Click the Image Above to View the History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Parking Map.Pdf

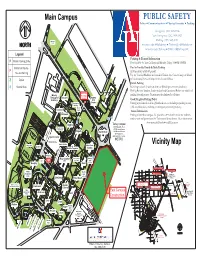

Main Campus TenleyPUBLIC Campus SAFETY Police ʀ Communications ʀ Physical Security ʀ Parking Future Home of Washington College of Law Emergency: (202) 885-3636 Non-Emergency: (202) 885-2527 Mass Ave Parking: (202) 885-3111 Tenley Field American.edu/PublicSafety ʀ Twitter @AUPublicSafetyCircle American.edu/Parking ʀ Twitter @ParkingatAU Legend Parking & Transit Information P Permit Parking Only Permit or Pay-As-You-Go RequiredUNDER: Monday-Friday, 8:00AM-5:00PM CONSTRUCTION Permit or PayͲAsͲ Pay-As-You-Go Hourly & Daily Parking P $2.00 per hour or $16.00Dunblane per day YouͲGo Parking Pay-As-You-Go Machines are located in Katzen Arts Center Garage or School of International Service Garage in the elevator lobbies. Z ZipCar Massachusetts Avenue Permit Parking S ShuƩle Stop $126.00 per month (Faculty & Staff) or $506.00 per semester (Students) Parking Permits (Student, Faculty & Staff and Occasional Parker) are valid in all Admissions Nebraska Wesley parking lots and garages. Permits must be displayed at all times. Welcome Theological Cassell Center Katzen Seminary Arts Good Neighbor Parking Policy Center President's P Parking is prohibited on all neighborhood streets, including at parking meters, Building Glover while attending class, working, or visiting any university property. Leonard Gate Transit Information University Avenue McDowell Parking is limited on campus. AU provides a free shuttle service for students, McDowell S S faculty, staff and guests from the Tenleytown Metro Station. More information: S American.edu/Shuttle ʀ goDCgo.com -

Government of the District of Columbia Advisory Neighborhood Commission 3B Glover Park and Cathedral Heights

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ADVISORY NEIGHBORHOOD COMMISSION 3B GLOVER PARK AND CATHEDRAL HEIGHTS ANC – 3B Minutes November 13, 2008 A quorum was established and the meeting was called to order at 7:05 p.m. The Chair asked if there were any changes to the agenda. Under New Business, liquor license renewal requests for Whole Foods and Glover Park Market were tabled as well as the administrative item on “Consideration of Proposed Changes to the ANC Grant Guidelines.” The agenda was modified, moved, properly seconded, and passed by unanimous consent. All Commissioners were present: 3B01 – Cathy Fiorillo 3B02 – Alan Blevins 3B01 – Melissa Lane 3B04 – Howie Kreitzman, absent 3B05 – Brian Cohen 2nd District Police Report Crime and Traffic Reports. Crime is slightly up over last year with the police blaming the economy. During October there were 42 thefts from autos, half of them were GPS’s. As always, police recommended that citizens lock their cars and do not leave anything out in plain view. Citizens should do the same with their homes and garages. There have been a number of thefts from garages when the home owner left their garage door open. Officer Bobby Finnel is being transferred into PSA 204 from the PSA that encompasses Friendship Heights. Officer Dave Baker gave the traffic report. Every month, Officer Baker plans to give a tip for citizens. This month he talked about license tags for non-traditional motor vehicles. Officer Baker distributed a tip sheet on this subject. Any motorcycle that has wheels less than 16” in diameter and a motorized bicycle that has wheels greater than 16” are required to register. -

Individual Projects

PROJECTS COMPLETED BY PROLOGUE DC HISTORIANS Mara Cherkasky This Place Has A Voice, Canal Park public art project, consulting historian, http://www.thisplacehasavoice.info The Hotel Harrington: A Witness to Washington DC's History Since 1914 (brochure, 2014) An East-of-the-River View: Anacostia Heritage Trail (Cultural Tourism DC, 2014) Remembering Georgetown's Streetcar Era: The O and P Streets Rehabilitation Project (exhibit panels and booklet documenting the District Department of Transportation's award-winning streetcar and pavement-preservation project, 2013) The Public Service Commission of the District of Columbia: The First 100 Years (exhibit panels and PowerPoint presentations, 2013) Historic Park View: A Walking Tour (booklet, Park View United Neighborhood Coalition, 2012) DC Neighborhood Heritage Trail booklets: Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail (2006); Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail (2008); A Self-Reliant People: Greater Deanwood Heritage Trail (2009); Cultural Convergence: Columbia Heights Heritage Trail (2009); Top of the Town: Tenleytown Heritage Trail (2010); Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail (2011); Lift Every Voice: Georgia Avenue/Pleasant Plains Heritage Trail (2011); Hub, Home, Heart: H Street NE Heritage Trail (2012); and Make No Little Plans: Federal Triangle Heritage Trail (2012) “Mount Pleasant,” in Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (Kathryn Schneider Smith, editor, Johns Hopkins Press, 2010) Mount -

