Media Cognizatti: Critical Frames for Free Speech and New Interpretations Brian T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Introduction to Screenwriting 1: the 5 Elements

Introduction to screenwriting 1: The 5 elements by Allen Palmer Session 1 Introduction www.crackingyarns.com.au 1 Can we find a movie we all love? •Avatar? •Lord of the Rings? •Star Wars? •Groundhog Day? •Raiders of the Lost Ark? •When Harry Met Sally? 2 Why do people love movies? •Entertained •Escape •Educated •Provoked •Affirmed •Transported •Inspired •Moved - laugh, cry 3 Why did Aristotle think people loved movies? •Catharsis •Emotional cleansing or purging •What delivers catharsis? •Seeing hero undertake journey that transforms 4 5 “I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive ... ... so that we can actually feel the rapture being alive.” Joseph Campbell “The Power of Myth” 6 What are audiences looking for? • Expand emotional bandwidth • Reminder of higher self • Universal connection • In summary ... • Cracking yarns 7 8 Me 9 You (in 1 min or less) •Name •Day job •Done any courses? Read any books? Written any screenplays? •Have a concept? •Which film would you like to have written? 10 What’s the hardest part of writing a cracking screenplay? •Concept? •Characters? •Story? •Scenes? •Dialogue? 11 Typical script report Excellent Good Fair Poor Concept X Character X Dialogue X Structure X Emotional Engagement X 12 Story without emotional engagement isn’t story. It’s just plot. 13 Plot isn’t the end. It’s just the means. 14 Stories don’t happen in the head. They grab us by the heart. 15 What is structure? •The craft of storytelling •How we engage emotions •How we generate catharsis •How we deliver what audiences crave 16 -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface ASBJØRN GRØNSTAD Consider this paradox: in Howard Hawks' Scarface, The Shame of the Nation, violence is virtually all-encompassing, yet it is a film from an era before American movies really got violent. There are no graphic close-ups of bullet wounds or slow-motion dissection of agonized faces and bodies, only a series of abrupt, almost perfunctory liquidations seemingly devoid of the heat and passion that characterize the deaths of the spastic Lyle Gotch in The Wild Bunch or the anguished Mr. Orange, slowly bleeding to death, in Reservoir Dogs. Nonetheless, as Bernie Cook correctly points out, Scarface is the most violent of all the gangster films of the eatly 1930s cycle (1999: 545).' Hawks's camera desists from examining the anatomy of the punctured flesh and the extended convulsions of corporeality in transition. The film's approach, conforming to the period style of ptc-Bonnie and Clyde depictions of violence, is understated, euphemistic, in its attention to the particulars of what Mark Ledbetter sees as "narrative scarring" (1996: x). It would not be illegitimate to describe the form of violence in Scarface as discreet, were it not for the fact that appraisals of the aesthetics of violence are primarily a question of kinds, and not degrees. In Hawks's film, as we shall see, violence orchestrates the deep structure of the narrative logic, yielding an hysterical form of plotting that hovers between the impulse toward self- effacement and the desire to advance an ethics of emasculation. Scarface is a film in which violence completely takes over the narrative, becoming both its vehicle and its determination. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2016 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 9 Photography Workshops 10 Loans 11 Objects Loaned for Exhibitions 11 Film Screenings 15 Acquisitions 17 Gifts to the Collections 17 Photography 17 Moving Image 22 Technology 23 George Eastman Legacy 24 Purchases for the Collections 29 Photography 29 Technology 30 Conservation & Preservation 31 Conservation 31 Photography 31 Moving Image 36 Technology 36 George Eastman Legacy 36 Richard & Ronay Menschel Library 36 Preservation 37 Moving Image 37 Financial 38 Treasurer’s Report 38 Fundraising 40 Members 40 Corporate Members 43 Matching Gift Companies 43 Annual Campaign 43 Designated Giving 45 Honor & Memorial Gifts 46 Planned Giving 46 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 47 Board of Trustees 47 George Eastman Museum Staff 48 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2016. Alvin Langdon Coburn Sight Reading: ONGOING Curated by Pamela G. Roberts and organized for Photography and the Legible World From the Camera Obscura to the the George Eastman Museum by Lisa Hostetler, Curated by Lisa Hostetler, Curator in Charge, Revolutionary Kodak Curator in Charge, Department of Photography Department of Photography, and Joel Smith, Curated by Todd Gustavson, Curator, Technology Main Galleries Richard L. Menschel -

Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 49/Thursday, March 13

11974 Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 49 / Thursday, March 13, 2003 / Rules and Regulations a designee, and is a thorough review of DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION LIBRARY OF CONGRESS the case. The formal review determination shall be based on the Saint Lawrence Seaway Development 36 CFR Part 704 information, upon which the initial Corporation determination and/or reconsideration National Film Preservation Board; determination was based, and any 33 CFR Part 401 1994–2002 Films Selected for Inclusion additional information the appealing in the National Film Registry party may submit or OCHAMPUS may [Docket No. SLSDC 2002–13698] AGENCY: National Film Preservation obtain. Board, Library of Congress. (3) Timeliness of formal review RIN 2135–AA15 ACTION: Final rule. determination. The Chief, Office of SUMMARY: The Librarian of Congress is Appeals and Hearings, OCHAMPUS, or Seaway Regulations and Rules: publishing the following list of films a designee normally shall issue the Automatic Identification System formal review determination no later selected from 1994–2002 for inclusion in the National Film Registry in the than 90 days from the date of receipt of AGENCY: Saint Lawrence Seaway Library of Congress pursuant to section the request for formal review by the Development Corporation, DOT. OCHAMPUS. 103 of the National Film Preservation (4) Notice of formal review ACTION: Final rule; correction. Act of 1996. The films are published to determination. The Chief, Office of notify the public of the Librarian’s Appeals and Hearings, OCHAMPUS, or SUMMARY: In the Saint Lawrence Seaway selection of twenty-five films selected in a designee shall issue a written notice Development Corporation (SLSDC) final each of these years deemed to be of the formal review determination to rule amending the Seaway regulations ‘‘culturally, historically or aesthetically the appealing party at his or her last and rules (33 CFR part 401) published significant’’ in accordance with known address. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Predator Collection Inventory NECA Item Series Have Wish List Wolf

Predator Collection Inventory NECA Item Series Have Wish List Wolf Masked AVP-R Wolf Masked Battle Damage AVP-R Wolf Open Mouth AVP-R Wolf Closed Mouth AVP-R Wolf Open Moth Battle Dam. AVP-R Wolf Cloaked AVP-R Wolf Mid-Cloak SDCC 2008 Falconer Predators series 1 Berzerker Predators series 1 Berzerker Un-masked Predators series 2 Predators Hound Predators series 3 Tracker Predators series 2 Berzerker Camo-Cloaked TRU 2-pack w/ City Hunter (A) Berzerker Cloaked SDCC 2010 Classic Battle Damaged Predators series 2 Classic Un-masked Predators series 1 Classic closed mouth 2-pack w/ Alien Warrior (B) Classic Masked Predators series 3 Classic Gort SDCC 2011 Classic Cloaked TRU Exclusive City Hunter Cloaked SDCC 2012 Elder (V1) Predators series 3 City Hunter TRU 2-pack w/ Berzerker (A) Shaman Predators series 4 City Hunter Un-masked Predators series 4 Boar Predators series 4 Stalker Predators series 5 Snake Predators series 5 Guardian (Gort) Predators series 5 Warrior Predators series 6 Lost Predators series 6 Scout Predators series 6 Falconer Camo-Cloaked Predators series 7 Big Red Predators series 7 City Hunter Masked Predators series 7 Jungle Hunter Battle Damage TRU 2-pack w/ City Hunter ( C) City Hunter Battle Damage TRU 2-pack w/ Jungle Hunter ( C) Dutch Jungle Extraction Predators series 8 Jungle Hunter Masked Predators series 8 Dutch Jungle Patrol Predators series 8 Dutch Jungle Encounter Predators series 9 Jungle Hunter Water Emergence Predators series 9 Dutch Jungle Disguise Predators series 9 Albino SDCC 2013 Dutch Final Battle TRU -

