The Twenty Fifth Tale of the Vetala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1 The most obvious characteristic at the supernatural world of the Kawaiisu is its complexity, which stands in striking contrast to the “simplicity” of the mundane world. Situated on and around the southern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains in south - - central California, the tribe is marginal to both the Great Basin and California culture areas and would probably have been susceptible to the opprobrious nineteenth century term, ‘Diggers’ Yet, if its material culture could be described as “primitive,” ideas about the realm of the unseen were intricate and, in a sense, sophisticated. For the Kawaiisu the invisible domain is tilled with identifiable beings and anonymous non-beings, with people who are half spirits, with mythical giant creatures and great sky images, with “men” and “animals” who are localized in association with natural formations, with dreams, visions, omens, and signs. There is a land of the dead known to have been visited by a few living individuals, and a netherworld which is apparently the abode of the spirits of animals - - at least of some animals animals - - and visited by a man seeking a cure. Depending upon one’s definition, there are apparently four types of shamanism - - and a questionable fifth. In recording this maze of supernatural phenomena over a period of years, one ought not be surprised to find the data both inconsistent and contradictory. By their very nature happenings governed by extraterrestrial fortes cannot be portrayed in clear and precise terms. To those involved, however, the situation presents no problem. Since anything may occur in the unseen world which surrounds us, an attempt at logical explanation is irrelevant. -

Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another

COMICS COSPLAY TV/FILM GAMES SUBMIT CGC Search … Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another Big Splash? Posted by Mark Seifert March 19, 2014 0 Comments Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Tumblr Email Reddit [The Manhattan Projects #18 has been out for a couple weeks, but still — if you haven’t read this issue and plan to, you might want to skip this post for now.] Several years into the digital era for both comics reading and comics production, I still love to look at original comic art up close. The look and feel of the art board, the subtle texture of the ink, the faint traces of changes and corrections… it all adds up to a little extra insight into the time and circumstances behind the comics book’s creation. We’ve mentioned a bunch of noteworthy original art sales here in recent times — from that awe-inspiring Golden Age Action Comics #15 cover by Fred Guardineer, to this Silver Age Fantastic Four #55 page by Jack Kirby, to this Bronze Age classic Amazing Spider- Man #121 cover by John Romita Sr, down to the current record holder for a piece of American comic book art with this Amazing Spider-Man #328 cover by Todd McFarlane. And increasingly, original art sales from much more recent comics are turning heads as well. It’s probably no surprise that Skottie Young original art is highly sought after, or that Walking Dead original art — even panel pages — can command some eye- popping prices. But modern comic art collectors have broadened their interests to many other artists and titles of quality in recent times, such as this Pia Guerra Y: The Last Man panel page that recently went for $1000. -

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas”

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas” Release Date: December 24, 2018 Running Time: 1 hour, 11 minutes Sally: Kay. Fuck, marry, kill. Sam, Dean, Cas. Emily: Ah, fu-- (laugh) Brie: I feel like that’s easy. (laugh) Emily: That’s super easy. Sally: I just -- we gotta start the episode somehow. Emily: OK, kill Sam, obviously. Brie: Duh. Yeah, no, duh. Yeah. Emily: Yeah. Brie: Yeah. Mm. Sally: (laugh) Emily: Uh, then I guess I’d marry Cas? Brie: Yeah … Sally: Fuck Dean? Emily: Yeah. Sally: That’s where I was sitting too. Brie: Yeah. Sally: So we’re all in agreement. Brie: Yeah. Emily: I just -- Cas actually has a personality I can stand. When he actually develops a personality, which is later, I guess, in the series. Sally: Yeah. Brie: I do think, though, that, like, the emotional parts of Dean -- Emily: Yeah. Brie: If that -- if that was, like, turned on all the time. Marry. Emily: My idealized version of Dean -- Brie: Yeah. Emily: I would marry. Brie: Yeah. Yeah. Emily: But the Dean that’s actually on the show? Mm-mm. Fuckin’ leave. Sally: OK! (all laugh) Emily, singing: Have a holly, jolly Christmas … Sally: Um, earlier I was reading an article called -- Brie: Oh! Oh, yeah. Yeah. Emily: Don’t repeat it. It’s the worst. Sally: (laughing) Emily: I know we’re an explicit podcast, but this might be the line of what’s too explicit. Brie: (laugh) Sally: K, it was an article about monster erotica, and the title of the article is also a title for the book. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

One and Three Bhairavas: the Hypocrisy of Iconographic Mediation Gregory Price Grieve

