Chesterfield Inlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Victoria's Arctic Fashion Life in Antarctica Racing to Kimmirut

ISSUE 04 Racing to Kimmirut How to Stay Safe and Have Fun on Off-Road Vehicles Life in Antarctica COMIC PREPARING SKINS Victoria’s Arctic Nunavut Fashion Prospectors Takuttalirilli! Editors and Dorothy Milne Jordan Hoffman consultants Pascale Baillargeon Reena Qulitalik Dana Hopkins Caleb MacDonald Emma Renda Designer Larissa MacDonald Rachel Michael Jessie Hale Yulia Mychkina Maren Vsetula Denise Petipas Heather Main Julien Lagarde Nadia Mike Contributors Amanda Sandland Emma Renda Nancy Goupil Ibi Kaslik Dana Hopkins Laura Edlund Alexander Hoffman Department of Education, Government of Nunavut PO Box 1000, Station 960, Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 Design and layout copyright © 2018 Inhabit Education Text copyright © Inhabit Education Images: © Inhabit Media, front cover • © Kingulliit Productions, pages 2–3 • © Alexander Hoffman, pages 4–7 • © Chipmunk131/shutterstock.com, page 8 • © Alfa Photostudio/shutterstock.com, page 9 • © JAYANNPO/shutterstock.com, page 10 • © imageBROKER/alamy.com, page10 • © Rawpixel.com/shutterstock.com, page 11 • © Peyker/shutterstock.com, page 12 • © Department of Family and Services, Government of Nunavut, page 12 • © Everett Historical/shutterstock.com, page 13 • © Mike Beauregard/wikimedia.org, page 14 • © NASA, page 15 • © Sebastian Voortman/pexels.com, page 16 • © Davidee Qaumariaq, page 16 • © CHIARI VFX/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © nobeastsofierce/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Kateryna Kon/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Iasha/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Triff/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Vitaly Korovin/shutterstock.com, page 18 • © Dcrjsr/wikimedia.org, page 20 • © Madlen/shutterstock.com, page 20 • © Olga Strakhova/shutterstock.com, page 20 • © Department of Health, Government of Nunavut, page 21 • © Amanda Sandland, pages 22–25 • © Suzanne Tucker/shutterstock.com, page 26 • © Jenson_P/wikimedia.org, page 28 • © Nowik Sylwia/shutterstock.com, page 29 • © Sherilyn Sewoee, page 31 • © Victoria Kakuktinniq, pages 32–33 • © Toma Feizo Gas, pages 34–40. -

New Constraints on the Age, Geochemistry

New constraints on the age, geochemistry, and environmental impact of High Arctic Large Igneous Province magmatism: Tracing the extension of the Alpha Ridge onto Ellesmere Island, Canada T.V. Naber1,2, S.E. Grasby1,2, J.P. Cuthbertson2, N. Rayner3, and C. Tegner4,† 1 Geological Survey of Canada–Calgary, Natural Resources Canada, Calgary, Canada 2 Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada 3 Geological Survey of Canada–Northern, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa, Canada 4 Centre of Earth System Petrology, Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark ABSTRACT Island, Nunavut, Canada. In contrast, a new Province (HALIP), is one of the least studied U-Pb age for an alkaline syenite at Audhild of all LIPs due to its remote geographic lo- The High Arctic Large Igneous Province Bay is significantly younger at 79.5 ± 0.5 Ma, cation, and with many exposures underlying (HALIP) represents extensive Cretaceous and correlative to alkaline basalts and rhyo- perennial arctic sea ice. Nevertheless, HALIP magmatism throughout the circum-Arctic lites from other locations of northern Elles- eruptions have been commonly invoked as a borderlands and within the Arctic Ocean mere Island (Audhild Bay, Philips Inlet, and potential driver of major Cretaceous Ocean (e.g., the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge). Recent Yelverton Bay West; 83–73 Ma). We propose anoxic events (OAEs). Refining the age, geo- aeromagnetic data shows anomalies that ex- these volcanic occurrences be referred to col- chemistry, and nature of these volcanic rocks tend from the Alpha Ridge onto the northern lectively as the Audhild Bay alkaline suite becomes critical then to elucidate how they coast of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada. -

Geostrategy and Canadian Defence: from C.P. Stacey to a Twenty-First Century Arctic Threat Assessment

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 20, ISSUE 1 Studies Geostrategy and Canadian Defence: From C.P. Stacey to a Twenty-First Century Arctic Threat Assessment Ryan Dean and P. Whitney Lackenbauer1 “If some countries have too much history, we have too much geography.” -- Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1936 Geostrategy is the study of the importance of geography to strategy and military operations. Strategist Bernard Loo explains that “it is the influence of geography on tactical and operational elements of the strategic calculus that underpins, albeit subliminally, strategic calculations about the feasibility of the use of military force because the geographical conditions will influence policy-makers’ and strategic 1 An early version of some sections of this article appeared as “Geostrategical Approaches,” a research report for Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) project on the Assessment of Threats Against Canada submitted in 2015. We are grateful to the coordinators of that project, as well as to reviewers who provided feedback that has strengthened this article. Final research and writing was completed pursuant to a Department of National Defence MINDS Collaborative Network grant supporting the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN). ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2019 ISSN : 1488-559X JOURNAL OF MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES planners’ perceptions of strategic vulnerabilities or opportunities.”2 By extension, the geographical size and location of a country are key determinants -

