersey Ballet School. As a teenager, Patricia was awarded full scholarships to the American Ballet Theatre School and the Joffrey Ballet School. Ms. Brown has danced professionally with the New Jersey Ballet Company, Joffrey II Ballet Company, Cleveland Ballet (soloist), the Elliot Feld Ballet, and the Joffrey Ballet Company (soloist). She has worked with many well-known choreographers such as Agnes DeMille, Anthony Tudor, Gerald Arpino, Elliot Feld, Paul Taylor, Laura Dean, and Dennis Nahat. Ms. Brown has served as principal teacher for trainee programs at the Milwaukee Ballet School, Joffrey Ballet School, Harrisburg Ballet School, Nashville Ballet School, The Dance Center, and the Mill Ballet School. She has taught company classes for Joffrey II Ballet, the Elliot Feld Ballet, Nashville Ballet, Harrisburg Ballet, Brandywine Ballet Theatre, the Roxey Ballet, and she has served as Ballet Mistress for the Pennsylvania Ballet. Ms. Brown has choreographed ballets performed at Joffrey Ballet workshop, Milwaukee Ballet workshop, Harrisburg Ballet Company, Brandywine Ballet Theater, the Roxey Ballet and for the international competition at Avery Fisher Hall in New York. Patricia has been asked to join the faculty of the Joffrey School in New York City and commutes weekly to teach class. Val Gontcharov: In 1974 at the age of 11 Val successfully competed against 40 other applicants for the one opening in the Kieu Ballet School. After graduation in 1982, five different companies offered him positions, but he chose the Donetsk Ballet to be closer to his parents' home. -

2019-2020 Course Catalog + Program Policies

2019-2020 Course Catalog + Program Policies Phone: 541-342-4611 Email: [email protected] Web: www.balletfantastique.org Academy of Ballet Fantastique Professional Division Program Guide ACADEMY OF BALLET FANTASTIQUE 1... PROFESSIONAL DIVISION COURSE CATALOG & PROGRAM INFORMATION 2019-20 Academy of Ballet Fantastique Professional Division Program Guide FOR MORE INFORMATION CITY CENTER FOR DANCE ANNEX STUDIO 541.342.4611 960 Oak St. 60 E. 10th Ave [email protected] Eugene, OR 97401 Eugene, OR 97401 www.balletfantastique.org (Oak b/t Broadway & 10th) (10th & Oak Alley) Northeast elevator Southwest elevator ACADEMY OF BALLET FANTASTIQUE 2... PROFESSIONAL DIVISION COURSE CATALOG & PROGRAM INFORMATION 2019-20 Academy of Ballet Fantastique Professional Division Program Guide CORE PROGRAM Official training school of the Ballet Fantastiq ue Company, a Resident Company of the Hult Center for the Performing Arts Academy of Ballet Fantastique students benefit from the association with a professional company, daily mentorship by top professional company dancers and teachers hailing from all over the world. The benefits of this association include work under and alongside top professionals in the industry, exposure to and immersion in a professional standards and atmosphere, and experience watching and participating in professional productions with live musicians. Training Syllabus Our Professional Division follows the eight levels of the internationally renowned Vaganova Syllabus, a notated, progressive -

Press Release the Dance Complex Presents Winter Wonder Dance Festival 2019

PRESS RELEASE 536 Massachusetts Ave. - Cambridge MA 02139 - dancecomplex.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Kledia Spiro Communications Director [email protected] 617-547-9363 THE DANCE COMPLEX PRESENTS WINTER WONDER DANCE FESTIVAL 2019 Photo: courtesy of 10 Hairy Legs, featured in this year’s Winter Wonder Cambridge, MA- December 6th 2019: The Dance Complex’s annual Winter Wonder Dance Festival features classes, repertory, and performance opportunities with internationally renowned Teaching Artists, both Boston-based and from around the world. Held every December, this festival is an opportunity to kick off the New Year with time dedicated to taking your next deep step in dance and movement. This year’s festival will be held Friday, December 27 to Tuesday, December 31, and will feature world dance classes: Afro Haitian, Senior Flamenco, All Levels Flamenco, Gaga/People, and Gaga/Dancers. Dancers can gain new experiences through Improv Jam and partnering classes as well. We are offering classes for all levels, plus for those who have never danced before and those who may be returning, so everyone can find something they love! - continued- Teaching artists are BOTH Boston based, The Dance Complex regulars, and are ALSO from Broadway and Tel Aviv. The final day of the festival will be a day of movement and reflection, focused on the mind-body connection. Reign in the New Year with a yoga class and become more in tune with your body for a new you in movement, while you sip hot chocolate. Each year during Winter Wonder Dance Festival, we highlight our teaching artists through performance! Two informal performances will be held in our great Studio 7 where the bar is always open and mingling between pop-up performances is encouraged. -

