TIME to Lieutenant Colonel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Apr 06.Qxp

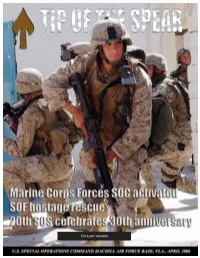

On-Line version TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 18 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 21 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 24 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 30 Special Operations Forces History Page 34 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command historic activation Gen. Doug Brown, commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, passes the MARSOC flag to Brig. Gen. Dennis Hejlik, MARSOC commander, during a ceremony at Camp Lejune, N.C., Feb. 24. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Marines run out of cover during a short firefight in Ar Ramadi, Iraq. The foot patrol was attacked by a unknown sniper. Courtesy photo by Maurizio Gambarini, Deutsche Press Agentur. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Special Forces trained Iraqi counter terrorism unit hostage rescue mission a success, page 7 SF Soldier awarded Silver Star for heroic actions in Afghan battle, page 14 20th Special Operations Squadron celebrates 30th anniversary, page 24 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

Mini-SITREP XXXIV

mini-SITREP XXXIV Eldoret Agricultural Show - February 1959. HM The Queen Mother inspecting Guard of Honour provided by ‘C’ Company commanded by Maj Jock Rutherford [KR5659]. Carrying the Queen Mother’s Colour Lt Don Rooken- Smith [KR5836]. Third from right wearing the Colorado Beetle, Richard Pembridge [KR6381] Edited and Printed by the Kenya Regiment Association (KwaZulu-Natal) – June 2009 1 KRA/EAST AFRICA SCHOOLS DIARY OF EVENTS: 2009 KRA (Australia) Sunshine Coast Curry Lunch, Oxley Golf Club Sun 16th Aug (TBC) Contact: Giles Shaw. 07-3800 6619 <[email protected]> Sydney’s Gold Coast. Ted Downer. 02-9769 1236 <[email protected]> Sat 28th Nov (TBC) East Africa Schools - Australia 10th Annual Picnic. Lane Cove River National Park, Sydney Sun 25th Oct Contact: Dave Lichtenstein 01-9427 1220 <[email protected]> KRAEA Remembrance Sunday and Curry Lunch at Nairobi Clubhouse Sun 8th Nov Contact: Dennis Leete <[email protected]> KRAENA - England Curry Lunch: St Cross Cricket Ground, Winchester Thu 2nd Jul AGM and Lunch: The Rifles London Club, Davies St Wed 18th Nov Contact: John Davis. 01628-486832 <[email protected]> SOUTH AFRICA Cape Town: KRA Lunch at Mowbray Golf Course. 12h30 for 13h00 Thu 18th Jun Contact: Jock Boyd. Tel: 021-794 6823 <[email protected]> Johannesburg: KRA Lunch Sun 25th Oct Contact: Keith Elliot. Tel: 011-802 6054 <[email protected]> KwaZulu-Natal: KRA Saturday quarterly lunches: Hilton Hotel - 13 Jun, 12 Sep and 12 Dec Contact: Anne/Pete Smith. Tel: 033-330 7614 <[email protected]> or Jenny/Bruce Rooken-Smith. Tel: 033-330 4012 <[email protected]> East Africa Schools’ Lunch. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

