Ghana Armed Forces MOWIP REPORT 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter JULY 2021

NewsLetter JULY 2021 HIGHLIGHTS UN provides independent monitoring young people’s businesses support to Ghana’s 2021 Population Supporting the national COVID-19 and Housing Census. UN supports the establishment of a response is core to our development Coordinated Mechanism on the Safety efforts. Youth Innovation for Sustainable De- of Journalists. velopment Challenge gives a boost to United Nations in Ghana - April - June 2021 COVID-19 RESPONSE Supporting the national COVID-19 response: Core to UN’s development efforts management, logistics, data the fight against the pandem- Ghana received its sec- management and operation- ic. Through the efforts of the ond batch of the AstraZen- al plans, field support super- United Nations Development eca COVID-19 vaccine from vision, and communications Programme (UNDP), medical the COVAX facility on 7th May and demand creation activities. supplies from the West African 2021. With this delivery of Health Organisation (WAHO) 350,000 doses, many Ghana- UNICEF conducted three sur- have been delivered. Funded by ians who received their first veys on knowledge, attitudes the German Government (BMZ), dose were assured of their and practices around COVID-19 the European Union, the Econom- second jab. The UN Children’s vaccination through telephone ic Community of West African Fund (UNICEF) facilitated their interviews and mobile interactive States (ECOWAS) and WAHO, safe transport from the Dem- voice responses across different these set of supplies, the second ocratic Republic of Congo. key groups. Per the survey, key bulk supplies to ECOWAS mem- concerns on vaccine hesitancy ber states, was procured by GIZ Since the launch of the vac- are around safety, efficacy and and UNDP. -

Irish All-Army Champions 1923-1995

Irish All-Army Champions 1923-1995 To be forgotten is to die twice Most Prolific All Army Individual Titles Name Command Disciplines Number of individual titles Capt Gerry Delaney Curragh Command Sprints 30 Pte Jim Moran Ordnance Service Jumps, Hurdles 25 Capt Mick O' Farrell Curragh Command Throws, Jumps, Hurdles 19 Capt Billy McGrath Curragh Command Throws 17 Comdt Bernie O' Callaghan Eastern Command Walks 17 Cpl Brendan Downey Curragh Command Middle Distance, C/C 17 C/S Frank O' Shea Curragh Command Throws 16 Comdt Kevin Humphries Air Corps Middle Distance,C/C 16 Pte Tommy Nolan Curragh Command Jumps, Hurdles 15 Comdt JJ Hogan Curragh Command Throws 14 Capt Tom Ryan Eastern Command Hurdles, Pole Vault 14 Cpl J O'Driscoll Curragh Command Weight Throw 14 C/S Tom Perch Southern Command Throws 13 Pte Sean Carlin Western Command FCA Jumps, Throws 13 Capt Junior Cummins Southern Command Middle Distance 13 Capt Dave Ashe Curragh Command Jumps, Sprints 13 CQMS Willy Hyland Southern Command Hammer 12 Capt Jimmy Collins Ordnance Service 440,880, 440 Hurdles 11 Capt Gerry N Coughlan Western Command 220,440,880, Mile 11 Capt Pat Healy Curragh Command pole Vault, Throws 11 Sgt Paddy Murphy Curragh Command 5,000m, C/C 11 CQMS Billy Hyland Southern Command Hammer 11 Sgt J O'Driscoll Curragh Command 56 Lb W.F 14 Notable Athletes who won Irish All Army Championshiups Name / Command About 1st All Army title Capt Gerry N Coughlan, Western Command Olympian 1924 Tpr Noel Carroll, Eastern Command Double Olympian 1959 Pte Danny McDaid, Eastern Command FCA -

Address to the Nation by President of the Republic, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, on Updates to Ghana's Enhanced Response to Th

