Matters of Hand: Craft, Design and Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. What Comprises Foreign Goods?

1. WHAT COMPRISES FOREIGN GOODS? A gentleman asks: “Should we boycott all foreign goods or only some select ones?” This question has been asked many times and I have answered it many times. And the question does not come from only one person. I face it at many places even during my tour. In my view, the only thing to be boycotted thoroughly and despite all hardships is foreign cloth, and that can and should be done through khadi alone. Boycott of all foreign things is neither possible nor proper. The difference between swadeshi and foreign cannot hold for all time, cannot hold even now in regard to all things. Even the swadeshi character of khadi is due to circumstances. Suppose there is flood in India and only one island remains on which a few persons alone survive and not a single tree stands; at such a time the swadeshi dharma of the marooned would be to wear what clothes are provided and eat what food is sent by generous people across the sea. This of course is an extreme instance. So it is for us to consider what our swadeshi dharma is. Today many things which we need for our sustenance and which are not imposed upon us come from abroad. As for example, some of the foreign medicines, pens, needles, useful tools, etc., etc. But those who wear khadi and consider it an honour or are not ashamed to have all other things of foreign make fail to understand the significance of khadi. The significance of khadi is that it is our dharma to use those things which can be or are easily made in our country and on which depends the livelihood of poor people; the boycott of such things and deliberate preference of foreign things is adharma. -

CASE NO. 22 of 2000 and 25 of 2000 ORDER

BEFORE THE HON’BLE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION AT AHMEDABAD CASE NO. 22 OF 2000 and 25 of 2000 Date: 1st December 2001 CORAM JUSTICE S.D.DAVE, Chairman SHRI B.M. OZA, Member SHRI R.K.SHARMA, Member In the matter of the application filed by the Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce & Industry and others (No. 22 of 2000) and In the matter of the application filed by Southern Gujarat Texturising Association (No. 25 of 2000) ORDER Introduction 1. The Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce and Industry had filed a petition on 28/7/2000 in the matter of Special Power Tariff for Power loom Segment of Textiles Industry falling in the category of SSI/ Tiny sector. The other applicant, along with Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce and Industry were Surat Artsilk Cloth Manufacturing Association, Surat Vankar Sahakari Sangh Ltd, Shri Udhna Group Weavers’ Co-op. Society Limited, Sasme Co-Operative Society Ltd, The Surat Weavers Co-op. Producers’ Society Ltd, Surat Grey Kapad Page 1 of 18 Utpadak Sangh, Kim Pipodara Weavers Association & Ved Road Art Silk Laghu Udyog Weaving Association. After registering the application, the notices were issued to the State of Gujarat, Gujarat Electricity Board, Surat Electricity Co. Ltd and Ahmedabad Electricity Company Limited. The hearing was held on 3/11/2000 at Surat. Amendment to the application 2. In the beginning of the hearing Shri I.J Desai, learned Advocate for the main applicant Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce and Industry submitted an application for amendment to relief clause No. 6(a) of the application already given. -

Kala Cotton: a Sustainable Alternative Banhi Jha, National Institute of Fashion Technology, India the Asian Conference on Sustai

Kala Cotton: A Sustainable Alternative Banhi Jha, National Institute of Fashion Technology, India The Asian Conference on Sustainability, Energy & the Environment 2018 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract Further to the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future (1987) this paper extends the model of sustainable practices of ‘interconnecting people, processes and environment’ (Hethorn and Ulasewicz 2008) to the cotton-growing farmer community and users of cotton among organizations and Indian designers. Presently, 96% of India's cotton cultivation is under Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) cotton crops, the first genetically modified crop to be approved for cultivation in India in 2002. While introduction of Bt cotton led to a dramatic increase in production across cotton producing states, there have also been controversies regarding allegations that it has spurred farmer suicides in the country, thereby pointing to the unsustainability of these genetically modified seeds. The greatest sustainability challenges for cotton cultivation are to reduce pesticides, fertilizers and water use while promoting better working conditions and financial returns for farmers. Organic cotton cultivation is a system that does not use synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, growth regulators or defoliants. Kala cotton is an indigenous, organic, rain-fed crop growing in eastern Kutch, Gujarat. This species of cotton offers obvious benefits including healthier soil quality and place less demand on the scarce water resources. In order to explore the possibilities of Kala cotton, some non-governments organizations (NGOs) are engaging with farmers to research about the crop to facilitate collaborations with weavers. Some fashion designers, online crafts and even a large textile mill are using Kala cotton for fashion apparel. -

