State Highway Investment in New Zealand the Decline and Fall of Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research to Understand the Planning Risks Associated with the Kapiti Expressway (Rons)

Research to Understand the Planning Risks Associated with the Kapiti Expressway (RoNS) April 2011 Andrew Guerin and Kirsty van Reenen (MWH) January 2011 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Purpose 4 3. Methodology 3.1 Lifting of LAR and potential plan changes 5 3.2 Expressway Interchanges 6 4. Development Potential 4.1 Lifting of LAR status on SH1 7 4.2 Under potential plan changes 8 4.3 In relation to expressway interchanges 9 4.3.1 Introduction 9 4.3.2 Otaki North 9 4.3.3 Otaki South 10 4.3.4 Peka Peka Road 10 4.3.5 Waikanae 11 4.3.6 Poplar Avenue 11 4.3.7 Summary 12 5. Overall Findings 13 6. Development potential in relation to Waikanae North 15 6.1 Introduction 15 6.2 Existing district plan provisions 17 6.3 Reduction in development potential 19 7. Demand Side Factors 22 8. Recommendations 23 Appendix 1 Planning around interchange areas Appendix 2 National/international best practice Appendix 3 Growth Management Strategies Appendix 4 Extract from NZTA’s PPM Appendix 5 Implications of removing LAR January 2011 2 1. Introduction The New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) proposes to replace the current State Highway 1 (SH1) with a four lane expressway. NZTA are in the process of designing and planning for the construction of a four lane expressway through the district in four stages from Transmission Gully northwards (Transmission Gully (Linden to Mackays), Mackays to Peka Peka, Peka Peka to Otaki and Otaki to Levin). It is likely that the regional consents, NZHPT archaeological applications and Notices of Requirement applications will be lodged with the Environmental Protection Agency in late 2011/ early 2012. -

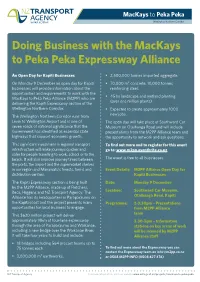

Doing Business with the Mackays to Peka Peka Expressway Alliance

MacKays to Peka Peka Wellington Northern Corridor Doing Business with the MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Alliance An Open Day for Kapiti Businesses • 2,500,000 tonnes imported aggregate. On Monday 9 December an open day for Kapiti • 70,000 m³ concrete. 10,000 tonnes businesses will provide information about the reinforcing steel. opportunities and requirements to work with the • 45 ha landscape and wetland planting MacKays to Peka Peka Alliance (M2PP) who are (over one million plants). delivering the Kapiti Expressway section of the Wellington Northern Corridor. • Expected to create approximately 1000 new jobs. The Wellington Northern Corridor runs from Levin to Wellington Airport and is one of The open day will take place at Southward Car seven roads of national significance that the Museum on Otaihanga Road and will include Government has identified as essential state presentations from the M2PP Alliance team and highways that support economic growth. the opportunity to network and ask questions. This significant investment in regional transport To find out more and to register for this event infrastructure will make journeys quicker and go to: www.m2pp.eventbrite.co.nz safer for people travelling to work, school or to the beach. It will also improve journey times between The event is free to all businesses. the ports, the airport and the supermarket shelves in our region and Manawatu’s forests, farms and Event Details: M2PP Alliance Open Day for distribution centres. Kapiti Businesses The Kapiti Expressway section is being built Date: Monday 9 December by the M2PP Alliance, made up of Fletchers, Beca, Higgens and NZ Transport Agency. -

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012 For more information, contact: Greater Wellington Published September 2012 142 Wakefield Street GW/CP-G-12/226 PO Box 11646 Manners Street [email protected] Wellington 6142 www.gw.govt.nz T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 Western Corridor Plan Strategic Context Corridor plans organise a multi-modal response across a range of responsible agencies to the meet pressures and issues facing the region’s land transport corridors over the next 10 years and beyond. The Western Corridor generally follows State Highway 1 from the regional border north of Ōtaki to Ngauranga and the North Island Main Trunk railway to Kaiwharawhara. The main east- west connections are State Highway 58 and the interchange for State Highways 1 and 2 at Ngauranga. Long-term vision This Corridor Plan has been developed to support and contribute to the Regional Land Transport Strategy (RLTS), which sets the objectives and desired outcomes for the region’s transport network. The long term vision in the RLTS for the Western Corridor is: Along the Western Corridor from Ngauranga to Traffic congestion on State Highway 1 will be Ōtaki, State Highway 1 and the North Island Main managed at levels that balance the need for access Trunk railway line will provide a high level of access against the ability to fully provide for peak demands and reliability for passengers and freight travelling due to community impacts and cost constraints. within and through the region in a way which Maximum use of the existing network will be achieved recognises the important strategic regional and by removal of key bottlenecks on the road and rail national role of this corridor. -

