FTF-T HFLG EAS Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Ground up Case Studies in Community Empowerment

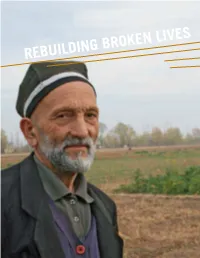

REBUILDING BROKEN LIVES After gaining Independence in 1991, Tajikistan endured economic collapse, civil war, and widespread hunger. To help rural people back on their feet, ADB financed a pilot microcredit-based livelihood project for women and farmers. Implemented through two international NGOs, the Aga Khan Foundation and CARE International, the experiment encountered many challenges, but produced several positive outcomes The women’s group composes a peaceful scene, without a hint of the tumultuous circumstances that spawned it. In a drab building in Vahdat district in western Tajikistan, a dozen women, mostly young, are bent over a long table, their fingers busy with embroidery. Along a wall behind them, older women are stitching a floral- patterned kurpacha, the thick, multipurpose Tajik quilt. Some of the girls are teenagers, who are only dimly aware of the horrors that followed Tajikistan’s unsought independence in 1991. But Zebo Oimatova, 52, a benevolent figure in traditional kurta (robe) and headscarf who is watching over the room like a mother hen, remembers it all—economic ruin, villages torn apart by civil war, the hardscrabble existence and, finally, a chance to rebuild shattered lives. In 2002, Ms. Oimatova, a warm-hearted woman of simple sincerity, was elected chairperson of a women’s federation, a community-based organization created under a pilot Asian Development Bank (ADB)-financed project to provide microcredit for women to start small businesses and farmers to improve crops. Despite being overawed—“I thought I could not manage the job because I am only average and not so well educated,” she confesses—Ms. Oimatova has seen her group grow from a handful to over 2,500 members and, importantly, become self-sufficient. -

Land Und Leute 22

Vorwort 11 Herausragende Sehenswürdigkeiten 12 Das Wichtigste in Kurze 14 Entfernungstabelle 20 Zeichenlegende 20 LAND UND LEUTE 22 Tadschikistan im Überblick 24 Landschaft und Natur 25 Gewässer und Gletscher 27 Klima und Reisezeit 28 Flora 29 Fauna 32 Umweltprobleme 37 Geschichte 42 Die Anfänge 42 Vom griechisch-baktrischen Reich bis zur Kushan-Dynastie 47 Eroberung durch die Araber und das Somonidenreich 49 Türken, Mongolen und das Emirat von Buchara 49 Russischer Einfluss und >Great Game< 50 Sowjetische Zeit 50 Unabhängigkeit und Burgerkrieg 52 Endlich Frieden 53 Tadschikistan im 21. Jahrhundert 57 Regierung 57 Wirtschaftslage 58 Kritik und Opposition 58 Tourismus 60 Politisches System in Theorie und Praxis 61 Administrative Gliederung 63 Wirtschaft 65 Bevölkerung und Kultur 69 Religionen und Minderheiten 71 Städtebau und Architektur 74 Volkskunst 77 Sprache 79 Literatur 80 Musik 85 Brauche 89 http://d-nb.info/1071383132 Feste 91 Heilige Statten 94 Die tadschikische Küche 95 ZENTRALTADSCHIKISTAN 102 Duschanbe 104 Geschichte 104 Spaziergang am Rudaki-Prospekt 110 Markt und Mahalla 114 Parks am Varzob-Fluss 115 Museen 119 Denkmaler 122 Duschanbe live 128 Duschanbe-Informationen 131 Die Umgebung von Duschanbe 145 Festung Hisor 145 Varzob-Schlucht 148 Romit-Tal 152 Tal des Karatog 153 Wasserkraftwerk Norak 154 Das Rasht-Tal 156 Ob-i Garm 158 Gharm 159 Jirgatol 159 Reiseveranstalter in Zentral tadschikistan 161 DER PAMIR 162 Das Dach der Welt 164 Ein geografisches Kurzportrait 167 Die Bewohner des Pamirs 170 Sprache und Religion 186 Reisen -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized Nurek Hydropower Rehabilitation Project Phase 2 Republic of Tajikistan

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized Nurek Hydropower Rehabilitation Project Phase 2 Republic of Tajikistan May 2020 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Nurek HPP Rehabilitation Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the ESIA ............................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Organization of the ESIA ....................................................................................................... 3 2 Project description .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Description of Nurek HPP ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 The Project ............................................................................................................................ 7 Dam Safety ............................................................................................................... 9 Details of work to be performed ............................................................................. 9 Refurbishment -

Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 49042-005 (DRAFT) January 2018 TAJ: CAREC Corridors 2, 5, and 6 (Dushanbe– Kurgonteppa) Road Project–Additional Financing (Part 1) Prepared by the KOCKS Consult GmbH for the Asian Development Bank and the Ministry of Transport of Tajikistan. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ЧУМ ХУРИИ ТОЧИКИСТОН РЕСПУБЛИКА ТАДЖ ИКИСТАН МАРКАЗИ ТАТБИ^И ЛОИХДДОИ ЦЕНТР РЕАЛИЗАЦИИ ПРОЕКТО! ТАЧДИДИ РОХДО РЕАБИЛИТАЦИИ ДОРОГ REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN PROJECTS IMPLEMENTATION UNIT FOR ROADS REHABILITATI O N __ ш . Душ анбе, кучаи Айнй 14 14 Ayni str., Dushanbe г. Д уш анбе, улица А йни 14 Т ел /Ф ак с: (992 37) 222 20 73 Tel/Fax: (992 37) 222 20 73 Т ел/Ф акс: (992 37) 222 20 73 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: piumajbk.ru E-mail: piur r @ b k .r u 14- О / - / X __________ № 4oG Mr. Dong Soo Pyo Director Transport and Communications Division Central & West Asia Department Asian Development Bank PNo.49042-005: CAREC Corridors 2, 5, and 6 (Dushanbe - Kurgonteppa) Road Project - Additional Financing Subject: Draft Initial Environmental Examination (IEE). -

Pdf | 336.56 Kb

RAPID EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT AND COORDINATION TEAM (REACT) Floods in Khatlon: 7 – 13 May 2021 Situation Report # 1 (as of 14 May 2021) Highlights - Over 12 mudflows and landslides have been reported during the period of 7 – 13 May 2021. - Mudflows caused the death of 9 people. - Over 70 households are left homeless. - Large number of cattle has been lost and agricultural crops destroyed. - Mudflows caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people Situation Overview The torrential rains of 7 – 12 May 2021 triggered floods, landslides and mudflows in many of the country’s districts. The largest number of losses and destructions are faced by districts and cities of Khatlon province. Disasters affected following cities and districts: Kulob city and districts of Shamsiddini Shohin, Qushoniyon, Dangara, Yovon, Khuroson, Dusti, Vaksh, Muminobod and Jomi (please refer to Map below). CoES reports that disasters caused the death 9 people. Very preliminary estimates indicate that 74 households were left homeless and houses of another 270 households were damaged to different extent. Very modest estimations indicate damages caused by disasters to private and social infrastructure caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people. Government of Tajikistan activated an Inter-Agency Commission on Emergency Situations (Commission) in each disaster affected district, which fully facilitates the response operations. Furthermore, Emergency Operations Centers (Shtab) have been set up in each disaster affected district, which collects and analyzes relevant information and coordinates the response activities. Up to date, general response actions in every district include: search and rescue, evacuation of population from risk zones, constant disinfection of the affected territories, debris removal, assessment of damages and needs, registration of affected population, restoration of communal services, collection and distribution of immediate relief assistance, as well as recovery planning. -

Country Portfolio Evaluation Tajikistan (1999 – 2015) Volume Ii - Technical Documents

GEF/ME/C.50/Inf 04 June3, 2016 50th GEF Council Meeting June 7 – 9, 2016 Washington, D.C. COUNTRY PORTFOLIO EVALUATION TAJIKISTAN (1999 – 2015) VOLUME II - TECHNICAL DOCUMENTS (Prepared by the Independent Evaluation Office of the GEF) TABLE OF CONTENTS A Country Environmental Legal Framework .............................................................................. 1 B Global Environmental Benefits Assessment ................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. C Progress toward Impact – Case Studies ................................................................................ 80 I Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Development in the Gissar Mountains of Tajikistan ....................................................................................................................... 85 II Community Agriculture and Watershed Management .................................................. 111 III Demonstrating Local Responses to Combating Land Degradation and Improving Sustainable Land Management in SW Tajikistan under the CACILM Partnership Framework, Phase 1 ........................................................................................................ 131 ANNEX 1 - Photo log ..................................................................................................................... 153 i TECHNICAL DOCUMENT A – COUNTRY ENVIRONMENT LEGAL FRAMEWORK 1 Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank BCAP Biodiversity Conservation Action Plan Committee for Environmental CBD Convention on Biological Diversity -