Salt Satyagraha the Watershed

I VOLUME VI Salt Satyagraha The Watershed SUSHILA NAYAR NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD-380014 MAHATMA GANDHI Volume VI SALT SATYAGRAHA THE WATERSHED By SUSHILA NAYAR First Edition: October 1995 NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD 380014 MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org The Salt Satyagraha in the north and the south, in the east and the west of India was truly a watershed of India's history. The British rulers scoffed at the very idea of the Salt March. A favourite saying in the barracks was: "Let them make all the salt they want and eat it too. The Empire will not move an inch." But as the Salt Satyagraha movement reached every town and village and millions of people rose in open rebellion, the Empire began to shake. Gandhi stood like a giant in command of the political storm. It was not however only a political storm. It was a moral and cultural storm that rose from the inmost depths of the soul of India. The power of non-violence came like a great sunrise of history. ... It was clear as crystal that British rule must give way before the rising tide of the will of the people. For me and perhaps for innumerable others also this was at the same time the discovery of Gandhi and our determination to follow him whatever the cost. (Continued on back flap) MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org By Pyarelal The Epic Fast Status of Indian Princes A Pilgrimage for Peace A Nation-Builder at Work Gandhian Techniques in the Modern World Mahatma Gandhi -The Last Phase (Vol. -

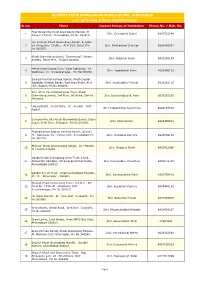

Adress Khadi 6-5-11-1-For-Pdf.Xlsx

GUJARAT RAJYA KHADI GRAMODHYOG BOARD, AHMEDABAD LIST OF KHADI & POLY INSTITUTIONS Sr.no.Name Contact Person of Institution Phone No. / Mob. No. Bhal Nalkantha Khadi Gramodyog Mandal, At 1 Shri. Govindsinh Dabhi 9427322794 Ranpur, District: Ahmedabad, Pin No.363610. Jari Resham Khadi Gramodyog Sangh, 9-1452- 253, Khapatiya Chakla, At & Dist: Surat, Pin Shri. Girdharbhai Chauhan 9898486851 No.395003. Khadi Gramodyog Sangh, "Samanway", Jayant 3 Shri. Ajaybhai Doshi 9427268109 Society, Mavdi Plot, Rajkot-360004. Mehta Khadi Udyog Gruh, Vikas Vidhyalay, At : 4 Shri. Jagdishbhai Dave 9825496128 Wadhwan, Di : Surendranagar, Pin No.363030. Saurashtra Rachnatmak Samiti, Sheth Darbar 5Gopaldas Smarak Bavan, Rashtriya Shala, At & Shri. Harshadbhai Trivedi 9426252115 Dist: Rajkot, Pin No.360002. Smt. M. N. Patel Mahila Vikas Trust, Khadi 6Gramodyog Samiti, 2nd Floor, At Unjha, District: Shri. Balchandbhai N. Patel 9537257203 Mehsana. Udyog Bharti, Chordi Gate, At : Gondal Dist: 7 Shri. Prakashbhai Panchmiya 9898293580 Rajkot. Banaskantha Jilla Khadi Gramodyog Sangh, Super 8 Shri. Sitarambhai 9428485081 Bazar, Delhi Gate, Palanpur, Pin No.385001. Bhalnalkantha Saghan Kshetra Samiti, (Gundi) 9At : Rampura, Ta : Detroj, Dist: Ahmedabad, Pin Shri. Chikabhai Kanotra 9925689168 No.382140. Bhimani Khadi Gramoudyog Sangh, At : Mandvi, 10 Smt. Mayaben Bhatt 9427012966 Di : Kutch-370465. Gandhi Khadi Gramodyog Seva Trust, 13/14, 11Ashwarath Complex, Ushamanpura Char Rasta, Shri. Dalsangbhai Chaudhari 9426873748 Ahmedabad-380013. Gandhi Smruti Trust, Khadi Gramodyog Bhandar, 12 Shri. Devchandbhai Patel 9427755412 At : Di : Bhavnagar - 364001. Ghanad Khadi Gramodyog Trust, G.I.D.C., 4th 13Ploat No. 1930, At : Wadhwan, Dist: Shri. Rupabhai Vaghela 9979448192 Surendranagar, Pin No.363031. Gir Vikas Mandal, At : Una, Dist: Junagadh, Pin 14 Shri. -

