Etiology and Aggravation in Thoracic Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management, Avoiding Surgical Lung Biopsy

395 Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management, Avoiding Surgical Lung Biopsy Ferran Morell, MD1,2 Ana Villar, MD2,3 Iñigo Ojanguren, MD2,3 Xavier Muñoz, MD2,3 María-Jesús Cruz, PhD2,3 1 Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca (VHIR), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain Address for correspondence Ferran Morell, MD, Vall d’Hebron Institut 2 Ciber de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES), Barcelona, Spain de Recerca (VHIR), PasseigValld’Hebron, 119-129, 08035 Barcelona, 3 Servei de Pneumologia, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Catalonia, Spain (e-mail: [email protected]). Barcelona, Spain Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016;37:395–405. Abstract This review presents an update of the currently available information related to Keywords hypersensitivity pneumonitis, with a particular focus on the contribution of several ► hypersensitivity techniques in the diagnosis of this condition. The methods discussed include proper pneumonitis elaboration of a complete medical history, targeted auscultation, detection of specific ► bronchoalveolar immunoglobulin G antibodies against the most common antigens causing this disease, lavage skin tests, antigen-specific lymphocyte activation assays, bronchoalveolar lavage, and ► fi speci c inhalation cryobiopsy. Special emphasis is placed on the relevant contribution of specificinhalation challenge challenge (bronchial challenge test). Surgical lung biopsy is presented as the ultimate ► bronchial challenge recourse, to be used when the diagnosis cannot be reached through the other methods test covered. -

Workers' Compensation for Occupational Respiratory Diseases

ORIGINAL ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.S.S47 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: S47-51 Workers’ Compensation for Occupational Respiratory Diseases So-young Park,1 Hyoung-Ryoul Kim,2 The respiratory system is one of the most important body systems particularly from the and Jaechul Song3 viewpoint of occupational medicine because it is the major route of occupational exposure. In 2013, there were significant changes in the specific criteria for the recognition of 1Occupational Lung Diseases Institute, Korea Workers’ Compensation & Welfare Service, Ansan; occupational diseases, which were established by the Enforcement Decree of the Industrial 2Department of Occupational and Environmental Accident Compensation Insurance Act (IACIA). In this article, the authors deal with the Medicine, College of Medicine, the Catholic former criteria, implications of the revision, and changes in the specific criteria in Korea by University of Korea, Seoul; 3Department of focusing on the 2013 amendment to the IACIA. Before the 2013 amendment to the IACIA, Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, occupational respiratory disease was not a category because the previous criteria were Korea based on specific hazardous agents and their health effects. Workers as well as clinicians were not familiar with the agent-based criteria. To improve these criteria, a system-based Received: 20 December 2013 structure was added. Through these changes, in the current criteria, 33 types of agents Accepted: 6 April 2014 and 11 types of respiratory diseases are listed under diseases of the respiratory system. In Address for Correspondence: the current criteria, there are no concrete guidelines for evaluating work-relatedness, such Hyoung-Ryoul Kim, MD as estimating the exposure level, latent period, and detailed examination methods. -

Silicosis: Pathogenesis and Changklan Muang Chiang Mai 50100 Thailand; Tel: 66 53 276364; Fax: 66 53 273590; E-Mail

Central Annals of Clinical Pathology Bringing Excellence in Open Access Review Article *Corresponding author Attapon Cheepsattayakorn, 10th Zonal Tuberculosis and Chest Disease Center, 143 Sridornchai Road Silicosis: Pathogenesis and Changklan Muang Chiang Mai 50100 Thailand; Tel: 66 53 276364; Fax: 66 53 273590; E-mail: Biomarkers Submitted: 04 October 2018 Accepted: 31 October 2018 1,2 3 Attapon Cheepsattayakorn * and Ruangrong Cheepsattayakorn Published: 31 October 2018 1 10 Zonal Tuberculosis and Chest Disease Center, Chiang Mai, Thailand ISSN: 2373-9282 2 Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand Copyright 3 Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand © 2018 Cheepsattayakorn et al. OPEN ACCESS Abstract Ramazzini first described this disease, namely “Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanokoniosis” Keywords and then was changed according to the types of exposed dust. No reliable figures on the silica- • Silicosis inhalation exposed individuals are officially documented. How silica particles stimulate pulmonary • Biomarkers response and the exact path physiology of silicosis are still not known and urgently require further • Pathogenesis research. Nevertheless, many researchers hypothesized that pulmonary alveolar macrophages play a major role by secreting fibroblast-stimulating factor and re-ingesting these ingested silica particles by the pulmonary alveolar macrophage with progressive magnification. Finally, ending up of the death of the pulmonary alveolar macrophages and the development of pulmonary fibrosis appear. Various mediators, such as CTGF, FBRS, FGF2/bFGF, and TNFα play a major role in the development of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. A hypothesis of silicosis-associated abnormal immunoglobulins has been postulated. In conclusion, novel studies on pathogenesis and biomarkers of silicosis are urgently needed for precise prevention and control of this silently threaten disease of the world. -

