Mycobiota in the Carposphere of Sour and Sweet Cherries and Antagonistic Features of Potential Biocontrol Yeasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deuteromycota Phylum: Deuteromycota Commonly Referred to As the Fungi Imperfecti Or Imperfect Fungi

Deuteromycota Phylum: Deuteromycota Commonly referred to as the Fungi Imperfecti or imperfect fungi. Classification based on asexual stage because: Sexual reproduction rare, occurs only in narrow environmental parameters. Sexual phase of life cycle no longer exist. Phylum: Deuteromycota Phylum: Deuteromycota Only asexual reproduction occurs, typically conidia borne on When mycelial septate. conidiophores. Thallus also may be yeast or dimorphic. Classified according to conidia color, When sexual reproduction discovered, shape, size and number of septa. usually an Ascomycota or less often Form taxon: An artificial classification Basidiomycota. scheme. When sexual reproduction discovered, usually an Ascomycota or less often Basidiomycota. Purpose of Deuteromycota Purpose of Deuteromycota Division was erected to accommodate Instead, recall example of Emericella conidia producing fungi with unknown variecolor (=Aspergillus variecolor). sexual cycle. When sexual stage discovered, Emericella variecolor, the sexual species would be reclassified stage is the telomorph. according to sexual stage. Aspergillus variecolor, the asexual In practice this concept did not work. stage is the anamorph. Thus, sexual stage is often present. 1 Defining Taxa in Deuteromycota Taxonomy of Deuteromycota based mostly on spore morphology Saccardoan System of spore Saccardoan System of classification. Oldest system of defining taxa in Spore Classification. fungi. Artificial means of classification. No longer used in other taxa. Amerosporae: Conidia one celled, Didymosporae: Conidia Ovoid sphaerical, ovoid to elongate or to oblong, one septate short cylindric. Allantosporae: Conidia bean- Hyalodidymospore: shaped, hyaline Conidia Hyaline. to dark. Phaeodidymospore: Hyalosporae: Conidia dark. Conidia hyaline Phaeosporae: Conidia dark. Phragmosporae: Conidia oblong, Dictyosporae: Conidia ovoid to two to many transverse septa oblong, transversely and longitudinally septate. Hyalophramospore: Conidia hyaline. -

Whole Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomic Analysis Of

Li et al. BMC Genomics (2020) 21:181 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-6593-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Whole genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis of oleaginous red yeast Sporobolomyces pararoseus NGR identifies candidate genes for biotechnological potential and ballistospores-shooting Chun-Ji Li1,2, Die Zhao3, Bing-Xue Li1* , Ning Zhang4, Jian-Yu Yan1 and Hong-Tao Zou1 Abstract Background: Sporobolomyces pararoseus is regarded as an oleaginous red yeast, which synthesizes numerous valuable compounds with wide industrial usages. This species hold biotechnological interests in biodiesel, food and cosmetics industries. Moreover, the ballistospores-shooting promotes the colonizing of S. pararoseus in most terrestrial and marine ecosystems. However, very little is known about the basic genomic features of S. pararoseus. To assess the biotechnological potential and ballistospores-shooting mechanism of S. pararoseus on genome-scale, the whole genome sequencing was performed by next-generation sequencing technology. Results: Here, we used Illumina Hiseq platform to firstly assemble S. pararoseus genome into 20.9 Mb containing 54 scaffolds and 5963 predicted genes with a N50 length of 2,038,020 bp and GC content of 47.59%. Genome completeness (BUSCO alignment: 95.4%) and RNA-seq analysis (expressed genes: 98.68%) indicated the high-quality features of the current genome. Through the annotation information of the genome, we screened many key genes involved in carotenoids, lipids, carbohydrate metabolism and signal transduction pathways. A phylogenetic assessment suggested that the evolutionary trajectory of the order Sporidiobolales species was evolved from genus Sporobolomyces to Rhodotorula through the mediator Rhodosporidiobolus. Compared to the lacking ballistospores Rhodotorula toruloides and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we found genes enriched for spore germination and sugar metabolism. -

Red Pigmented Basidiomycete Mirror Yeast of the Phyllosphere Alec Cobban1, Virginia P