Annual Report

FUNDED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IMPLEMENTED BY THE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME With financial support from the Russian Federation ANNUAL REPORT ON IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS OF THE PROJECT “LIVELIHOOD IMPROVEMENT OF RURAL POPULATION IN 9 DISTRICTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN” FROM JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 2017 Dushanbe 2017 1 Russian Federation-UNDP Trust Fund for Development (TFD) Project Annual Narrative and Financial Progress Report for January 1 – December 31, 2017 Project title: "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan" Project ID: 00092014 Implementing partner: United Nations Development Programme, Tajikistan Project budget: Total: 6,700,000 USD TFD: Government of the Russian Federation: 6,700,000 USD Project start and end date: November 2014 – December 2017 Period covered in this report: 1st January to 31st December 2017 Date of the last Project Board 17th January 2017 meeting: SDGs supported by the project: 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Please provide a short summary of the results, highlighting one or two main achievements during the period covered by the report. Outline main challenges, risks and mitigation measures. The project "Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in 9 districts of the Republic of Tajikistan", is funded by the Government of the Russian Federation, and implemented by UNDP Communities’ Program in the Republic of Tajikistan through its regional offices. Project target areas are Isfara, Istaravshan, Ayni, Penjikent in Sughd region; Vose and Temurmalik in Khatlon region; Rasht, Tojikobod and Lakhsh (Jirgatal) in the Districts of Republican Subordination (DRS). The main objective of the project is to ensure sustainable local economic development of the target districts of Tajikistan. -

IMAS - 2017 MEDAL DISTRIBUTION No City School Surname Name Grade Points Place 1 Ч

IMAS - 2017 MEDAL DISTRIBUTION No City School Surname Name Grade Points Place 1 Ч. Расулов МТМУ №5 TEMUROV MUHAMMADALI 6 100 Gold 2 Dushanbe Hotam PV HASANOV MUHAMMADJON 6 98 Gold 3 Dushanbe LIP KHAFIZOV PARVIZ 6 96 Gold 4 Dushanbe Hotam PV ASOEV BEZHAN 6 96 Gold 5 Хучанд МТМУ №12 ISKHAKI SAIDNEMATKHON 6 94 Silver 6 Dushanbe Hotam PV KHUJAMOV ASADBEK 6 91 Silver 7 Dushanbe Hotam PV TADZHIBAEVA MUKADDAS 6 88 Silver 8 Хучанд Гулчини маърифат JURABOEV AKRAMKHON 5 88 Silver 9 Dushanbe Hotam PV AMONOV AHLIDDIN 6 86 Silver 10 Dushanbe IPS ZARIPOV VAFO 5 86 Silver 11 Хучанд Литсейи №1 MALLOKHUJAEV ISFANDIYOR 5 86 Silver 12 Конибодом М/Х Чураев UMAROV BEHRUZ 5 86 Silver 13 Dushanbe Hotam PV KHOTAMOV SULAYMON 6 84 Bronze 14 Кулоб м. Президента POSHOQULOV AZIMJON 6 84 Bronze 15 Бустон Гимназияи №1 MUKHAMEDOV FIRDAVS 6 84 Bronze 16 Dushanbe School №20 GULOMJANOVA TAISIA 5 81 Bronze 17 Конибодом М/Х Чураев OBIDOV MUHAMMADAMIN 5 81 Bronze 18 Dushanbe Hotam PV HAKIMJONOV MUHAMMAD 6 79 Bronze 19 Dushanbe Hotam PV ABDULLOEV SARVAR 6 76 Bronze 20 Dushanbe Lyceum №2 KHUSRAVBEKOVA RUHAFZO 6 76 Bronze 21 Dushanbe Hotam PV SHARIPOV JAHONGIR 6 76 Bronze 22 Dushanbe Hotam PV MUKHTAROV AZAMAT 5 76 Bronze 23 Истаравшан Литсейи №1 SAYFIDDINOV SHOHRON 5 76 Bronze 24 Исфара Литсейи №5 GOIBNAZOV HAMIDULLOH 5 76 Bronze 25 Dushanbe Hotam PV SAIDOVA SALTANAT 4 76 Bronze 26 Исфара Мактаби №65 SHUKUROV SHAHZOD 4 76 Bronze 27 Dushanbe Hotam PV DEHOTI FARIZ 6 69 28 Dushanbe Innovation AHMEDJONOV FARRUKH 6 69 29 Хучанд Литсейи №1 ABDURAZOKOV MUHAMMADJON 6 69 30 Хучанд Литсейи