Prostituting the Mutiny William R. Pinch, 26 June 2007 Draft: Not for Circulation Or Quotation Without Permission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Status of Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis

Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences 2 (5): 261 – 263 http://dx.doi.org/10.14737/journal.aavs/2014/2.5.261.263 Research Article Status of Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis Infection in an Indian Goshala Housing Poorly or Unproductive Cows Suffering with Clinical Bovine Johne’s Disease Tarun Kumar1, Ran Vir Singh1, Deepak Sharma1, Saurabh Gupta2, Kundan Kumar Chaubey2, Krishan Dutta Rawat2, Naveen Kumar2, Kuldeep Dhama3, Ruchi Tiwari4, Shoor Vir Singh2* 1Division of Genetics and Breeding, Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Izatnagar, Bareilly–243122, Uttar Pradesh, India; 2Microbiology Laboratory, Animal Health Division, Central Institute for Research on Goats (CIRG), Makhdoom, PO–Farah, Mathura– 281122, Uttar Pradesh, India; 3Division of Pathology, Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Izatnagar, Bareilly–243122, Uttar Pradesh, India; 4Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Immunology, College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, DUVASU, Mathura –281001, Uttar Pradesh, India *Corresponding author: [email protected]; [email protected] ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received: 2014–03–21 In the present study status of Mycobacterium avium (MAP) subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) Revised: 2014–04–25 was estimated in cows belonging to a Goshala located at the Holy town of Barsana in Accepted: 2014–04–26 Mathura district, wherein cows were suffering with clinical Bovine Johne’s Disease (BJD). Randomly 118 cows were sampled and screened for MAP. Of 118 fecal samples screened by microscopy and culture, 45 (38.1%) and 10 (8.4%) were positive for MAP infection, Key Words: Bovine Johne’s respectively. While screening of 118 serum samples by ‘Indigenous ELISA kit’, 32 (27.1%) disease, Microscopy, ELISA, were positive. -

State: UTTAR PRADESH Agriculture Contingency Plan for District

State: UTTAR PRADESH Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: MATHURA 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/ Ecological Zone Agro-Ecological Sub Region(ICAR) Western Plain Zone, Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Commission) Upper Gangetic Plain Region Agro-Climatic Zone (NARP) UP-3 South-western Semi-arid Zone List all the districts falling the NARP Zone* (^ 50% area falling Firozabad, Aligrah, Hathras, Mathura, Mainpuri, Etah in the zone) Geographical coordinates of district headquarters Latitude Longitude Altitude (mt) 27.30 N 77.40 E Name and address of the concerned - ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRS/RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district with address Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Dairy Farm, Veterinary College, Mathura Name and address of the nearest Agromet Field C.S. Azad University of Agriculture & Technology Kanpur Unit(AMFU,IMD)for agro advisories in the Zone 1.2 Rainfall Normal RF Normal Rainy Normal Onset Normal Cessation (mm) Days (Number) (Specify week and month) (Specify week and month) SW monsoon (June-sep) 518.7 45 3rdweek of June 4thd week of September Post monsoon (Oct-Dec) 25.3 10 Winter (Jan-March) 33.7 10 - - Pre monsoon (Apr-May) 13.7 2 - - Annual 591.4 67 - - 1.3 Land use pattern Geographical Cultivable Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other of the district area (ha) area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows (Latest (ha) (ha) agricultural (ha) Misc.tree land (Ha) (ha) statistics) use (ha) crops and groves Area in (000’ 330.3 284.5 1.6 39.6 1.3 4.9 0.9 3.2 5.5 4.0 ha) 1.4 Major Soils Area(‘000 ha) Percent(%) of total Deep Fine soil 82.6 25% Deep fine moderate with loamy soil 66.1 20% Deep loamy soil 59.5 18% Other(Eroded) 122.2 37% 1.5 Agricultural land use Area(‘000 ha) Cropping intensity (%) Net sown area 269.3 140 % Area sown more than once 129.1 Gross cropped area 398.4 1.6 Irrigation Area(‘000 ha) Net irrigation area 269.165 Gross irrigated area 329.709 Rain fed area 0.164 Sources of irrigation(Gross Irr. -

