The Screen Novel: a Creative Practice Approach to Developing a Screen Idea for the Television Crime Thriller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCWC WAG Creative Writing

GASTON COLLEGE Creative Writing Writing Center I. GENERAL PURPOSE/AUDIENCE Creative writing may take many forms, such as fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, playwriting, and screenwriting. Creative writers can turn almost any situation into possible writing material. Creative writers have a lot of freedom to work with and can experiment with form in their work, but they should also be aware of common tropes and forms within their chosen style. For instance, short story writers should be aware of what represents common structures within that genre in published fiction and steer away from using the structures of TV shows or movies. Audiences may include any reader of the genre that the author chooses to use; therefore, authors should address potential audiences for their writing outside the classroom. What’s more, students should address a national audience of interested readers—not just familiar readers who will know about a particular location or situation (for example, college life). II. TYPES OF WRITING • Fiction (novels and short stories) • Creative non-fiction • Poetry • Plays • Screenplays Assignments will vary from instructor to instructor and class to class, but students in all Creative Writing classes are assigned writing exercises and will also provide peer critiques of their classmates’ work. In a university setting, instructors expect prose to be in the realistic, literary vein unless otherwise specified. III. TYPES OF EVIDENCE • Subjective: personal accounts and storytelling; invention • Objective: historical data, historical and cultural accuracy: Work set in any period of the past (or present) should reflect the facts, events, details, and culture of its time and place. -

The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic«

DOI 10.1515/jlt-2013-0006 JLT 2013; 7(1–2): 135–153 Ted Nannicelli The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic« Abstract: Are screenplays – or at least some screenplays – works of literature? Until relatively recently, very few theorists had addressed this question. Thanks to recent work by scholars such as Ian W. Macdonald, Steven Maras, and Steven Price, theorizing the nature of the screenplay is back on the agenda after years of neglect (albeit with a few important exceptions) by film studies and literary studies (Macdonald 2004; Maras 2009; Price 2010). What has emerged from this work, however, is a general acceptance that the screenplay is ontologically peculiar and, as a result, a divergence of opinion about whether or not it is the kind of thing that can be literature. Specifically, recent discussion about the nature of the screenplay has tended to emphasize its putative lack of ontological autonomy from the film, its supposed inherent incompleteness, or both (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48; Price 2010, 38–42). Moreover, these sorts of claims about the screenplay’s ontology – its essential nature – are often hitched to broader arguments. According to one such argument, a screenplay’s supposed ontological tie to the production of a film is said to vitiate the possibility of it being a work of literature in its own right (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48). According to another, the screenplay’s tenuous literary status is putatively explained by the idea that it is perpetually unfinished, akin to a Barthesian »writerly text« (Price 2010, 41). -

Why Does the Screenwriter Cross the Road…By Joe Gilford 1

WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 1 WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD? …and other screenwriting secrets. by Joe Gilford TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (included on this web page) 1. FILM IS NOT A VISUAL MEDIUM 2. SCREENPLAYS ARE NOT WRITTEN—THEY’RE BUILT 3. SO THERE’S THIS PERSON… 4. SUSTAINABLE SCREENWRITING 5. WHAT’S THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN?—THAT’S WHAT HAPPENS! 6. IF YOU DON’T BELIEVE THIS STORY—WHO WILL?? 7. TOOLBAG: THE TRICKS, GAGS & GADGETS OF THE TRADE 8. OK, GO WRITE YOUR SCRIPT 9. NOW WHAT? INTRODUCTION Let’s admit it: writing a good screenplay isn’t easy. Any seasoned professional, including me, can tell you that. You really want it to go well. You really want to do a good job. You want those involved — including yourself — to be very pleased. You really want it to be satisfying for all parties, in this case that means your characters and your audience. WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 2 I believe great care is always taken in writing the best screenplays. The story needs to be psychically and spiritually nutritious. This isn’t a one-night stand. This is something that needs to be meaningful, maybe even last a lifetime, which is difficult even under the best circumstances. Believe it or not, in the end, it needs to make sense in some way. Even if you don’t see yourself as some kind of “artist,” you can’t avoid it. You’re going to be writing this script using your whole psyche. -