Ballet West Student In-Theater Presentations

Ballet West for Children Presents Ballet and The Sleeping Beauty Dancers: Soloist Katie Critchlow, First Soloist Sayaka Ohtaki, Principal Artist Emily Adams, First Soloist Katlyn Addison, Demi-Soloist Lindsay Bond Photo by Beau Pearson Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Adapted from Original Choreography: Marius Petipa Photo: Quinn Farley Costumes: David Heuvel Dear Dance enthusiast, Ballet West is pleased that you are viewing a Ballet West for Children Presentation as a virtual learning experience. Enclosed you will find the following information concerning this performance: 1. Letter from Artistic Director, Adam Sklute. 2. Letter to the parent/guardian of the students who will be viewing. 3. Specific Information on this Performance, including information on the ballet, music, choreography, follow-up projects and other pertinent material has also been compiled for the teacher's information. 4. We report to the Utah State Board of Education each year on our educational programs, and need your help. Usually, we gather information from teachers as to how the student reacted and what they may have learned from their experience. We’d love to hear from you by filling out our short Survey Monkey listed on our virtual learning page. We don’t have a way to track who and how many people are taking advantage of this opportunity and this will help us to know how we’re doing. You can always email me directly. Thank you very much for your interest in the educational programs of Ballet West. Please call if I may provide any additional information or assistance to you and your school. I can be reached at 801-869-6911 or by email at [email protected]. -

Showcase-2021-Playbill.Pdf

Presents Summer Celebration! Featuring The Fairy Doll Directed by Stephanie Heston & Alexander Smirnov Funded in part through the Kansas Creative Arts Industries Commission, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts -Act 1- Florence Music: Pytor Tchaikovsky Choreography: Marcus Oatis Costumes: provided by Kansas City Ballet Featuring: Summer Intensive Group A Choreography Class Demonstration Choreography by and Featuring: Summer Intensive Group B Jazz Class Demonstration Choreography: Erinn Bird Featuring: Summer Intensive Groups C & D Pilates Class Demonstration Choreography: Amy Reazin Featuring: Beginning Summer Intensive Dancers Young Dancer Demonstrations Choreography: Erinn Bird ‘Small World’ Featuring: Fairy Doll Ballet Camps (ages 3-4) ‘Music Box’ Featuring: Fairy Doll Ballet Camps (ages 5-6) Repertory Class Demonstration ‘Paquita’ World Premiere April 1, 1846 Paris Opera Ballet Music: Edouard Deldevez & Ludwig Minkus Original Choreography: Joseph Mazilier Re-staged by Stephanie Heston and Alexander Smirnov Featuring: Summer Intensive Groups A, B, C, D -Intermission- -Act 2- The Fairy Doll Music: Josef Bayer Staged by: Stephanie Heston and Alexander Smirnov Light Design: Erica Maholmes SCENE ONE A bustling toy shop enjoys brisk trade during the daytime. Shop Keepers Claire Edmonds and Aiyanna Graham Shop Owner Alexander Smirnov First Family Erinn Bird and Jason Schone with Crosby Beyer, Scarlett Gann, Elizaveta Smirnov, JT Terry Second Family Josie Werts and Rory Pischer with Burhan Khmous, Isabelle Robinson French -

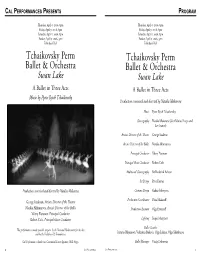

Perm Ballet Notes.Indd

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Th ursday, April , , pm Th ursday, April , , pm Friday, April , , pm Friday, April , , pm Saturday, April , , pm Saturday, April , , pm Sunday, April , , pm Sunday, April , , pm Zellerbach Hall Zellerbach Hall Tchaikovsky Perm Tchaikovsky Perm Ballet & Orchestra Ballet & Orchestra Swan Lake Swan Lake A Ballet in Th ree Acts A Ballet in Th ree Acts Music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Production conceived and directed by Natalia Makarova Music Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Choreography Natalia Makarova (after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov) Artistic Director of the Th eatre George Isaakyan Artistic Director of the Ballet Natalia Akhmarova Principal Conductor Valery Platonov Principal Guest Conductor Robert Cole Additional Choreography Sir Frederick Ashton Set Design Peter Farmer Production conceived and directed by Natalia Makarova Costume Design Galina Solovyeva George Isaakyan, Artistic Director of the Th eatre Production Coordinator Dina Makaroff Natalia Akhmarova, Artistic Director of the Ballet Production Assistant Olga Evreinoff Valery Platonov, Principal Conductor Robert Cole, Principal Guest Conductor Lighting Sergei Martynov Ballet Coaches Th is performance is made possible, in part, by the National Endowment for the Arts and by the Vodafone-US Foundation. Rimma Shlyamova, Valentina Baikova, Olga Lukina, Olga Salimbaeva Cal Performances thanks our Centennial Season Sponsor, Wells Fargo. Ballet Manager Vitaly Dubrovin 4 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 5 CAST SYNOPSIS Odette/Odile Elena Kulagina (April ) frightened, Odette tells the Prince the story of her Natalia Moiseeva (April , , ) plight. Th e spell that keeps them swans by day and maidens at night can only be broken if a man who Prince Siegfried Sergei Mershin (April , , ) has never loved before swears eternal fi delity to Alexey Tyukov (April ) her. -