Bagassosis, Rare Cause of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: a Case Report

IBEROAMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 04 (2020) 381-384 Journal homepage: www.iberoamericanjm.tk Case Report Bagassosis, rare cause of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: A case report Tyagi Aruna,*, Jadhav Sagara, Waghmare Manoja, Srivastava AKa, Khare ABa aDepartment of Medicine, DVPPF’s Medical College, Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, PIN-414111, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), also called extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a Received 14 May 2020 respiratory syndrome involving the lung parenchyma specifically the alveoli, Received in revised form 18 May terminal bronchioles and alveolar interstitium. HP is caused by delayed allergic 2020 reaction to variety of antigens like microbes, animal proteins, and low-molecular- weight chemicals. Bagassosis is one such HP caused by repetitive inhalation of Accepted 19 May 2020 bagasse. Though use of bagasse as cause of HP is known, use of bagasse in brick- kiln factory as fuel and its association with HP has not been well documented. We Keywords: report a case of HP in a brick-kiln worker where bagasse was used as fuel. Interstitial lung disease A twenty-five years old man, working in a brick kiln for five years, presented with Hypersensitivity pneumonia complaints of dry cough, low grade fever and weight loss for one month. He had Bagassosis bilateral lower lobe crackles on auscultation. The history of bagasse, clay and coal dust exposure, clinical presentation and imaging were suggestive of HP. However, being endemic in India, pulmonary tuberculosis was ruled out by negative Mantoux test, sputum for acid fast bacilli and Cartridge Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test. He was managed with corticosteroids and symptomatic treatment with good response and resolution of clinical signs and radiological changes. -

The Timing of Onset of Symptoms in People with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: a UK General Population-Based Case-Control Study – Supplementary Material

The timing of onset of symptoms in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a UK general population-based case-control study – Supplementary material Thomas Hewson, BMedSci Tricia M McKeever, PhD Jack E Gibson, PhD Vidya Navaratnam, PhD Richard B Hubbard, DM John P Hutchinson, BMBS - Summary of patient population and Consort diagram of numbers of exclusions - Additional tables and figures for cough, consultations for heart failure, consultations for COPD, sensitivity analyses - Read codes for exclusions Summary of patient population Cases Controls n (%) n (%) Sex Male 1,301 (63.1) 4,580 (63.7) Female 761 (36.9) 2,607 (36.3) Age group <55 years 87 (4.2) 277 (3.9) 55-64 years 234 (11.4) 803 (11.2) 65-74 years 638 (30.9) 2,227 (31.0) 75-84 years 803 (38.9) 2,864 (39.9) >84 years 300 (14.6) 1,016 (14.1) Smoking category* Current 348 (18.3) 1,158 (18.2) Ex 810 (42.5) 1,923 (30.3) Never 746 (39.2) 3,269 (51.5) *based on latest record of smoking status prior to diagnosis A Consort diagram of patient selection is shown below. Controls were identified as a 4:1 incidence density sample, matched on age (year of age rather than age-band), sex and GP practice. Each case could have up to four possible controls. Consort diagram of patient selection 13,906 patients from THIN 2,801 cases 11,105 controls 1,415 patients excluded with inadequate length of data pre-diagnosis (already applied to cases 12,491 patients when selected) 2,801 cases 9,690 controls 96 patients excluded aged 40 or below 12,395 patients 2,774 cases 9,621 controls 153 cases excluded -

Evidence Process for Cough/Dyspnea Guideline Research 03/12/2019 Guideline Review Using AGREE II Instrument – 03/12/2019

© CDI Quality Institute, 2019 Evidence Process for Cough/Dyspnea Guideline Research 03/12/2019 Guideline Review using AGREE II instrument – 03/12/2019 Approximately 44 Potentially relevant guidelines identified in various resources* Approximately 19 25 Guidelines Excluded Selected for inclusion Exclusion Criteria: Non-English language Pediatrics Age of Publication Ex-U.S. focus Little or no discussion of advanced imaging 2 Consensus/Practice-based 23 Evidence-based Guidelines Guidelines evaluated using AGREE II 19 4 Guidelines meeting AGREE II inclusion Guidelines not meeting AGREE II inclusion threshold of combined total score ≥ 90 threshold of combined total score ≥ 90 AND Rigor of Development Scaled Domain AND Rigor of Development Scaled Domain Score Percentage > 50% Score Percentage > 50% *Information Resources: Ovid Medline, NCBI PubMed, National Guideline Clearinghouse, Guidelines International Network, TRIP Database, Choosing Wisely, Cochrane Database, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and numerous specialty society websites Additional Internet and bibliographic searches were performed for all phases of research For use only in connection with development of AUC by the CDI Quality Institute’s Multidisciplinary Committee © CDI Quality Institute, 2019 Evidence Process for Cough/Dyspnea Research 03/12/2019 Systematic Literature Research – Ovid Medline Database Combined Evidence Tables References 18 Observational Studies 0 Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 0 Physician reviews *Note: due to overlapping search results, a -