Infected Areas As on 3 August 1972 — Zones Infectées Au 3 Août 1972

— 304 SMALLPOX (amuL) - VARIOLE (suite) c D C D Africa (conid.) — Afrique (suite) INDIA — INDE 23-29. YU PAKISTAN 18-24, VI W est P akistan C D Calcutta (P) (excl. A ). 4 6 SUDAN — SOUDAN 23-29.VH North-West Frontier Province 9-15. VII D istricts Bahr el Ghasal Province Andhra Pradesh State Wau Rur. C................. 2 ... Bannu .................... 6 1 Hyderabad D. 5 0 Dera Ismail Khan . 12 3 Kassala Province K o h a t .................... 1 0 Madhya Pradesh State Aroma Rur, C. 6 ... Peshawar ..... 9 0 17 6 Tikamgarh D ............... c D c D 25.VI-1.VH 2-8. VU Asia — Asie Maharashtra State Lahore (excl. A) . 28 1 3 0 c D C D Thana D ....................... 12 5 W est P akistan BANGLADESH 2-8.VU 9-15.VH Mysore State North-West Frontier Province Dacca Division 2 Bannu D ................... 0 1 0 1 Dacca D ................... 0 0 1 0 Bidar D ........................ 0 1 1 Peshawar D. 27 1 17 1 Faridpur D ............... 66 6 65 23 Gulbarga D.................. Punjab Province Khulna Division Uttar Pradesh State D istricts D istricts D istricts Gujranwala .... 24 3 1 0 Bakerganj (Barisal). 98 15 75 44 B ah raic h ............... ... 48 9 Muzaffargarh . 0 0 1 0 Jessore ................... 42 2 9 0 Ballia ....................... 0 1 Rahim Yar Khan. 1 0 5 1 Khulna ................ 36 3 43 11 Bareilly................... - 16 1 S ia lk o t.................... 0 0 6 0 Patuakhali .... 0 0 8 5 Kberi ....................... 12 1 11-17.VI1 Rajshahi Division M ain p u ri.................. -

Uttar Pradesh BSAP

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN, UTTAR PRADESH (U.P.) Coordinator Coordinated by: U. Dhar GBPIHED TEAM S.S. Samant Asha Tewari R.S. Rawal NBSAP, U.P. Members Dr. S.S. Samant Dr. B.S. Burphal DR. Ipe M. Ipe Dr. Arun Kumar Dr. A.K. Singh Dr. S.K. Srivastava Dr. A.K. Sharma Dr. K.N. Bhatt Dr. Jamal A. Khan Miss Pia Sethi Dr. Satthya Kumar Miss Reema Banerjee Dr. Gopa Pandey Dr. Bhartendu Prakash Dr. Bhanwari Lal Suman Dr. R.D. Dixit Mr. Sameer Sinha Prof. Ajay S. Rawat 1 Contributors B.S. Burphal Pia Sethi S.K. Srivastava K.N. Bhatt D.K. pande Jamal A. Khan A.K. Sharma 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 . Brief background of the SAP 1.2 . Scope of the SAP 1.3 . Objectives of the SAP 1.4 . Contents of the SAP 1.5 . Brief description of the SAP CHAPTER 2. PROFILE OF THE AREA 2.6 . Geographical profile 2.7 . Socio- economic profile 2.8 . Political profile 2.9 . Ecological profile 2.10.Brief history CHAPTER 3. CURRENT (KNOWN) RANGE AND STATUS OF BIODIVERSITY 3.1. State of natural ecosystems and plant / animal species 3.2. State of agricultural ecosystems and domesticated plant/ animal species CHAPTER 4. STATEMENTS OF THE PROBLEMS RELATED TO BIODIVERSITY 4.1. Proximate causes of the loss of biodiversity 4.2. Root causes of the loss of biodiversity CHAPTER 5. MAJOR ACTORS AND THEIR CURRENT ROLES RELEVANT TO BIODIVERSITY 5.1. Governmental 5.2. Citizens’ groups and NGOs 5.3. Local communities, rural and urban 5.4. -

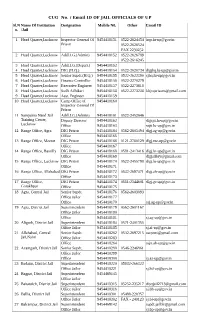

CUG No. / Email ID of JAIL OFFICIALS of up Sl.N Name of Institution Designation Mobile N0