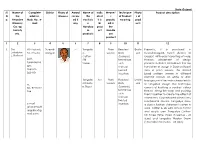

State-Gujarat Sl. N O. Name of the Awardee Weaver

State-Gujarat Sl. Name of Complete District Photo of Award Name of Indic Weave/ Technique Photo Product description N the address, Weaver receiv the ate if s of Product s of o. Awardee Mob. No., e- ed if exclusiv it is practic weaving prod Weaver/ mail any e GI ed in ucts Co.-op Handloo prod the Society m uct Handlo etc. products om product 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1. Shri Vill-Vastadi, Surendr -- Tangaliy _ Plain Beaded Enclo Presently, it is practiced in Jahabhai Ta. Chuda, anagar a weave Dots sed Surendranagar& Kutch districts of L. Rathod Cotton (Danaas) Gujarat. With exact counting of warp Distt. Silk technique threads, placement of design Surenderna Saree with patterns in dots is calculated. It is the gar, manual translation of design in Daana (Bead) Gujarat- twisted form in plain weave. The dotted 363410 insertion bead pattern woven in different contrast colours on white or dark Tangaliy Yes Plain Beaded Enclo background is the main characteristic aWoolle weave Dots sed of Tangaliya design. The technique M. n Shawl (Danaas) No.:9723222 consists of knotting a contrast colour technique 744 thread, along the warp and pushing with them together to create the effect of manual raised dots. It is produced without any twisted mechanical device. Tangaliya now- e-mail- insertion a-days is fashion statement woven in jaharathodt wool, cotton & silk with dots in cotton angaliya@g and acrylic yarn. Tangaliya Cotton- mail.com Silk Saree (Time taken to weave - 25 days) and Tangaliya Woolen Shawl (Time taken to weave - 03 days) Sl. -

A Study on Vernacular Cotton Textiles of Gujarat

PACHHEDI- A STUDY ON VERNACULAR COTTON TEXTILES OF GUJARAT Researcher: Ms. Shrutisingh Tomar Guide: Dr. Madhu Sharan Department of Clothing and Textiles Faculty of Family and Community Sciences The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara 1. INTRODUCTION: Indian textiles have had a celebrated tradition that has fascinated the world for more than two thousand years. By being domicile to the variety of fibers, fabrics, and patterning techniques, it had manufactured matchless quality of woven, embroidered, dyed, printed and painted textiles in the past. The origin of weaving and patterning fabrics in India was directly connected with cotton. Though the manufacture of silk and wool was known in India since the ancient times, the production of cotton cloth was India’s oldest tradition. Cotton was grown, spun, woven, patterned, used in and exported from India in proto-historic times. Vedic and Buddhist Literature, in general, have innumerable references to the art of carding, spinning, weaving and patterning of textiles. The process of weaving cloth was often used as the metaphor for describing cosmic ideas. The terminology for weaving and basketry work was more or less the same in Vedic literature. Certain terms that played a basic role in the early philosophy e.g. guna, tarka or those related to forms of literature such as grantha, sutra, tantra, has, weaved were derived from textile terminology. The present tradition of hand-woven cotton textiles have evidently descended from the proto-historic prototypes. For historical, economic and climatic reasons, cotton has also been the single most popular textile type of this country (Ed. Singh M. -