Airborne Dust WHO/SDE/OEH/99.14 Chapter 1 - Dust: Definitions and Concepts

Hazard Prevention and Control in the Work Environment: Airborne Dust WHO/SDE/OEH/99.14 Chapter 1 - Dust: Definitions and Concepts Airborne contaminants occur in the gaseous form (gases and vapours) or as aerosols. In scientific terminology, an aerosol is defined as a system of particles suspended in a gaseous medium, usually air in the context of occupational hygiene, is usually air. Aerosols may exist in the form of airborne dusts, sprays, mists, smokes and fumes. In the occupational setting, all these forms may be important because they relate to a wide range of occupational diseases. Airborne dusts are of particular concern because they are well known to be associated with classical widespread occupational lung diseases such as the pneumoconioses, as well as with systemic intoxications such as lead poisoning, especially at higher levels of exposure. But, in the modern era, there is also increasing interest in other dust-related diseases, such as cancer, asthma, allergic alveolitis, and irritation, as well as a whole range of non-respiratory illnesses, which may occur at much lower exposure levels. This document aims to help reduce the risk of these diseases by aiding better control of dust in the work environment. The first and fundamental step in the control of hazards is their recognition. The systematic approach to recognition is described in Chapter 4. But recognition requires a clear understanding of the nature, origin, mechanisms of generation and release and sources of the particles, as well as knowledge on the conditions of exposure and possible associated ill effects. This is essential to establish priorities for action and to select appropriate control strategies. -

Interstitial Lung Disease, Occupational

Occupational Airways A newsletter of the Occupational Health & Special Projects Program, Division of Environmental Epidemiology and Occupational Health (EEOH), Connecticut Department of Public Health, 410 Capitol Avenue, MS# 11OSP, P.O. Box 340308, Hartford, CT 06134-0308 (860) 509-7744 Vol. 3 No. 3 December 1997 microorganisms, serum proteins and chemicals. This issue: Table 1 includes a number of entities and offending Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP) allergens more likely to be seen in Connecticut. Not as common in Connecticut but well described Some Clinical Observations about in the literature are bagassosis in sugar cane Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) in CT workers, sisal worker’s disease, maple bark stripper’s disease, wheat weevil’s disease and malt Summary Table of Reported Cases worker’s lung. of Selected Respiratory Diseases in CT 2. Symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of HYPERSENSITIVITY breath The symptoms occur in a spectrum, from PNEUMONITIS (HP) acute through chronic stages. Two-thirds develop By Donald C. Kent, MD FACP, FCCP, FACOEM chills, fever, cough and shortness of breath within Consultant, Electric Boat Division, Groton, CT; four to eight hours after exposure, which develop Consultant, Occupational Health Center, Pequot Health Center into symptoms of malaise, myalgia Lawrence & Memorial Hospital, Groton, CT; and headache. Initial symptoms Consultant, Pfizer Central Research, Groton ,CT usually subside within hours. The Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), also called sub-acute phase is represented by a extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a granulomatous decrease in the acute symptoms but progressive interstitial lung disorder resulting from reaction to increase in shortness of breath. The chronic phase repeated inhalations of and sensitization to is characterized by progressive shortness of allergens in a predisposed host.1 Occupationally, it breath, and with features of both an interstitial and occurs in susceptible workers, and is an airways obstruction disorder. -

