'Underwriting': a Script Development Technique in the Age Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language of Darkness

ARTS-UG 1611 | FALL 2018 CLASS : TUESDAYS + THURSDAYS, 6:20 PM - 9:00 PM 194 MERCER STREET, ROOM 208 instructor Pedro Cristiani 1 Washington Pl, Room 431 (212) 992.7772 office hours : Wednesdays, 3:00 - 4:30 PM [email protected] “Horror is a reaction— it’s not a genre.” — John Carpenter course description From Murnau’s Nosferatu to Bryan Fuller’s Hannibal, horror has proven to spawn its own storytelling archetypes, serving as strong subtext for race, faith, politics and sexuality. This seven week arts workshop gives the participants the screenwriter’s tools and weapons to research, develop and execute an original genre feature outline. We will explore how different horror auteurs deliver a unique vision from the same source material, as well as how this particular genre has transcended and influenced even the most “respected” mainstream directors. The sessions will not only cover the question of subverting narrative components and theme, but also creating “mood” and the “sense of the ominous”. Students will research and settle on an original horror source [literary, folkloric or real-life], and will be guided throughout the stages of creating their own unique mythology, as part of the fully- developed feature outline— which will then generate a short film script in proper industry- standard format. In-class screening excerpts will include Dracula [Todd Browning and F. F. Coppola], The Thing [John Carpenter], Ringu [Hideo Nakata], Get Out [Jordan Peele], Let The Right One In [Tomas Alfredson], Rosemary’s Baby [Roman Polanski], The Fly [David Cronenberg], American Psycho [Mary Harron], Ju-On [Takashi Shimizu], The Shining [Stanley Kubrick], The Autopsy of Jane Doe [André Øvredal]. -

Story Documents Drama 2018

July 2018 | www.screenaustralia.gov.au Info Guide STORY DOCUMENTS STORY DOCUMENTS – DRAMA CONTENTS Introduction Core Concept Synopses Outline Treatment Scriptment Bible Scene Breakdown Introduction There are numerous types of short documents that shape a screen production - Synopses, Treatments, Outlines, Bibles; all means of succinctly communicating your story and ideas outside of just the screenplay. Very often we see these documents as a means of ‘selling’ the idea to networks, financiers, producers, or funding bodies. But the truth is that these documents are a vital part of the development process, not just an end result. Great ideas are not born – they are tested and crafted. For funding applications to Screen Australia applicants are required to provide a range of documents that best reflect the project and the intention of the creators. But importantly these documents are tools to incrementally improve and refine an idea, to identify its strengths and highlight its challenges. Many projects have stagnated or failed because of a flawed concept or weak story, which no amount of drafting can fix. Good short documents can make the process of defining your core concept and strengthening the story around it much more effective. That said, there can be a great deal of variation and debate about what is meant by terms such as Treatment, Bible, Scriptment, Outline, Scene Breakdown, and Synopsis, so this document is designed to help define some of these terms, offer practical advice and examples for writing them, and serve as a guide for how to better prepare your application. The modern screen industry is one of diverse platforms and formats. -

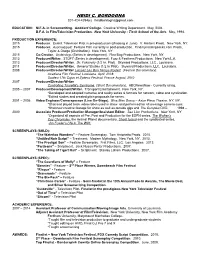

HEIDI C. BORDOGNA 201-424-4294(C) [email protected]

HEIDI C. BORDOGNA 201-424-4294(c) [email protected] EDUCATION: M.F.A. in Screenwriting. Goddard College. Creative Writing Department. May, 2004. B.F.A. in Film/Television Production. New York University - Tisch School of the Arts. May, 1994. PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE: 2015 Producer. Exiled. Television Pilot in pre-production (shooting in June). V. Herbert Prods. New York, NY. 2015 Producer. Asockalypse! Feature Film currently in post-production. Findmymissingsocks.com Prods., Taylor & Dodge (Distribution). New York, NY. 2015 Co-Creator. Underdogs (Series in development). Flea Bag Productions. New York, NY. 2013 Producer/Writer. STUFT (Series in development). Fuzz & Feathers Productions. New York/L.A. 2013 Producer/Director/Writer. Dr. Fukovsky (1/2 hr. Pilot). Skyward Productions, LLC., Louisiana. 2011 Producer/Director/Writer. General Studies (1/2 hr Pilot). Skyward Productions, LLC. Louisiana. 2008 Producer/Director/Writer Laissez Les Bon Temps Rouler! (Feature Documentary). Acadiana Film Festival, Louisiana, April, 2008. Saulieu 17th Cajun et Zydeco Festival, France August, 2010 2007 Producer/Director/Writer Controlling Tourette's Syndrome, (Short Documentary). ABCNewsNow - Currently airing. 2005 – 2007 Producer/Development/Writer. Transport Entertainment. New York, NY. *Developed and adapted narrative and reality series & formats for network, cable and syndication. *Edited sizzles and created pitch proposals for series. 2001 – 2006 Video Engineer/Cameraperson (Live On-Stage). Blue Man Group – Astor Place Theatre, NY, NY. *Shot and played back video roll-in used in show and performed for all on-stage camera cues. *Shot new creative footage for show as well as outside gigs and The Complex DVD. 1998 – 2000 Associate Producer/Production Manager/Assistant Editor. Sea Lion Productions. -