Draft Wellington Regional Land Transport Plan 2015

8. STRATEGIC ROAD NETWORK 8.1 INTRODUCTION What is the One Network Road The strategic road network forms the backbone of the Classification (ONRC)? region’s transport network. It comprises the state highways and some higher volume local roads. It serves an important role for both inter-regional long distance trips and short The ONRC involves categorising roads based on the to medium distance trips within the region, and provides primary function(s) they perform access and connectivity for people and goods to key regional The ONRC is a nationally consistent classification destinations (such as Wellington CBD, CentrePort, the system for the state highway and local road network regional hospital and international airport) as well as links between key regional centres. It has been formally adopted by NZ Transport Agency for use in the development of the NLTP 2015-18 Investment in the strategic road network is just one element of the wider plan for improving the region’s It helps inform decisions about the associated customer transport network, and needs to be considered as part of an level of service that a particular category of road should integrated planning and investment approach. offer. Network Plans 8.2 WELLINGTON’S STRATEGIC ROAD NETWORK The strategic road network has been defined as those routes meeting the criteria for the top three tiers of the The existing strategic road network comprises: One Network Road Classification – ‘National High Volume Roads’, ‘National Roads’, and ‘Regional Roads’. • SH1 from Wellington Airport to just -

TRANSCRIPT of PROCEEDINGS BOARD of INQUIRY Mackays To

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS BOARD OF INQUIRY MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Proposal HEARING at KAPITI COAST on 14 JANUARY 2013 BOARD OF INQUIRY: Sir John Hansen (Chairperson) Environment Commissioner David Bunting (Board Member) Ms Glenice Paine (Board Member) Mr Mark Apeldoorn (Board Member) Page 2084 [9.29 am] CHAIRPERSON: Thank you. Good morning, just to remind submitters before 5 we start that this is an opportunity to speak to the submissions that have already been filed and I think the first, Ms Hawken and Mr Mansfield. MS HAWKEN: Thank you, your Honour, and members of the Board for giving me this opportunity to speak about the expressway proposal. 10 My name is Dinah Hawken and I live in Paekakariki because of the quiet and the beauty of the coastal environment and the satisfactions of living in a small community. I identify strongly with others who live on the Kapiti Coast for the same reasons and who would be affected by the building of an expressway through their neighbourhoods. 15 I have worked as a social worker and counsellor. I am also a poet and have recently been teaching a course at Victoria University called “Writing the Landscape”. I am grateful that you are hearing personal and general responses to the proposal because I think the whole range 20 of opinion from the most technical and detailed to the most broad and personal are relevant and of value. [9.30 am] 25 I will give my reactions in a brief and forthright way knowing that you are also hearing many other points of view. -

JL Evidence WLR-8 OCT-VC

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Proposal UNDER The Resource Management Act 1991 IN THE MATTER of: Notice of requirement for designation and resource consent applications by the NZ Transport Agency for the MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Proposal APPLICANT NZ Transport Agency STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF JAMES LUNDAY (Urban Planning and Design) for Save Kapiti Dated: 8th October 2012 INTRODUCTION Expert Witness 1. My name is James Lunday. I hold the qualifications of Diploma of Architecture, Bachelor of Arts with First Honours, Bachelor of Planning with First Honours, a Diploma of Urban Design and a Masters of Urban Design (Distinction) both from Oxford Brookes. I have 35 years experience in Architecture, Strategic Planning, Heritage Planning, Urban Regeneration and Urban Design having worked in Government, Academic and Private Sector roles. 2. I have held the positions of Architect for City of Glasgow, Urban Designer/Landscape Planner for the State Government of Victoria, Australia, Director of Urban Regeneration for the Civic Trust, UK, Executive Director of the Auckland Heritage Trust, Senior Lecturer at University of Auckland, and Principal of Common Ground Studio. 3. I have been a practicing Urban Designer since 1982, when I was appointed to the position of Urban Designer and Landscape Planner for the Ministry for Planning and Environment, Victoria, Australia. During this time I was involved in the restructuring of Melbourne with a focus on infrastructure / land-use led economic recovery with aim of creating Melbourne as the most Livable City in Australia. 4. In 1985 I returned to Europe from Australia to take up the position of Project Director of Regeneration for the Civic Trust, London, in charge of Urban Renewal Projects. -