Chapter: Ii Historical and Geographical Background

CHAPTER: II HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF THE RESEARCH FIELD (AREA) (INTRODUCATION OF THE RESEARCH AREA (FIELD)) Sr. No. Details Page No. 2.1 Introduction 89 2.2 Historical and Geographical Introduction to Gujarat 89-129 2.3 Historical and Geographical Introduction to Ahmedabad 129-141 District 2.4 Historical and Geographical Introduction to Bhal-Nalkantha 141-207 area 2.5 Conclusion 207-208 References 209 83 CHAPTER: II HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF THE RESEARCH FIELD (AREA) (INTRODUCATION OF THE RESEARCH AREA (FIELD)) Sr. No. Details Page No. 2.1 Introduction 89 2.2 Historical and Geographical Introduction to Gujarat 89-129 2.2.1 Historical Introduction to Gujarat 89-97 2.2.2 Geographical Introduction to Gujarat 97-99 2.2.2.1 Geography 99-103 2.2.2.2 Location (Borders) 103-104 2.2.2.3 Land 104-105 2.2.2.4 Natural Divisions 105 2.2.2.4.1 North Gujarat Division 105 2.2.2.4.2 South Gujarat Division 105 2.2.2.4.3 Central Gujarat 105-106 2.2.2.4.4 Saurashtra and Kutch area 106 2.2.2.5 Minerals 106 2.2.2.6 Forest and Forest area 106-109 2.2.2.7 Mountains 109-111 2.2.2.8 Climate, Temperature and Rain 111-112 2.2.2.9 Rivers 112-114 2.2.2.10 Religions 114 2.2.2.11 Languages 114 2.2.2.12 Facts and Figures 114-121 2.2.2.13 Glory of Gujarat (Important Places of Gujarat) 121 2.2.2.13.1 Architectural and Historical Places 121 2.2.2.13.2 Holiday Camps and Picnic Spots 121 2.2.2.13.3 Pilgrim Centres 121-122 2.2.2.13.4 Handicrafts 122 84 2.2.2.13.5 Hill Resorts 122 2.2.2.13.6 Hot Water Springs 122 2.2.2.13.7 Lakes 122 2.2.2.13.8 -

SACRIFICE, AHIMSA, and VEGETARIANISM: POGROM at the DEEP END of NON-VIOLENCE Volume I

SACRIFICE, AHIMSA, AND VEGETARIANISM: POGROM AT THE DEEP END OF NON-VIOLENCE Volume I A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi January 2006 ©2006 Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi SACRIFICE, AHIMSA, AND VEGETARIANISM: POGROM AT THE DEEP END OF NON-VIOLENCE Parvis Ghassem-Fachandi, PhD. Cornell University 2006 This dissertation explores the relation of ahimsa (non-violence) and vegetarianism to sacrificial logic in post-independence Ahmedabad. It follows the transformation of ahimsa--from a protection of the sacrifier against the revenge of the animal victim; to a doctrine of renunciation, self-reform, and prohibition of animal sacrifice; to Gandhi’s famous tool for nonviolent resistance to colonial domination; and finally, to the ritualization of violence itself in the organized persecution of minorities in a secular state. Central Gujarat is often called the “laboratory of Hindutva.” Hindutva offers an interpretation of “Hinduism” as a historical subject threatened by Islam and Christianity. It portrays Hindus as victims of Muslim barbarism, slaughtered and humiliated, butchered and raped, and demands a response that redefines the relation of violence to ahimsa. Its electoral success can be traced to a claim to unify Adivasi, lower, and intermediary caste groups with the Savarnas (high castes) as “Hindus” in opposition to Muslims and Christians, who are positioned as foreigners. As ethno-religious identifications have become integral to representation in a secular democratic system, traditional practices relating to diet and worship are simultaneously reconfigured. This research investigates the embodiment and experience of disgust among members of upwardly mobile castes, who are encouraged both to externalize their own low caste practices and to distance themselves from Muslims and Christians in new ways. -