Hollywood Counterterrorism: Violence, Protest and the Middle East in U.S

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Hollywood Counterterrorism: Violence, Protest and the Middle East in U.S. Action Feature Films Jason Grant McKahan Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES HOLLYWOOD COUNTERTERRORISM: VIOLENCE, PROTEST AND THE MIDDLE EAST IN U.S. ACTION FEATURE FILMS By JASON GRANT MCKAHAN A Dissertation submitted to the College of Communication and Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2009 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Jason Grant McKahan defended on October 30, 2009. ____________________________________ Andrew Opel Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Cecil Greek University Representative ____________________________________ Donna Nudd Committee Member ____________________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________________ Stephen McDowell, Director, School of Communication ____________________________________________ Lawrence Dennis, Dean, College of Communication and Information The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this to my mother and father, who supported me with love and encouragement. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express thanks to Dr. Andy Opel, my committee chair. Since I first stepped into his office in 2003, Andy inspired me with his rebellious free thinking and encouraged me to see the deeper connections between things too often taken in isolation. Together, Andy and I daily observed an absurd world with deteriorating human rights and environmental catastrophe and sought to expose injustice and counter arrogance with resistant voices and compassionate values. -

Parts Development — the First Stage in Which the Ideas for the Film Are Created, Rights to Books/Plays Are Bought Etc., and Th

Parts Development — The first stage in which the ideas for the film are created, rights to books/plays are bought etc., and the screenplay is written. Financing for the project has to be sought and greenlit. Pre-production—Preparations are made for the shoot, in which cast and film crew are hired, locations are selected, and sets are built. Production—The raw elements for the film are recorded during the film shoot. Post-Production—The images, sound, and visual effects of the recorded film are edited. Distribution—The finished film is distributed and screened in cinemas and/or released on DVD. Development In this stage, the project's producer selects a story, which may come from a book or a play or another film or a true story or an original idea, etc. After identifying a theme or underlying message, the producer works with writers to prepare a synopsis. Next they produce a step outline, which breaks the story down into one-paragraph scenes that concentrate on dramatic structure. Then, they prepare a treatment, a 25-to-30-page description of the story, its mood, and characters. This usually has little dialogue and stage direction, but often contains drawings that help visualize key points. Another way is to produce a scriptment once a synopsis is produced. Next, a screenwriter writes a screenplay over a period of several months. The screenwriter may rewrite it several times to improve dramatization, clarity, structure, characters, dialogue, and overall style. However, producers often skip the previous steps and develop submitted screenplays which investors, studios, and other interested parties assess through a process called script coverage. -