FOR ENGLAND August 2018

St GEORGE FOR ENGLAND DecemberAugust 20182017 In this edition The Murder of the Tsar The Royal Wedding Cenotaph Cadets Parade at Westminster Abbey The Importance of Archives THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF St. GEORGE – The Premier Patriotic Society of England Founded in 1894. Incorporated by Royal Charter. Patron: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II £3.50 Proud to be working with The Royal Society of St. George as the of cial printer of "St. George for England". One of the largest printing groups in the UK with six production sites. We offer the following to an extensive portfolio of clients and market sectors: • Our services: Printing, Finishing, Collation, Ful lment, Pick & Pack, Mailing. • Our products: Magazines, Brochures, Lea ets, Catalogues and Training Manuals. • Our commitment: ISO 14001, 18001, 9001, FSC & PEFC Accreditation. wyndehamgroup Call Trevor Stevens on 07917 576478 $$%# #%)( $#$#!#$%( '#$%) # &%#% &#$!&%)%#% % !# %!#$#'%&$&#$% % #)# ( #% $&#%%%$% ##)# %&$% '% &%&# #% $($% %# &%% ) &! ! #$ $ %# & &%% &# &#)%'%$& #$(%%(#)&#$'!#%&# %%% % #)# &%#!# %$ # #$#) &$ $ #'%% !$$ %# & &# ## $#'$(# # &"&%)*$ &#$ # %%!#$% &$ ## (#$ #) &! ! '#)##'$'*$)#!&$'%% $% '#%) % '%$& &#$% #(##$##$$)"&%)$!#$# # %#%$ # $% # # #% !$ %% #'$% # +0 +))%)$ -0$,)'*(0&$'$- 0".+(- + "$,- + $(("&()'*(0) ( "$,- + #+$-0) "$,- + !!$ (+ ,,!)+)++ ,*)( ( # -.$))*0#)&+'0+)/ )+$(" -# $(" Contents Vol 16. No. 2 – August 2018 Front Cover: Tower Bridge, London 40 The Royal Wedding 42 Cenotaph Cadets Parade and Service at Westminster St George -

Welsh Guards Magazine 2020

105 years ~ 1915 - 2020 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 WELSH GUARDS WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 MAGAZINE REGIMENTAL Cymru Am Byth Welsh Guards Magazine 2020_COVER_v3.indd 1 24/11/2020 14:03 Back Cover: Lance Sergeant Prothero from 1st Battalion Welsh Guards, carrying out a COVID-19 test, at testing site in Chessington, Kingston-upon-Thames. 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 1. Gdsm Wilkinson being 7 promoted to LCpl. 2. Gdsm Griffiths being promoted to LCpl. 3. LSgt Sanderson RLC being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. 4. Sgt Edwards being promoted to CSgt. 5. Gdsm Davies being promoted to LCpl. 6. Gdsm Evans 16 being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. 7. LSgt Bilkey, 3 Coy Recce, being promoted to Sgt 8. LSgt Jones, 3 Coy Snipers, being promoted to Sgt 9 9. Sgt Simons being awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. Front Cover: 1st Battalion Welsh Guards Birthday Tribute to 10. LSgt Lucas, 2 Coy being Her Majesty The Queen, Windsor Castle, Saturday 13th June 2020 10 promoted to Sgt Welsh Guards Magazine 2020_COVER_v3.indd 2 24/11/2020 14:04 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2020 COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Her Majesty The Queen COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales KG KT GCB OM AK QSO PC ADC REGIMENTAL LIEUTENANT COLONEL Major General R J Æ Stanford MBE REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Colonel T C S Bonas BA ASSISTANT REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Major M E Browne BEM REGIMENTAL VETERANS OFFICER Jiffy Myers MBE ★ REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London SW1E 6HQ Contact Regimental Headquarters by Email: [email protected] View the Regimental Website at: www.army.mod.uk/welshguards View the Welsh Guards Charity Website at: www.welshguardscharity.co.uk Contact the Regimental Veterans Officer at: [email protected] ★ AFFILIATIONS HMS Prince of Wales 5th Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment Régiment de marche du Tchad ©Crown Copyright: This publication contains official information. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

MILITARY POLICE, an Official U.S

USAMPS / MANSCEN This medium is approved for the official dissemination 573-XXX-XXXX / DSN 676-XXXX of material designed to keep individuals within the Army COMMANDANT knowledgeable of current and emerging developments within BG Stephen J. Curry .................................................... 563-8019 their areas of expertise for the purpose of enhancing their <[email protected]> professional development. ACTING ASSISTANT COMMANDANT By Order of the Secretary of the Army: COL Charles E. Bruce .................................................. 563-8017 PETER J. SCHOOMAKER <[email protected]> General, United States Army COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR Chief of Staff CSM James F. Barrett .................................................. 563-8018 Official: <[email protected]> DEPUTY ASSISTANT COMMANDANT—USAR COL Charles E. Bruce .................................................. 563-8082 JOEL B. HUDSON <[email protected]> Administrative Assistant to the DEPUTY ASSISTANT COMMANDANT—ARNG Secretary of the Army LTC Starrleen J. Heinen .................................. 596-0131, 38103 02313130330807 <[email protected]> DIRECTOR of TRAINING DEVELOPMENT MILITARY POLICE, an official U.S. Army professional COL Edward J. Sannwaldt, Jr........................................ 563-4111 bulletin for the Military Police Corps Regiment, contains infor- <[email protected]> mation about military police functions in maneuver and DIRECTORATE of COMBAT DEVELOPMENTS mobility operations, area security operations, internment/ MP DIVISION CHIEF -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-09-2 Volume 35 Number 2 April - June 2009

