THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA a Model for Integrating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

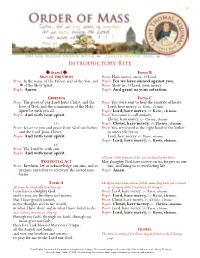

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

What Is “Ad Orientem”? Why Is the Priest Celebrating with His When We All Celebrate Facing East, the Us to God

What is “Ad Orientem”? Why is the priest celebrating with his When we all celebrate facing East, the us to God. Look where he’s pointing, not back to us? He isn’t. He could only ‘have priest is part of the people, not separated at the one pointing. his back to us’, if we were the center of from them. He is their leader and Facing East reinforces the mystery his attention at Mass. But we aren’t, God representative before God and we are of the Mass. We have become so is. The priest is celebrating looking east, all one, together in our posture. Think familiar with the actions of the priest; in anticipation of the coming of Jesus. about all those battle we sometimes forget Remember the words of the Advent images of generals the great mystery at the hymn, People Look East? “People, look on horseback—they heart of it: that the priest East. The time is near of the crowning of are facing with their exercises his priesthood the year. Make your house fair as you are troops, not facing in Jesus Himself and it able, trim the hearth and set the table. against them. Just so, is Jesus really and truly People, look East and sing today: Love, the priest is visibly present both standing as the guest, is on the way.” part of the people and the priest and on the altar We have become so familiar to Mass clearly acts in persona as the sacrifice. When celebrated with the priest facing us that Christi capitis, “in the the priest bends low over we have forgotten that this is a relatively person of Christ the the elements and then new innovation both historically and head,” when we all face elevates, first the host and liturgically and actually something that the same direction. -

SAINT BASIL the GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of An

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of an Altar Server O God, You have graciously called me to serve You upon Your altar. Grant me the graces that I need to serve You faithfully and wholeheartedly. Grant too that while serving You, may I follow the example of St. Tarcisius, who died protecting the Eucharist, and walk the same path that led him to Heaven. St. Tarcisius, pray for me and for all servers. ALTAR SERVER'S PRAYER Loving Father, Creator of the universe, You call Your people to worship, to be with You and each other at Mass. Help me, for You have called me also. Keep me prayerful and alert. Help me to help others in prayer. Thank you for the trust You've placed in me. Keep me true to that trust. I make my prayer in Jesus' name, who is with us in the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1 PLEASE SIGN AND RETURN THIS TOP SHEET IMMEDIATELY To the Parent/ Guardian of ______________________________(server): Thank you for supporting your child in volunteering for this very important job as an Altar Server. Being an Altar Server is a great honor – and a responsibility. Servers are responsible for: a) knowing when they are scheduled to serve, and b) finding their own coverage if they cannot attend. (email can help) The schedule is emailed out, prior to when it begins. The schedule is available on the Church website, and published the week before in the Church Bulletin. We have attached the, “St. Basil Altar Server Manual.” After your child attends the two server training sessions, he/she will most likely still feel unsure about the job – that’s OK. -

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2002 Volume 129 No.4

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2002 Volume 129 No.4 -~..~ " 1 ......... -- Cathedral and Campanile, Florence, Italy. SACRED MUSIC Volume 129, Number 4, Winter 2002 EDITORIAL 3 Kneeling for Holy Communion SIR RICHARD TERRY AND THE WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL TRADITION 5 Leonardo J. Gajardo "ONE, HOLY, CATHOLIC AND APOSTOLIC?" 9 Joseph H. Foegen, Ph.D. NARROWING THE FACTUAL BASES OF THE AD ORIENTEM POSITION 13 Fr. Timothy Johnson KNEELING FOR COMMUNION IN AMERICA?-YES! 20 Two letters from Rome REVIEWS 22 OPEN FORUM 25 NEWS 25 CONTRIBUTORS 27 INDEX 28 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 134 Christendom Drive, Front Royal, VA 22630-5103. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistant: Christine Collins News: Kurt Poterack Music for Review: Calvert Shenk, Sacred Heart Major Seminary, 2701 West Chicago Blvd., Detroit, MI 48206 Susan Treacy, Dept. of Music, Franciscan University, Steubenville, OH 43952-6701 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 5389 22nd Ave. SW, Naples, FL 34116 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Father Robert Skeris Vice-President Father Robert Pasley General Secretary Rosemary Reninger Treasurer Ralph Stewart Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Stephen Becker Father Robert Pasley Kurt Poterack Rosemary Reninger Paul F. Salumunovich Rev. Robert A. Skeris Brian Franck Susan Treacy Calvert Shenk Monsignor Richard Schuler Ralph Stewart Membership in the Church Music Association of America includes a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at Least 30 Minutes Prior to the Start of Mass