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Revisiting the pink- red pigmented basidiomycete mirror yeast of the phyllosphere Alec Cobban1, Virginia P. Edgcomb1, Gaëtan Burgaud2, Daniel Repeta3 & Edward R. Leadbetter1 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 2Université de Brest, EA 3882, Laboratoire Universitaire de Biodiversité et Ecologie Microbienne, ESIAB, Technopôle Brest-Iroise, Plouzané 29280, France 3Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 Keywords Abstract Ballistospore, D1/D2, phylogeny, physiology, rRNA, Sporobolomyces. By taking advantage of the ballistoconidium-forming capabilities of members of the genus Sporobolomyces, we recovered ten isolates from deciduous tree Correspondence leaves collected from Vermont and Washington, USA. Analysis of the small Virginia P. Edgcomb, Department of Geology subunit ribosomal RNA gene and the D1/D2 domain of the large subunit and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic ribosomal RNA gene indicate that all isolates are closely related. Further analysis Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543. of their physiological attributes shows that all were similarly pigmented yeasts Tel: +1-508-289-3734; Fax: 508-457-2183; E-mail: [email protected] capable of growth under aerobic and microaerophilic conditions, all were toler- ant of repeated freezing and thawing, minimally tolerant to elevated temperature Funding Information and desiccation, and capable of growth in liquid or on solid media -

Competing Sexual and Asexual Generic Names in <I

doi:10.5598/imafungus.2018.09.01.06 IMA FUNGUS · 9(1): 75–89 (2018) Competing sexual and asexual generic names in Pucciniomycotina and ARTICLE Ustilaginomycotina (Basidiomycota) and recommendations for use M. Catherine Aime1, Lisa A. Castlebury2, Mehrdad Abbasi1, Dominik Begerow3, Reinhard Berndt4, Roland Kirschner5, Ludmila Marvanová6, Yoshitaka Ono7, Mahajabeen Padamsee8, Markus Scholler9, Marco Thines10, and Amy Y. Rossman11 1Purdue University, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, West Lafayette, IN 47901, USA; corresponding author e-mail: maime@purdue. edu 2Mycology & Nematology Genetic Diversity and Biology Laboratory, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA 3Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Geobotanik, ND 03/174, D-44801 Bochum, Germany 4ETH Zürich, Plant Ecological Genetics, Universitätstrasse 16, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland 5Department of Biomedical Sciences and Engineering, National Central University, 320 Taoyuan City, Taiwan 6Czech Collection of Microoorganisms, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic 7Faculty of Education, Ibaraki University, Mito, Ibaraki 310-8512, Japan 8Systematics Team, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 9Staatliches Museum f. Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Erbprinzenstr. 13, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany 10Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt (Main), Germany 11Department of Botany & Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97333, USA Abstract: With the change to one scientific name for pleomorphic fungi, generic names typified by sexual and Key words: asexual morphs have been evaluated to recommend which name to use when two names represent the same genus Basidiomycetes and thus compete for use. In this paper, generic names in Pucciniomycotina and Ustilaginomycotina are evaluated pleomorphic fungi based on their type species to determine which names are synonyms. Twenty-one sets of sexually and asexually taxonomy typified names in Pucciniomycotina and eight sets in Ustilaginomycotina were determined to be congeneric and protected names compete for use. -