ADDRESS TO THE NATION BY PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC, NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO, ON UPDATES TO GHANA’S ENHANCED RESPONSE TO THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC, ON SUNDAY, 5TH APRIL, 2020. Fellow Ghanaians, Good evening. Nine (9) days ago, I came to your homes and requested you to make great sacrifices to save lives, and to protect our motherland. I announced the imposition of strict restrictions to movement, and asked that residents of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area and Kasoa and the Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Area and its contiguous districts to stay at home for two (2) weeks, in order to give us the opportunity to stave off this pandemic. As a result, residents of these two areas had to make significant adjustments to our way of life, with the ultimate goal being to protect permanently our continued existence on this land. They heeded the call, and they have proven, so far, to each other, and, indeed, to the entire world, that being a Ghanaian means we look out for each other. Yes, there are a few who continue to find ways to be recalcitrant, but the greater majority have complied, and have done so with calm and dignity. Tonight, I say thank you to each and every one of you law-abiding citizens. Let me thank, in particular, all our frontline actors who continue to put their lives on the line to help ensure that we defeat the virus. To our healthcare workers, I say a big ayekoo for the continued sacrifices you are making in caring for those infected with the virus, and in caring for the sick in general. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

Draft Agenda JULY Kempinski Gold Coast Accra 2019 Accra, Ghana

International Maritime Defense Exhibition and Conference HOSTED BY : 23-25 Draft Agenda JULY Kempinski Gold Coast Accra 2019 Accra, Ghana VVIP Attendees DR MAHAMUDU BAWUMIA HON. DOMINIC ADUNA BINGAB NITIWUL LT. GEN. OBED AKWA MAJ GEN WILLIAM AZURE AYAMDO R/ ADM SETH AMOAMA AIR VICE MARSHAL F HANSON VICE PRESIDENT OF MINISTER OF DEFENCE, GHANA CHIEF OF DEFENCE STAFF CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF CHIEF OF NAVAL STAFF CHIEF OF AIR STAFF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA GHANA ARMED FORCES GHANA ARMY GHANA NAVY GHANA AIRFORCE ORGANISED BY : www.imdecafrica.com Event overview The inaugural International Maritime Defence Exhibition and Conference (IMDEC) will feature the largest gathering of Africa’s maritime stakeholders, as we host regional and international Chiefs of Naval Staff to address the principal issues facing maritime security on the continent. This biennial event consists of in-depth panel discussions, breakout sessions and VIP exhibition tours to further highlight the occasion as the premier strategic gathering of Africa’s Navies, Coast Guards, Port and Coastal Authorities, Marine Police and related Ministries. Why Ghana? Perfectly situated as a significant hub on the Gulf of Guinea, Ghana is the proud host of this year’s IMDEC. Excitingly, 2019 marks the country’s 60th year of naval excellence. Hosted as part of the 60th Anniversary celebrations, IMDEC will showcase exclusive milestones of Ghana Navy’s achievements as well as forecast its future accomplishments within the maritime sector. VIP Speakers include: Ghana Navy Technical Committee • Commodore Issah Adam Yakubu Vice Admiral Ibok Ete Ibas Admiral James Foggo Chief of Naval Staff Commander, 6th Fleet Chief Staff Officer Nigeria Navy U.S. -

Simon Baynham, 'Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes? the Case of Nkrumah's National Security Service'

The Journal of Modern African Studies, 23, 1 (1985), pp. 87-103 Quis Custodiet Ipsos CustodesP: the Case of Nkrumah's National Security Service by SIMON BAYNHAM* FROM the ancient Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta to twentieth- century Bolivia and Zaire, from theories of development and under- development to models of civil-military relations, one is struck by the enormous literature on armed intervention in the domestic political arena. In recent years, a veritable rash of material on the subject of military politics has appeared - as much from newspaper correspondents reporting pre-dawn coups from third-world capitals as from the more rarefied towers of academe. Yet looking at the subject from the perspective of how regimes mobilise resources and mechanisms to protect themselves from their own security forces, one is struck by the paucity of empirically-based evidence on the subject.1 Since 1945, more than three-quarters of Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East have experienced varying levels of intervention from their military forces. Some states such as Thailand, Syria, and Argentina have been repeatedly prone to such action. And in Africa approximately half of the continent's 50 states are presently ruled, in one form or another, by the military. Most of the coups d'etat from the men in uniform are against civilian regimes, but an increasing proportion are staged from within the military, by one set of khaki-clad soldiers against another.2 The maintenance of internal law and order, and the necessary provision for protection against external threats, are the primary tasks of any political grouping, be it a primitive people surrounded by hostile * Lecturer in Political Studies, University of Cape Town, and formerly Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political and Social Studies, Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. -