Trimble Connected Site Solutions Drive Productivity for Fletcher Infrastructure’S New Zealand Kapiti Expressway Build

TRIMBLE CONNECTED SITE SOLUTIONS DRIVE PRODUCTIVITY FOR FLETCHER INFRASTRUCTURE’S NEW ZEALAND KAPITI EXPRESSWAY BUILD TRIMBLE CONNECTED SITE PORTFOLIO, INCLUDING ON AND OFF MACHINE TRIMBLE TECHNOLOGY, TIGHTLY CONNECTS OFFICE AND FIELD BASED OPERATIONS Overview The MacKays to Peka Peka (M2PP) Expressway project is being built by an alliance made up of the New Zealand (NZ) Transport Agency, Beca Planning and Infrastructure, Fletcher Construction. The M2PP Alliance brings together a high performing, integrated team to address this project's complex design, construction, environmental and lifecycle issues. It’s a model of contracting that has been successfully used around the world to deliver complex and challenging infrastructure projects. The Wellington Northern Corridor is one of seven Source: NZ Transport Agency http://www.nzta.govt.nz/projects/mackays-to-peka-peka/ ‘roads of national significance’ that the New Zealand Government has identified as essential state highways, In total, the $630 million NZD ($488 million USD) which have been selected for upgrades. According to project will deliver approximately 18 kilometers [11.2 the NZ Transportation Agency, the goal of the miles] of four-lane expressway through Kapiti, upgrading efforts is to reduce congestion, improve including a new bridge over the Waikanae River. To public safety and stimulate economic growth in the build the expressway, Fletcher Construction, region. subcontractor Goodmans have been tasked with Fletcher Construction is a leading infrastructure, moving 3.5 million cubic meters [123 million cubic commercial engineering and building contractor, feet] of dirt, including more than 800,000 cubic meters developing projects in New Zealand and the South [28 million cubic feet] of peat. -

Colliers NZ Research Report

1 February 2020 The Big New Zealand Upgrade In late 2019 the government announced a $12 billion injection for infrastructure. In late January 2020, $6.8 billion of transport projects were announced as part of the Big New Zealand Upgrade. We detail the projects and consider the influences. While there is still $4 billion of announcements to come, the latest announcement shows a significant emphasis on roading infrastructure, accounting for $5.6 billion, or just over 80% of the transport programme. Auckland will receive around $3.5 billion or 52% of the transport programme. Some of the projects are a continuation of existing or previously investigated projects. Of the 20 projects announced, 55% are expected to commence construction by the end of 2021. Many of the projects (60%) are forecast to complete in 2024 and 2025. Funding Location Type Project Start Completion ($000s) Northland $692 Road Four-lane 22km corridor with separated shared walking and cycling path 2023/24 2025/26 Penlink: two-lane, tolled 7km corridor with separated shared walking and Auckland $411 Road Late 2021 Late 2025 cycling path $1,354 Road Mill Road: four-lane corridor with separated walking and cycling path Late 2022 2025/26 Papakura to Drury South: add a third lane in each direction, interchange $423 Road improvements shared walking and cycling path and allowing future dedicated Late 2020 Late 2025 public transport services Northern Pathway: 2km shared path over the Auckland harbour Bridge with $360 Road Early 2021 2023/24 3km of shared path from Northcote to Esmonde -

Progress Report on Projects in the Regional Land Transport Plan 2015

Report 15.582 Date 20 November 2015 File TP/01/18/18 Committee Regional Transport Committee Author Patrick Farrell, Transport Planner Progress report on projects in the Regional Land Transport Plan 2015 1. Purpose To update the Committee on the current status and progress in relation to the large new projects included and prioritised in the Regional Land Transport Plan 2015 and any other progress of note. 2. Background The Regional Land Transport Plan 2015 (RLTP) is a statutory document developed under the Land Transport Management Act 2003. It sets out the policy framework for development of the region’s transport network over the next 10-30 years. The RLTP also contains all the land transport activities proposed to be undertaken over 6 financial years, and the regional priority of significant activities (costing >$5m). The activities in the RLTP are submitted by the NZ Transport Agency and ‘Approved Organisations’ (including the eight territorial authorities and Greater Wellington Regional Council – GWRC). 3. Monitoring the RLTP A description of how monitoring will be undertaken to assess implementation of the RLTP is set out in Appendix A of the plan. The key monitoring elements are: • Projects – a half yearly report on the status of significant projects and other projects of regional interest • Outcomes/targets – an annual report on progress against outcomes and targets (full report every three years, summary report in intervening years) This report fulfils the first of the two monitoring elements above and focuses on project progress over the past 6 months. 4. Comment The progress detailed in sections 4.4 to 4.6 of this report is for projects and activities due to commence in 2015/16. -

