The Evolution of Brotherhood in Crime from Deewaar to Satya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

Kamal's Party to Fight Corruption

The Word Edition 5 Page 1_Layout 1 2/27/2018 10:41 AM Page 1 Volume No 18 Issue No 5 February 23, 2018 LAB JOURNAL OF THE ASIAN COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM Cost of dying in Students fret Artists survive Chennai over NEET in a village Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Kamal’s party to fight corruption PRATIBHA SHARMA felt Haasan’s political venture de - Haasan’s movies, she wouldn’t pended on various factors. vote for him. “He is going to Chennai: Tamil film star Kamal “Kamal’s success in politics de - change once he enters into poli - Haasan launched his political party pends on how attractive or relevant tics,” she said. ‘Makkal Needhi Maiam’ (People’s he is politically. An average voter G.C Shekhar remained sceptical Justice Center) and hoisted the flag likes to vote for a winning candi - of Kamal Haasan’s fanbase turning carrying the party’s symbol at Ot - date rather than a person he likes,” into votes as he believed that he hakadai ground in Madurai on Fe - said G.C Shekhar, a senior journa - had unnecessarily antagonized the bruary 21. list. Hindu fanbase, by making contro - The 63-year-old actor, who is on Duraisamy Ravindaran, a poli - versial statements. a three-day statewide tour, visited tical observer, said “Kamal’s suc - This English speaking middle APJ Abdul Kalam’s home in Ra - cess depends on his political class and the urban population meswaram and spoke about his strategy. So far, he has maintained which comprise the bulk of Haa - entry into politics. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Discourses of Merit and Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Looking Back at the Land: Discourses of Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema and Information Technology Labor Padma Chirumamilla School of Information, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA This article takes Anand Pandian’s notion of “agrarian civility” as a lens through which we can begin to understand the discourses of morality, merit, and exclusivity that color both popular Telugu film and Telugu IT workers’ understanding of their technologically enabled work. Popular Telugu film binds visual qualities of the landscape and depictions of heroic technological proficiency to protagonists’ internal dispositions and moralities. I examine the portrayal of the landscape and of technology in two Telugu films: Dhee … kotti chudu,and Nuvvostanante Nenoddantana, in order to more clearly discern the nature of this agrarian civility and—more importantly for thinking about Telugu IT workers— to make explicit its attribution of morality to “merit” and to technological proficiency. Keywords: Information Technology, Morality, Telugu Cinema, Merit, Agrarian Civility. doi:10.1111/cccr.12144 InachasesceneinthepopularTelugufilmDhee … kotti chudu,anameless gangster—having just killed off his rival’s family—is fleeing to Bangalore from Hyderabad, driving along roads surrounded by rocky, barren outcrops, and shriveled patches of trees. The rival’s boss confronts him unexpectedly on the deserted road, quickly and seemingly instantaneously surrounding him with his own men and vehicles, before killing him in retaliation. The film then quickly moves on to its main character, a rather comedic scam artist, and its main spaces, in the city of Hyderabad.1 This particular stretch of barren landscape—scene to the violence that underlies a significant revenge plot woven into the film’s story—is not returned to. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

D-Company and the 1993 Mumbai Bombings: Rethinking a Case of ‘Crime-Terror Convergence’ in South Asia