Forming Yeast Genus Sporobolomyces Based on 18S Rdna Sequences

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2000), 50, 1373–1380 Printed in Great Britain Phylogenetic analysis of the ballistoconidium- forming yeast genus Sporobolomyces based on 18S rDNA sequences Makiko Hamamoto and Takashi Nakase Author for correspondence: Makiko Hamamoto. Tel: j81 48 467 9560. Fax: j81 48 462 4617. e-mail: hamamoto!jcm.riken.go.jp Japan Collection of The 18S rDNA nucleotide sequences of 25 Sporobolomyces species and five Microorganisms, The Sporidiobolus species were determined. Those of Sporobolomyces dimmenae Institute of Physical and T T Chemical Research (RIKEN), JCM 8762 , Sporobolomyces ruber JCM 6884 , Sporobolomyces sasicola JCM Wako, Saitama 351-0198, 5979T and Sporobolomyces taupoensis JCM 8770T showed the presence of Japan intron-like regions with lengths of 1586, 324, 322 and 293 nucleotides, respectively, which were presumed to be group I introns. A total of 63 18S rDNA nucleotide sequences was analysed, including 33 published reference sequences. Sporobolomyces species and the other basidiomycetes species were distributed throughout the phylogenetic tree. The resulting phylogeny indicated that Sporobolomyces is polyphyletic. Sporobolomyces species were mainly divided into four groups within the Urediniomycetes. The groups are designated as the Sporidiales, Agaricostilbum/Bensingtonia, Erythrobasidium and subbrunneus clusters. The last group, comprising four species, Sporobolomyces coprosmicola, Sporobolomyces dimmenae, Sporobolomyces linderae and Sporobolomyces subbrunneus, forms a new and distinct cluster in the phylogenetic tree in this study. Keywords: ballistoconidium-forming yeasts, phylogeny, rDNA, Sporobolomyces INTRODUCTION myces cerevisiae) of 49 ballistoconidium-forming yeasts and related non-ballistoconidium-forming Members of the genus Sporobolomyces (Kluyver & van yeasts. This work indicated that Sporobolomyces Niel, 1924) are anamorphic basidiomycetous yeasts, species were widely dispersed on the phylogenetic tree. -

The Phylogeny of Plant and Animal Pathogens in the Ascomycota

Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology (2001) 59, 165±187 doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0355, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on MINI-REVIEW The phylogeny of plant and animal pathogens in the Ascomycota MARY L. BERBEE* Department of Botany, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada (Accepted for publication August 2001) What makes a fungus pathogenic? In this review, phylogenetic inference is used to speculate on the evolution of plant and animal pathogens in the fungal Phylum Ascomycota. A phylogeny is presented using 297 18S ribosomal DNA sequences from GenBank and it is shown that most known plant pathogens are concentrated in four classes in the Ascomycota. Animal pathogens are also concentrated, but in two ascomycete classes that contain few, if any, plant pathogens. Rather than appearing as a constant character of a class, the ability to cause disease in plants and animals was gained and lost repeatedly. The genes that code for some traits involved in pathogenicity or virulence have been cloned and characterized, and so the evolutionary relationships of a few of the genes for enzymes and toxins known to play roles in diseases were explored. In general, these genes are too narrowly distributed and too recent in origin to explain the broad patterns of origin of pathogens. Co-evolution could potentially be part of an explanation for phylogenetic patterns of pathogenesis. Robust phylogenies not only of the fungi, but also of host plants and animals are becoming available, allowing for critical analysis of the nature of co-evolutionary warfare. Host animals, particularly human hosts have had little obvious eect on fungal evolution and most cases of fungal disease in humans appear to represent an evolutionary dead end for the fungus. -

Downloaded from by IP: 199.133.24.106 On: Mon, 18 Sep 2017 10:43:32 Spatafora Et Al

UC Riverside UC Riverside Previously Published Works Title The Fungal Tree of Life: from Molecular Systematics to Genome-Scale Phylogenies. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4485m01m Journal Microbiology spectrum, 5(5) ISSN 2165-0497 Authors Spatafora, Joseph W Aime, M Catherine Grigoriev, Igor V et al. Publication Date 2017-09-01 DOI 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0053-2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Fungal Tree of Life: from Molecular Systematics to Genome-Scale Phylogenies JOSEPH W. SPATAFORA,1 M. CATHERINE AIME,2 IGOR V. GRIGORIEV,3 FRANCIS MARTIN,4 JASON E. STAJICH,5 and MEREDITH BLACKWELL6 1Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; 2Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907; 3U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA 94598; 4Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Unité Mixte de Recherche 1136 Interactions Arbres/Microorganismes, Laboratoire d’Excellence Recherches Avancés sur la Biologie de l’Arbre et les Ecosystèmes Forestiers (ARBRE), Centre INRA-Lorraine, 54280 Champenoux, France; 5Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology and Institute for Integrative Genome Biology, University of California–Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521; 6Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 and Department of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208 ABSTRACT The kingdom Fungi is one of the more diverse INTRODUCTION clades of eukaryotes in terrestrial ecosystems, where they In 1996 the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae was provide numerous ecological services ranging from published and marked the beginning of a new era in decomposition of organic matter and nutrient cycling to beneficial and antagonistic associations with plants and fungal biology (1). -

Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (Eds A

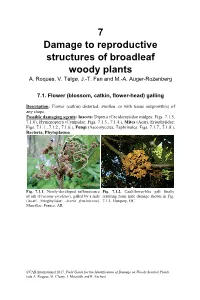

7 Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants A. Roques, V. Talgø, J.-T. Fan and M.-A. Auger-Rozenberg 7.1. Flower (blossom, catkin, flower-head) galling Description: Flower (catkin) distorted, swollen, or with tissue outgrowth(s) of any shape. Possible damaging agents: Insects: Diptera (Cecidomyiidae midges: Figs. 7.1.5, 7.1.6), Hymenoptera (Cynipidae: Figs. 7.1.3., 7.1.4.), Mites (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Figs. 7.1.1., 7.1.2., 7.1.6.), Fungi (Ascomycetes, Taphrinales: Figs. 7.1.7., 7.1.8.), Bacteria, Phytoplasma. Fig. 7.1.1. Newly-developed inflorescence Fig. 7.1.2. Cauliflower-like gall finally of ash (Fraxinus excelsior), galled by a mite resulting from mite damage shown in Fig. (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Aceria fraxinivora). 7.1.1. Hungary, GC. Marcillac, France, AR. ©CAB International 2017. Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (eds A. Roques, M. Cleary, I. Matsiakh and R. Eschen) Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants 71 Fig. 7.1.3. Berry-like gall on a male catkin Fig. 7.1.4. Male catkin of Quercus of oak (Quercus sp.) caused by a gall wasp myrtifoliae, deformed by a gall wasp (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Neuroterus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Callirhytis quercusbaccarum). Hungary, GC. myrtifoliae). Florida, USA, GC. Fig. 7.1.5. Inflorescence of birch (Betula sp.) Fig. 7.1.6. Symmetrically swollen catkin of deformed by a gall midge (Diptera, hazelnut (Corylus sp.) caused by a gall Cecidomyiidae: Semudobia betulae). midge (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae: Contarinia Hungary, GC. coryli) or a gall mite (Acari Eriophyiidae: Phyllocoptes coryli). -

ISSN 2320-9186 Β-Carotene—Properties and Production Method from the Yeasts Alaa

GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 2317 GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2021, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com β-Carotene—properties and production method from The Yeasts Alaa Hussein Ali College of Science/Biology Dept. Univ. of Mosul Email : [email protected] Abstract Carotenoids are natural stains produced by different groups of living organisms, such as plants, animals, and micro-organisms. They take many colors, such as yellow, orange, red, and purple. Microorganisms have received a lot of attention from researchers to obtain carotenoids from their natural sources, as they are characterized by the easy of extraction and purification, low costs, and production is not related to the seasonal changes experienced by the process of extracting carotene from plants, in addition to that carotene The output has no negative effects. Carotenoids are of great importance and have wide applications in many areas because of their functions and properties that made them interesting, as they play a role in protecting cells from the harmful effects of free radicals and reducing the risk of injury Some types of cancerous diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and the prevention of Alzhemeir's disease due to its antioxidant properties and carotenoids are also included in the food industry as they are used as food colorants that contribute to attracting consumers to goods and goods and are added as food supplements to animal feed and recently entered the pharmaceutical industries. Introduction Carotenoids are a group of natural dyes produced by a group a wide variety of plants, algae, and microorganisms such as bacteria, molds, and yeasts (Perez-Fons et al., 2011). -