Policy Guidelines for Integrated Sustainable Transport Planning to Meet Greenhouse Gas Targets for Wellington, New Zealand An

“Policy Guidelines for Integrated Sustainable Transport Planning to meet Greenhouse Gas Targets for Wellington, New Zealand and Possible Effects on the Built Environment” Rehan P. Shaikh School of Architecture Faculty of Architecture and Design Victoria University Wellington. POLICY GUIDELINES FOR INTEGRATED SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT PLANNING TO MEET GREENHOUSE GAS TARGETS FOR WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND AND POSSIBLE EFFECTS ON THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT By Rehan Pervez Shaikh Primary Supervisor; Prof. Robert Vale Secondary Supervisor; Dr. Nigel Isaacs A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Architecture Faculty of Architecture and Design Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand 2019 “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them” Albert Einstein Abstract The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the Earth's atmosphere is resulting in an increase in the temperature of the Earth. The accumulation of GHGs is due to emissions from burning of fossil fuels for energy generation and transportation, from industrial and manufacturing processes, as well as from agriculture and other activities. To meet the requirements of the Paris Climate Agreement, to which New Zealand is a signatory, will require emissions to be cut by at least 80% from current levels by or before 2050. The transport sector through its reliance on oil accounts for approximately 15% of overall greenhouse gas emissions. Global CO2 emissions from transport have grown by 45% from 1990 to 2007. At the same time the International Energy Agency (2013) state that by 2050 under a Business-as-Usual scenario global urban passenger mobility will more than double. -

Kapiti Coast District CWB Network Planning

622705 Report Kapiti Coast District CWB Network Planning Prepared for Kapiti Coast District Council Prepared by Beca Limited 11 February 2015 622705 Kapiti Coast District CWB Network Planning Revision History Revision Nº Prepared By Description Date 1 Christopher Carlaw First draft to client 8/9/14 2 Alan Kerr Second draft following Council workshop 20/10/14 3 Chris Carlaw Third draft incorporating client comment 11/2/15 4 5 Document Acceptance Action Name Signed Date Prepared by Christopher Carlaw Reviewed by Alan Kerr Approved by Alan Kerr on behalf of © Beca 2013 (unless Beca has expressly agreed otherwise with the Client in writing). This report has been prepared by Beca on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Any use or reliance by any person contrary to the above, to which Beca has not given its prior written consent, is at that person's own risk. Beca // 11 February 2015 3819639 // NZ1-9518816-17 0.17 // i 622705 Kapiti Coast District CWB Network Planning Executive Summary Kapiti Coast District Council has appointed Beca to undertake an assessment of the Cycleway, Walkway, Bridleway (CWB) Network across the district with a view to producing an overall strategy for the development of the network including an aspirational plan for the complete future network. The network planning methodology has had a significant focus on gauging stakeholder concerns and comments about the future infrastructure for the district. In the context of this project, the data received from stakeholders, the community, Council and site visits has been used to target locations for improvements, however, like all local engagement it is subjective and open to individual interpretation. -

The Kāpiti Distressway’: a Sociological Case Study of Public

‘The Kāpiti Distressway’: A Sociological Case Study of Public Involvement in a Socio-Technical Controversy BY Morgan Jasper Hamlin A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines public involvement in socio-technical controversies from a sociological perspective. Public engagement in science and technology is becoming increasingly important in societies where citizens are asked, and expected, to be involved with issues that have been dominated by experts. In New Zealand, a contemporary example of public participation in science and technology is the large-scale road building programme called the Roads of National Significance. The central aim of this thesis is to understand how the public engage with and create meaningful evaluations of complex issues that are associated with expert- driven politics and top-down decision-making processes. I examine the public’s involvement in the Kāpiti expressway project by discussing how locally-based groups evaluated and publicised it as an object of concern. Specifically, I investigate the demonstration and visual imagery technologies that were utilised to publicise the expressway as a public matter. I then explore how opponents translated their concerns with the environmental, political, and social aspects of the project as legal and technical issues. The second aim of this thesis is to contribute to the material turn in the human sciences by engaging with object-oriented (Barry, 2013; Latour, 2005a; Marres & Lezaun, 2011) and socio-cultural (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006) approaches to public involvement in socio-technical controversies.