SACRIFICE, AHIMSA, and VEGETARIANISM: POGROM at the DEEP END of NON-VIOLENCE Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH

NUMBER 46 2017 GAJAHJournal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group GAJAH Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group Number 46 (2017) The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and conservation of Asian elephants both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by which everyone concerned with the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), whether members of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group or not, can communicate their research results, experiences, ideas and perceptions freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the Asian Elephant Specialist Group. Editor Dr. Jennifer Pastorini Centre for Conservation and Research 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Julpallama, Tissamaharama Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Dr. Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando School of Geography Centre for Conservation and Research University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Kajang, Selangor Julpallama, Tissamaharama Malaysia Sri Lanka e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Varun R. Goswami Heidi Riddle Wildlife Conservation Society Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary 551, 7th Main Road P.O. Box 715 Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, 2nd Phase, Kodigehall Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058 Bengaluru - 560 097 USA India e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr. T. N. C. Vidya -

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

61 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

61 bus time schedule & line map 61 Gujarat High Court View In Website Mode The 61 bus line (Gujarat High Court) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Gujarat High Court: 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM (2) Maninagar Terminus: 8:40 AM - 8:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 61 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 61 bus arriving. Direction: Gujarat High Court 61 bus Time Schedule 25 stops Gujarat High Court Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Monday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Maninagar Railway Crossing Wednesday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Thursday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Friday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Pushpkunj Saturday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Nilamkunj Shah Alam Toll Naka Bhula Bhai Park 61 bus Info Direction: Gujarat High Court S.T. Stand Stops: 25 Trip Duration: 43 min Astodia Chakla Line Summary: Maninagar, Maninagar Railway Crossing, Jawahar Chowk, Pushpkunj, Nilamkunj, Shah Alam Toll Naka, Bhula Bhai Park, S.T. Stand, Khamasa Astodia Chakla, Khamasa, Lal Darwaja, Jansatta O∆ce, Delhi Darwaja, Gandhi Bridge, Income Tax Lal Darwaja O∆ce, Usmanpura, Shri Niketan Society, Naranpura Cross Road, Naranpura, Sola Housing, Bhuyangdev, Jansatta O∆ce Satadhar Cross Road, Sola Police Chowki, Ramdev Masala, Gujarat High Court Brts Delhi Darwaja Gandhi Bridge Income Tax O∆ce Usmanpura Shri Niketan Society Naranpura Cross Road Naranpura Sola Housing Bhuyangdev Satadhar Cross Road Sola Police Chowki Ramdev Masala Gujarat High Court Brts -

1 How to Reach Us Getting to IIMA Ahmedabad Is Well Connected With

How to Reach us Getting to IIMA Ahmedabad is well connected with all the metropolises in India via Air, Trains and Roads. Travelling to Ahmedabad The Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport serves both domestic and international traffic for the city and the neighbouring cities of Gandhinagar, Mehsana and Nadiad. The airport connects the city with destinations across India and to cities in the Middle East, the Far East and select destinations in Western Europe. There are more than 6 flights on a daily basis to Mumbai and Delhi - which are the main international air gateways in and out of India. Delhi is 1.5 hours away by air and Mumbai 50 minutes. Daily flights are also available for Bangalore, Hyderabad, Pune, Chennai and Kolkatta. Domestic Airlines Air India ( www.airindia.com ) Jet Airways ( www.jetairways.com ) Jet Lite (www.jetlite.com ) Kingfisher Airlines ( www.flykingfisher.com ) SpiceJet ( www.spicejet.com ) GoAir ( www.goair.in ) Indigo (www.goindigo.in) International Airlines Air India ( www.airindia.com) Emirates (www.emirates.com ) Singapore Airlines ( www.singaporeair.com ) Air Arabia (www.airarabia.com) Lufthansa (www.lufthansa.com) Qatar Airways (www.qatarairways.com) Time taken from airport to IIMA:30-40 minutes Distance between airport and IIMA:15 km Taxi charges from airport to IIMA:INR 330 1 Trains Please check the Indian Railways website www.indianrail.gov.in for details on train time tables, accommodation availability and fares. You can also book train tickets online using your Credit Card or Online Direct Banking at www.irctc.co.in. Time taken from railway station to IIMA:25-35 minutes Distance between railway station and IIMA:9 km Taxi charges from railway station to IIMA:INR 180 Road National Highway No. -

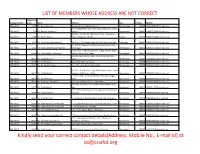

Kindly Send Your Correct Contact Details(Address, Mobile No., E-Mail Id) at [email protected] LIST of MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT

LIST OF MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT Membersh Category Name ip No. Name Address City PinCode EMailID IND_HOLD 6454 Mr. Desai Shamik S shivalik ,plot No 460/2 Sector 3 'c' Gandhi Nagar 382006 [email protected] Aa - 33 Shanti Nath Apartment Opp Vejalpur Bus Stand IND_HOLD 7258 Mr. Nevrikar Mahesh V Vejalpur Ahmedabad 380051 [email protected] Alomoni , Plot No. 69 , Nabatirtha , Post - Hridaypur , IND_HOLD 9248 Mr. Halder Ashim Dist - 24 Parganas ( North ) Jhabrera 743204 [email protected] IND_HOLD 10124 Mr. Lalwani Rajendra Harimal Room No 2 Old Sindhu Nagar B/h Sant Prabhoram Hall Bhavnagar 364002 [email protected] B-1 Maruti Complex Nr Subhash Chowk Gurukul Road IND_HOLD 52747 Mr. Kalaria Bharatkumar Popatlal Memnagar Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] F/ 36 Tarun - Nagar Society Part - 2 Opp Vishram Nagar IND_HOLD 66693 Mr. Vyas Mukesh Indravadan Gurukul Road, Mem Nagar, Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] 8, Keshav Kunj Society, Opp. Amar Shopping Centre, IND_HOLD 80951 Mr. Khant Shankar V Vatva, Ahmedabad 382440 [email protected] IND_HOLD 83616 Mr. Shah Biren A 114, Akash Rath, C.g. Road, Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 84519 Ms. Deshpande Yogita A - 2 / 19 , Arvachin Society , Bopal Ahmedabad 380058 [email protected] H / B / 1 , Swastick Flat , Opp. Bhawna Apartment , Near IND_HOLD 85913 Mr. Parikh Divyesh Narayana Nagar Road , Paldi Ahmedabad 380007 [email protected] 9 , Pintoo Flats , Shrinivas Society , Near Ashok Nagar , IND_HOLD 86878 Ms. Shah Bhavana Paldi Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 89412 Mr. Shah Rajiv Ashokbhai 119 , Sun Ville Row Houses , Mem Nagar , Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] B4 Swetal Park Opp Gokul Rowhouse B/h Manezbaug IND_HOLD 91179 Mr. -

Backyard Farming and Slaughtering 2 Keeping Tradition Safe

Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Bangkok, 2021 FAO. 2021. Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe. Food safety technical toolkit for Asia and the Pacific No. 2. Bangkok. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non- commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. -

ANIMAL SACRIFICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION The

CHAPTER FOURTEEN ANIMAL SACRIFICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION JOANN SCURLOCK The relationship between men and gods in ancient Mesopotamia was cemented by regular offerings and occasional sacrifices of ani mals. In addition, there were divinatory sacrifices, treaty sacrifices, and even "covenant" sacrifices. The dead, too, were entitled to a form of sacrifice. What follows is intended as a broad survey of ancient Mesopotamian practices across the spectrum, not as an essay on the developments that must have occurred over the course of several millennia of history, nor as a comparative study of regional differences. REGULAR OFFERINGS I Ancient Mesopotamian deities expected to be fed twice a day with out fail by their human worshipers.2 As befitted divine rulers, they also expected a steady diet of meat. Nebuchadnezzar II boasts that he increased the offerings for his gods to new levels of conspicuous consumption. Under his new scheme, Marduk and $arpanitum were to receive on their table "every day" one fattened ungelded bull, fine long fleeced sheep (which they shared with the other gods of Baby1on),3 fish, birds,4 bandicoot rats (Englund 1995: 37-55; cf. I On sacrifices in general, see especially Dhorme (1910: 264-77) and Saggs (1962: 335-38). 2 So too the god of the Israelites (Anderson 1992: 878). For specific biblical refer ences to offerings as "food" for God, see Blome (1934: 13). To the term tamid, used of this daily offering in Rabbinic sources, compare the ancient Mesopotamian offering term gimi "continual." 3 Note that, in the case of gods living in the same temple, this sharing could be literal. -

TRULY GLOBAL Worldscreen.Com *LIST 1217 ALT 2 LIS 1006 LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 2

*LIST_1217_ALT 2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM DECEMBER 2017 ASIA TV FORUM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION TRULY GLOBAL WorldScreen.com *LIST_1217_ALT 2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/15/17 2:06 PM Page 2 2 TV LISTINGS ASIA TV FORUM EXHIBITOR DIRECTORY COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR THE COMPANIES IN BOLD CAN BE FOUND IN THIS EDITION OF TV LISTINGS. 9 Story Media Group J30 Fuji Creative Corporation A24-4 Pilgrim Pictures E08/H08 A Little Seed E08/H08 Gala Television Corporation D10 Pixtrend J10 A+E Networks G20 Global Agency E27 Playlearn Media L10 Aardman K32 Globo C30 Premiere Entertainment F34 Aasia Productions E08/H08 GMA Worldwide J01 Primeworks Distribution E30 AB International Distribution E10/F10 Goquest Media Ventures D29 Public Television Service Foundation D10 ABC Commercial L08 Grafizix J10 Rainbow E23 ABC Japan A24-15 Green Gold Animation G30 Rajshri Entertainment L28 About Premium Content E10/F10 Green Yapim N10 Raya Group H07 ABS-CBN Corporation J18 Greener Grass Production D10 Record TV K22 activeTV Asia E08/H08 H Culture J10 Red Arrow International H25 ADK/NAS/D-Rights A24-5 Happy Dog TV L10 Reel One Entertainment K32 AK Entertainment H10/H20 HARI International E10/F10 Refinery Media E08/H08 Alfred Haber Distribution F30 Hasbro Studios F28 Regentact F32 all3media international K08 Hat Trick International K32 Resimli Filim N10 Ampersand E10/F10 Hello Earth B25 Rive Gauche Television J28 Animasia Productions E30 High Commission of Canada H29 RKD Studios L30 Antares International -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