Apprenticing with the Last Makers of the Milkman's Dress L Ghai Ma 2014

DON’T CRY OVER SPILT MILK: APPRENTICING WITH THE LAST MAKERS OF THE MILKMAN’S DRESS L GHAI MA 2014 DON’T CRY OVER SPILT MILK: APPRENTICING WITH THE LAST MAKERS OF THE MILKMAN’S DRESS LOKESH GHAI A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Master of Arts (By Research) Manchester Institute for Research and Innovation in Art and Design (MIRIAD) 2014 i Abstract The kediyun is an upper garment worn by men in pastoral communities in Kutch, West India. The garment is always white, attracting one's attention with its dramatic and elaborate cut. Traditionally, local women make them for the men in their family, more recently however, tailors have started making them. The research investigates the technique of constructing the kediyun. During the research I initiated three apprenticeships as a method of gaining a comprehensive understanding of the making of the kediyun. This allowed me to hand-make the kediyun and to immerse myself in the domestic environment of traditional makers. Traditional methods of measuring the body for garment construction, which had not been previously detailed, were studied during the apprenticeships. This led me to understand that each kediyun is specific to the maker’s body. The practice-led study of the kediyun, documented in the thesis in the form of still photographs and film, illuminates how the construction of a traditional Indian garment is an extension of the maker’s culture. This notion had largely been ignored in previous publications of stitched Indian garments. During the research, cultural aspects such as folk songs and religious and spiritual beliefs were recognised as informing the making process of the kediyun. -

Natural Colorants: Historical, Processing and Sustainable Prospects

Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. DOI 10.1007/s13659-017-0119-9 REVIEW ARTICLE Natural Colorants: Historical, Processing and Sustainable Prospects Mohd Yusuf . Mohd Shabbir . Faqeer Mohammad Received: 11 November 2016 / Accepted: 2 January 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract With the public’s mature demand in recent times pressurized the textile industry for use of natural colorants, without any harmful effects on environment and aquatic ecosystem, and with more developed functionalities simultaneously. Advanced developments for the natural bio-resources and their sustainable use for multifunctional clothing are gaining pace now. Present review highlights historical overview of natural colorants, classification and predominantly processing of colorants from sources, application on textiles surfaces with the functionalities provided by them. Chemistry of natural colorants on textiles also discussed with relevance to adsorption isotherms and kinetic models for dyeing of textiles. Graphical Abstract Keywords Natural colorants Á Textiles Á Sustainability Á Processing Á Adsorption Á Application M. Yusuf (&) F. Mohammad Department of Chemistry, Y.M.D. College, Maharshi Dayanand e-mail: [email protected] University, Nuh, Haryana 122107, India e-mail: [email protected] M. Shabbir Á F. Mohammad Department of Chemistry, Jamia Millia Islamia (A Central University), New Delhi 110025, India e-mail: [email protected] 123 M. Yusuf et al. 1 Introduction Western countries to exploit their high technical skills in the advancements of textile materials for high quality, Nature has always dominated over synthetic or artificial, technical performances, and side by side development of from the beginning of this world as nature was the only cleaner production strategies for cost-effective value added option for human being then, and now with advantageous textile products [8]. -

Homes of Capital: Merchants and Mobility Across Indian Ocean Gujarat

Homes of Capital: Merchants and Mobility across Indian Ocean Gujarat by Ketaki Pant Department of History Duke University Date: _________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Supervisor ___________________________ Sumathi Ramaswamy __________________________ Janet Ewald __________________________ Philip J. Stern __________________________ Ajantha Subramanian Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT Homes of Capital: Merchants and Mobility across Indian Ocean Gujarat by Ketaki Pant Department of History Duke University Date: _________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Supervisor ___________________________ Sumathi Ramaswamy __________________________ Janet Ewald __________________________ Philip J. Stern __________________________ Ajantha Subramanian An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Ketaki Pant 2015 ABSTRACT HOMES OF CAPITAL: MERCHANTS AND MOBILITY ACROSS INDIAN OCEAN GUJARAT Chair: Engseng Ho My dissertation project is an ethnographic history of “homes of capital,” merchant homes located in port-cities of Gujarat in various states of splendor and decrepitude, which continue to mark a long history of Indian Ocean cross-cultural trade and exchange. Located in western South Asia, Gujarat is a terraqueous borderland, connecting the western and eastern arenas of the Indian Ocean at the same time as it connects territorial South Asia to maritime markets. Gujarat’s dynamic port-cities, including Rander, Surat and Bombay, were and continue to be home to itinerant merchants, many with origins and investments around the littoral from Arabia to Southeast Asia.