MC Checklist for the Historic Church October 2013 Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to the start of Mass. • Take down the chain across the parking lot. • Unlock door of church. • Turn on interior lights and any appropriate exterior lights. • For a weekend Mass check the MC/Greeter/Usher notes (found on the Offertory table - cabinet behind pews on the left side of aisle) for any updates or changes for that Mass. • Turn the sound system on (located in the wooden cabinet in the Adoration Room). The button on the right of each box needs to be pushed in. You will know if they are both on if they turn green. Note that the button on the smaller device on top has to be pushed in for a few seconds before it turns green. • To check if they are both on properly see if the green light is on by the bottom of the microphone on the ambo. Lectionary • Turn on the fans if necessary. The switches for the fan are located in the same cabinet as the sound system. The switch to the left controls the speed of the fan. Fan Placard • Turn the altar and sanctuary lights on (switches are labeled inside the Adoration Room). • Turn the thermostat (by the sacristy door) up to 68 degrees. • For weekend Masses check the Presider’s Schedule to see who is celebrating (taped to the small refrigerator in the sacristy). If Fr. Frazier is not presiding or not has not yet arrived, get the appropriate vestments from the Parish Center and hang on the back of the door of Sacristy. -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The Work of Borghesi Is a Wonderful Contribution to Understanding the Thinking and Person of Pope Francis and to Receiving An

“The work of Borghesi is a wonderful contribution to understanding the thinking and person of Pope Francis and to receiving and implementing his magisterium at a time of change in the Church and the world. It is my sincere hope that bishops, priests, seminary professors, lay theologians, and leaders will profit greatly from this text as they carry out the important work of the New Evangelization.” —Archbishop Christophe Pierre Apostolic Nuncio to the United States “Massimo Borghesi has provided an indispensable resource for all who want to understand why Pope Francis thinks the way he does. Both erudite and scholarly, The Mind of Pope Francis reveals the intellectual and cultural formation of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, with the added benefit of recently recorded and highly reflective interviews with the subject himself. Beautifully translated, this is a vital addition to the anthology of books on this most captivating and consequential religious leader.” — Kerry Alys Robinson Global Ambassador, Leadership Roundtable “Massimo Borghesi’s book is the first real intellectual biography of Jorge Mario Bergoglio and it builds a bridge between the different universes of today’s global Catholicism: different generations of Catholics; different areas of the world; different theological, philosophical, and socio-political backgrounds. This book is an invaluable contribution for the comprehension of this pontificate and potentially a game-changer for the reception of Pope Francis, especially in the English-speaking world.” — Massimo Faggioli Professor of Historical Theology, Villanova University “Pope Francis’ predecessor was an internationally renowned theologian. Perhaps because of that, many have dismissed the Argentinian pope as lacking in intellectual ‘heft.’ Massimo Borghesi’s fascinating and informative study of the intellectual influences on Pope Francis has exploded that canard, demonstrating the intellectual breadth, subtlety and perspicacity of Francis’ thought. -

The Roman Missal: the Order of Mass — a Guide for Composers

The Roman Missal The Order of Mass — A Guide for Composers DRAFT TEXT This document is being prepared to support the eventual publication of the English and Welsh edition of the Roman Missal 3rd edition. It will not be finalised until the English translation has received approval. At that the approved texts for the Order of Mass will be inserted together with any further information about the provision of music in the new edition. Until that time this document is offered for comment and as an indication of future guidance. Introduction The publication of the third edition of the Missale Romanum in 2002 and the subsequent translation into the vernacular offers an opportunity to both evaluate current musical settings for the Mass and provide guidance to composers in the future. This guide for composers highlights the provision for music in the Order of Mass in the Roman Missal. It brings together the core texts of the liturgy for musical setting as a reference and recommends best practice. This guide does not cover: the rites of Liturgical Year, celebrations of Sacraments and Funerals or the provision of hymns though many of the principles described will apply. This document is arranged in two parts. The Introduction is divided into sections on the Ministry of the Composer and general principles about the setting of liturgical texts and music for the liturgy. The second part is a description of the Order of Mass with details of both the liturgical and musical issues affecting each part. The Ministry of the Composer Composers, filled with the Christian spirit, should feel that their vocation is to develop sacred music and increase its store of treasures. -

Dialogue Mass

DIALOGUE MASS Rev Edward Black As must surely be the case with many readers of The Remnant, I have followed the series of articles on the Dialogue Mass under the title ”Debating The Relevant Issues” with increasing bemusement. In what sense is the question of the Dialogue Mass relevant to us and where is this debate going? The extremely detailed article of Mr Tofari was certainly reminiscent of the content and style of the liturgical reformers of the 1950s and it is not surprising that it should have evinced the alarmed response of Mr Dahl. Are there really any traditional Catholics ready to repeat the painful experiences of 50 years ago? Mr Tofari’s article seems to indicate that he, at least, is one. Although he rightly states that Dialogue Mass is not a matter of doctrine but of praxis, he nevertheless also states that it is an important question. Indeed it is. Silence and sound are mutually exclusive. If his assertion is ever conceded in practice that a single person who decides to avail himself of making the responses at Mass has every right to do so then it spells the final end of what was once the universal and exclusive practice of the Western Church for more than 1000 years. Although this is an important matter, it is likewise a tiresome one — for it seems that every traditional institution and practice must be permanently placed in a position of self — defence and called upon at any time to justify itself. The standard procedure of the liturgical reformers has always been to appeal to the practice of the early Church, ignoring the greater part of her history until the 20th century, (save for the purposes of ridiculing it), in order to justify their innovations.