Proceedings Template

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2020/032 Central and Arctic Region Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area in support of the identification of an Area of Interest T.N. Loewen1, C.A. Hornby1, M. Johnson2, C. Chambers2, K. Dawson2, D. MacDonell2, W. Bernhardt2, R. Gnanapragasam2, M. Pierrejean4 and E. Choy3 1Freshwater Institute Fisheries and Oceans Canada 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 2North/South Consulting Ltd. 83 Scurfield Blvd, Winnipeg, MB R3Y 1G4 3McGill University. 845 Sherbrooke Rue, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4 4Laval University Pavillon Alexandre-Vachon 1045, , av. of Medicine Quebec City, QC G1V 0A6 July 2020 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2020 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Loewen, T. N., Hornby, C.A., Johnson, M., Chambers, C., Dawson, K., MacDonell, D., Bernhardt, W., Gnanapragasam, R., Pierrejean, M., and Choy, E. 2020. Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton proposed Area of Interest for the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. -

Examining Precontact Inuit Gender Complexity and Its

EXAMINING PRECONTACT INUIT GENDER COMPLEXITY AND ITS DISCURSIVE POTENTIAL FOR LGBTQ2S+ AND DECOLONIZATION MOVEMENTS by Meghan Walley B.A. McGill University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2018 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador 0 ABSTRACT Anthropological literature and oral testimony assert that Inuit gender did not traditionally fit within a binary framework. Men’s and women’s social roles were not wholly determined by their bodies, there were mediatory roles between masculine and feminine identities, and role-swapping was—and continues to be—widespread. However, archaeologists have largely neglected Inuit gender diversity as an area of research. This thesis has two primary objectives: 1) to explore the potential impacts of presenting queer narratives of the Inuit past through a series of interviews that were conducted with Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer/Questioning and Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2S+) Inuit and 2) to consider ways in which archaeological materials articulate with and convey a multiplicity of gender expressions specific to pre-contact Inuit identity. This work encourages archaeologists to look beyond categories that have been constructed and naturalized within white settler spheres, and to replace them with ontologically appropriate histories that incorporate a range of Inuit voices. I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, qujannamiik/nakummek to all of the Inuit who participated in interviews, spoke to me about my work, and provided me with vital feedback. My research would be nothing without your input. I also wish to thank Safe Alliance for helping me identify interview participants, particularly Denise Cole, one of its founding members, who has provided me with invaluable insights, and who does remarkable work that will continue to motivate and inform my own. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Volume 12, 1959

THE ARCT IC CIRCLE THE COMMITTEE 1959 Officers President: Dr. D.C. Rose Vice -Presidents Mr. L.A.C.O. Hunt Secretary: Mr. D. Snowden Treasurer: Mr. J .E. Cleland Publications Secretary: Miss Mary Murphy Editor: Mrs .G.W. Rowley Members Mr. Harvey Blandford Mr. Welland Phipps Mr. J. Cantley Mr. A. Stevenson Mr. F..A. Cate Mr. Fraser Symington L/Cdr. J.P. Croal, R.C.N. Mr. J .5. Tener Miss Moira Dunbar Dr. R. Thorsteinsson W IC K. R. Greenaway, R.C.A.F. Dr. J.S. Willis Mr. T .H. Manning Mr. J. Wyatt Mr. Elijah Menarik CONTENTS VOLUME XlI, 1959 NO.1 Meetings of the Arctic Circle 1 Officers and Committee Members for 1959 Z Research in the Lake Hazen region of northern Ellesmere Island in the International Geophysical Year Z Anthropological work in the Eastern Arctic, 1958 13 Geomorphological studies on Southampton Island, 1958 15 Bird Sanctuaries in Southampton Island 17 Subscriptions for 1959 18 Change of Address 18 Editorial Note 18 NO. Z U.S. Navy airship flight to Ice Island T3 19 Firth River archaeological activities. 1956 and 1958 Z6 A light floatplane operation in the far northern islands, 1958 Z9 Change of Address 31 Editorial Note 31 NO.3 Meetings of the Arctic Circle 3Z The Polar Continental Shelf Project, 1959 3Z Jacobsen-McGill Arctic Research Expedition to Axel Heiberg Island 38 Biological work on Prince of Wales Island in the summer of 1958 40 Geographical Branch Survey in southern Melville Peninsula, 1959 43 Pilot of Arctic Canada 48 Subsc riptions for 1960 50 Change of Address 51 • Editorial Note 51 I NO.4 Meetings of the Arctic Circle 52 Officers and Committee Members for 1960 52 Some factors regarding northern oil and gas 53 Nauyopee. -

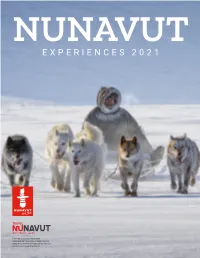

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

Summary of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem Overview

i SUMMARY OF THE HUDSON BAY MARINE ECOSYSTEM OVERVIEW by D.B. STEWART and W.L. LOCKHART Arctic Biological Consultants Box 68, St. Norbert P.O. Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3V 1L5 for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans Central and Arctic Region, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 Draft March 2004 ii Preface: This report was prepared for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Central And Arctic Region, Winnipeg. MB. Don Cobb and Steve Newton were the Scientific Authorities. Correct citation: Stewart, D.B., and W.L. Lockhart. 2004. Summary of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem Overview. Prepared by Arctic Biological Consultants, Winnipeg, for Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Winnipeg, MB. Draft vi + 66 p. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................1 2.0 ECOLOGICAL OVERVIEW.........................................................................................................3 2.1 GEOLOGY .....................................................................................................................4 2.2 CLIMATE........................................................................................................................6 2.3 OCEANOGRAPHY .........................................................................................................8 2.4 PLANTS .......................................................................................................................13 2.5 INVERTEBRATES AND UROCHORDATES.................................................................14 -

Atlantic Walrus Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 23 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Richard, P. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-23 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the status report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Andrew Trites, Co-chair, COSEWIC Marine Mammals Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation du morse de l'Atlantique (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère.