Weir, Johnny (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorabilia List As of 6-17-10

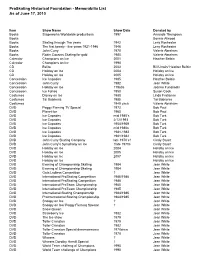

ProSkating Historical Foundation - Memorabilia List As of June 17, 2010 Item Show Name Show Date Donated by Books Stageworks Worldwide productions 1997 Amanda Thompson Books Bonnie Atwood Books Skating through The years 1942 Leny Rochester Books The first twenty - five years 1921-1946 1946 Leny Rochester Books John Curry 1978 Valerie Abraham Books Robin Cousins Skating for gold 1980 Valerie Abraham Calendar Champions on Ice 2001 Heather Belbin Calendar Champions on Ice 1998 CD Belita 2003 Bill Unwin/ Heather Belbin CD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice CD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice Concession Ice Capades 1985 Heather Belbin Concession John Curry 1982 Jean White Concession Holiday on Ice ?1960s Joanne Funakoshi Concession Ice Follies 1950 Susan Cook Costumes Disney on Ice 1980 Linda Fratianne Costumes Tai Babilonia 1985 Tai Babilonia Costumes 1949 circa Valerie Abraham DVD Peggy Fleming TV Special 1972 Bob Paul DVD Planet Ice 1960 Bob Paul DVD Ice Capades mid 1980’s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 2/12/1993 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1958/1959 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades mid 1980s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981-1982 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981/1982 Bob Turk DVD John Curry Skating Company late 1970’s? Cindy Stuart DVD John Curry’s Symphony on Ice ?late 1970s Cindy Stuart DVD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2007 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice Holiday on Ice DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Gala Ladiess Competition -

America's Stars on Ice Shine for Groups in 2019!

America’s Stars on Ice Shine for Groups in 2019! See the best of American figure skating past, present and future in the all-new Stars on Ice presented by Musselman’s tour. Olympic Medalists NATHAN CHEN*, MAIA & ALEX SHIBUTANI, ASHLEY WAGNER, JASON BROWN*, MIRAI NAGASU, JEREMY ABBOTT and BRADIE TENNELL will join Olympic Gold Medalists MERYL DAVIS & CHARLIE WHITE, plus World Medalists MADISON HUBBELL & ZACH DONOHUE and U.S Medalist VINCENT ZHOU in this true red, white and blue celebration on ice! Showcased at each performance are thrilling solo numbers, along with show-stopping ensemble pieces — a Stars on Ice signature! Gather your group and enjoy a night to remember. Larger groups may qualify to receive additional autographed items and experiences that are exclusive to Stars on Ice. *Not appearing in all cities. 2019 GROUP SALES – SPECIAL OFFERS 10+ TICKETS Exclusive $10 discount per ticket (excludes on ice seats). 20-49 TICKETS Discount plus 2 free tickets and 1 cast-signed poster. 50-99 TICKETS Discount plus 4 free tickets, admission to pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring 2 cast members, and 3 cast-signed posters. 100+ TICKETS Discount plus 6 free tickets, admission to pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring 2 cast members, “Welcome” announcement before the show, 3 cast-signed posters, autographed Stars on Ice card for each member of the group, and a skater visit. starsonice.com DATE AND CAST SUBJECT TO CHANGE. STARS ON ICE AND LOGO ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISING COMPANY, LLC. © 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. -

![Eliza Gilmore]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5808/eliza-gilmore-605808.webp)

Eliza Gilmore]

3/27/1852 From:Charles H. Howard To: Mother [Eliza Gilmore] CHH-001 Kent's Hill, Maine Kent's Hill, March, 27, 1852. [This is Charles' first letter away from home. He was 13, born Aug 28, 1838] Dear Mother, I now sit down to tell you how I get along away from all of my friends, for I believe that I have never been away before except that some one of my brothers has been with me but I don't know but what I get along as well so far as though some one of my friends had been with me. I am situated in a pleasant room with a pleasant room-mate. I was lucky enough to get in with Mr. Hewet whom I was acquainted with before this I suppose Rowland informed you of. Anyone would hardly think but that if I am pleasantly situated I might be happy. But although I said I did not know but I prospered as well so far without my brothers with me, yet I do not feel so well, I feel sometimes home sick but not much. But this is nothing, I can't expect to be at home with my mother always, tho I should like to be. My health is the main thing for sure. It is as good as when I left home I think. I like Mr. Torsey [Henry P. Torsey, Headmaster of Kent's Hill School] well as a teacher. I have not spoken with him since I saw him with Rowland at the Mansion. -

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement*

Homosexuality and the Olympic Movement* By Matthew Baniak and Ian Jobling Sport remains “one of the last bastions of cultural and the inception of the modern Games until today. An Matthew Baniak institutional homophobia” in Western societies, despite examination of key historical events that shaped the was an Exchange Student from the University of Saskatchewan, the advances made since the birth of the gay rights gay rights movement helps determine the effect homo- Canada at the University of movement.1 In a heteronormative culture such as sport, sexuality has had on the Olympic Movement. Through Queensland, Australia in 2013. Email address: mob802@mail. lack of knowledge and understanding has led to homo- such scrutiny, one may see that the Movement has usask.ca phobia and discrimination against openly gay athletes. changed since the inaugural modern Olympic Games The Olympic Games are no exception to this stigma. The in 1896. With the momentum of news surrounding the Ian Jobling goal of the Olympic Movement is to 2014 Sochi Games and the anti-gay laws in Russia, this is Director, Centre of Olympic … contribute to building a peaceful and better world issue of homosexuality and the Olympic Movement Studies and Honorary Associate by educating youth through sport united with art has never been so significant. Sections of this article Professor, School of Human Movement Studies, University of and culture practiced without discrimination of any will outline the effect homosexuality has had on the Queensland. Email address: kind and in the -

8 August 2000

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY FOURTIETH SESSION 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 1 © 2001 International Olympic Committee Published and edited jointly by the International Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Academy 2 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 40TH SESSION FOR YOUNG PARTICIPANTS SPECIAL SUBJECT: OLYMPIC GAMES: ATHLETES AND SPECTATORS 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 ANCIENT OLYMPIA 3 EPHORIA (BOARD OF DIRECTORS) OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY President Nikos FILARETOS IOC Member Honorary life President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH IOC President 1st Vice-president George MOISSIDIS Member of the Hellenic Olympic Committee 2nd Vice-president Spiros ZANNIAS Honorary Vice-president Nikolaos YALOURIS Member ex-officio Lambis NIKOLAOU IOC Member President of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Members Dimitris DIATHESSOPOULOS Secretary General of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Georgios YEROLIMBOS Ioannis THEODORAKOPOULOS President of the Greek Association of Sports Journalists Epaminondas KIRIAZIS Cultural Consultant Panagiotis GRAVALOS 4 IOC COMMISSION FOR CULTURE AND OLYMPIC EDUCATION President Zhenliang HE IOC member in China Vice-president Nikos FILARETOS IOC member in Greece Members Fernando Ferreira Lima BELLO IOC member in Portugal Valeriy BORZOV IOC member in Ukraine Ivan DIBOS IOC member in Peru Sinan ERDEM IOC member in Turkey Nat INDRAPANA IOC member in Thailand Carol Anne LETHEREN t IOC member in Canada Francis NYANGWESO IOC member in Uganda Lambis W. NIKOLAOU IOC member in Greece Mounir SABET IOC member in -

The Skating Lesson Interview with Rudy Galindo

The Skating Lesson Podcast Transcript The Skating Lesson Interview with Rudy Galindo Jenny Kirk: Hello, and welcome to The Skating Lesson podcast where we interview influential people from the world of figure skating so they can share with us the lessons they learned along the way. I’m Jennifer Kirk, a former US ladies competitor and a three-time world team member. Dave Lease: I’m David Lease. I was never on the world team, I’m a far cry from the pewter medal, but I am a figure skating blogger and a current adult skater. Jenny: This week, we had a few technical issues that we’re so sorry about… Dave: We had BOOT PROBLEMS!! Jenny: Boot problems, Tai Babilonia would have told us! We had some technical issues, so we can only give you guys the audio portion of our interview with our guest this week, Rudy Galindo. But thank you for hanging with us, and we’re gonna try to come back next week with a stronger interview where you can actually see our guest in addition to hearing him. Or her. Dave: Well, this week, we are absolutely thrilled to welcome Rudy Galindo to the show. Rudy Galindo is best known for being the 1996 US national champion. He was a pro skater for many years and about every competition known to man. He was on Champions on Ice for well over a decade. And he was also a two-time US national champion in pairs with Kristi Yamaguchi. Jenny: And it should be noted – Dave and I did a lot of research prior to this interview. -

Las Vegas, Nevada

2021 Toyota U.S. Figure Skating Championships January 11-21, 2021 Las Vegas | The Orleans Arena Media Information and Story Ideas The U.S. Figure Skating Championships, held annually since 1914, is the nation’s most prestigious figure skating event. The competition crowns U.S. champions in ladies, men’s, pairs and ice dance at the senior and junior levels. The 2021 U.S. Championships will serve as the final qualifying event prior to selecting and announcing the U.S. World Figure Skating Team that will represent Team USA at the ISU World Figure Skating Championships in Stockholm. The marquee event was relocated from San Jose, California, to Las Vegas late in the fall due to COVID-19 considerations. San Jose meanwhile was awarded the 2023 Toyota U.S. Championships, marking the fourth time that the city will host the event. Competition and practice for the junior and Championship competitions will be held at The Orleans Arena in Las Vegas. The event will take place in a bubble format with no spectators. Las Vegas, Nevada This is the first time the U.S. Championships will be held in Las Vegas. The entertainment capital of the world most recently hosted 2020 Guaranteed Rate Skate America and 2019 Skate America presented by American Cruise Lines. The Orleans Arena The Orleans Arena is one of the nation’s leading mid-size arenas. It is located at The Orleans Hotel and Casino and is operated by Coast Casinos, a subsidiary of Boyd Gaming Corporation. The arena is the home to the Vegas Rollers of World Team Tennis since 2019, and plays host to concerts, sporting events and NCAA Tournaments. -

Sunday, May 6 • 4 Pm

This year’s Stars on Ice tour will put American fans front and center to experience the best of the U.S. Figure Skating team that will compete in Pyeongchang, South Korea. The tour will feature U.S. National Champion Nathan Chen and Olympic medal hopefuls including; three-time National Champion and 2016 World Silver Medalist Ashley Wagner, two-time Ice Dance National Champions and three-time World medalists Maia & Alex Shibutani, 2017 U.S. Ladies Champion Karen Chen, as well as National Champion, and huge crowd favorite, Jason Brown. The Emmy Award- winning production will also feature U.S. Olympic royalty, Ice Dance Gold Medalists Meryl Davis & Charlie White. SUNDAY, MAY 6 • 4 PM REGULAR PRICE YOUR PRICE SPECIAL INCENTIVES FOR LARGE GROUPS $88.00 $78.00 Sections 103, 104, 116, 117 (20-49 Tickets) Discount plus 2 free tickets and one cast-signed poster. $83.00 $73.00 Sections 102, 105, 115, 118, (50-99 Tickets) Discount plus (4) free tickets, admission to C5-C7, C25-C27 pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring $48.00 $38.00 Sections 101, 106, 114, 119 2 cast members, and (3) cast-signed posters. & Rows 1-12 in 107-113, (100+ Tickets) Discount plus (6) free tickets, admission to 120-126 pre-show warm-ups and our popular Icebreaker session featuring 2 cast members, “Welcome” announcement before $28.00 $28.00 Sections 107-113, 120-126 the show, (3) cast-signed posters, autographed Stars on Ice card for (No Discount) (Rows 13+) each member of the group, and a skater visit. -

Adream Season

EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA MOVES TO CANADIAN COACH ALJONA SAVCHENKO KAETLYN BRUNO OSMOND MASSOT TURN TO A DREAM COACHING SEASON MADISON CHOCK & SANDRA EVAN BATES GO NORTH BEZIC OF THE REFLECTS BORDER ON HER CREATIVE CAREER Happy family: Maxim Trankov and Tatiana Volosozhar posed for a series of family photos with their 1-year-old daughter, Angelica. Photo: Courtesy Sergey Bermeniev Adam Rippon and his partner Jena Johnson hoisted their Mirrorball Trophies after winning “Dancing with the Stars: Athlete’s Edition” in May. Photo: Courtesy Rogers Media/CityTV Contents 24 Features VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 4 | AUGUST 2018 EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA 6 Feeling Confident and Free MADISON CHOCK 10 & EVAN BATES Olympic Redemption A CREATIVE MIND 14 Canadian Choreographer Sandra Bezic Reflects on Her Illustrious Career DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS 22 Aljona Savchenko and Bruno Massot Turn to Coaching ON THE KAETLYN OSMOND COVER Ê 24 Celebrates a Dream Season OLYMPIC INDUCTIONS 34 Champions of the Past Headed to Hall of Fame EVOLVING ICE DANCE HUBS 38 Montréal Now the Hot Spot in the Ice Dance World THE JUNIOR CONNECTION 40 Ted Barton on the Growth and Evolution of the Junior Grand Prix Series Kaetlyn Osmond Departments 4 FROM THE EDITOR 44 FASHION SCORE All About the Men 30 INNER LOOP Around the Globe 46 TRANSITIONS Retirements and 42 RISING STARS Coaching Changes NetGen Ready to Make a Splash 48 QUICKSTEPS COVER PHOTO: SUSAN D. RUSSELL 2 IFSMAGAZINE.COM AUGUST 2018 Gabriella Papadakis drew the starting orders for the seeded men at the French Open tennis tournament, and had the opportunity to meet one of her idols, Rafael Nadal. -

Figure Skating's Greatest Stars Epub Downloads a Beautifully Illustrated Celebration of the Best Athletes from This Wildly Popular Sport

Figure Skating's Greatest Stars Epub Downloads A beautifully illustrated celebration of the best athletes from this wildly popular sport. Figure Skating's Greatest Stars profiles 60 great skaters, including champions in men's, women's, pairs and ice dancing. Informative essays describe their careers and championship moments, as well as the definitive events that have made figure skating one of the leading spectator sports in North America. Fans of all ages will delight in reading the stories of these stars who have jumped higher, spun tighter and skated more gracefully as they pushed skating's artistic and technical boundaries. Some of the 60 athletes featured are: Dick Button (late 1940s and early 1950s), United States Liudmila and Oleg Protopopov (1960s), Soviet Union Brian Boitano (1980s), United States Elvis Stojko (1990s), Canada Oksana Grishuk and Evgeny Platov (1990s), Russia Jamie Sale and David Pelletier (late 1990s and 2000s), Canada Brian Joubert (2000s), France Qing Pang and Jian Tong (2000s), China Tanith Belbin and Ben Agosto (2000s), United States Michelle Kwan (2000s), United States. Figure Skating's Greatest Stars is the perfect fanbook for the millions who love this sport. Hardcover: 196 pages Publisher: Firefly Books (September 25, 2009) Language: English ISBN-10: 1554073243 ISBN-13: 978-1554073245 Product Dimensions: 9 x 0.8 x 11 inches Shipping Weight: 3 pounds (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.3 out of 5 stars 5 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #832,575 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #34 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Winter Sports > Ice Skating & Figure Skating Enjoyable to browse or read cover-to-cover. -

Performer & Production Staff Bios

RAND PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS US WINTER TOUR 2014 Performer & Production Staff Bios Michael Chack – Male Soloist & Associate Choreographer US National Bronze Medalist US National & International Team Member Michael, from New York, NY, started skating at the age of 5. When he was only 11years old he moved away from home to begin training with World & Olympic Coach, Peter Burrows. His first trip to US National Championships was at the age of 15, and by 1991 was part of the National Team in the Senior Division (when he earned a 5th-place finish at US Championships). At the Skate America International Competition later that year he landed his first triple axel in competition, and in 1993 Michael was standing on the podium when he captured the country’s bronze medal! For the next two seasons Michael was a US World Team. Over Michael’s competitive career he won numerous qualifying and international competitions including: the World University Games, the US Olympic Festival, the Norway International (twice), the Tropee De France, and the Nebelhorn Trophy (Germany). As a professional Michael has been a lead principal performer for Holiday on Ice, Broadway on Ice (National Tour), Disney on Ice (World Tour), Snoopy’s Endless Summer, and Celebration on Ice and Spellbound on Ice (Hong Kong). Michael originated the male soloist role in The Holiday Ice Spectacular 2008 and is thrilled to be rejoining the show for the 5th tour in 2014! Notably, Michael is the associate choreographer and performance director of the show in 2014. Kristin Cowan & Sean Wirtz – Adagio Team Kristin – International Professional Skater for world-leading shows Sean – Canadian National Champion & International Team Member Kristin began skating at the age of five in her hometown of Spokane, Washington. -

Yuzuru HANYU Place of Birth: Sendai Height: 171 Cm JPN Home Town: Sendai Profession: University Student Hobbies: Music Start Sk

MEN Date of birth: 07.12.1994 Yuzuru HANYU Place of birth: Sendai Height: 171 cm JPN Home town: Sendai Profession: university student Hobbies: music Start sk. / Club: 1998 / ANA Minato Tokyo Coach: Brian Orser, Tracy Wilson Choreographer: Jeffrey Buttle, Shae-Lynn Bourne Former Coach: Nanami Abe, Shoitirou Tuzuki Practice low season: h / week at Toronto/CAN Practice high season: h / week at Toronto/CAN Music Short Program / Short Dance as of season 2014/2015 Ballade No. 1 op. 23 in G minor by Frederic Chopin Music Free Skating / Free Dance as of season 2014/2015 Phantom of the Opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber Personal Best Total Score 293.25 06.12.2013 ISU Grand Prix Final 2013/14 Personal Best Score Short Program 101.45 13.02.2014 XXII Olympic Winter Games 2014 Personal Best Score Free Skating 194.08 13.12.2014 ISU Grand Prix Final 2014/15 07/08 08/09 09/10 10/11 11/12 12/13 13/14 14/15 Olympic Games 1. World Champ. 3. 4. 1. 2. European Champ. Four Continents 2. 2. World Juniors 12. 1. National Champ. 3.J 1.J 1.J 4.S 3.S 1.S 1.S 1.S S=Senior; J=Junior; N=Novice International Competition Year Place International Competition Year Place ISU Grand Prix Final 2012/13 Sochi 2012 2. ISU Grand Prix Final 2013/14 Fukuoka 2013 1. Finlandia Trophy 2013 Espoo 2013 1. ISU GP Lexus Cup of China 2014 Shanghai 2014 2. ISU GP Skate Canada International 2013 Saint John, NB 2013 2.