Revista de Estudos da Religião Nº 4 / 2005 / pp. 63-79 ISSN 1677-1222 One and Three Bhairavas: The Hypocrisy of Iconographic Mediation Gregory Price Grieve The artist-as-anthropologist, as a student of culture, has as his job to articulate a model of art, the purpose of which is to understand culture by making its implicit nature explicit. [T]his is not simply circular because the agents are continually interacting and socio-historically located. It is a non-static, in-the-world model. Joseph Kosuth1, “The Artist as Anthropologist” (1991[1975]) Iconography is a hypocritical term. On the face of it, “iconography” simply denotes the critical study of images (Panofsky 1939; 1955). Yet, one must readily admit that iconography stems from the fear of images (Mitchell 1987). In fact, iconography can be defined as a strategy for writing over images. But why fear images? Iconography’s zealotry—from idols made in the likeness of God to fetishes made in the image of capital—stems from the terror of the material. Accordingly, to proceed in an analysis of iconography, one must make explicit what most religious discursive systems must by necessity leave implict religion is never just “spirit.” Whether iconophobia or iconophilia, whether iconoclastic or idolatry, what all religions have in common is that they rely on matter for their dissemination. Even speech, the most reified communication, relies on air and the physicality of the human body. Accordingly, to write about, rather than write over, religious images, we need to return to the material. Stop and take a look at the god-image of Bhairava, a fierce form of Shiva from the Nepalese city of Bhaktapur2. -

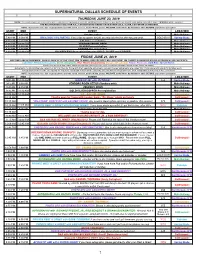

Supernatural Dallas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL DALLAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2019 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please VALIDATE at the Photo Op Validation table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 3:30 PM 7:45 PM Vendors set-up Main Hallway 7:00 PM 9:30 PM BRI & DICK 'S PJ PARTY!!! If you’d like to register tonight, you may join the line after the party ends. SOLD OUT! Spring Glade 7:45 PM 8:30 PM GOLD Pre-registration Main Hallway 7:45 PM 10:00 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Main Hallway 8:30 PM 9:00 PM SILVER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:00 PM 9:30 PM COPPER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:30 PM 10:00 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Main Hallway FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2019 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America. -

Story of King Vikramadhithya Contents

Story of king Vikramadhithya There are two versions to this great story. The north Indian version was called “Simhasan Bhatheesi(throne with 32 steps) and the south Indian version was called “Periya ezhuthu Vikramadhithan kadhai(The story of Vikramadhithya in big letters).I have followed the south Indian version, I have summarized the stories in to a very short form as the original stories are very lengthy , with very many descriptions. This is possibly the greatest gift to the Indian lads and lasses that I can give Contents Story of king Vikramadhithya ................................................................... 1 1. Bhoja Raja gets Vikramadithya’s throne .................................. 3 2. Who was Vikramadithya? ........................................................ 5 3. Vikramadhithya and Vetala –I ................................................ 12 4. Vikramadhithya and Vetala –IRetold by ................................ 14 5. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 2-6 ................................. 17 6. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 7-10 ............................... 24 7. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 11-16 ............................. 33 8. Vikramadhithya and Vetala stories 17-24 and story of Vetala ............................................................................................... 42 9. The story of Elalaramba told by the third doll -Komalavalli .. 56 10. The story of Chamapakavalli as told by fourth doll Mangala Kalyana Valli. ......................................................................... -

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

![The Essential Supernatural [Revised and Updated Edition]: on the Road with Sam and Dean Winchester Pdf, Epub, Ebook](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4427/the-essential-supernatural-revised-and-updated-edition-on-the-road-with-sam-and-dean-winchester-pdf-epub-ebook-1434427.webp)

The Essential Supernatural [Revised and Updated Edition]: on the Road with Sam and Dean Winchester Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ESSENTIAL SUPERNATURAL [REVISED AND UPDATED EDITION]: ON THE ROAD WITH SAM AND DEAN WINCHESTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Knight, Eric Kripke | 232 pages | 07 Jan 2015 | Insight Editions | 9781608875023 | English | San Rafael, United States The Essential Supernatural [Revised and Updated Edition]: On the Road with Sam and Dean Winchester PDF Book Nice to read the cast's thoughts on their characters, crew, and episodes. Join them as they hunt all those things that go bump in the night, seek vengeance on the Yellow-Eyed Demon that killed their parents, deal with the Knights of Hell, and stop the bona fide Apocalypse! It came quick and very good condition. See how a store is chosen for you. Other editions. Best www. Get A Copy. Loved this. This tome is a complete and very detailed breakdown of the stories from each season. Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Second, I much prefer watching the TV Series than reading about it. This item may be a floor model or store return that has been used. Filled with interviews with the cast and crew of the hit show, stunning behind-the-scenes-imagery and art, and a wealth of thrilling removable items, this updated version includes new chapters on seasons 8 and 9 and a preview of the upcoming season Nice break down of the episodes from seasons Go back on the road with Sam and Dean Winchester in this revised and updated edition of the best-selling The Essential Supernatural. This deluxe edition dissects the show season by season, state by state, tracking the Winchester brothers as they travel across the U.