French Navy Ship « Commandant L'herminier

**************** PRESS RELEASE **************** FRENCH NAVY SHIP « COMMANDANT L’HERMINIER » VISITS GHANA from June 4 to 7, 2012 French Navy Ship “Commandant L’Herminier” port call is scheduled on Monday June 4, 2012 at Tema Harbour. It will cast off on Thursday June 7, 2012. The purpose of the visit is to reinforce the existing ties between the French and the Ghanaian naval forces. Under command of Lieutenant Commander Gwenegan LE BOURHIS since December, 2010, the frigate “Commandant L’Herminier” has a staff of 9 officers, 51 petty officers and 40 boatmen and sailors. The French Navy Ship’s original tasking is anti-submarine warfare in coastal waters. “Commandant L’Herminier” is now going to take part with the Ghana Navy in common training activities, including a possible exercise at sea. Within the framework of its visit and as part of its cooperation with the civil society, the military navy’ staff is going to conduct operations of renovation to the benefit of the NGO Orphan Aid at Dodowa. Contact: Gwenola ROBLIN Press attaché 0302 21 45 93 Cell: 0208 86 92 43 [email protected] Ambassade de France au Ghana, 12th Road, off Liberation, Accra Tel +233.(0)21.21.45.50 / Fax +233.(0)21.21.45.89 www.ambafrance-gh.org / [email protected] PROGRAM Monday, 4 th June 2012, 9am : Cdt L’Herminier arrives at Tema Harbour Tuesday, 5 th of June, 10.30am : CO Cdt L’Herminier calls on Tema Chief and on Metropolitan Chief Executive. Wednesday, 6 th June 2012, 9am-4pm : Combined trainings at Tema Harbour (Participation to a safety exercise onboard, fire fighting exercise, immediate intervention, intervention procedures adapted to foreign vessel, flood fighting exercise onboard with and without assistance …) Very important notice : Journalists interested have to let me know by sending an e-mail to [email protected] or giving a call to 0208869243. -

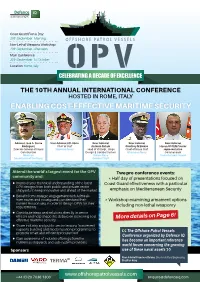

Enabling Cost-Effective Maritime Security

Coast Guard Focus Day: 29th September - Morning Non-Lethal Weapons Workshop: 29th September - Afternoon Main Conference: 30th September -1st October Location: Rome, Italy CELEBRATING A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE THE 10TH Annual International CONFERENCE HOSTED IN ROME, ITALY ENABLING COST-EFFECTIVE MARITIME SECURITY Admiral José A. Sierra Vice Admiral UO Jibrin Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rear Admiral Rodríguez Chief of Staff Antonio Natale Geoffrey M Biekro Hasan ÜSTEM/Senior Director General of Naval Nigerian Navy Head of VII Dept., Ships Chief of Naval Staff representative Construction Design & Combat System Ghanaian Navy Commandant Mexican Italian Navy Turkish Coast Guard Secretariat of the Navy General Staff Attend the world’s largest event for the OPV Two pre-conference events: community and: * Half day of presentations focused on • Improve your technical understanding of the latest Coast Guard effectiveness with a particular OPV designs from both public and private sector shipyards to keep innovative and ahead of the market emphasis on Mediterranean Security • Benefit from strategic engagement with Admirals from navies and coastguards; understand their * Workshop examining armament options current mission sets in order to design OPVs for their requirements including non-lethal weaponry • Contribute ideas and solutions directly to senior officers and help shape the debate on delivering cost- More details on Page 6! effective maritime security. • Share industry and public sector lessons from recent capacity building and modernisation programmes -

Biosecurity Measures to Reduce Influenza Infections In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Agbenohevi et al. BMC Research Notes (2015) 8:14 DOI 10.1186/s13104-014-0956-0 SHORT REPORT Open Access Biosecurity measures to reduce influenza infections in military barracks in Ghana Prince Godfred Agbenohevi1, John Kofi Odoom2*, Samuel Bel-Nono1, Edward Owusu Nyarko1, Mahama Alhassan1, David Rodgers1, Fenteng Danso3, Richard D Suu-Ire4, Joseph Humphrey Kofi Bonney2, James Aboagye2, Karl C Kronmann2,5, Chris Duplessis2,5, Buhari Anthony Oyofo5 and William Kwabena Ampofo2 Abstract Background: Military barracks in Ghana have backyard poultry populations but the methods used here involve low biosecurity measures and high risk zoonosis such as avian influenza A viruses or Newcastle disease. We assessed biosecurity measures intended to minimize the risk of influenza virus infection among troops and poultry keepers in military barracks. Findings: We educated troops and used a questionnaire to collect information on animal populations and handling practices from 168 individuals within 203 households in military barracks. Cloacal and tracheal samples were taken from 892 healthy domestic and domesticated wild birds, 91 sick birds and 6 water samples for analysis using molecular techniques for the detection of influenza A virus. Of the 1090 participants educated and 168 that responded to a questionnaire, 818 (75%) and 129 (76.8%) respectively have heard of pandemic avian influenza and the risks associated with its infection. Even though no evidence of the presence of avian influenza infection was found in the 985 birds sampled, only 19.5% of responders indicated they disinfect their coops regularly and 28% wash their hands after handling their birds. -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels. -