A Higher-Level Phylogenetic Classification of the Fungi

mycological research 111 (2007) 509–547 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mycres A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi David S. HIBBETTa,*, Manfred BINDERa, Joseph F. BISCHOFFb, Meredith BLACKWELLc, Paul F. CANNONd, Ove E. ERIKSSONe, Sabine HUHNDORFf, Timothy JAMESg, Paul M. KIRKd, Robert LU¨ CKINGf, H. THORSTEN LUMBSCHf, Franc¸ois LUTZONIg, P. Brandon MATHENYa, David J. MCLAUGHLINh, Martha J. POWELLi, Scott REDHEAD j, Conrad L. SCHOCHk, Joseph W. SPATAFORAk, Joost A. STALPERSl, Rytas VILGALYSg, M. Catherine AIMEm, Andre´ APTROOTn, Robert BAUERo, Dominik BEGEROWp, Gerald L. BENNYq, Lisa A. CASTLEBURYm, Pedro W. CROUSl, Yu-Cheng DAIr, Walter GAMSl, David M. GEISERs, Gareth W. GRIFFITHt,Ce´cile GUEIDANg, David L. HAWKSWORTHu, Geir HESTMARKv, Kentaro HOSAKAw, Richard A. HUMBERx, Kevin D. HYDEy, Joseph E. IRONSIDEt, Urmas KO˜ LJALGz, Cletus P. KURTZMANaa, Karl-Henrik LARSSONab, Robert LICHTWARDTac, Joyce LONGCOREad, Jolanta MIA˛ DLIKOWSKAg, Andrew MILLERae, Jean-Marc MONCALVOaf, Sharon MOZLEY-STANDRIDGEag, Franz OBERWINKLERo, Erast PARMASTOah, Vale´rie REEBg, Jack D. ROGERSai, Claude ROUXaj, Leif RYVARDENak, Jose´ Paulo SAMPAIOal, Arthur SCHU¨ ßLERam, Junta SUGIYAMAan, R. Greg THORNao, Leif TIBELLap, Wendy A. UNTEREINERaq, Christopher WALKERar, Zheng WANGa, Alex WEIRas, Michael WEISSo, Merlin M. WHITEat, Katarina WINKAe, Yi-Jian YAOau, Ning ZHANGav aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA bNational Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, -

Collecting and Recording Fungi

British Mycological Society Recording Network Guidance Notes COLLECTING AND RECORDING FUNGI A revision of the Guide to Recording Fungi previously issued (1994) in the BMS Guides for the Amateur Mycologist series. Edited by Richard Iliffe June 2004 (updated August 2006) © British Mycological Society 2006 Table of contents Foreword 2 Introduction 3 Recording 4 Collecting fungi 4 Access to foray sites and the country code 5 Spore prints 6 Field books 7 Index cards 7 Computers 8 Foray Record Sheets 9 Literature for the identification of fungi 9 Help with identification 9 Drying specimens for a herbarium 10 Taxonomy and nomenclature 12 Recent changes in plant taxonomy 12 Recent changes in fungal taxonomy 13 Orders of fungi 14 Nomenclature 15 Synonymy 16 Morph 16 The spore stages of rust fungi 17 A brief history of fungus recording 19 The BMS Fungal Records Database (BMSFRD) 20 Field definitions 20 Entering records in BMSFRD format 22 Locality 22 Associated organism, substrate and ecosystem 22 Ecosystem descriptors 23 Recommended terms for the substrate field 23 Fungi on dung 24 Examples of database field entries 24 Doubtful identifications 25 MycoRec 25 Recording using other programs 25 Manuscript or typescript records 26 Sending records electronically 26 Saving and back-up 27 Viruses 28 Making data available - Intellectual property rights 28 APPENDICES 1 Other relevant publications 30 2 BMS foray record sheet 31 3 NCC ecosystem codes 32 4 Table of orders of fungi 34 5 Herbaria in UK and Europe 35 6 Help with identification 36 7 Useful contacts 39 8 List of Fungus Recording Groups 40 9 BMS Keys – list of contents 42 10 The BMS website 43 11 Copyright licence form 45 12 Guidelines for field mycologists: the practical interpretation of Section 21 of the Drugs Act 2005 46 1 Foreword In June 2000 the British Mycological Society Recording Network (BMSRN), as it is now known, held its Annual Group Leaders’ Meeting at Littledean, Gloucestershire. -

A Survey of Ballistosporic Phylloplane Yeasts in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2012 A survey of ballistosporic phylloplane yeasts in Baton Rouge, Louisiana Sebastian Albu Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Albu, Sebastian, "A survey of ballistosporic phylloplane yeasts in Baton Rouge, Louisiana" (2012). LSU Master's Theses. 3017. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3017 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF BALLISTOSPORIC PHYLLOPLANE YEASTS IN BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana Sate University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Plant Pathology by Sebastian Albu B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2001 B.S., Metropolitan University of Denver, 2005 December 2012 Acknowledgments It would not have been possible to write this thesis without the guidance and support of many people. I would like to thank my major professor Dr. M. Catherine Aime for her incredible generosity and for imparting to me some of her vast knowledge and expertise of mycology and phylogenetics. Her unflagging dedication to the field has been an inspiration and continues to motivate me to do my best work.