Campus Maps, American University

American University Maps Home| Main Campus | Tenley | 4200 Office | New Mexico | Brandywine click here for html version of map DIRECTIONS American University is located on Ward Circle, at the intersection of Massachusetts and Nebraska Avenues, NW, in Washington, DC. BY CAR From northeast of Washington (New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore), follow Interstate 95 south to Interstate 495 west toward Silver Spring. See from Interstate 495 (Capital Beltway). From south or west of Washington (Norfolk, Richmond, Charlottsville) follow interstate 95 north or Interstate 66 east to Interstate 495, the Capital Beltway. Follow Interstate 495 north. See from Interstate 495 (Capital Beltway). From northwest of Washington (western Pennsylvania, western Maryland), follow Interstate 270 south. Where Interstate 270 divides, follow the right-hand branch toward norther Virginia (not towards Washington). Merge with Interstate 495, the Capital Beltway, and soon afterwards take exit 39, River Road. See from Interstate 495 (Capital Beltway). From Interstate 495 (Capital Beltway), take exit 39 and carefully follow the signs for River Road (Maryland Route 190) east toward Washington. Continue east on River Road to the fifth traffic light. Turn right onto Goldsboro Road (Maryland Route BY METRO BUS OR RAIL 614). At the first traffic light, turn left onto Massachusetts Metro Map Avenue (Maryland Route 396). Continue on Massachusetts Avenue for about two miles, through the first traffic circle (Westmoreland Circle). About on mile further on, enter a second From Union Station, National Airport or downto traffic circle (Ward Circle). Take the first right turn out of the Washington: Washington's Metrorail opens 5:30 a.m. weekdays circle, onto Nebraska Avenue. -

Tenleytown Encompasses the Business District Along Wisconsin Avenue from (About) Upton Street to Fessenden Street, and the Surrounding Residential Neighborhoods

Tenleytown encompasses the business district along Wisconsin Avenue from (about) Upton Street to Fessenden Street, and the surrounding residential neighborhoods. A writer in Salon magazine, describing his visit to one of the neighborhood's more unusual businesses , characterized Tenleytown as "a trendy shop-and-cafe zone a few miles north of downtown Washington;" it's a fair description. Indeed, Tenleytown has one of the more eclectic mixes of shops and cafes in town. You need not leave the neighborhood to buy rare cigars, obscure golf supplies, and rugged outdoor gear. You can get a winter tan, learn a foreign language, or -- maybe -- have an out-of-body experience (see link in previous paragraph). If you fall ill, Tenleytown has holistic healers and acclaimed chicken soup with matzoh balls. If all you need to feel better is caffeine and conversation, the neighborhood sports at least three cafes. HISTORY Tenleytown has been around for a while. Eighteenth-Century locals called the place "Tennalytown," after the roadside tavern run by a John Tennally. During the civil war, the neighborhood -- then known as Tenleytown -- hosted a strategically important military installation, Fort Reno . Built on Washington's highest point (429 feet), Fort Reno was the largest and strongest of a string of forts encircling the city . In July of 1864, the fort saw action when General Jubal A. Early led 22,000 Confederates against the 9,000 Union troops guarding Washington. For the most part, the battle unfolded just across the District line in Bethesda and Chevy Chase, but some close-quarters fighting seems to have occurred in Tenleytown and the surrounding area. -

Historic District Vision Faces Debate in Burleith

THE GEORGETOWN CURRENT Wednesday, June 22, 2016 Serving Burleith, Foxhall, Georgetown, Georgetown Reservoir & Glover Park Vol. XXV, No. 47 D.C. activists HERE’S LOOKING AT YOU, KID Historic district vision sound off on faces debate in Burleith constitution ciation with assistance from Kim ■ Preservation: Residents Williams of the D.C. Historic By CUNEYT DIL Preservation Office. The goal of Current Correspondent divided at recent meeting the presentation, citizens associa- By MARK LIEBERMAN tion members said, was to gather Hundreds of Washingtonians Current Staff Writer community sentiments and turned out for two constitutional address questions about the impli- convention events over the week- Burleith took a tentative step cations of an application. Many at end to give their say on how the toward historic district designa- the meeting appeared open to the District should function as a state, tion at a community meeting benefits of historic designation, completing the final round of pub- Thursday — but not everyone was while some grumbled that the pre- lic comment in the re-energized immediately won over by the sentation focused too narrowly on push for statehood. prospect. positive ramifications and not The conventions, intended to More than 40 residents of the enough on potential negative ones. hear out practical tweaks to a draft residential neighborhood, which Neighborhood feedback is cru- constitution released last month, lies north and west of George- cial to the process of becoming a brought passionate speeches, and town, turned out for a presentation historic district, Williams said dur- even songs, for the cause. The from the Burleith Citizens Asso- See Burleith/Page 2 events at Wilson High School in Tenleytown featured guest speak- ers and politicians calling on the city to seize recent momentum for Shelter site neighbors seek statehood. -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Transportation Impact Study American University – Tenley Campus Washington, DC