Land Rover Kabini 3.Indd

SPECIAL FEATURE SPECIAL FEATURE “ oo!”. Silence. Absolute silence. planet’s riches. Today, he’s spent the “I see you” without so much as a, “Hey “Aoo!”.Spotted deer raising the afternoon stalking his current obsession – there!”. Crossing the road, it disappears Aalarm. ‘A big cat’s here and we Nagarhole’s lone black panther. The word into the undergrowth. The light, too, can smell it.’ “Haarh!” “Haarh!” Barking panther, mind you, is used as a synonym seems to fade with it, and no amount of deer, calling out up ahead, adding to for leopard and for one with a genetic waiting, circling back to the regular haunts the warnings signalled by their genetic mutation that occurs rarely but naturally of the panther produces result. cousins. The driver nudges the idling in the wild. It renders the animal’s coat a So, it’s back to The Bison, the luxury TRACKING THE vehicle closer to the source of the shade of black. The spots become visible lodge Shaaz’s parents founded in 2010, sound. More alarm calls. The langurs in Shaaz’s high-resolution imagery. Given which he now runs. Shaaz’s home for join in. “It has to be close by,” whispers its colour and because of how difficult it is much of the year, The Bison is a luxurious PANTHER OF NAGARHOLE Shaaz. “Langurs call only when they to track and spot the animal (there’s just African-style, tented camp, built on the can see the predator and that’s within one in all of the park’s 643sqkm area), banks of the Kabini dam’s backwaters. -

THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL and DISTRICT 9 a Thes

WHEN YOU CAN’T “PHONE HOME”: SUBVERSIVE POLITICS OF THE FOREIGN OTHER IN E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL AND DISTRICT 9 A Thesis By SAMANTHA GENE HARVEY Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2017 Department of English WHEN YOU CAN’T “PHONE HOME”: SUBVERSIVE POLITICS OF THE FOREIGN OTHER IN E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL AND DISTRICT 9 A Thesis by SAMANTHA GENE HARVEY MAY 2017 APPROVED BY: Başak Çandar, Ph.D. Chairperson, Thesis Committee Germán Campos-Muñoz, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Kyle Stevens, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Carl Eby, Ph.D. Chairperson, Department of English Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Samantha Gene Harvey 2017 All Rights Reserved Abstract WHEN YOU CAN’T “PHONE HOME”: SUBVERSIVE POLITICS OF THE FOREIGN OTHER IN E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL AND DISTRICT 9 Samantha Gene Harvey B.A., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Başak Çandar, Ph.D. This thesis takes a close look at the ways in which alien representations, especially in films, mirror the ways in which transnational and migrant individuals are viewed and treated by the majority populations of already established nations. By tracing the history of science fiction, the connotations that the genre makes and the ways in which extraterrestrial narratives comment on reality can be evaluated in detail. The subversive politics that are created by such narratives, both intentionally and unwittingly, contributes to the perceptions of the Other that are embraced by the oppressive masses and which perpetuate certain types of treatment. -

1 What Follows Is a List of Films That Are

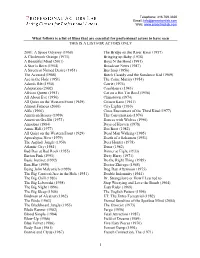

Telephone: 416.769.3320 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proactroslab.com What follows is a list of films that are essential for professional actors to have seen THIS IS A LIST FOR ACTORS ONLY 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) A Clockwork Orange (1971) Bringing up Baby (1938) A Beautiful Mind (2001) Boyz N the Hood (1991) A Star is Born (1954) Broadcast News (1987) A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) Bus Stop (1956) The Accused (1988) Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) Ace in the Hole (1951) The Caine Mutiny (1954) Adam's Rib (1950) Carrie (1976) Adaptation (2002) Casablanca (1943) African Queen (1951) Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) All About Eve (1950) Chinatown (1974) All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) Citizen Kane (1941) Almost Famous (2000) City Lights (1930) Alfie (1966) Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) American Beauty (1999) The Conversation (1974) American Graffiti (1973) Dances with Wolves (1990) Amadeus (1984) Days of Heaven (1978) Annie Hall (1977) Das Boot (1982) All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) Dead Man Walking (1995) Apocalypse Now (1979) Death of a Salesman (1951) The Asphalt Jungle (1950) Deer Hunter (1978) Atlantic City (1981) Diner (1982) Bad Day at Bad Rock (1955) Dinner at Eight (1933) Barton Fink (1991) Dirty Harry (1971) Basic Instinct (1992) Do the Right Thing (1989) Ben-Hur (1959) Doctor Zhivago (1965) Being John Malcovich (1999) Dog Day Afternoon (1975) The Big Carnival/Ace in the Hole (1951) Double Indemnity (1944) The Big Chill (1983) Dr. -

The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel

The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel Edited by Elizabeth Mannion General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14927 Elizabeth Mannion Editor The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel Editor Elizabeth Mannion Philadelphia , Pennsylvania , USA Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-53939-7 ISBN 978-1-137-53940-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-53940-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933996 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or here- after developed.