VICTOR HERBERT: ROMANTIC IDEALIST Edward N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

“I Am No Woman, I”: Gender, Sexuality, and Power in Elizabethan Erotic Verse

Volume 2 (2), 2009 ISSN 1756-8226 “I Am No Woman, I”: Gender, Sexuality, and Power in Elizabethan Erotic Verse CHLOE K PREEDY University of York Introduction: England’s “Female Prince” Elizabeth Tudor’s accession to the English throne in 1558 significantly challenged and disrupted contemporary assumptions about gender roles. Elizabeth I was an anointed monarch, but she was also a woman in a world of men. Early modern England was a patriarchal society in which the monarch’s control over the kingdom was often compared to a father’s power over his household (Shuger, 1997), and virtually all the powerful figures at Elizabeth’s court were male, including the members of her Privy Council. The expectation was that the highest political position of all, that of England’s sovereign, should also be held by a man, and in contemporary writings on the institution of monarchy the ruler’s body is always imagined to be male. During Elizabeth I’s reign, however, tension was generated by the gap between rhetoric and reality; while the ideal royal body might be gendered male in political discourse, Elizabeth’s own physical body was undeniably female. Elizabeth I’s political androgyny – she was known at home and abroad as a “female Prince”, and Parliamentary statute declared her a “king” for political purposes (Jordan, 1990) – raised serious questions about the relationship between gender and power, questions which were discussed at length by early modern lawyers and political theorists (Axton, 1977). However, such issues also had an influence on Elizabethan literature. Elizabeth I often exploited her physical femininity as a political tool: for instance, she justified her decision not to marry by casting herself as the unobtainable lady familiar to Elizabethans from the Petrarchan sonnet tradition, 1 and encouraged her courtiers to compete for political favour by courting 1 Francesco Petrarch was a fourteenth-century Italian scholar and poet who wrote a series of sonnets ( Il Conzoniere ) addressed to an idealised, sexually unavailable mistress. -

The Red Mill Music by Victor Herbert Book and Lyrics by Henry Blossom

The Red Mill Music by Victor Herbert Book and Lyrics by Henry Blossom Performing version edited by James Cooper Cast of characters “Con” Kidder “Kid” Conner } Two Americans “doing” Europe Burgomaster Burgomaster of Katwyk-aan-Zee Franz Sheriff of Katwyk-aan-Zee Willem Keeper of The Red Mill Inn Capt Davis Van Damm In love with Gretchen Governor of Zealand Engaged to Gretchen Gretchen The Burgomaster’s daughter Bertha The Burgomaster’s sister Tina Barmaid at The Red Mill Inn, Willem’s daughter Hon. Dudley (pronounced “Fanshaw”) Solicitor from London touring Holland by Featherstonhaugh car with his daughters Countess de la Pere Touring Holland by car with her sons Giselle and Brigitte Dudley’s daughters Hans and Peter Countess’s sons or villagers Rose and Daisy Flower Girls Gaston Burgomaster’s servant Chorus of peasants, artists, burghers and other townspeople Time: 1906 Place: Katwyk-aan-Zee Act I: At the sign of The Red Mill Act II: The Burgomaster’s Mansion 1 Musical Numbers Overture 4 Act I 1. By the Side of the Mill 12 2. Mignonette (Tina and Girls) 27 3. You can Never Tell About a Woman (Burgomaster and Willem) 34 4. Whistle It (Con, Kid, Tina) 41 5. A Widow Has Ways (Bertha) 47 6. The Isle of Our Dreams (Davis and Gretchen) 51 7. The Streets of New York (Con and Kid and Chorus) 58 8. The Accident (Ensemble) 68 8b. When You’re Pretty and the World is Fair (Ensemble) 81 9. Finale I – Moonbeams (Gretchen, Davis and Chorus) 92 Act II 10. Gossip Chorus (Ensemble) 107 11. -

The Fortune Teller the OHIO LIGHT OPERA STEVEN BYESS STEVEN DAIGLE Conductor Artistic Director the Fortune Teller