Download 3Rd Semester Syllabus

ASSAM SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY Guwahati Course Structure and Syllabus MULTIMEDIA COMMUNICATION AND DESIGN (MCD) SEMESTER III / MCD /B.DES. (BACHELOR OF DESIGN) SL.NO. COURSE CODE COURSE TITLE L T P C THEORY/TUTORIAL/PRACTICAL 1 BMD 171301 World of Images and Objects 3 0 2 4 History of Art and 2 BMD 171302 3 0 0 3 Appreciation Fundamentals of Animation 3 BMD 171303 2 0 4 4 Design Concept of Storyboarding 4 BMD 171304 2 0 4 4 and Script Writing 5 BMD 171305 Concept of Film Making 2 0 4 4 6 BMD 171316 Design Studio - III 0 0 8 4 TOTAL 12 0 22 23 Total Contact Hours : 34 Total Credit : 23 Page 1 of 7 Course Title: WORLD OF IMAGES AND OBJECTS Class Hours/week 5 Course Code: BMD 171301 Expected weeks 12 L-T-P-C: 3-0-2-4 Total hrs. of 60 classes MODULE TOPIC COURSE CONTENT HOURS 1. Understanding of images 2. Study of types of images, meaning/expression of images. 3. Colour representation in images. 4. Object types – 2D/3D figure study, form 1 UNIT - 1 24 study etc. 5. Understanding shape, form, colour in objects. 6. Brief history on Art, Images and Objects. 1. Study of photograph, painting, sketch etc. 2. Experimenting with images and objects 2 UNIT - 2 36 – photographic image, objects. 3. Images and objects in digital and virtual world. TOTAL 60 TEXTBOOKS / REFERENCES: 1. The Designed World: Images, Objects, Environments- By Richard Buchanan (Editor), Dennis Doordan (Editor), Victor Margolin (Editor), ISBN-13: 978-1847885852, ISBN-10: 1847885853. -

The Screen Novel: a Creative Practice Approach to Developing a Screen Idea for the Television Crime Thriller

THE SCREEN NOVEL: A CREATIVE PRACTICE APPROACH TO DEVELOPING A SCREEN IDEA FOR THE TELEVISION CRIME THRILLER A project submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Sculley Bachelor of Media and Communication (Honours) RMIT University School of Media and Communication College of Design and Social Context RMIT University October 2017 DECLARATION I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. I also acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Stephen Sculley October 2017 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my supervisors, Associate Professor Craig Batty and Dr Stephen Gaunson, who steered and guided me through this PhD. Their knowledge, support and professionalism enabled me to remain focused and energised throughout the course of the research. I also thank all members of the review panels who provided feedback and support during the course of this research. I am additionally indebted to staff at the AFI Research Collection who assisted me in the early stages of my research and to the broader community of RMIT University. Finally, thanks to friends and family, in particular Paul Weedon, Jandy Paramanathan, George Kovevic and Mark Lane, who were supportive and interested in my development and process of discovery. -

Story Documents

January 2016 | www.screenaustralia.gov.au Info Guide STORY DOCUMENTS STORY DOCUMENTS – DRAMA Contents Core Concept ..................................................................................................................... 2 Synopses ............................................................................................................................. 4 One-sentence synopsis or logline ........................................................................................................... 4 One-paragraph synopsis .......................................................................................................................... 4 Pitch version of the one-paragraph synopsis .............................................................................................. 5 One-page synopsis .................................................................................................................................. 5 Outline ................................................................................................................................. 7 Scene breakdown ............................................................................................................... 8 Treatment ........................................................................................................................ 9 Scriptment ......................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction Funding applicants are often required to provide short -

STRANGE DAYS Scriptment by James Cameron at the Beginning Of

STRANGE DAYS Scriptment by James Cameron At the beginning of any writing project is the agonizing period in which nebulous ideas dance before the mind's eye like memories of a dream, and vaporous vague shapes take on human form and begin to answer to their names. Trying to will a world into existence. I circle around it, nibbling at the edges, writing notes about the social infrastructure and expounding to no one in particular about the themes of the thing. Then slowly a change happens. Without warning, it becomes easier to write a scene than to write notes about the scene. I start sticking words in the mouths of characters who are still mannequins, forcing them to move and to walk. Slowly their movements become more human. The curve inflects upward, the pace increases. The characters begin to say things in their own words. By the end of this period I'm writing ten pages a day. The last day becomes endless, often stretching round the clock to the following noon. The curve becomes almost vertical as the thing seems to come alive. I become a witness only, a court reporter getting it down as fast as I can. Lenny Nero was born in 1985 when I decided to write a film noir thriller taking place on New Year's Eve 1999. I was fascinated by the dramatic and thematic potentials of the millennium, and the idea of doomsday as a backdrop for the redemption of one individual. At that time I made a few notes, totaling less than five handwritten pages. -