Y1 Q2 9-12.Pdf

Balagokulam Syllabus April - June Age Group : 9 to 12 Gokulam is the place where Lord Krishna‛s magical days of childhood were spent. It was here that his divine powers came to light. Every child has that spark of divinity within. Bala- Gokulam is a forum for children to discover and manifest that divinity. It will enable Hindu children in US to appreciate their cultural roots and learn Hindu values in an enjoyable manner. This is done through weekly gatherings and planned activities which include games, yoga, stories, shlokas, bhajan, arts and crafts and much more...... Balagokulam is a program of Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) Table of Contents April Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ....................................5 Geet ........................................................................................6 Yugadi ....................................................................................7 Stories of Dr. Hedgewar .......................................................10 The Hindu Calendar .............................................................13 Exercise ................................................................................16 Project / Workshop - Art of Story Telling ............................19 May Shloka / Subhashitam / Amrutvachan ..................................20 Geet ......................................................................................21 Symbols in Hinduism ...........................................................22 The Life of Buddha ..............................................................26 -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Congratulations!

Congratulations! JULY 2021 - New World Team A V INDDU , KANCHIPURAM ABAJI KHANVILKAR ANITA , MUMBAI ADHIKARI MADHUMITA & PATIT PABAN ADHIKARI, BIRBHUM ADIB HUTAIB , RAIGARH MH ADRI PANKAJA & CHANDRAKANT ADRI, BAGALKOT AGARKAR SHITAL PANKAJ , AMRAVATI AGARWAL ANKIT , JAIPUR AGARWAL REENA , JAIPUR AGGARWAL LAVI & ANKUR AGARWAL, SAHARANPUR AGLAWE SAMPADA ARUN & ARUN EKNATH AGALAVE, THANE AGRAWAL AMIT KUMAR & PURNIMA AGRAWAL, PATAN AGRAWAL SHEETAL , SAMBALPUR AGRAWAL SWETA & ROHIT AGRAWAL, SULTANPUR AHAMED B ZAMEER , HOSPET AHMED MOHAMMAD AKHIL , UDUPI AHMED RAEES & NASEEM BEGAM, NAINITAL AHMED TAFHEEM , BHADERWAH DODA AHUJA MALA & SANJAY AHUJA, YAMUNA NAGAR AJAYKUMAR CK & SUPRIYA M, DODDABALLAPUR ALAGURAJ POOMALAI & A DEIVAM, PUDUKKOTTAI ALI KHAN SORAF & TANUJA BEGUM, HOOGHLY ALI MOHAMMED SHOUKATH & SHANAZ BANU, DAVANGERE ALLIBHAI ABBASALI DAVALASAB , GADAG ALTHAF S , PUNGANUR AMBADAS PAWAR PRATIKSHA , AURANGABAD AMLA ASHISH , JAMMU ANANDHARAJ C , NAGAPATTINAM ANKUR , BHARATPUR ANU , TOHANA APPAJI TARATE MADHUKAR , PHALTAN ARCHANA & HARDEEP KUMAR, AHMEDABAD ARORA PALAK , JALLANDHAR ARUN KAMBLE ANITA & ARUN HARIBHAU KAMBLE, SANGLI ARVIND PAWAR KAVITA , AHMED NAGAR ASAD RABIA & ABBAS ASAD, LUCKNOW ASHFAK M M & SAFRINA, KASARGOD ASHIMA & PARVESH KUMAR ASPAL, JALANDHAR ASHTARIAN SAMAANEH & MOHAMMED MESUM ABU, KHAIRATABAD ASMABI , PONNANI AWATE NARENDRA CHANDRAKANT , PUNE B AMARESH & VIJAYLAXMI, RAICHUR BAANGA SONIA , FARIDKOT BABAIAH DUDEKULA & VAHIDA BANU DUDEKULA, CUDDAPAH BABU V J PRASANTH & REJITHA, NEDUMANGAD BABULAL , HANUMANGARH Congratulations!