VICTOR HERBERT The Fortune Teller THE OHIO LIGHT OPERA STEVEN BYESS STEVEN DAIGLE Conductor Artistic Director The Fortune Teller Music......................................Victor Herbert ENSEMBLE: Book and Lyrics......................Harry B. Smith Jacob Allen, Natalie Ballenger, Sarah Best, Lori Birrer, John Vocal Score Reconstruction........Adam Aceto Callison, Ashley Close, Christopher Cobbett, Mary Griffin, Anna-Lisa Hackett, Geoffrey Kannerberg, Andy Maughan, Ohio Light Opera Olivia Maughan, Evan McCormack, Geoffrey Penar, Will Perkins, Madeline Piscetta, Zachary Rusk, Mark Snyder, Raina Thorne, Artistic Director........................Steven Daigle Angela Vågenes, Joey Wilgenbusch. Conductor.................................Steven Byess Stage Director.......................Ted Christopher Sound Designer..........................Brian Rudell PROGRAM NOTES ...............................Michael D. Miller Choreographer.....................Carol Hageman Victor Herbert, acknowledged as Costume Designer.................Whitney Locher the Father of American Operetta, Scenic Designer...............................Erich Keil was born in Dublin in 1859, the Lighting Designer.....................Krystal Kennel grandson of Irish novelist-artist- Production Stage Manager...Katie Humphrey composer Samuel Lover. The family eventually moved to Stuttgart where CAST: Victor’s initial studies toward a Musette / Irma...........................Amy Maples career in medicine or law were soon Sandor...........................David Kelleher-Flight replaced -

Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ral)

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Historic Sheet Music Collection Greer Music Library 1913 That's An Irish Lullaby (Too-ra-loo-ra-loo-ral) James R. Shannon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/sheetmusic Recommended Citation Shannon, James R., "That's An Irish Lullaby (Too-ra-loo-ra-loo-ral)" (1913). Historic Sheet Music Collection. 1080. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/sheetmusic/1080 This Score is brought to you for free and open access by the Greer Music Library at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historic Sheet Music Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ~i TOO-RA-LOO-RA-LOO-RAL --·r>*--<1·-- l InCrctoc) In E~ Contralto (el, to e!, J{ or Baritone (lead) Soprano (g to a/,J 1---------~-~---+------='-------4 or Tenor PUBLISHED IN THE FOLLOWING ARRANGEMENTS Vocal Solo, C-E~-F-G ... ... each .;o Piano Solo (Gotham Classics No. 85) .50 Vocal Duet, ED-G . .... ... ... each .60 i Part Mixed (SAB) . I; 2 Part (SA or TB) . .15 4 Part Mixed (SA TB) . I 5 3 Part Treble (SSA) .. .15 . Accordion Solo (Bass Clef) . .;o 4 Part Treble (SSAA) .. .. ....... .16 Vocal Orchestration, F-C . ..... each .75 4 Part Male (TTBB) ............... .15 Dance Orchestration (Fox Trot) . .7 5 Band .... ......... .. ......... 1.00 WHEN PERFORMING THIS CO MPOSITION KINDLY G !VE ALL PROGRAM C -

Herbert's Songs: Designed for Classical Singers A

HERBERT’S SONGS: DESIGNED FOR CLASSICAL SINGERS A CREATIVE PROJECT PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF MUSIC BY LAURA R. KRELL DR. MEI ZHONG-ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY, 2012 Herbert’s Songs: Designed for Classical Singers Introduction Victor Herbert has undoubtedly provided America some of its greatest, most tender, romantic, invigorating, and challenging songs for soprano. Today, Herbert’s masterworks appear simultaneously in both Musical Theater Anthologies and Operatic Collections. Many students encounter questions as to performance practice: can these songs be sung as “musical theater,” with young, immature voices, or should they be studied by classical singers? Despite the pool of speculation swirling around this issue, there has not been any significant research on this particular topic. This study will detail the vocal abilities of Herbert’s most prolific sopranos (Alice Nielsen, Fritzi Scheff, and Emma Trentini), and identify compositional elements of three of Herbert’s most famous arias (“The Song of the Danube,” “Kiss Me Again,” and “Italian Street Song”), using historical data to demonstrate that each composition was tailored specifically for the versatility and profound vocal ability of each opera singer, and is poorly mishandled by those without proper classical training. The writer will offer observations from three amateur online recordings of “Art Is Calling For Me.” The writer will use the recordings to highlight specific pitfalls untrained singers may encounter while singing Herbert, such as maneuvering coloratura passages, breath control, singing large intervallic leaps, and the repeated use of the upper tessitura. -

Showstoppers! Soprano

LIGHT OPERA SHOWSTOPPERS – SHOWSTOPPERS! The list below is a guide to arias from the realm of light opera that are bound to get attention, as they require not only exquisite singing, but also provide opportunities for acting, so necessary in the HAROLD HAUGH LIGHT OPERA VOCAL COMPETITION. Some, although from serious works, are light in nature, and are included. The links below the title, go to performances on YouTube, so you can audition the song. An asterisk (*) indicates the Guild has the score in English. SOPRANO ENGLISH Poor Wand’ring One – Pirates of Penzance (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QRnwT2EYD8 The Hours Creep On Apace - HMS Pinafore (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGMnr7tPKKU The Moon and I – The Mikado (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EcNtTm5XEfY I Built Upon a Rock – Princess Ida (Gilbert and Sullivan)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF_MHyXPui8 I Live, I Breathe – Ages Ago (Gilbert and Clay)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-HalKwnNd8 Light As Thistledown – Rosina (Shield) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yrQ2boAb50 When William at Eve – Rosina (Shield) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Vc50GGV_SA I Dreamt I Dwelt In Marble Halls – Bohemian Girl (Balfe)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IoM1hYqpRSI At Last I’m Sovereign Here – The Rose Of Castile (Balfe)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hswFzeqY8PY Hark the Ech’ing Air – The Fairy Queen (Purcell)* http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NeQMxI1S84U VIENNESE Meine Lippen Sie Kussen So Heiss – Giuditta (Lehar) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_kaOYC_Fww -