Preliminary Transportation Impact Study American University – Tenley Campus Washington, DC August 29, 2011 Prepared by: 1140 Connecticut Avenue 3914 Centreville Road 7001 Heritage Village Plaza Suite 600 Suite 330 Suite 220 Washington, DC20036 Chantilly, VA20151 Gainesville, VA20155 Tel: 202.296.8625 Tel: 703.787.9595 Tel: 703.787.9595 Fax: 202.785.1276 Fax: 703.787.9905 Fax: 703.787.9905 www.goroveslade.com This document, together with the concepts and designs presented herein, as an instrument of services, is intended for the specific purpose and client for which it was prepared. Reuse of and improper reliance on this document without written authorization by Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc., shall be without liability to Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc. Preliminary Transportation Impact Study – Tenley Campus Gorove/Slade Associates TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction & Site Review ..................................................................................................................................................... -

District of Columbia Tour Bus Management Initiative Final Report

US Department of Transportation Research and Special Programs Administration District of Columbia Tour Bus Management Initiative Final Report Prepared for District of Columbia Department of Transportation National Capital Planning Commission Washington Convention and Tourism Corporation Downtown DC Business Improvement District Office of DC Councilmember Sharon Ambrose Prepared by Volpe National Transportation Systems Center October 2003 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction . 1 2.0 Best Practices Review . 3 3.0 Solutions Matrix and Site Analysis . 30 4.0 Summary and Conclusions . 71 Appendix A: Stakeholder Interviews . 77 Appendix B: Tour Bus Counting Plan . 95 Appendix C: Preliminary Financial Analysis . .99 District of Columbia Tour Bus Management Initiative 1.0 Introduction: Study Objectives and Technical Approach Washington, DC draws visitors to experience American heritage, culture, and the dynamics of current-day democracy in a setting of majesty and grace befitting a great nation. The tourism and hospitality industry serving these visitors accounts for close to 20 percent of the total workforce in metropolitan Washington.1 Tourism, therefore, is a vital force in the local economy and tour buses, which have been estimated to serve as many as one-third of the visitors to Washington’s historical and cultural attractions, perform a function crucial to both the economic life of the city and its role as the nation’s capital.2 The benefits related to tour bus operations currently come at a significant cost, however. Large numbers of tour buses contribute to traffic congestion on the roadways serving the District and its environs. Several factors compound the adverse traffic impacts associated with tour bus operations. -

H4 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

H4 bus time schedule & line map H4 East To Brookland Station View In Website Mode The H4 bus line (East To Brookland Station) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) East To Brookland Station: 12:26 AM - 11:35 PM (2) West To Tenleytown Station: 12:40 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest H4 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next H4 bus arriving. Direction: East To Brookland Station H4 bus Time Schedule 41 stops East To Brookland Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:28 AM - 11:20 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:35 PM 40th St NW + Albemarle St NW 4001 Albemarle Street Nw, Washington Tuesday 12:26 AM - 11:35 PM Fort Dr + Tenley Circle Wednesday 12:26 AM - 11:35 PM Fort Drive Northwest, Washington Thursday 12:26 AM - 11:35 PM Wisconsin Ave NW + Tenley Circle NW Friday 12:26 AM - 11:35 PM Tenley Circle Northwest, Washington Saturday 12:26 AM - 11:29 PM Wisconsin Ave NW + Van Ness St NW 4130 Wisconsin Avenue Nw, Washington Wisconsin Ave + Upton St X 4005 Wisconsin Avenue Nw, Washington H4 bus Info Direction: East To Brookland Station Wisconsin Ave NW + Rodman St NW Stops: 41 3801 Rodman Street Northwest, Washington Trip Duration: 42 min Line Summary: 40th St NW + Albemarle St NW, Fort Porter St + Wisconsin Ave Dr + Tenley Circle, Wisconsin Ave NW + Tenley Circle 3717 Porter Street Northwest, Washington NW, Wisconsin Ave NW + Van Ness St NW, Wisconsin Ave + Upton St X, Wisconsin Ave NW + Rodman St Porter St + 37th St NW, Porter St + Wisconsin Ave, Porter St + 37th St, 3515 Idaho Avenue