International Exchange in Dance Annual of Contemporary Dance Double Issue 3.50 1963 • 1964

7 INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE IN DANCE ANNUAL OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE DOUBLE ISSUE 3.50 1963 • 1964 • • WW * Copyright 1963 by Impulse Publications, Inc. l^yyKA' \s<s y Inde x S. I. Hayakawa THE UNACKNOWLEDGED LEGISLATORS 5 Rhoda Kellogg THE BIOLOGY OF ESTHETICS 9 Adele Wenig "IMPORTS AND EXPORTS" —1700-1940 16 Walter Sorell SOL THE MAGNIFICENT 29 Arthur Todd DANCE AS UNITED STATES CULTURAL AMBASSADOR 33 Walter Sorell A FAREWELL AND WELCOME 44 RECENT "EXPORTS" 46 as told to Rhoda Slanger Jean Erdman Meg Gordeau Paul Taylor as told to Joanna Gewertz Merce Cunningham Ann Halprin Jerry Mander THE UNKNOWN GUEST 56 Isadora Bennett SECOND THOUGHTS 63 Letter from Thomas R. Skelton STAGING ETHNIC DANCE 64 Thomas R. Skelton BALLET FOLKLORICO 71 Antonio Truyol NOTES FROM THE ARGENTINE 73 Ester Timbancaya DANCE IN THE PHILIPPINES^ 76 Joanna Gewertz THE BACCHAE 80 Ann Hutchinson NOTATION — A Means of International Communication 82 in Movement and Dance QLA Margaret Erlanger DANCE JOURNEYS 84 SPONSORSHIP AND SUPPORT 88 t> Editor: Marian Van Tuyl Editorial Board: Doris Dennison, Eleanor Lauer, Dorothy Harroun, Ann Glashagel, Joanna Gewertz; Elizabeth Harris Greenbie, Rhoda Kellogg, David Lauer, Bernice Peterson, Judy Foster, Adele Wenig, Rhoda Slanger, Ann Halprin, Dorrill Shadwell, Rebecca Fuller. Production Supervision: Lilly Weil Jaffe ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Cover design by David Lauer Photographs by courtesy of: San Francisco Chronicle 15 Harvard Theatre Collection 18, 19, 22, 23 Dance Collection: New York Public Library 21, 25, 26 Hurok Attractions, New York 29, 30, 31 Studio Roger Bedard, Quebec 31 Fay Foto Service, Inc., Boston 32 U.S. Information Service, Press Section, Photo Laboratory, Saigon, Vietnam 33 U.S. -

Make the Most of Your Dance Experience

Make the most of your New York City Dance Experience 2020 PREVIEW PERFORMANCE TOURS WORKSHOPS & MASTER CLASSES SPECIAL EVENT PLANNING & PRODUCTION PERFORMANCE EXCHANGE PROGRAM ONCE IN A LIFETIME EXPERIENCES • CUSTOMIZED WORKSHOPS & MASTER CLASSES • OPEN & PRIVATE CLASSES • PERFORMANCE EXCHANGE PROGRAM • PERFORMANCE OPPORTUNITIES • LEGACY 2020 EVENT TOUR UNIQUE & EXCITING OPPORTUNITIES • 9/11 Memorial & Museum • The Freedom Tower’s One World Observatory • Empire State Building Observatory • Broadway Show • Intrepid Air, Sea & Space Museum • Museum of Natural History • Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island Cruise • New York City Ballet Performance • United Nations • Radio City Music Hall Backstage Tour • Rockefeller Center • Top of the Rock • St. Patrick’s Cathedral • Lincoln Center • ABC’s Good Morning America • NBC Studio Tour THE POSSIBILITIES ARE ENDLESS! NEW YORK NEW YORK A CITY SO GREAT THEY NAMED IT TWICE! If New York is your destination, we are here for you LITERALLY it’s our home! Located just minutes from the heart of New York City, Educational Performance Tours is proud to offer a wide range of programs enabling your students to take full advantage of this great city! Our unique philosophy, “it’s not just about competition, but also opportunity” sets us apart from the standard “dance competition and convention” experience and has allowed us to inspire and educate young dancers. Our customized workshops and master classes offer dance groups the rare opportunity to interact and dance with prominent members of the NYC performing arts