Precious Nonsense

Precious Nonsense NEWSLETTER OF THE MIDWESTERN GILBERT AND SULLIVAN SOCIETY June 2001 -- Issue 63 Of course, you will understand that, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, I am bound to see that due economy is observed. There's nothing like a bargain. W ith the postal rate on letters weighing more than an ounce going up on July 1, it seemed like a good idea to try to get a "fat" newsletter out before the change. So here we are. Although we're lacking any play synopses this time around, we do have the answers to last year's Big Quiz, plenty of news of G&S productions, and some interesting insights from Arthur Robinson. So let's see how it goes. Oh, Members, How Say You, What is it You've Light Opera at (330) 263-2345 / www.wooster.edu/OHIOLIGHTOPERA/ . Or e-mail Done? [email protected]. And their address is The We were saddened and pleased to learn that MGS College of Wooster, Wooster, OH 44691. member and frequent G&S lead performer David Michaels is leaving the Chicago area for Seattle. Sad because he’s Although Light Opera Works isn't presenting any G&S going, and glad because he’ll be seeing more of his family this season, they do have an interesting program for youth, (and able to report on G&S activity in Washington State)! featuring, among other things, an opportunity to work on a Best wishes for his move and his future! production of The Pirates of Penzance. Their Musical Theater Summer Workshops (“for kids 8 to 18") this year By the way, someone asked what our membership include Annie (July 9-14, 2001), Pirates of Penzance (July statistics are, after the renewals were returned. -

1914 the Ascap Story 1964 to Page 27

FEBRUARY 29, 1964 SEVENTIETH YEAR 50 CENTS New Radio Study 7A^ I NEW YORK-Response Ratings, a new and unique continuing study measuring radio station and jockey effectiveness, will he 'r, launched in next week's issue. This comprehensive radio analysis- another exclusive Billboard feature-will he carried weekly. Three different markets will be profiled in each issue. It will kick off in the March 7 Billboard with a complete study of the New York, Nashville, and San Francisco markets. In subsequent weeks, the study will consider all key areas. This service has been hailed by broadcast The International Music -Record Newsweekly industry leaders as a major breakthrough in station and personality Radio -TV Programming Phono-Tape Merchandising Coin Machine Operating analysis. Beatles Business Booms But Blessings Mixed Beatles Bug BeatlesGross r z As They 17 Mil. Plus Paris Dealer, 31-4*- t 114 In 6 Months 150 Yrs. Old, Control Air NEW YORK - In the six By JACK MAHER six months prior to the peak of Keeps Pace NEW YORK - While a few their American success, Beatles manufacturers were congratu- records grossed $17,500,000 ac- Story on Page 51 lating the Beatles for infusing cording to EMI managing direc- new life and excitement into the tor John Wall. record business others were This figure, which does not quietly venting their spleen include the huge sales of Beatles against the British group. records ín the U. S., shows the At the nub of their blasphe- staggering impact the group has mies was the enormous amount had on the record industry t r 1.+ra. -

The Influence of Ovid's Metamorphoses and Marlowe's

The Influence of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Marlowe’s Hero and Leander upon Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis Most literary critics and historians of English Renaissance literature agree that the basic story of Shakespeare’s epic poem Venus and Adonis is drawn from Book Ten of Ovid’s first-century Latin narrative poem Metamorphoses, namely Arthur Golding’s 1567 translation of the text (a book which Shakespeare probably first read as a child). Ovid’s version of the legend of Venus and Adonis tells the story of Venus taking Adonis on as her first human lover. The two become romantic companions and hunting partners. The mortal Adonis wishes to hunt dangerous beasts, hence Venus attempts to dissuade him but Adonis ignores Venus and is killed by a bore he is hunting. Shakespeare reworks Ovid’s basic story into a poem that is nearly 2,000 lines in length. Shakespeare, however, does not merely adapt Ovid’s poem, but instead reworks Ovid’s basic story of Venus and Adonis into a far more complicated poem that explores the nature of love and sexual desire from a variety of different perspectives. Shakespeare, interestingly, repositions Venus as the pursuer of Adonis, who is far more interested in hunting than romantic relations. While the poem represents a radical thematic break from Ovid’s original poem, Shakespeare nevertheless adheres quite closely to Ovid’s own poetic style throughout the poem, as well as Ovid’s particular use of setting and general story-structuring. Some critics have argued that Shakespeare’s version of Venus is meant to mock the role of Venus in classical mythology, while others argue that Shakespeare presents Venus and Adonis as being more akin to mother and son than lovers, and that Venus functions as something of a sexually empowered subverter of standard Elizabethan gender and romantic relations. -