CUG No. / Email ID OF JAIL OFFICIALS OF UP Sl.N Name Of Institution Designation Mobile N0. Other Email ID o. /Jail 1 Head Quarter,Lucknow Inspector General Of 9454418151 0522-2624454 [email protected] Prison 0522-2626524 FAX 2230252 2 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418152 0522-2626789 0522-2616245 3 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Depart.) 9454418153 4 Head Quarter,Lucknow DIG (H.Q.) 9454418154 0522-2620734 [email protected] 5 Head Quarter,Lucknow Senior Supdt.(H.Q.) 9454418155 0522-2622390 [email protected] 6 Head Quarter,Lucknow Finance Controller 9454418156 0522-2270279 7 Head Quarter,Lucknow Executive Engineer 9454418157 0522-2273618 8 Head Quarter,Lucknow Sodh Adhikari 9454418158 0522-2273238 [email protected] 9 Head Quarter,Lucknow Asst. Engineer 9454418159 10 Head Quarter,Lucknow Camp Office of 9454418160 Inspector General Of Prison 11 Sampurna Nand Jail Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418161 0522-2452646 Training Center, Deputy Director 9454418162 [email protected] Lucknow Office 9454418163 [email protected] 12 Range Office, Agra DIG Prison 9454418164 0562-2605494 [email protected] Office 9454418165 13 Range Office, Meerut DIG Prison 9454418166 0121-2760129 [email protected] Office 9454418167 14 Range Office, Bareilly DIG Prison 9454418168 0581-2413416 [email protected] Office 9454418169 [email protected] 15 Range Office, Lucknow DIG Prison 9454418170 0522-2455798 [email protected] Office 9454418171 16 Range Office, Allahabad DIG Prison 9454418172 0532-2697471 [email protected] Office 9454418173 17 Range Office, DIG Prison 9454418174 0551-2344601 [email protected] Gorakhpur Office 9454418175 18 Agra, Central Jail Senior Supdt. -

Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana

Ministry of Urban Development Government of India Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana HRIDAY ân; 1 HRIDAY Guidelines Contents 13 HRIDAY Cities 14 Ajmer 16 Amrawati 18 Amritsar 20 Badami 22 Dwaraka 24 Gaya 26 Kanchipuram 28 Mathura 30 Puri 32 Varanasi 34 Vellankanni 36 Warrangal HRIDAY ân; Guidelines Need for the scheme India is endowed with rich and diverse natural, historic and cultural resources. However, it is yet to explore the full potential of such resources to its full advantages. Past efforts of conserving historic and cultural resources in Indian cities and towns have often been carried out in isolation from the needs and aspirations of the local communities as well as the main urban development issues, such as local economy, urban planning, livelihoods, service delivery, and infrastructure provision in the areas. The development of heritage cities is not about development and conservation of few monuments, but development of the entire city, its planning, its basic services, the quality of life to its communities, its economy and livelihoods, cleanliness, and security in sum, the reinvigoration of the soul of that city and the explicit manifestation of the its unique character. Since 2006, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India has initiated various capacity building initiatives with a focus on development of Indian Heritage cities. Conservation of urban heritage has been often carried out without linkages with the city urban planning processes/tools and local economy and service delivery aspects. Heritage areas are neglected, overcrowded with inadequate basic services and infrastructure, such as water supply, sanitation, roads, etc. Basic amenities like toilets, signages, street lights are missing. -

Two Months' Trip: Hyerabad, Saharanpur

RM 22 NOT FOR Ara, India PUt ICATION January 2, 1948 Mr. Walter S:. Rogers Institute of Current World Affairs 5e Fifth Avenue New York 18, N.Y. Dear Mr. Roers: This letter reports, in brief, my activities during the past two months It also partly explains my failure to write earlier. If it is more personal in tone than might ordinarily be expected, that fact reflects the nature of my experiences, and I hope you will once aain excuse the personal element. It was on NOvember 19th, in Po0na, that I wrote a rough first draft of my letter 21. On the foll owin day I left by train for the historic fort town of Gu!barga, now a district seat in southwestern Hyderabad tate . I stoped overnight there with Aslf and Qudsia Abroad, a youu Muslim couple whomX had met at Karachi through a Muslim Univer sity friend. Asif is on the staff of the Hyderabad State Bank, and was Just cmpletlng six months of training e &resistant manager of its Gul barga branch. Both he and Qudsla are residents of the capital, Hydera- bad itself, and although they were able to show me some aspects of life in Gulbara, both considered it very definitely a 'mofuseil' (country) town, and-were eaer to return to the more social and cosmopolitan capi- tal. In a large old mosque wthin the ancient fort walls, Asif showed me Gulbara's major immediate problem: some 3000 Muslims who had fled from the Central India Btates and Central Provinces to the Muslim-ruled state of Hyderabad, because they had felt insecure in a predominantly Hindu area. -

Basic Information of Urban Local Bodies – Uttar Pradesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF URBAN LOCAL BODIES – UTTAR PRADESH As per 2006 As per 2001 Census Election Name of S. Growth Municipality/ Area No. of No. Class House- Total Rate Sex No. of Corporation (Sq. Male Female SC ST (SC+ ST) Women Rate Rate hold Population (1991- Ratio Wards km.) Density Membe rs 2001) Literacy 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 I Saharanpur Division 1 Saharanpur District 1 Saharanpur (NPP) I 25.75 76430 455754 241508 214246 39491 13 39504 21.55 176 99 887 72.31 55 20 2 Deoband (NPP) II 7.90 12174 81641 45511 36130 3515 - 3515 23.31 10334 794 65.20 25 10 3 Gangoh (NPP) II 6.00 7149 53913 29785 24128 3157 - 3157 30.86 8986 810 47.47 25 9 4 Nakur (NPP) III 17.98 3084 20715 10865 9850 2866 - 2866 36.44 1152 907 64.89 25 9 5 Sarsawan (NPP) IV 19.04 2772 16801 9016 7785 2854 26 2880 35.67 882 863 74.91 25 10 6 Rampur Maniharan (NP) III 1.52 3444 24844 13258 11586 5280 - 5280 17.28 16563 874 63.49 15 5 7 Ambehta (NP) IV 1.00 1739 13130 6920 6210 1377 - 1377 27.51 13130 897 51.11 12 4 8 Titron (NP) IV 0.98 1392 10501 5618 4883 2202 - 2202 30.53 10715 869 54.55 11 4 9 Nanauta (NP) IV 4.00 2503 16972 8970 8002 965 - 965 30.62 4243 892 60.68 13 5 10 Behat (NP) IV 1.56 2425 17162 9190 7972 1656 - 1656 17.80 11001 867 60.51 13 5 11 Chilkana Sultanpur (NP) IV 0.37 2380 16115 8615 7500 2237 - 2237 27.42 43554 871 51.74 13 5 86.1 115492 727548 389256 338292 65600 39 65639 23.38 8451 869 67.69 232 28 2 Muzaffarnagar District 12 Muzaffarnagar (NPP) I 12.05 50133 316729 167397 149332 22217 41 22258 27.19 2533 892 72.29 45 16 13 Shamli -

ANSWERED ON:18.07.2014 DEMONSTRATION by WIDOWS Nath Shri Chand

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1219 ANSWERED ON:18.07.2014 DEMONSTRATION BY WIDOWS Nath Shri Chand Will the Minister of WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether the widows living in Varanasi and Vrindavan held demonstration in Delhi recently to protest against the disrespect, ill treatment and injustices reportedly being meted out to them; (b) if so, the details thereof, and the reasons therefor alongwith the demands of these widows; and (c) the action taken/proposed to be taken by the Government in this regard? Answer MINISTER OF WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT (SHRIMATI MANEKA SANJAY GANDHI) (a)& (b): Reports appeared in the Media that about 100 widows from Vrindavan and Varanasi gathered in the capital on 23rd June 2014 demanding the Government to take measures for welfare of widows who are living in Vrindavan and Varanasi and also to introduce and pass a Bill to protect their rights. (c):The Government is implementing two shelter based schemes for women in difficult circumstances to improve their living conditions. i. Swadhar Scheme: Swadhar Scheme was launched in the year 2001-2002 for rehabilitation of women in difficult circumstances. The scheme provides primary need of shelter, food, clothing and care to the marginalized women/girls living in difficult circumstances who are without any social support. The beneficiaries include widows deserted by their families and relatives left uncared near religious places where they are victims of exploitation, women prisoners released from jail and without family support, and similarly placed women in difficult circumstances. -

Areas Removed from the Infected Area List Between 13 and 19 November 1970 Territoires Supprimés De La Liste Des Territoires Infectés Entre Les 13 Et 19 Novembre 1970

— 527 — LOUSE-BORNE TYPHUS FEVER (contd.) c D c D LOUSE-BORNE RELAPSING FEVER TYPHUS À POUX (suite) ETHIOPIA (contd.) 19-25. VII 2 6 .v n - i.v m FIÈVRE RÉCURRENTE À POUX ÉTHIOPIE (suite) Africa — Afrique Africa (contd.) — Afrique (suite) Provinces (contd. -- suite) C D c D c D Tigre ................... 7 0 4 0 ETHIOPIA — ÉTHIOPIE 19-25.VII 26.VII-1.VIII BURUNDI (contd. — suite) 27.IX-3.X Woliega ............... 7 0 0 0 Addis Ababa (A) . 46 0 17 0 W o l l o ................... 2 0 0 0 Bururi, Province . 51 2 P rovinces 2-8.VHI 9-15. VIH A rusi........................... 2 0 4 0 Kitega, Province . 248 1 0 Addis Ababa (A) . 0 0 6 Begem dir................... 9 0 3 0 Muhinga, Province . 1 0 Gamu-Gofa .... 1 0 2 0 Provinces G o ja m ....................... 6 0 2 0 Muramvya, Province A rusi....................... 7 0 2 0 I lu b a b o r................... 5 0 0 0 B a i e ....................... 15 0 1 0 0 0 0 M w aro , Arr................. 12 0 K affa........................... 2 Begemdir ...... 12 0 7 0 Shoa (excl. Eritrea (excl. Asmara 0 Ngozi, Province . 1 338 29 Addis Ababa (A)) . 6 0 12 (A), Assab (PA) & Tigre ............................... 4 0 0 0 Massawa (P)) . 13 0 0 0 W o lie g a .......................... 59 0 0 0 c D C D G o ja m ................... 20 0 54 0 W o l l o ............................... 10 0 0 0 ETHIOPIA — ÉTHIOPIE 19-25.VII 26.VU-1.VUI Ilu b a b o r.............. -

Territoires Supprimés De La Liste Des Territoires Infectés Entre Les 27 Mai Et 3 Juin 1965 Areas Removed from the Infected Area List Between 27 May and 3 June 1965

— 276 — Punjab, State Sultanpur, District . ■ 15.XI.60 Lahore, Division ÉTHIOPIE — ETHIOPIA ■ 17.IX.60 ^ Amritsar, District . B 24.IV Tehri Garhwal, District . ■ 30.1 Sheikhupura, District . A 15.V (excl. Addis ABaBa & Asmara) Bhatinda, District . ■ 30.IV Uharkashi, District . ■ 27.111 Gurdaspur, District . ■ 3.II.64 Unnao, District .... ■ 15.V.59 Peshawar, Division Addis ABaBa (A) .... A 8.V 1 Hissar, D istrict............... ■ 28.X1I.64 Hazara, District .... B l.V Ludhiana, District . ■ 22.IV West Bengal, State RÉPUBLIQUE ARABE UNIE. Mohindergarh, District . ■ 16.11 Bankura, District .... ■ 23.1 Rawalpindi, Division Patiala, District .... ■ 15.1 BirbBum, District. ■ 26.XII.64 UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC Rohtak, District .... ■ 9.IV ♦ Burdwan, District . ■ 15.V Gujrat, District............... B 13.HI Darjeeling, District . ■ 2.II Rawalpindi, District Beheira, Governorate . B 13,11 Rajasthan, State Hooghly, District .... ■ 26.1 (excl. Rawalpindi (A)) . B 20.III Ajmer, D istrict........ B 6.IU Howrah, District .... ■ 20.1.56 Rawalpindi, Cantonment. B 13.HI Alwar, District .... ■ 19.XI1.64 Jalpaiguri, District . « 12.1V Amérique — America Banswara, District . ■ 13.HI Malda, District.................. ■ 16.1 Sargodha, Division Bhilwara, District . ■ 19.XII.64 Midnapur, District . ■ 23.XII.62 Jhang, D istrict............... B 27.HI Bikaner, District .... ■ 21.XI.64 MurshidaBad, District. ■ 23.XII.58 Jhang, D. : BOLIVIE — BOLIVIA . B 19.XII.64 Churu, District............... ■ 21.XI.64 24-Parganas, District . ■ 28.X.62 Jhang Maghiana . B 20.III Dungarpur, District. ■ 12.XII.64 West Dinajpur, District . ■ 20.II1 Lyallpur, District .... B 20.III Ganganagar, District . » 19.XII.64 ÉQUATEUR — ECUADOR Jaipur, District............... «1.1 INDONÉSIE — INDONESIA Jhalawar, District. ■ 3.IV YEMEN Canar, Province Nagaur, District ...