Silicosis: Biomarkers and Pathogenesis

Journal of Lung, Pulmonary & Respiratory Research Research Article Open Access Silicosis: biomarkers and pathogenesis Abstract Volume 5 Issue 5 - 2018 Ramazzini first described this disease, namely “ Pneumonoultra-microscopicsili- Attapon Cheepsattayakorn,1,2 Ruangrong covolcanokoniosis” and then was changed according to the types of exposed dust. No 3 reliable figures on the silica-inhalation exposed individuals is officially documented. Cheepsattayakorn 110th Zonal Tuberculosis and Chest Disease Center, Thailand How silica particles stimulate pulmonary response and the exact pathophysiology of 2Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, silicosis are still not known and urgently require further research. Nevertheless, many Thailand researchers hypothesized that pulmonary alveolar macrophages play a major role by 3Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai secreting fibroblast-stimulating factor and re-ingesting these ingested silica particles University, Thailand by the pulmonary alveolar macrophage with progressive magnification. Finally, ending up of the death of the pulmonary alveolar macrophages and the development Correspondence: Attapon Cheepsattayakorn, 10th Zonal of pulmonary fibrosis appear. A hypothesis of silicosis-associated abnormal Tuberculosis and Chest Disease Center, 143 Sridornchai Road, immunoglobulins has been postulated. In conclusion, novel studies on pathogenesis Changklan Muang, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand, Tel 66 53 276364, and biomarkers of silicosis are urgently needed for precise -

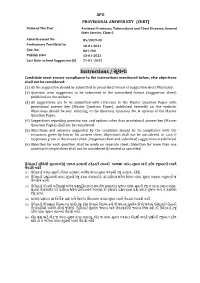

Instructions / સૂચના Candidate Must Ensure Compliance to the Instructions Mentioned Below, Else Objections Shall Not Be Considered:

APO PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY [CBRT] Name of The Post Assistant Professor, Tuberculosis and Chest Diseases, General State Service, Class-1 Advertisement No 85/2019-20 Preliminary Test Held On 10-01-2021 Que. No. 001-200 Publish Date 13-01-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion (S) 21-01 -2021 Instructions / સૂચના Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted in prescribed format of suggestion sheet Physically. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed formatr (Suggestion rSheet) published on the website.r r (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Maste Question Pape withr provisional answe key (Maste Question Paper), published herewith on the website. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, rQuestion No. & options ofr the Maste Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options othe than provisional answe key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. r (5) Objections and answers suggestedr by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses givenr by him in his answe sheet. Objections shall not be considered, r in case, if responses given in the answe sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection fo each question shall be made on separate sheet. Objection fo more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered & treated as cancelled. ઉમેદવાર ે નીચેની સૂચનાઓનું પાલન કરવાની તકેદારી રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા-સૂચન અંગે કર ેલ રજૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહીં (1) ઉમેદવારે વાંધા-સૂચનો િનયત કરવામાં આવેલ વાંધા-સૂચન પકથી રજૂ કરવાના રહેશે. -

USMLE® Content Outline

USMLE® Content Outline A Joint Program of the Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc., and the National Board of Medical Examiners® This outline provides a common organization of content across all USMLE examinations. Each Step exam will emphasize certain parts of the outline, and no single examination will include questions on all topics in the outline. The examples listed within the outline are just examples. Questions may include diseases, symptoms, etc., that are not included in the outline. The USMLE program continually reviews its examinations to ensure their content is relevant to the practice of medicine. As practice guidelines evolve or are introduced, the content on USMLE is reviewed and modified as needed. At times, there is a change in emphasis on new content development that arises from our ongoing peer-review processes. For example, there has been an emphasis on new content developed assessing competencies related to geriatric medicine, and prescription drug use and abuse. USMLE has also focused recent efforts on the often unrecognized health care needs of recently returning servicemen and servicewomen (eg, traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder), and the families of deployed servicemen and servicewomen. While many of the medical issues related to the health care of these special populations are not unique, certain medical illnesses or conditions are either more prevalent, have a different presentation, or are managed differently. Knowledge of foundational science and clinical science in these content areas will be assessed on the USMLE Step 1, Step 2 CK, and Step 3 examinations. Examinees should refer to the test specifications for each examination for more information about which parts of the outline will be emphasized in the examination for which they are preparing. -

932 Chest Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes

Medical Policy Chest Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes Policy Number: 932 BCBSA Reference Number: N/A NCD/LCD: N/A Related Policies • Medicare Advantage: Advanced Imaging/Radiology and Sleep Disorder Management Clinical and Utilization Guidance Redirect, #923 • Advanced Imaging/Radiology CPT and HCPCS Codes, #900 • Advanced Imaging/Radiology, #968 • Oncologic Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #929 • Abdomen and Pelvic Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #930 • Brain Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #931 • Extremity Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #933 • Head and Neck Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #934 • Spine Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #935 • Vascular Imaging CPT, HCPCS and Diagnoses Codes, #936 Table of Contents Commercial Products .................................................................................................................................... 1 Medicare Advantage Products ...................................................................................................................... 1 CPT Codes / HCPCS Codes / ICD Codes .................................................................................................... 2 CPT Codes: 71250, 71260, 71270 Chest CT ............................................................................................... 2 CPT Codes: 71550, 71551, 71552 MRI chest ............................................................................................ 21 CPT Codes: 78811, 78812, 78813, 78814, 78815, 78816 PET imaging ..................................................