Defence Forces Review 2018 Defence Forces Review 2018

Defence Forces Review 2018 Defence Forces Review 2018 ISSN 1649-7066 Published for the Military Authorities by the Public Relations Section at the Chief of Staff’s Branch, and printed at the Defence Forces Printing Press, Infirmary Road, Dublin 7. Amended and reissued - 29/01/2019 © Copyright in accordance with Section 56 of the Copyright Act, 1963, Section 7 of the University of Limerick Act, 1989 and Section 6 of the Dublin University Act, 1989. 1 PEACEKEEPING AND PEACE MAKING INTERVENTIONS Launch of the Defence Forces Review In conjunction with an Academic Seminar National University of Ireland, Galway 22nd November 2018 Defence Forces Review 2018 RÉAMHRÁ Is pribhléid dom, mar Oifigeach i bhfeighil ar Bhrainse Caidreamh Poiblí Óglaigh na hÉireann, a bheith páirteach i bhfoilsiú 'Athbhreithniú Óglaigh na hÉireann 2018’ . Mar ab ionann le foilseacháin sna blianta roimhe seo, féachtar san eagrán seo ábhar a chur ar fáil a bheidh ina acmhainn acadúil agus ina fhoinse plé i measc lucht léite 'Athbhreithniú'. Is téama cuí agus tráthúil an téama atá roghnaithe don eagrán seo - Coimeád na Síochána agus Idirghabhálacha d'fhonn Síocháin a dhéanamh,, mar go dtugtar aitheantas ann do chomóradh 60 bliain ó thug Óglaigh na hÉireann faoi oibríochtaí coimeádta síochána na Náisiún Aontaithe ar dtús chomh maith le comóradh 40 bliain ó imscaradh Óglaigh na hÉireann go UNIFIL den chéad uair. Ba mhaith liom aitheantas a thabhairt don Cheannfort Rory Finegan as an obair mhór a chuir sé isteach agus as a thiomantas chun foilseachán na bliana a chur ar fáil. Tugtar aitheantas freisin don obair thábhachtach agus chóir a rinne comheagarthóirí ‘Athbhreithniú’ . -

Ghana-222S Regional Security Policy-Costs, Benefits and Consi-205

Ghana’s Regional Security Policy: Costs, Benefits and Consistency By Emma Birikorang 1 KAIPTC Paper No. 20, September 2007 1 Emma Birikorang is Programme Coordinator at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, Accra, Ghana. Introduction Since the early 1990s, Ghana’s contribution to maintaining sub-regional peace and security through its participation in peacekeeping and peacemaking has increased considerably. 2 Ghana’s involvement in resolving African and international conflicts can be traced to its intervention in the Congo crisis in the 1960s. Since then, the country has participated in several peacekeeping and peacemaking missions in countries like Lebanon, Kosovo, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sierra Leone, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. In all these missions, Ghana’s peacekeepers have played a significant role in alleviating immediate human suffering, and its mediators have helped in creating the basis for the resolution of conflicts in Africa such as in Liberia and Sierra Leone. By committing human and financial resources to these missions, the country’s international image has been enhanced. As a member state of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU), Ghana is committed to the various decisions, resolutions and protocols that guide these regional mechanisms with specific reference to peacekeeping. 3 The country is thus obligated to participate actively in decisions and activities of these organisations. Following the initial intervention in Congo in 1960, Ghana has been involved in more complex peacekeeping operations beginning with the Liberian and Sierra Leonean conflicts in the early 1990s. In Liberia, Ghana was among the five leading member states of ECOWAS which deployed troops before the UN Security Council belatedly sanctioned it.