The Gothic Novel and the Lingering Appeal of Romance

The Gothic Novel and the Lingering Appeal of Romance While the origins of most literary genres are lost, either in scholarly controversy or the dark backward and abysm of time, those of the Gothic novel present an admirable clarity. Beneath the papier-mâché machicolations of Strawberry Hill, the antiquarian and aesthete Horace Walpole, inspired by a nightmare involving ‘a giant hand in armour,’ created at white heat the tale published Christmas 1764 as The Castle of Otranto. Not one but two genres were thus begun. The one established first was the historical romance, which derived from elements in both Otranto and an earlier romance by Thomas Leland, Longsword, Earl of Salisbury (1762). This form was pioneered by William Hutchinson's The Hermitage (1772), and developed by Clara Reeve (in The Champion of Virtue, 1777, retitled 1778 The Old English Baron) and Sophia Lee in The Recess (1783B85); it reached something like canonical status with the medieval romances of Walter Scott. The second, the Gothic tale of supernatural terror, was slower to erupt. The Otranto seed has time to travel to Germany and bear fruit there in the Räuber- und Ritter-romane before being reengrafted onto its native English soil. It was not until the last decade of the eighteenth century that the Gothic became a major force in English fiction, so much so that tales set in Italian castles and Spanish monasteries began to crowd out those set in London houses and Hampshire mansions. The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), by Ann Radcliffe, and The Monk (1796), by Matthew G. Lewis, spawned numberless imitators in a craze whose original impetus carried it into the next century. -

The Power of Short Stories, Novellas and Novels in Today's World

International Journal of Language and Literature June 2016, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 21-35 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2015. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v4n1a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v4n1a3 The Power of Short Stories, Novellas and Novels in Today’s World Suhair Al Alami1 Abstract The current paper highlights the significant role literature can play within EFL contexts. Focusing mainly on short stories, novellas and novels, the paper seeks to discuss five points. These are: main elements of a short story/novella/novel, specifications of a short story/novella/novel-based course, points for instructors to consider whilst dealing with a short story/novella/novel within EFL contexts, recommended approaches which instructors may employ in the EFL classroom whilst discussing a short story/novella/novel, and language assessment of EFL learners using a short story/novella/novel-based course. Having discussed the aforementioned points, the current paper proceeds to present a number of recommendations for EFL teaching practitioners to consider. Keywords: Short Stories; Novellas; Novels Abbreviation: EFL (English as a Foreign Language) 1. Introduction In an increasingly demanding and competitive world, students need to embrace the four Cs: communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Best practices in the twenty-first century education, therefore, require practical tools that facilitate student engagement, develop life skills, and build upon a solid foundation of research whilst supporting higher-level thinking. With the four Cs in mind, the current paper highlights the significant role literature can play within EFL contexts. -

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto 1 The Sadleir-Black Collection 2 2 The Microfilm Collection 7 3 Gothic Origins 11 4 Gothic Revolutions 15 5 The Northanger Novels 20 6 Radcliffe and her Imitators 23 7 Lewis and her Followers 27 8 Terror and Horror Gothic 31 9 Gothic Echoes / Gothic Labyrinths 33 © Peter Otto and Adam Matthew Publications Ltd. Published in Gothic Fiction: A Guide, by Peter Otto, Marie Mulvey-Roberts and Alison Milbank, Marlborough, Wilt.: Adam Matthew Publications, 2003, pp. 11-57. Available from http://www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/gothic_fiction/Contents.aspx Deposited to the University of Melbourne ePrints Repository with permission of Adam Matthew Publications - http://eprints.unimelb.edu.au All rights reserved. Unauthorised Reproduction Prohibited. 1. The Sadleir-Black Collection It was not long before the lust for Gothic Romance took complete possession of me. Some instinct – for which I can only be thankful – told me not to stray into 'Sensibility', 'Pastoral', or 'Epistolary' novels of the period 1770-1820, but to stick to Gothic Novels and Tales of Terror. Michael Sadleir, XIX Century Fiction It seems appropriate that the Sadleir-Black collection of Gothic fictions, a genre peppered with illicit passions, should be described by its progenitor as the fruit of lust. Michael Sadleir (1888-1957), the person who cultivated this passion, was a noted bibliographer, book collector, publisher and creative writer. Educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford, Sadleir joined the office of the publishers Constable and Company in 1912, becoming Director in 1920. He published seven reasonably successful novels; important biographical studies of Trollope, Edward and Rosina Bulwer, and Lady Blessington; and a number of ground-breaking bibliographical works, most significantly Excursions in Victorian Bibliography (1922) and XIX Century Fiction (1951). -