2016; Pub. 2018

2016 Volume 6 Volume Volume 6 2016 Volume 6 2016 EDITORS at Purdue University Fort Wayne at Mount St. Mary’s University Fort Wayne, Indiana Emmitsburg, Maryland M. L. Stapleton, Editor Sarah K. Scott, Associate Editor Cathleen M. Carosella, Managing Editor Jessica Neuenschwander, Pub. Assistant BOARD OF ADVISORS Hardin Aasand, Indiana University–Purdue University, Fort Wayne; David Bevington, University of Chicago; Douglas Bruster, University of Texas, Austin; Dympna Callaghan, Syracuse University; Patrick Cheney, Pennsylvania State University; Sara Deats, University of South Florida; J. A. Downie, Goldsmiths College, University of London; Lisa M. Hopkins, Sheffield Hallam University; Heather James, University of Southern California; Roslyn L. Knutson, University of Arkansas, Little Rock; Robert A. Logan, University of Hartford; Ruth Lunney, University of Newcastle (Australia); Laurie Maguire, Magdalen College, Oxford University; Lawrence Manley, Yale University; Kirk Melnikoff, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; Paul Menzer, Mary Baldwin College; John Parker, University of Virginia; Eric Rasmussen, University of Nevada, Reno; David Riggs, Stanford University; John P. Rumrich, University of Texas, Austin; Carol Chillington Rutter, University of Warwick; Paul Werstine, King’s College, University of Western Ontario; Charles Whitney, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Marlowe Studies: An Annual is a journal devoted to studying Christopher Marlowe and his role in the literary culture of his time, including but not limited to studies of his plays and poetry; their sources; relations to genre; lines of influence; classical, medieval, and continental contexts; perfor- mance and theater history; textual studies; the author’s professional milieu and place in early modern English poetry, drama, and culture. From its inception through the current 2016 issue, Marlowe Studies was published at Purdue University Fort Wayne in Indiana. -

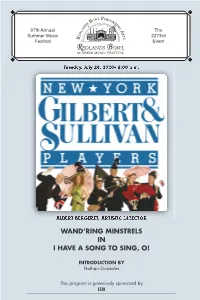

Wand'ring Minstrels in I Have a Song to Sing, O!

E OWL P RFO B RM S I D N N G A A L D R 97th Annual T The E S Summer Music R 2273rd Festival Event Tuesday, July 28, 2020 8:00 p.m. ● ALBERT BERGERET, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WAND’RING MINSTRELS IN I HAVE A SONG TO SING, O! INTRODUCTION BY Nathan Gonzales ________________________________________________________________________________ This program is generously sponsored by ______________________________________E_S__R_I ______________________________________ THIS EVENING’S ARTIST Director: James Mills Music Director & Conductor: Albert Bergeret Executive Producer: David Wannen Editor: Danny Bristoll Sarah Caldwell Smith, Soprano Rebecca Hargrove, Soprano Angela Christine Smith, Contralto Alex Corson, Tenor James Mills, Comic Baritone Matthew Wages, Bass-Baritone David Wannen, Bass Accompanist: Elizabeth Rogers MUSICAL NUMBERS With Cat-like Tread, Upon Our Prey We Steal (The Pirates of Penzance) . .Ensemble I Have a Song to Sing, O! (The Yeomen of the Guard) . .James Mills Sarah Caldwell Smith Am I Alone and Unobserved? (Patience) . .James Mills A British Tar (H.M.S. Pinafore) . .Alex Corson Matthew Wages David Wannen I’m Called Little Buttercup (H.M.S. Pinafore) . .Angela Christine Smith We’re Called Gondolieri (The Gondoliers) . .Alex Corson Matthew Wages Take a Pair of Sparkling Eyes (The Gondoliers) . .Alex Corson Oh, Better Far to Live and Die (The Pirates of Penzance) . .Matthew Wages and Men When All Night Long a Chap Remains (Iolanthe) . .David Wannen Three Little Maids From School are We (The Mikado) . .Rebecca Hargrove Angela Christine Smith Sarah Caldwell Smith The Sun, Whose Rays are All Ablaze (The Mikado) . .Rebecca Hargrove Here’s a How-de-do! (The Mikado) . .Alex Corson James Mills Rebecca Hargrove Alone, and Yet Alive! (The Mikado) .