Video Production(207) Unit -1

VIDEO PRODUCTION(207) UNIT -1 Introduction to Video Production Video production is the process of creating video by capturing moving images (videography), and creating combinations and reductions of parts of this video in live production and post- production (video editing). In most cases the captured video will be recorded on electronic media such as video tape, hard disk, or solid state storage, but it might only be distributed electronically without being recorded. It is the equivalent of filmmaking, but with images recorded electronically instead of film stock. Practically, video production is the art and service of creating content and delivering a finished video product. This can include production of television programs, television commercials, corporate videos, event videos, wedding videos and special-interest home videos. A video production can range in size from a family making home movies with a prosumer camcorder, a one solo camera operator with a professional video camera in a single-camera setup (aka a "one- man band"), a videographer with a sound person, to a multiple-camera setup shoot in a television studio to a production truck requiring a whole television crew for an electronic field production (EFP) with a production company with set construction on the backlot of a movie studio. Styles of shooting include on a tripod (aka "sticks")[1] for a locked-down shot; hand-held to attain a more jittery camera angle or looser shot, incorporating Dutch angle, Whip pan and whip zoom; on a jib that smoothly soars to varying heights; and with a Steadicam for smooth movement as the camera operator incorporates cinematic techniques moving through rooms, as seen in The Shining. -

FEATURE FILM VIRGIN © 2006 D F Mamea Inspired by a True Story

FEATURE FILM VIRGIN © 2006 D F Mamea Inspired by a true story. Script This is what I get for being impatient. After a couple of paid gigs - both in development hell - I wanted a credit. I was going to be one of those self-starters. I sounded out FRUSTRATED DIRECTOR, a fellow film school graduate, on my wildly ambitious idea: I would outline a feature-length story for a bunch of actors to workshop, he and the actors would hit the streets guerrilla-styles, and BAM! an indie feature. He loved it. (I could see it now: "Written by Impatient Screenwriter"; I had to talk Frustrated Director down from a "A film by" credit to "Directed by" though - whose insane idea was this to begin with, bub? Best to thrash these things out as early as possible.) Frustrated Director had the connections. The production company he worked for was suffocating his creativity but it had all the equipment and facilities that we would need. He also knew a couple of young 'n' hungry actors who were looking for just this kind of project. I drafted a twenty-page treatment that had all the clichés I abhorred. I didn't have the luxury of time. I discovered a newfound admiration for those B- to Z-movie screenwriters: that love-triangle between the protagonist, antagonist and the damsel - 's there for a reason, bud. Frustrated Director read it, adored it, but suggested that some 'indicative dialogue' be included so that the actors could really get into their characters. I drafted a fifty-page scriptment. -

Architecture As a Screenplay1

Z. Herbert, Znaki na papierze , Wydawnictwo BOSZ, R.U. Russin, W.M. Downs, Jak napisa 4 scenariusz Olszanica 2008. [ lmowy , Wydawnictwo Wojciech Marzec, Warszawa T. Mann, Józef i jego bracia , Czytelnik, Warszawa 2005. 1961. W. Tatarkiewicz, Dzieje sze Vciu poj B4 : sztuka, pi Bk- I. Montagu, With Eisenstein in Hollywood , Seven Seas no, forma, twórczo V4 , odtwórczo V4 , prze bycie estetyczne , Publishers, Berlin 1974. PWN, Warszawa 1976. H. Rauterberg, Talking Architecture. Interviews with J. Wójcik, Labirynt Vwiat a, opracowanie Seweryn Ku- architects , Prestel Verlag, Munich, London, New York Vmierczyk, Wydawnictwo CANONIA, Warszawa 2006. 2012. W.J. Robinson, The Form and Structure of Architec- Czes aw Bielecki, dr tural Knowledge: From Practice to Discipline , w: A. Pi- ul. auawskiego 2 otrowski, W.J. Robinson, The Discipline of Architecture , 02-641 Warszawa University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2001. tel.: +48 22 625 43 32 [email protected] ESSAYS ARCHITECTURE AS A SCREENPLAY 1 CZES AW BIELECKI “- So you proceed like a writer?” “- I listen to my inner ear and see what experiences I can call on to tackle a new (...) job. I often experience – as writers say – that the book writes itself. You make a start and then have to let go to fi nd out where the material is taking you. I fi nd it quite surprising how the images come up in my mind – sometimes it’s like in the cinema.” 2 Peter Zumthor Film people are keen on saying that a screenplay today we are reading the screenplays of Antonioni, is not something you write; it is something you Bergman, Kie Vlowski and Piesiewicz it is because constantly overwrite.