MIPB April - June 2009 PB 34-O9-2 Operations in OEF Afghanistan FROM THE EDITOR In this issue, three articles offer perspectives on operations in Afghanistan. Captain Nenchek dis- cusses the philosophy of the evolving insurgent “syndicates,” who are working together to resist the changes and ideas the Coalition Forces bring to Afghanistan. Captain Beall relates his experiences in employing Human Intelligence Collection Teams at the company level in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson provides a look into the balancing act U.S. Army chaplains as non-com- batants in Afghanistan are involved in with regards to Information Operations. Colonel Reyes discusses his experiences as the MNF-I C2 CIOC Chief, detailing the problems and solutions to streamlining the intelligence effort. First Lieutenant Winwood relates her experiences in integrating intelligence support into psychological operations. From a doctrinal standpoint, Lieutenant Colonels McDonough and Conway review the evolution of priority intelligence requirements from a combined operations/intelligence view. Mr. Jack Kem dis- cusses the constructs of assessment during operations–measures of effectiveness and measures of per- formance, common discussion threads in several articles in this issue. George Van Otten sheds light on a little known issue on our southern border, that of the illegal im- migration and smuggling activities which use the Tohono O’odham Reservation as a corridor and offers some solutions for combined agency involvement and training to stem the flow. Included in this issue is nomination information for the CSM Doug Russell Award as well as a biogra- phy of the 2009 winner. Our website is at https://icon.army.mil/ If your unit or agency would like to receive MIPB at no cost, please email [email protected] and include a physical address and quantity desired or call the Editor at 520.5358.0956/DSN 879.0956. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 105 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 144 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 1998 No. 11 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. Mr. GIBBONS. Mr. Speaker, I object Herger Markey Redmond The Reverend Ronald F. Christian, Hill Martinez Regula to the vote on the ground that a Hinojosa Mascara Reyes Director, Lutheran Social Services of quorum is not present and make the Hobson Matsui Riley Fairfax, VA, offered the following pray- point of order that a quorum is not Hoekstra McCarthy (MO) Rivers er: present. Holden McCarthy (NY) Rodriguez Almighty God, Your glory is made Hooley McCollum Roemer The SPEAKER. Evidently a quorum Horn McCrery Rogan known in the heavens, and the fir- is not present. Hostettler McGovern Rogers mament declares Your handiwork. The Sergeant at Arms will notify ab- Houghton McHale Rohrabacher Hoyer McHugh Ros-Lehtinen With the signs of Your creative good- sent Members. ness all about us, we must acknowledge Hulshof McInnis Rothman The vote was taken by electronic de- Hutchinson McIntosh Roukema Your presence in our world, through vice, and there wereÐyeas 353, nays 43, Inglis McIntyre Roybal-Allard Your people, and within us all. answered ``present'' 1, not voting 33, as Istook McKeon Royce So, therefore, we pray for Your Jackson (IL) McKinney Ryun follows: mercy when our ways are stubborn or Jackson-Lee Meehan Sabo [Roll No. 14] (TX) Meek (FL) Salmon uncompromising and not at all akin to Jefferson Meeks (NY) Sanchez Your desires. -

The Response to Hurricane Katrina: a Study of the Coast Guard's Culture, Organizational Design & Leadership in Crisis