2.3 Flash-Forward: the Future Is Now

2.3 Flash-Forward: The Future is Now BY PATRICIA PISTERS 1. The Death of the Image is Behind Us Starting with the observation that “a certain idea of fate and a certain idea of the image are tied up in the apocalyptic discourse of today’s cultural climate,” Jacques Rancière investigates the possibilities of “imageness,” or the future of the image that can be an alternative to the often-heard complaint in contemporary culture that there is nothing but images, and that therefore images are devoid of content or meaning (1). This discourse is particularly strong in discussions on the fate of cinema in the digital age, where it is commonly argued that the cinematographic image has died either because image culture has become saturated with interactive images, as Peter Greenaway argues on countless occasions, or because the digital has undermined the ontological photographic power of the image but that film has a virtual afterlife as either information or art (Rodowick 143). Looking for the artistic power of the image, Rancière offers in his own way an alternative to these claims of the “death of the image.” According to him, the end of the image is long behind us. It was announced in the modernist artistic discourses that took place between Symbolism and Constructivism between the 1880s and 1920s. Rancière argues that the modernist search for a pure image is now replaced by a kind of impure image regime typical for contemporary media culture. | 1 2.3 Flash-Forward: The Future is Now Rancière’s position is free from any technological determinism when he argues that there is no “mediatic” or “mediumistic” catastrophe (such as the loss of chemical imprinting at the arrival of the digital) that marks the end of the image (18). -

Writing Steps

PREWRITING ● gather your thoughts and ideas ○ read, research, interview, experience, discuss, reflect ○ brainstorm, list, journal, freewrite, cluster ● direct your writing ○ determine your purpose (what you want your paper to do) ○ focus and direct your ideas to address your purpose ○ topic, thesis, capsule summary ● tailor your writing ○ determine your audience ○ choose vocabulary, syntax, formality, appeal, organization, approach ○ capture essence and flavor of paper ● plan your writing ○ organize your ideas into an outline or plan ○ chronological, spatial, topical, priority ○ inductive (exploratory), deductive (argumentative) DRAFTING ● get situated ○ comfortable, stimulating, no distractions ● express your ideas without worrying about mechanical details ○ let thoughts flow ○ do not struggle with words, spelling, punctuation, other details ○ do not follow urge to reread, restructure, rewrite ○ write quickly, informally ○ concentrate on main ideas and message ● stick to subject ○ avoid digression into interesting examples ○ follow outline or plan (with minor modifications) ○ use transitions to connect and show relationships between and among ideas ● write draft in one sitting ○ consistent tone, smooth continuity ● consider writing a second, independent draft ○ compare the independent drafts and pull out best parts of each ● take a break when your draft is complete REVISING ● re-envision what you have written ○ ensure your paper fulfills its purpose (what you want the paper to do) ○ consider alternative ways to more effectively, efficiently -

Dirk Nel Director of Photography

Dirk Nel Director of Photography Credits include: GRACE Director: Henrik Georgsson Mystery Crime Drama Producer: Kiaran Murray-Smith Featuring: John Simm, Richie Campbell, Rakie Ayola Production Co: Second Act Productions / ITV REDEMPTION Director: John Hayes Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: John Wallace Featuring: Paula Malcomson, Abby Fitz, Thaddea Graham Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / Metropolitan Films Virgin Media One / ITV WHITSTABLE PEARL Director: David Caffrey Darkly Comic Crime Drama Series Producer: Guy Hescott Featuring: Kerry Godliman, Howard Charles, Frances Barber Production Co: Buccaneer Media / Acorn TV LIFE Directors: Iain Forsyth, Kate Hewitt, Jane Pollard Drama Producer: Kate Crowther Featuring: Alison Steadman, Adrian Lester, Victoria Hamilton Production Co: Drama Republic / BBC One MARCELLA Director: Ashley Pearce Crime Noir Thriller Producer: Elliott Swift Featuring: Anna Friel, Aaron McCusker, Hugo Speer Production Co: Buccaneer Media / Netflix / ITV ACKLEY BRIDGE Director: Rachna Suri Drama Producer: Jo Johnson Featuring: Jo Joyner, Liz White, Paul Nicholls Production Co: The Forge / Channel 4 VERA: COLD RIVER Director: Carolina Giammetta Crime Drama Producer: Will Nicholson Featuring: Brenda Blethyn, Paul Kaye, Kenny Doughty Production Co: ITV BLACK EARTH RISING Director: Hugo Blick Thriller Drama Series Producer: Abi Bach Eps 1, 6, 8 Featuring: John Goodman, Michaela Coel, Harriet Walter Production Co: Drama Republic / BBC Two Dirk Nel | Director of Photography 2 MAIGRET IN MONTMARTRE Director: Thaddeus -