Mahadevan – D-company & 1993 Mumbai Bombings 54 The European Review of Organised Crime Original article D-Company and the 1993 Mumbai Bombings: rethinking a case of ‘crime-terror convergence’ in South Asia Prem Mahadevan* Abstract: In 1993, a transnational crime organization known as D-Company carried out mass-casualty terrorist bombings in Mumbai, India. The reasons for this action have been attributed to religious grievances. However, little attention has been given to the role played by Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence in supporting the bombings. Taking into account what has emerged in the public domain over the last 28 years regarding ISI links with D-Company and with international jihadist groups more generally, a re-assessment of the 1993 bombings is required. Hitherto regarded as an example of ‘crime-terror convergence’, it appears that D-Company might be more aptly considered an instrument of covert action. Keywords: Terrorism, heroin, gold, intelligence, covert operations. * Prem Mahadevan is Senior Analyst, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Email: [email protected] The European Review of Organised Crime 6(1), 2021, pp. 54-98. ISSN: 2312-1653 © ECPR Standing Group of Organised Crime. For permissions please email: [email protected] 54 Mahadevan – D-company & 1993 Mumbai Bombings 55 Introduction This article examines why the transnational crime syndicate known as ‘D-Company’ bombed the city of Mumbai in 1993. In what remains the bloodiest-ever terror incident on Indian soil, 257 civilians were killed by 12 near-synchronous explosions. The bombs had been assembled using military-grade explosive smuggled from abroad. The events of that day, Friday 12 March 1993, are considered by scholars as an example of hybridity between organized crime and political terrorism (Rollins, Wyler and Rosen, 2010: 14-16). -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra Land: Indien 2004. Produktion: Yash Raj Films (Mumbai). Regie: Yash Chopra. Buch: Aditya Chopra. Regie Actionszenen: Allan Amin. Kamera: Anil Mehta. Ton: Anuj Mathur. Musik: Madan Mohan. Neueinspielung: Sanjeev Kohli. Arrangements: R.S. Mani. Liedtexte: Javed Akhtar. Sänger: Lata Mangeshkar, Udit Narayan, Sonu Nigam, Roop Kumar Rathod, Gurdas Mann, Ahmed Hussain, Mohammed Hussain, Mohammed Vakil, Javed Hussain, Pritha Majumder. Ausstattung: Sharmishta Roy. Choreographie: Saroj Khan, Vaibhavi Merchant. Kostüme: Manish Malhotra. Beratung (Drehbuch & Ausstattung): Nasreen Rehman. Schnitt: Ritesh Soni. Produzenten: Yash Chopra, Aditya Chopra. Co-Produzenten: Pamela Chopra, Uday Chopra, Payal Chopra. Aufnahmeleitung: Sanjay Shivalkar, Padam Bhushan. Darsteller: Shahrukh Khan (Veer Pratap Singh), Rani Mukerji (Saamiya Siddiqui), Preity Zinta (Zaara), Kirron Kher, Divya Dutta, Boman Irani, Anupam Kher, Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Manoj Bajpai, Zohra Segal (Bebe), S.M. Zaheer (Justice Qureshi), Tom Alter (Dr. Yusuf), Gurdas Mann (als er selbst), Arun Bali (Abdul Mallik Shirazi, Razas Vater), Akhilendra Mishra (Gefängniswärter Majid Khan), Rushad Rana (Saahil), Vinod Negi (Ranjeet), Balwant Bansal (Qazi), Rajesh Jolly (Priester), Anup Kanwal Singh (Sänger), Kanwar Jagdish (Glatzkopf im Bus), Dev K. Kantawalla (Munir), Vicky Ahuja (Vernehmungsbeamtin), Ranjeev Verma (Vernehmungsbeamter), Jas Keerat (Junger Cricket-Spieler), Sanjay Singh Bhadli (Bauer), Kulbir Baderson (Töpferin), Shivaya Singh (Kamli), Huzeifa Gadiwalla -

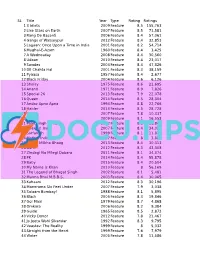

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

Satya 13 Ram Gopal Varma, 1998

THE CINEMA OF INDIA EDITED BY LALITHA GOPALAN • WALLFLOWER PRESS LO NOON. NEW YORK First published in Great Britain in 2009 by WallflowerPress 6 Market Place, London WlW 8AF Copyright © Lalitha Gopalan 2009 The moral right of Lalitha Gopalan to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owners and the above publisher of this book A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-905674-92-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-905674-93-0 (hardback) Printed in India by Imprint Digital the other �ide of 1 TRUTH l Hl:SE\TS IU\ffi(W.\tYEHl\"S 1 11,i:1111111,1:11'1111;1111111 11111111:U 1\ 11.IZII.IH 11.1\lli I 111 ,11 I ISll.lll. n1,11, UH.Iii 236 24 FRAMES SATYA 13 RAM GOPAL VARMA, 1998 On 3 July, 1998, a previously untold story in the form of an unusual film came like a bolt from the blue. Ram Gopal Varma'sSatya was released all across India. A low-budget filmthat boasted no major stars, Satya continues to live in the popular imagination as one of the most powerful gangster filmsever made in India. Trained as a civil engineer and formerly the owner of a video store, Varma made his entry into the filmindustry with Shiva in 1989.