The Response to Hurricane Katrina: A Study of the Coast Guard's Culture, Organizational Design & Leadership in Crisis By Gregory J. Sanial B.S. Marine Engineering, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, 1988 M.B.A. Business Administration, Pennsylvania State University, 1997 M.A. National Security & Strategic Studies, U.S. Naval War College, 2002 Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY at the JUL 0 2 2007 Massachusetts Institute of Technology L 2007 LIBRARIES June 2007 © Gregory J.Sanial. All rights reserved. ARCHIVES The author herby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: " , MIT Sloan School of Management May 11, 2007 Certified by: John Van Maanen Erwin H. Schell Professor of Organizational Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Z, /, ,.- V •. Stephen J. Sacca Director, MIT Sloan Fellows Program in Innovation and Global Leadership The Response to Hurricane Katrina: A Study of the Coast Guard's Culture, Organizational Design & Leadership in Crisis By Gregory J. Sanial Submitted to the M IT Sloan School of Management on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management ABSTRACT Hurricane Katrina slammed into the United States Gulf Coast early on August 28, 2005 killing almost 2,000 people and causing $81 billion in damages making Katrina the costliest natural disaster in United States history. The sheer magnitude of the devastation and destruction in New Orleans and the surrounding area remains incomprehensible to many disaster planners. -

Legal Impediments to Service: Women in the Military and the Rule of Law

08__MURNANE.DOC 6/18/2007 3:03 PM LEGAL IMPEDIMENTS TO SERVICE: WOMEN IN THE MILITARY AND THE RULE OF LAW LINDA STRITE MURNANE* PREAMBLE Since our nation’s birth, women have been engaged in the national defense in various ways. This article will examine the legal impediments to service by women in the United States military. This brings to light an interesting assessment of the meaning of the term “Rule of Law,” as the legal exclusions barring women from service, establishing barriers to equality and creating a type of legal glass ceiling to preclude promotion, all fell within the then-existing Rule of Law in the United States. Finally, this article looks at the remaining barriers to women in the military and reasons to open all fields and all opportunities to women in today’s military. I. THE CONCEPT OF THE RULE OF LAW Albert Venn Dicey, in “Law of the Constitution,” identified three principles which establish the Rule of Law: (1) the absolute supremacy or predominance of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power; (2) equality before the law or the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary courts; and (3) the law of the constitution is a consequence of the rights of individuals as defined and enforced by the courts.1 This concept of the Rule of Law has existed since the beginning of the nation, most famously reflected in the writings of John Adams in drafting the * Colonel, USAF, Ret. The author acknowledges with gratitude the research assistance of Vega Iodice, intern at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and lawyer apprentice at the Iodice Law Firm in Naples, Italy, in the preparation of this article. -

Generals: July 2018

GENERALS: JULY 2018 September 2014: General Sir Nicholas P. Carter(late Rifles): Chief of the Defence Staff, June 2018 (2/1959; 59) April 2016: General Sir Christopher M. Deverell(late Royal Tank Regiment): Commander, Joint Forces Command, April 2016 (1960; 58) March 2017: General Sir James R. Everard (late Royal Lancers): Deputy Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, March 2017 (9/1962; 55) June 2018: General Mark A.P. Carleton-Smith: Chief of the General Staff, June 2018 (2/1964; 54) LIEUTENANT-GENERALS: JULY 2018 July 2013: Lieutenant-General Sir John G. Lorimer(late Parachute Regiment): Defence Senior Advisor, Middle East, January 2018 (11/1962; 55) February 2014: Lieutenant-General Sir Mark W. Poffley(late Royal Logistic Corps): Deputy Chief of the Defence Staff (Military Capability), January 2016-January 2019; to retire, 2019 (1960; 58) June 2015: Lieutenant-General James I. Bashall (late Parachute Regiment) (4/1962; 56) July 2015: Lieutenant-General Timothy B. Radford (late Rifles): Commander, Allied Rapid Reaction Corps, July 2016 (2/1963; 55) December 2015: Lieutenant-General Nicholas A.W. Pope (late Royal Signals): Deputy Chief of the General Staff, December 2015 (7/1962; 56) March 2016: Lieutenant-General Paul W. Jaques (late Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers): Chief of Materiel (Land), March 2016 (5/1961; 57) April 2016: Lieutenant-General Richard E. Nugee (late Royal Artillery): Chief of Defence People, April 2016 (6/1963; 55) May 2016: Lieutenant-General Sir George P.R. Norton(late Grenadier Guards): U.K. Military Representative to NATO, May 2016 (11/1962; 55) December 2016: Lieutenant-General Patrick N.Y.M. Sanders(late Rifles): Commander, Field Army, December 2016 (4/1966; 52) April 2017: Lieutenant-General Richard F.P.