ID Nr Titel Vorname Regisseur Name Regisseur Produzent Land Jahr

Länge Vorname Name Inv.for ID Nr Titel Produzent LandJahr Genre in über den Film Sonstiges Regisseur Regisseur mat min. 1469 838 -1250 Stephen Barcelo La fémis F 2002 Dokumentarfilm 13 2002 VHS + 838A 2303 1074 -1250 Stephen Barcelo La fémis F 2002 Dokumentarfilm 13 VHS 11. SaarLorLux Le Lierre, Ville de Dokumentation - Interviews mit: Jochen Senf. Barbara +Nr. 666A, 1186 666 Festival du film et de Thierry Léger F 2000 Dokumentation 10 VHS Thionville Zimmer, Pierre Smal, diversen Gästen. 666B, 666C la vidéo Nutzung der ereignislosen Zeit, "während der ereignislosen Zeit geschieht nichts", "eine Zeit der Untätigkeit". Dieses 11mi Video versucht durch eine plastische und sensible Nutzung 2170 1330 11'33 David Schumann Ecole de l'image d' Epinal F 2003 Experi'video miniDV n33 des Mediums das Gegenteil zu beweisen. Von unproduktiv zu unrentabel definiert sich die ereignislose Zeit auch durch ihr Sein und ihr graphisches Vokabular. Die "saynettes" (Einakter) sind Personenporträts. Man Sophie- nimmt reale Bilder, verändert sie und verwandelt sie in 2654 797 12 saynettes Gautier Sophie-Charlotte Gautier F 2001 Spielfilm 10 VHS Original DV Charlotte Geschichten. Kurze Szenen wie ein Augenblinzeln, so dass jeder seine eigene Geschichte erfinden kann. anderer Titel: Saarländisches Filmbüro, 12 mal 3; 12 x 3 Autoportraits - Selbstportraits von 12 Jugendliche aus Saarbrücken und 2791 1379 Jörg Kattenbeck Centre Social le Lierre D/F 2000 Dokumentarfilm 39 VHS anderer Titel: Selbstporträts Thionville von 12 bis 18 Jahren. Thionville 12 Auto- Portraits anderer Titel: Saarländisches Filmbüro, 12 mal 3; 12 x 3 Autoportraits - Selbstportraits von 12 Jugendliche aus Saarbrücken und 2790 1402 Jörg Kattenbeck Centre Social le Lierre D/F 2000 Dokumentarfilm 39 DV anderer Titel: Selbstporträts Thionville von 12 bis 18 Jahren. -

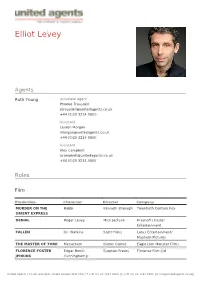

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

143 the Flashforward Facility at DESY Abstract 1. Introduction

DESY 15-143 The FLASHForward Facility at DESY A. Aschikhin1, C. Behrens1, S. Bohlen1, J. Dale1, N. Delbos2, L. di Lucchio1, E. Elsen1, J.-H. Erbe1, M. Felber1, B. Foster3,4,*, L. Goldberg1, J. Grebenyuk1, J.-N. Gruse1, B. Hidding3,5, Zhanghu Hu1, S. Karstensen1, A. Knetsch3, O. Kononenko1, V. Libov1, K. Ludwig1, A. R. Maier2, A. Martinez de la Ossa3, T. Mehrling1, C. A. J. Palmer1, F. Pannek1, L. Schaper1, H. Schlarb1, B. Schmidt1, S. Schreiber1, J.-P. Schwinkendorf1, H. Steel1,6, M. Streeter1, G. Tauscher1, V. Wacker1, S. Weichert1, S. Wunderlich1, J. Zemella1, J. Osterhoff1 1 Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), Notkestrasse 85, 22607 Hamburg, Germany 2 Center for Free-Electron Laser Science & Department of Physics, University of Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, 22761 Hamburg, Germany 3 Department of Physics, University of Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, 22761 Hamburg, Germany 4 also at DESY and University of Oxford, UK 5 also at University of Strathclyde, UK 6 also at University of Sydney, Australia * Corresponding author Abstract The FLASHForward project at DESY is a pioneering plasma-wakefield acceleration experiment that aims to produce, in a few centimetres of ionised hydrogen, beams with energy of order GeV that are of quality sufficient to be used in a free-electron laser. The plasma wave will be driven by high- current density electron beams from the FLASH linear accelerator and will explore both external and internal witness-beam injection techniques. The plasma is created by ionising a gas in a gas cell with a multi-TW laser system, which can also be used to provide optical diagnostics of the plasma and electron beams due to the <30 fs synchronisation between the laser and the driving electron beam.